Seventy precise years separate the first modern monographic exhibition on Luca Signorelli, the one held in 1953 first in Cortona and then in Florence at Palazzo Strozzi, from the more recent one, namely the one organized this year for the 500th anniversary of the painter’s death, curated by Tom Henry and entitled Signorelli 500. Maestro Luca da Cortona, painter of light and poetry. Curiously, the two exhibitions share the same venue, the Museo dell’Accademia Etrusca in Cortona, but the similarities can be said to have ended here. The 1953 exhibition had a pioneering character, counting on about eighty works, many of them from Signorelli’s workshop, and above all it was torn apart by the jaws of a mostly adverse criticism, so much so that in the end, a case of extreme rarity for a first monographic exhibition, the figure of Luca Signorelli came out strongly diminished. The reviews were angry both with the exhibition (and with the president of the scientific committee, Mario Salmi: at the time the term “curator” was not used) and with the artist: Roberto Salvini wrote that Signorelli was to be blamed for “an insufficient awareness of the fantastic essence of art, an ill-considered distinction of the limits between art and artisan practice,” and even defined him as a painter who “always lived in the closed confines of the province,” who frequented Florence but not to the point of absorbing “that open and metropolitan culture,” endowed with a humanistic spirit that, however, “did not translate into mental clarity about the rights of the imagination.” He was, in short, little more than a “medieval craftsman.” Alberto Martini, Longhi’s very young student, then 22 years old (he would die prematurely at the age of 34 in a car accident), spoke of an artist “all sense and physicality,” whose characters were “so many giants in reinforced concrete,” built with an “exuberant plasticity obtained by means of an arid chiaroscuro.” Castelnovo and Ragghianti were more concerned with demolishing the exhibition, going so far as to question whether it had been an appropriate operation. Among the few to express appreciation instead were Luisa Becherucci in Rivista d’Arte (for her, Signorelli was an artist strong in a “real sense of life” that “could yield nothing of its actuality to express instead the ideal catharsis, the extreme landing place of Florentine idealism,” and who “could not conceive of the soul without the reality of its corporeal envelope”) and, in Emporium, Renzo Chiarelli, according to whom the exhibition imposed itself as a “model of seriousness, sobriety and decorum.”

It took time for Luca Signorelli’s profile, which had been navigating through alternating critical fortunes even before that exhibition, to rise from the rubble of 1953. It took time to clarify the contours of his figure, which we now recognize as among the most significant and original of his period because of the tension, both physical and emotional, and the energetic vigor of his figures that anticipate Michelangelo, because of his nudes innervated by the study of theantiquity (Vasari already noted this, by the way), for his dramatic impetus, for his admirable compositional talent (noted with conviction by Pietro Scarpellini, according to whom Signorelli succeeded “in overcoming scenographic assumptions with such ingenious as to turn artifice into truth and oratory into poetry”), for that “pilgrim spirit,” as Giovanni Santi called him, which enabled him to bring together his pronounced sense of realism and the study of theantique in paintings in which we witness that “harmonious fusion of classical and Christian civilization” that Tiziana Biganti identified in the cycle of the chapel of San Brizio in Orvieto, but which is actually found in so many other works by the Cortona artist. Signorelli is, in essence, a modern artist, animated by modern instances, driven by a tragic force that is all of his time and that floods late 15th-century Tuscan art with fragrant novelty. To have full knowledge of the disruptive scope of Luca Signorelli’s art, studies, scholarly articles, books and other exhibitions were needed: the first complete reconstruction of his figure after the 1953 exhibition dates back to the exhibition held in 2012 in Perugia, Orvieto and Città di Castello: curated by Fabio De Chirico, Vittoria Garibaldi, Tom Henry and Francesco Federico Mancini, it gathered almost everything that could be collected, comparing Signorelli’s works with those of the artists of his time, also displaying a fair number of drawings (which are instead absent from this year’s exhibition, by Henry’s precise choice) and thus returning an exhaustive overview of the artist. Then, in 2019, it was the turn of the Capitoline Museums’ small focus on Signorelli’s relationship with antiquity. And finally we come to the 2023 exhibition.

It could be considered a finishing exhibition, so to speak. An exhibition that brings to the public less than thirty works, but counting on a very high density of masterpieces: there are only certain works by Signorelli, or referable to him with a high margin of certainty, there are many fundamental works, the entire chronological span of his career is covered. Just the portion that precedes Signorelli’s commitment to the Sistine Chapel in 1481-1482 is missing, but the gap is due to the fact that there are still no early works that agree with everyone (clarifying the matter in the terms due is Laurence Kanter in his catalog essay), not to mention that the 2012 exhibition already included a copious section on the young Signorelli, and since then there have been no new works so shocking as to require a new examination of a subject complex to study and handle. Henry then admits two further shortcomings, namely the already noted absence of drawings and the lack of a documentary apparatus: here, too, it is the catalog that makes up for it. The main reason for the exhibition is thus to reiterate Signorelli’s importance: and that importance, Henry writes, lies in his “great qualities as a colorist, sculptural painter and highly personal iconographer,” as well as in the merit of having surpassed his contemporaries with the overwhelming power of the Orvieto frescoes and the later works, which made him “a beacon for the generation that followed.”

Installations of

Installations of Set-ups of the exhibition

Set-ups of the exhibition Set-ups of the exhibition

Set-ups of the exhibition Set-ups of the

Set-ups of theThe tour is spread over two rooms, and the result is therefore a decidedly compressed layout, even too much: works in the corners, dividing panels on which some works are hung, cramped spaces, only one seat (not least because it is difficult to imagine points where to place others). In the organizers’ defense is the fact that the MAEC is a difficult museum for exhibitions with quantities of works on display similar to that of the review on Signorelli, and the fact that, in the general absence of events dedicated to the painter in the year of the 500th anniversary (of note only the remounting of the Signorelli Room at the nearby Diocesan Museum: a visit, of course, is a must), the museum wished to honor the artist with an exhibition that may not count on the best layout in history, but certainly leaves itself to be appreciated, notably for the specific weight of the nucleus that Henry was able to assemble, truly able to offer a good summary of Luca Signorelli’s qualities. Useful then to point out the organizers’ rare gesture of courtesy toward the public: a copy of the excellent catalog, published by Skira, left for free consultation where it is needed, that is, in front of the works.

The itinerary among Signorelli’s works brought to the MAEC proceeds in chronological order, with the sole exception of the VolterraAnnunciation, which is presented in the second room for obvious reasons of space conformation. As mentioned, all of Signorelli’s work prior to the Sistine Chapel frescoes is missing: we begin, therefore, with a work that arrives on loan from France, the Madonna and Child, St. John the Baptist and a Saint, a rare centered work, definitively assigned in 1999 to Signorelli by Henry himself: it bears traces of the Verrocchio style that suggest that it was executed in the mid-1980s, probably in Florence. It is a work about which very little is known: far better known, on the other hand, is the story of Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee (formerly part of the predella of the Bichi Altarpiece that was in the church of Sant’Agostino in Siena), which MAEC audiences will find on the wall opposite that of the Madonna that opens the exhibition. In contrast to the Madonna in the Fondation Jacquemart-André, it is a superb work, highly praised since the nineteenth century, which is distinguished by the variety of its attitudes, the vitalism of its characters, and the vein of restlessness that animates them (Henry, in the two characters on the far left, comes to see an anticipation of Pontormo).

We return to admire the works on the opposite wall: the room ends with three tondi that Signorelli painted in the early 1590s. Returning to Italy after the 2019 exhibition is the tondo from the Musée Jacquemart-André, the most bizarre of the three, especially because of the presence of the elderly man on the right who is still not identified with certainty: perhaps a shepherd, but more likely to be St. Jerome, since he has all the iconographic attributes typical of the saint (the emaciated appearance, the threadbare robes, the hand at his chest that would seem to conceal, although it is poorly seen, a stone: the most pointed comparison is with the Saint Jerome of Piero della Francesca’s Montefeltro Altarpiece), while decidedly less fitting are other identifications (a similar roundel with the figure of a shepherd, an elderly one at that, would be very rare). He does not have a halo, just as St. Giovannino does not, and there are, in any case, attested works by Signorelli in which the saints appear without such an attribute (also at the exhibition: see the Farsetti tondo in the second room). The presence of the Jacquemart-André tondo offers the possibility of comparing the Madonna painted here by Luca Signorelli with that of theAnnunciation in Volterra: it is identical, a useful detail for understanding working methods in the Cortona artist’s workshop. And very similar is also the Virgin of the tondo in Palazzo Pitti, the one with the Holy Family and St. Barbara, also a work likely painted for a Florentine patron, while differing from the other two tondi, perhaps preceding them chronologically, is the Corsini tondo, a panel from the early 1890s, which for its attitudes, for its harshness of sign combined with more delicate (the Virgin’s face and neckline) and for the almost expressionist vein that sustains it, recalls in some ways a masterpiece such as the St. Onofrio Altarpiece painted in 1484 for Perugia Cathedral.

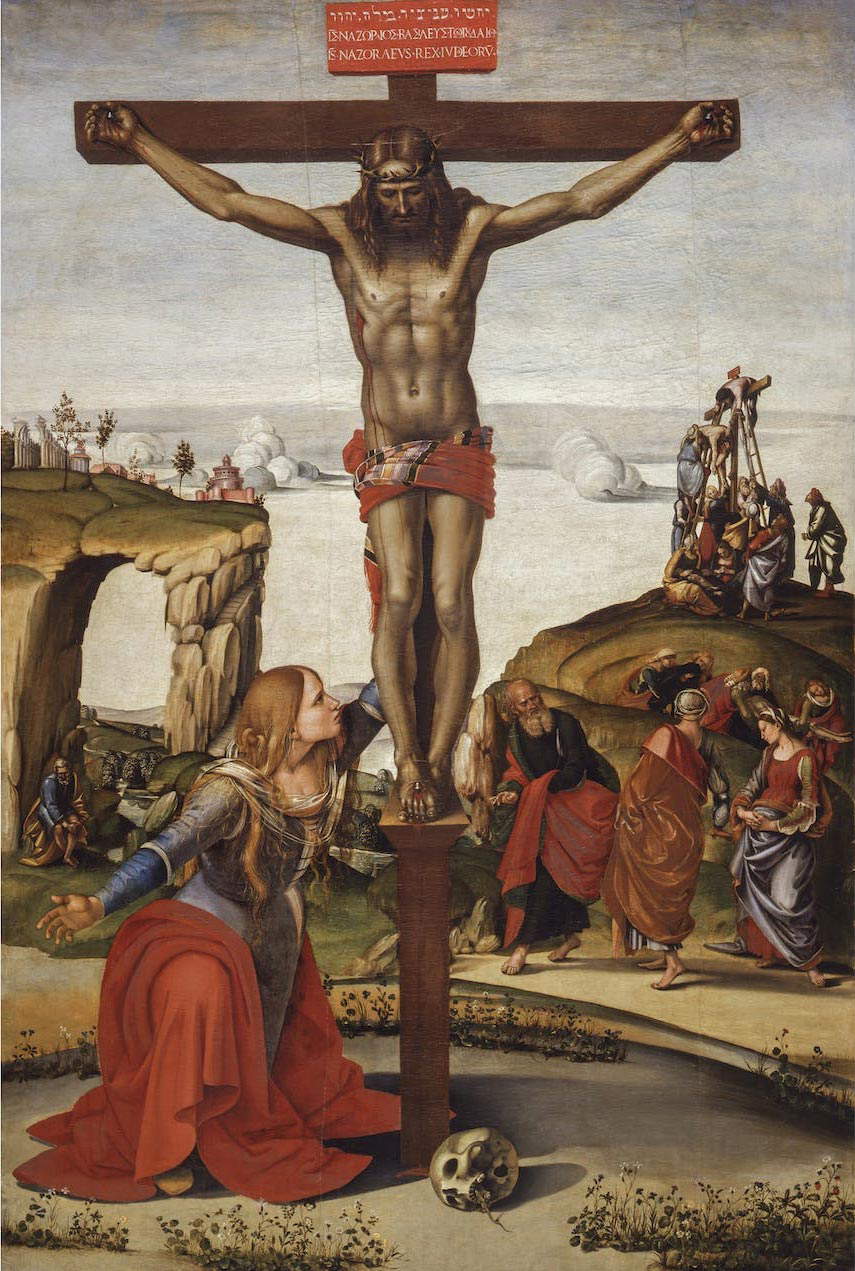

Surprising is the sequence that opens the second room: the visitor finds in succession, one after the other, theAnnunciation of Volterra, the Stendardo of Sansepolcro on the opposite wall, and the Crucifixion of Annalena, arranged next to theAnnunciation and placed in dialogue with the stendardo, which on the recto presents the same iconographic subject (on the verso, on the other hand, one observes an intense depiction of Saints Anthony and Eligius intent on reading, and in turn in dialogue with the Magdalene of Orvieto, which is found further ahead in the continuation of the itinerary). The possibility of seeing the three works together is one of the novelties of the exhibition, since never before has such a comparison been offered to the public: the innovative, resplendent, and seductive Annunciation, which at every glance invites one to linger on a new detail (the dazzling marble floors, the dusky sky streaked with orange, the appearance of the Eternal Father in a mandorla of sculptural cherubs, the completely new absolute of the sculpture of King David above the Virgin, the very clear spatial division with the archangel on the outside and the Madonna on the inside, the fluttering of the veils, Mary’s book that out of amazement has fallen to the ground still open), the Uffizi Crucifixion with one of the most bewitching Magdalenes of this end of the fifteenth century and with the almost surrealist rocks behind the cross, and then the later processional banner of Sansepolcro, charged with emotional tension, with the anachronistic but effective insertion of the figure of St. Anthony Abbot to fulfill a request of the commission, and with the singular detail of the face painted in the clouds on the left. Three works that, in themselves, and given also the possibility of admiring them together for the first time, are worth admission to the MAEC exhibition. Signorelli’s taste for the antique then surfaces in the Nativity from the Capodimonte Museum, with the sculptural and almost monumental profiles of the protagonists, and with the hut that takes on the appearance of a classical temple. On display alongside is the Madonna and Child that once formed the altarpiece of the oratory of the Confraternity of the Virgin Mary of the Black Robe of Montepulciano, preserved today in the Museo Civico of the city of Pistoia, and on display exceptionally reunited with its predella, which is now in the Uffizi instead and is an extraordinary episode of liveliness, refinement, and narrative taste.

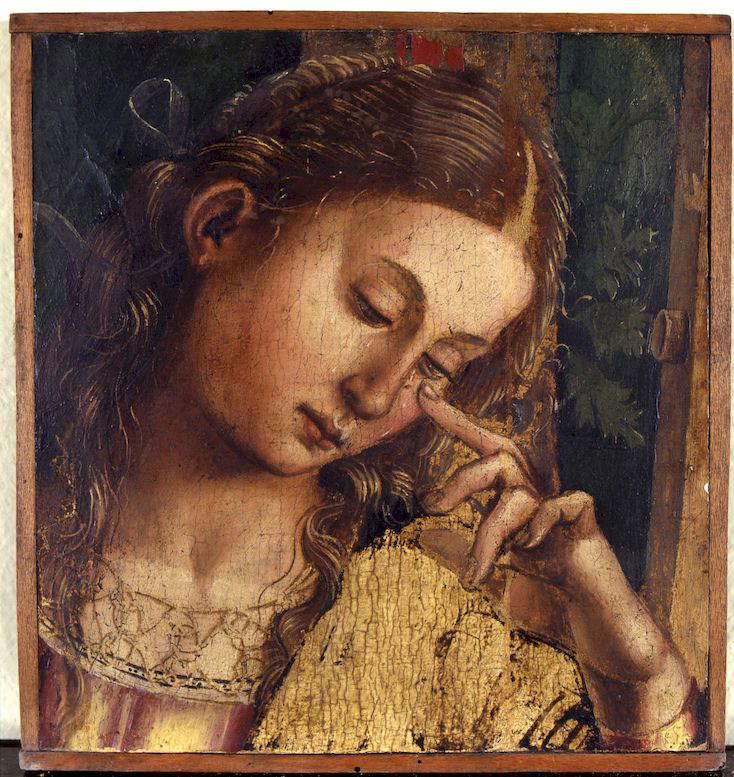

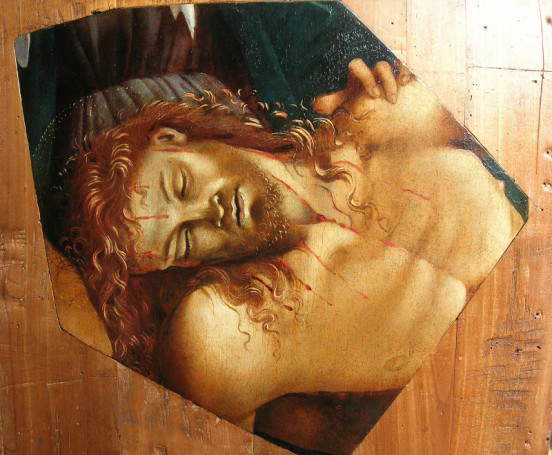

Among the main merits of the Cortona exhibition is also counting the reuniting of the fragments of the Matelica Altarpiece, a Lamentation painted in Cortona (and then sent to the Marche city: it was intended for the high altar of the church of Sant’Agostino) between 1504 and 1505, paid for with the considerable sum of 105 florins (thanks to which the artist was able to buy two houses in his city), given in 1736 by the friars of Sant’Agostino to a citizen of Matelica in exchange for a contribution to restore the church, and then dismembered between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we do not know when exactly or by whom. The surviving fragments today are divided among several collections: two are held in as many private collections, one is at the National Gallery in London, and the remaining two are in Bologna (both can be seen at the Palazzo d’Accursio, but while the weeping Pia donna is owned by the Collezioni Comunali d’Arte, the Head of Christ is owned by Unicredit). The public thus has a chance to see the fragments side by side (along with a panel showing the possible reconstruction), appreciating the quality of a work that figures among the pinnacles of Signorelli’s production in the early part of the sixteenth century, and keeping in mind that, according to Henry, it is credible to think that other fragments may emerge in the future, including a Resurrection last attested in the 1950s at a dealer and then never reappeared. Next to the five fragments, here is then on display a tondo from the same period and perhaps painted for the same patron as the Matelica altarpiece, that with the Madonna and Child and Three Saints: original, for a painting of this kind (despite the qualitative gap in the figures of the two side saints suggesting the intervention of a different hand than that of the master), is the invention of the saint in the center (in good probability it is Saint Bernard of Clairvaux) who is interrupted from the reading by the apparition of the Madonna and Child.

On the adjoining wall is an important loan from the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Orvieto, namely the Saint Mary Magdalene that was formerly in Orvieto Cathedral, commissioned from the artist probably as a result of the frescoes in the chapel of San Brizio: it is a painting that introduces some novelties in Signorelli’s art, in particular the decorative richness that is especially appreciated in the rich drapery. If the Magdalene is a work of traditional layout that finds radiant expressiveness in its vivid decorativism, all animated by fully contemporary solicitations is the disruptive Communion of the Apostles, a masterpiece of 1512 and the only painting that arrives on loan from the Diocesan Museum of Cortona. A rare painting in terms of its iconographic subject matter, for which Signorelli may have drawn inspiration from a counterpart work by Justus of Ghent (the Corpus Christi Altarpiece, now in the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, and which Signorelli may have had the opportunity to see in the city in the Marche), it draws inspiration for its setting from Perugino, because of the way the scenes are placed under a Classical portico foreshortened in depth and open to a clear sky, as seen in the Pietà painted for the church of the convent of San Giusto alle Mura in Florence, and now in the Uffizi (Signorelli chooses, however, unlike Perugino, to decorate the columns with elegant grotesques, and to insert signature and date in the capitals of the first two). Adolfo Venturi, in his 1921 monograph, grasped all the novelty of the scene: “the traditional apparatus is dispelled by the stroke that suddenly breaks the thread of iconographic custom: the nave of a temple open to the whitening sky (Perugian background), welcomes the very human Christ, the priest advancing at a slow pace, distributing the sacred Bread to the faithful. Two hairy heads of apostles, curved equally on the shoulder, form open wings to the absorbed figure of God; and with sudden divergence of wings the ranks of the other apostles open away in the space of the nave, arranged in double order, with magnificent compositional unity.” Signorelli’s great modernity is also grasped in the whirlwind of emotions that animates the apostles, an element of a sensibility that could almost be called Leonardesque: if among the apostles standing at Christ’s right hand the dominant feeling is that of pious devotion (bordering on tragic intonations, if we observe their expressions, accentuated by Signorelli’s typical nervous lines), so much so that we see them all kneeling waiting to receive thehost, to his left the grim figure of Judas, intent on surreptitiously concealing his hand in his purse, instead triggers, who knows how consciously, mixed reactions, worried looks (note St. Peter’s eyes), heated discussions.

Arriving on loan from the High Museum in Atlanta are the two tablets with the Stories of St. Nicholas, another fine novelty since never before have these two fragments, once part of the predella of the opisthograph altarpiece of the Lamentation that still stands in the church of San Niccolò in Cortona, and which together with the altarpiece in the church of San Domenico is what still remains of Signorelli’s work in the city’s houses of worship: Significant, then, that the return of the two panels to Cortona takes place on the occasion of the five-hundredth anniversary exhibition. These are works that denote an accentuation of Signorelli’s forward letter expressionism toward the years of his late maturity: this can also be seen in the Flagellation, on loan from the Ca’ d’Oro in Venice, displayed not far away, a work with “exaggerated and even disconcerting illumination [...] intended to create a sense of drama and tension” (thus Henry). And there is much Cortona in the exhibition’s closing lines as well: integral to the itinerary are the two works in the MAEC’s collection, namely theAdoration of the Shepherds of c. 1509-1513, perhaps not among Signorelli’s best (so much so that the complete authorship has been questioned, though confirmed by Henry and Kanter), and the far more interesting tondo with the Madonna and Child and Saints Michael, Vincent, Margaret of Cortona and Mark, which strikes every visitor for its extravagant and tortuous depiction of the devil under the imperious figure of St. Michael, and especially for the realistic model of the city of Cortona in the hands of St. Mark, stunning in its highly original orographic accuracy: it will be surprising, for the visitor who has arrived in the center from the hamlet of Camucia, to see the superimposibility of ancient Cortona with that of the present day, which has preserved its face, conformation, and buildings. The conclusion is entrusted to the Presentation at the Temple from a private collection, which can be placed in the extreme stages of Signorelli’s career, and which was already on display at the 2012 exhibition, and which should be kept in mind when visiting the Diocesan Museum, since the institute preserves an almost identical version. Finally, there is an appendix in the adjoining room, the Sala Ginori, where the altarpiece painted for the church of the Confraternity of San Girolamo in Arezzo (and today also kept in the provincial capital, but in the local Museo Nazionale d’Arte Medievale e Moderna) is presented, a masterpiece of Signorelli’s last years, which is currently being restored: a worksite open to the public.

Even with a judicious selection, as we have seen, the exhibition fully succeeds in the double intent of touching, from a bird’s eye view, on the main developments of Signorelli’s language, and of presenting to the public the originality and qualities of one of the most relevant artists of his time, although full recognition of the consequences of Luca Signorelli’s art is a relatively recent acquisition. It can safely be said that, just as from the delicacy of Perugino descends the grace of Raphael, so from the vigor of Luca Signorelli descends the power of Michelangelo: among the frescoes of the chapel of San Brizio, among those scenes so powerful and terrible that they describe the end of the world as no one had ever succeeded in doing before the Cortonese, one can already glimpse the drama that Michelangelo will unfold on the walls of the Sistine Chapel. One could define Signorelli as a painter of opposites, adopting an image that Robert Vischer, the first scholar to monograph the Cortonese (in 1879), used to point out the contradictions with which the artist habitually and skillfully played with, showing himself to be “pious and worldly,” “dark and mild,” “devout and fierce.” And yet, one might add, dreamy like the Umbrian artists and firm like the Florentines, disciplined and nonchalant at the same time, elegiac and dramatic, measured and wild, ancient and modern, rough and rhythmic, confused and bold. For Vischer, Signorelli was “the boldest and most ambitious leader” among the painters who took art by the hand and accompanied it through the “great movement toward the sixteenth century.”

Too bad the public is not allowed to photograph the works. Let the organization revise its policy, it is always in time: let it be done as it is done on such occasions, and put appropriate icons next to the works for which the lenders have arranged the anachronistic ban on taking a picture to take with them to cherish the memory of a fine exhibition. It is, frankly, not permissible for all works to be banned from being photographed because, as was reported to this writer by a probation officer, they did not want to identify the “forbidden” works one by one, so to speak, and it was then decided to extend the ban to all of them. Let the freedom of selfies be allowed, let the harmless self-shots in front of Signorelli’s masterpieces be allowed, let the public not be prevented from going home with a photo of the Annalena Crucifixion, the VolterraAnnunciation, the two Atlanta tablets, the fragments of the Matelica Altarpiece all put together: many may not get the opportunity again. And it is also the only exhibition scheduled this year on Signorelli, struck by a misfortune his colleague Perugino did not have. Both died in the same year, both fundamental to developments in 16th-century art, but how different still is the regard for them, when one considers that in Umbria a craze seems almost to have broken out for Pietro Vannucci, but no major initiatives have been received for Signorelli. The Cortona exhibition then becomes all the more valuable as a reminder that Signorelli was no less relevant than his Umbrian colleague.

It is natural, finally, that the contents of the exhibition should extend outside the walls of the MAEC: the visitor will delve deeper, meanwhile, by climbing through the alleys of Cortona, perhaps going as far as no. 12 Via San Marco, where there is the house in which Signorelli spent his last days. It is precisely the painter’s house that could become a sort of metaphor for what happened to his works that were once scattered throughout Cortona: those who wanted to find some trace of it in the churches of the city, anciently adorned with works by Luca Signorelli and his workshop, would be going around almost in vain, and would do better to concentrate on the church of San Niccolò, where there is still preserved the altarpiece that Signorelli painted on both sides (the side facing the faithful shows a Lamentation over the Dead Christ, a “masterpiece of collected silence,” as Stefano Casciu called it, despite the rather crowded composition). The rest, however, is gathered between the MAEC and the Diocesan Museum, while just outside the walls one will visit the aforementioned church of San Domenico to admire the panel painted in 1515 for the chapel that housed the relics of St. Blaise, and further distant from the center is the so-called Palazzone, the former residence of Cardinal Silvio Passerini, who commissioned Signorelli, by then well advanced in years, to paint some frescoes (the Baptism of Christ and the Sibyl, among his last works, can be seen: Tradition would have it that the artist lost his life when he fell from scaffolding while working on frescoes for the cardinal), and the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie al Calcinaio, which was to have housed an altarpiece by the artist that was never painted due to his passing. Helping visitors on their journey to Cortona and beyond to really discover all of Signorelli is a clever initiative by the exhibition organizers, who make available to everyone (via special leaflets and through the website www.signorelli500.com) the itineraries “Traveling with Signorelli in his lands,” which list all of Signorelli’s works in Cortona, Arezzo and the Valdichiana, Valtiberina, along the Lauretana and in Umbria between Perugia and Orvieto, with routes that can often be completed in a day. And which collectively justify a trip to these wonderful lands.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.