by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 16/05/2017

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition Warhol vs. Gartel. Hyp pop in Lucca, Lucca Center of Contemporary Art, through June 18, 2017.

In the not-too-distant past, one of the greatest contemporary Italian writers wondered whether Andy Warhol (Pittsburgh, 1928-New York, 1987) could be ascribed to the category of the tamarins, and the answer could only be soundly assertive. Indeed, it went so far as to argue that Warhol had been the leader of the tamarins: after all, one of the first critics to deal with him, Simon Wilson, wrote that pop art was art liberated from the dignity of high art, that is, art as it had been understood up to that time. Andy Warhol’s art could afford, at least in the first instance, to avoid looking at the past in order to draw heavily on a present made up of mundane idols, comic book characters, nightclub goers, and mass-produced products destined for the lowest consumption: and nothing is more tamaronic than closing one’s eyes to the past and wandering among the shelves of a supermarket or leafing through a glossy magazine (obviously read by an audience of tamarins) to find sources of inspiration. This basic and fundamental peculiarity of Andy Warhol’s art is well captured by the exhibition Warhol vs. Gartel. Hyp pop, currently underway in Lucca: without mincing words it informs us that “the absolute protagonist of the American artist’s works would become the object understood as the common product, the prerogative of the masses, which regardless of its original form or function was a well-solid emblem in the collective imagination.”

|

| Andy Warhol’s icons in the first room of the exhibition |

But of course, Andy Warhol’s art was not just that. Arthur Danto wrote that in Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (we have a reduced-size specimen in Lucca in the exhibition) there are the aspirations of a person born into poverty who is fascinated by a kitchen filled with new products, there is a reaction to Abstract Expressionism that is substantiated by a celebration of the consumer society that Abstract Expressionism instead rejected (and consequently there is what Danto calls a “philosophical shift” from rejection to approval), there is an ideal charge identical to that of the Pre-Raphaelite painters who, to exorcise the ugliness of the world around them, filled their works with unblemished knights, floral arrangements and graceful Madonnas. But a tamarin cannot be asked to paint a Madonna and Child, said the great writer quoted in the opening: at most, he will strive to draw the profile of a sports car. The emphasis has been placed on the undoubted Tamarist substratum of Andy Warhol’s art because, if it is indeed necessary to speak of a challenge with Laurence Gartel (New York, 1956), as is openly implied in the press release presenting the exhibition in Lucca, this very special tussle, a bit like “Maciste against the Sheik”, cannot but take place on the level of Tamarism. On the one hand, the philosophical and aestheticizing one of Andy Warhol. On the other, the visionary, charged and chaotic one of an outsider like Laurence Gartel whose depth seems yet to be investigated.

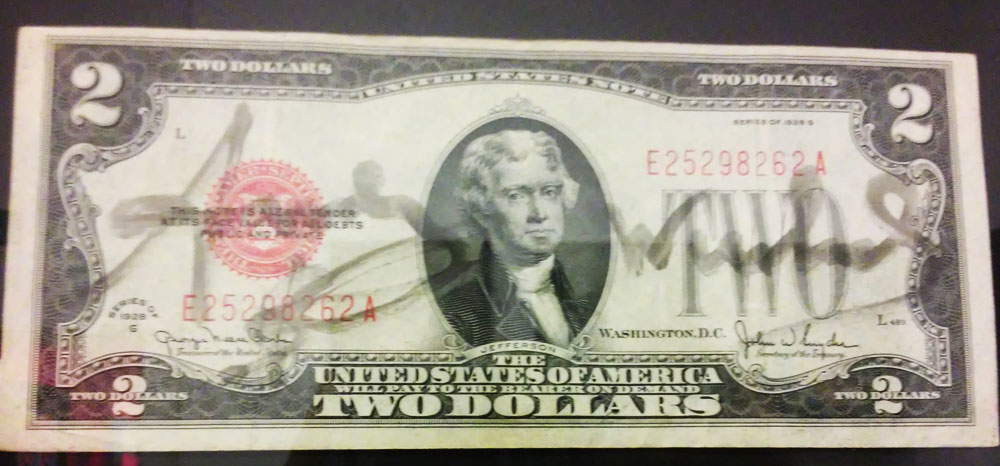

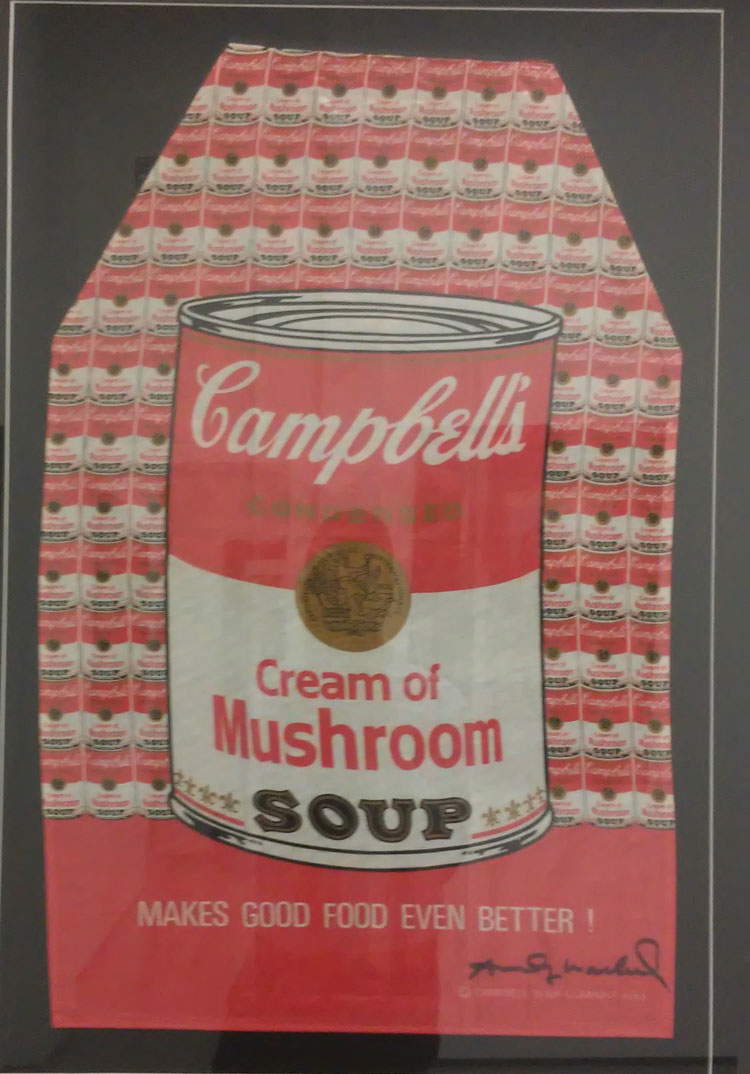

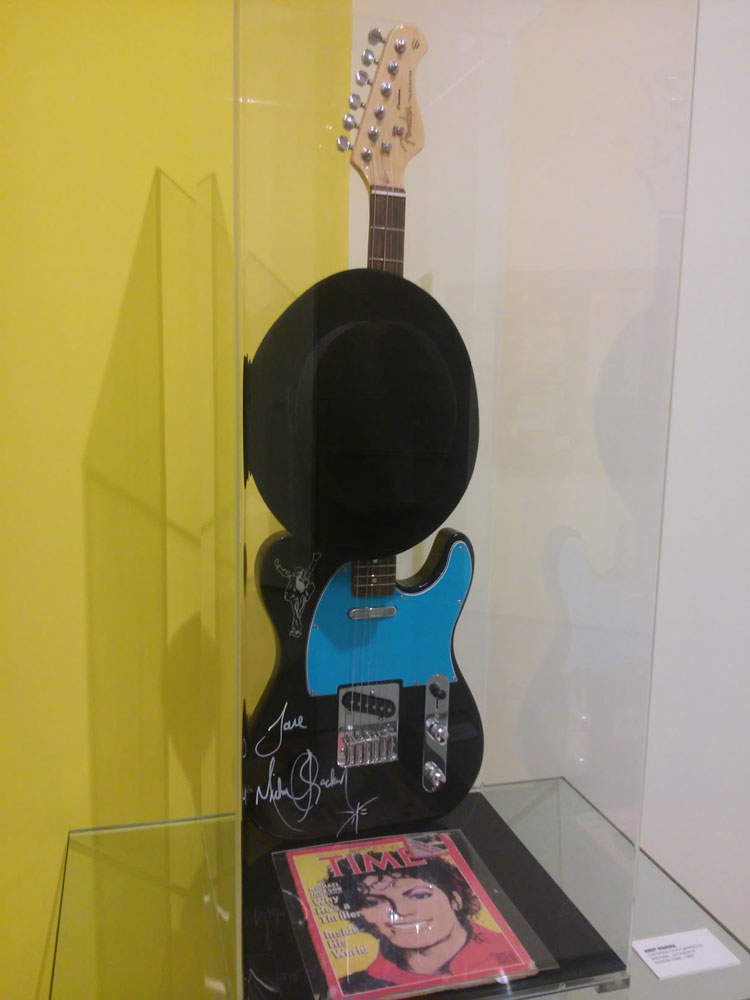

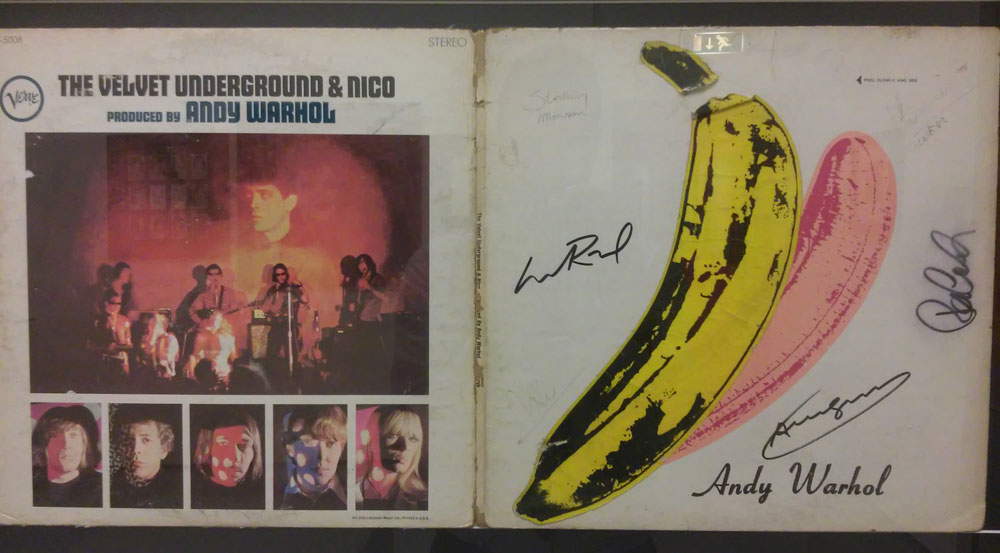

The comparison, however, is left to the last rooms of the exhibition. First, the classic Warholian sampler is reviewed, which opens with the typical Marilyn paintings that occupy an entire wall and that here in Lucca the captions inform us are “after Andy Warhol,” with the result that the exhibition (it is not known whether knowingly or not) thus pays the best possible homage to reproducibility, to the seriality that constituted the founding basis of Warholian reflection on art. A task well fulfilled also by the two-dollar bills(2 Dollar Bill. Declaration of Independence) that came out of Warhol’s presses exactly as if they had come out of the US Mint: all identical, indistinguishable from each other, and without the artist putting his own hand on them (signature for authentication aside). It is art without the artist, it is the ultimate celebration of the Warholian assumption that “if one cannot afford a painting, one should still have access to the poster,” it is art that, also in an anti-rhetorical function, celebrates as much the “little everyday fetishes” (an effective expression Michele Dantini uses for Campbell soups, obviously well present in Lucca, indeed: the climax of such spic and span everyday fetishism is perhaps the kitchen apron reproducing cans of peeled tomatoes) as much as the great fetishes of the masses, from Hollywood actors to the most celebrated singers. Again, what better way to celebrate the fetish than the fetish itself? And so it is that the Lucca exhibition is populated with memorabilia that is sure to amuse the visitor, from Michael Jackson’s hat to the guitar signed by individual members of the Rolling Stones via the cover of The Velvet Undergound & Nico to culminate with the apotheosis of the room dedicated to the covers of Interview: a true Warholian pantheon of choice as well as a pop iconostasis that exerts a power bordering on the religious on those who observe the two walls crammed with glossy portraits of stars.

|

| After Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe (1985; silkscreen on paper, all 84.5 x 84.5 cm) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Two dollars bill (declaration of independence) (1980s) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Campbell’s soup pepper pot (1968; silkscreen on paper, 88 x 58 cm) |

|

| Campbell’s soup apron. |

|

| Michael Jackson’s Memorabilia |

|

| The cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico |

|

| The room with the covers of Interview |

And a star would also constitute the first trait d’union between Warhol and Gartel: a widespread rumor has it that a young Gartel taught Warhol, through a curious reversal of traditional roles, to use the Amiga computer to “paint” Debbie Harry with a mouse instead of a paintbrush. A piece of information found exclusively in Gartel’s biographies: in an article a few years ago, the U.S. edition of Wired aptly wrote that the artist claims (but the verb to claim in English also takes on the nuance of “to claim”) that he was the one who mentored Andy Warhol in the use of computers to make digital art. But if one does a quick Google search to get a sense of who the character is, one can also pass over what will immediately appear to us as useless philologist’s niceties: we will become acquainted with a pudgy New Yorker transplanted to Florida who looks like he just escaped from an episode of South Beach Tow. Gray hair, long and straight to frame a perpetually smiling face, improbable blouses open across the chest with a gold chain prominently displayed (or with collars fastened by ties in the loudest patterns), big cars decorated with patchwork of his own invention (his Art Cars seem to find some success): in short, sobriety is not exactly at home.

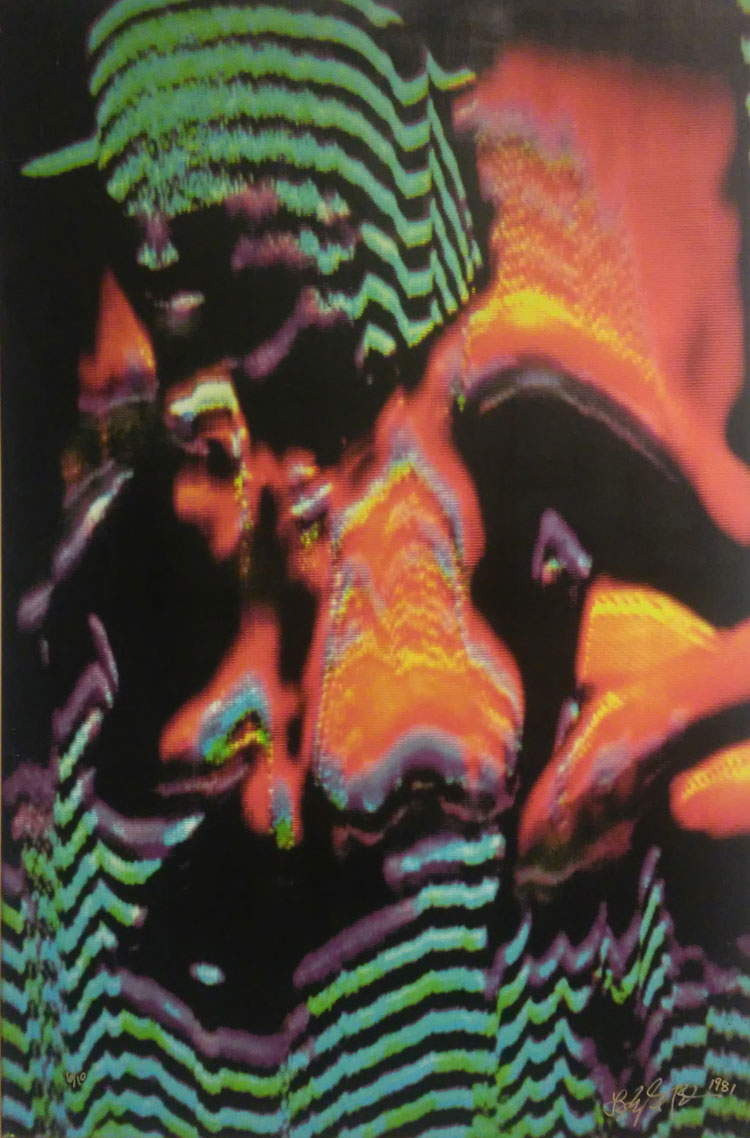

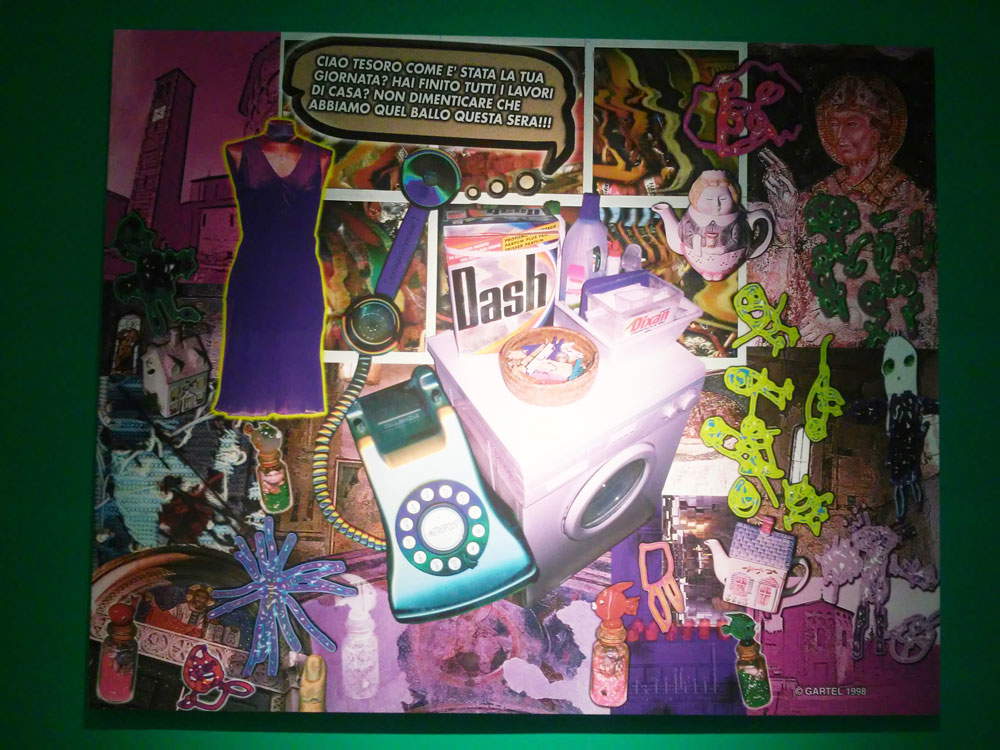

However, it is true that Gartel had to start a bit earlier than Andy Warhol to make digital art. In the exhibition we have early attestations of his abilities with, for example, a Nina and a Dual personality from 1979, or a French nude from 1981: these are early elaborations of images on which Gartel intervened at first with all-too-simple operations (e.g., by exaggerating contrasts, or altering saturation and color balance), and then with increasingly invasive distortions (in French Nude, acid waves created with the synthesizer that Gartel uses to violently color his works, or to bring down brutal abstract forms on his characters, make an appearance). On a philosophical level, these hard-hitting images are justified by reading the works of Philip K. Dick, who imagines dystopian futures made up of worlds where humans and machines are in conflict with each other, where the boundary between real and illusory is increasingly blurred, where alienation becomes almost a paradoxical necessary condition to better understand the world. From here to the visionary works of the 1990s, the step is short: the preferred method becomes the virtual collage with which Gartel gives life to frenetic compositions such as Downtown (a kind of “ideal city” of digital tawdryness that reinterprets Dickian anxieties in a grossly good-natured and facile key) and Glory, a post-Warholian celebration of consumer society, from which the comparison between the two artists can begin.

|

| Some of Laurence Gartel’s works on display in Lucca |

|

| Laurence Gartel, Nina (1979; digital print, 86 x 115 cm) |

|

| Laurence Gartel, French Nude (1981; digital print, 120 x 78.5 cm) |

|

| Laurence Gartel, Glory (1998; digital print, 119.5 x 148 cm) |

|

| Laurence Gartel, Downtown (1996; digital print, 120 x 180 cm) |

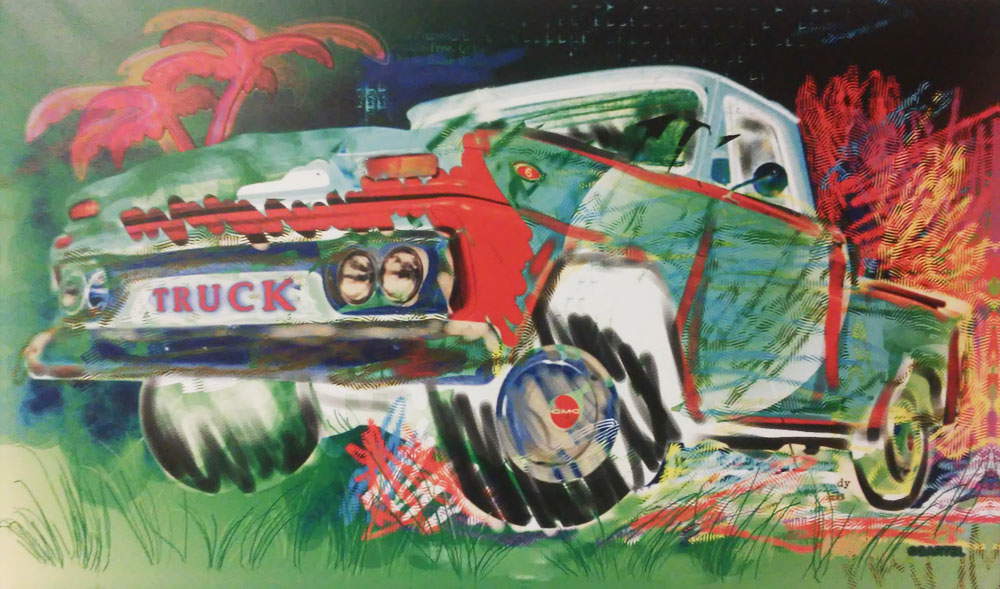

So if Warhol was the leader of the tamarins, Gartel is surely the more ambitious one, the one most eager to show off, the one most indelicate and loud. It is not enough for him that Coca-Cola cushions our existences with its pounding advertisements: his wish is that the brand crosses planetary boundaries to spread out into the universe, and to do this he imagines the well-known red brand floating above a black background symbolizing cosmic space. For Gartel, it is not enough to celebrate the myths of the present, but also to project such images “into plausible futures, into imaginative scenarios, into truly dreamlike dimensions.” it is a kind of shot-forward nourished by science fiction and triggered by a society increasingly prey to uncertainty, within which the myths, celebrated by both Warhol and Gartel, no longer have the value they once had, and which probably needs to imagine itself in ever new forms, basing such work of regeneration on the dream that for Gartel, as he himself admits, is a typical element of the human being, capable more than any other of distinguishing him from the machine. The circle of tamarrism concludes worthily with some iconographic similarities: the example of Andy Warhol’s trucks aptly recalled by Gartel’s crude Gmc Truck, which, truncated and ignorant, launches itself out of a whirlwind of psychedelic colors partly a graphic effect of Windows Media Player, partly the backdrop on which the kings of musical tamarrism, namely Kiss, wiggled in the very caustic video of Psycho Circus.

|

| Laurence Gartel, Coca-Cola (1996; digital print, 115 x 90 cm) |

|

| Andy Warhol, Truck (1985; lithograph on paper, all 17 x 17 cm) |

|

| Laurence Gartel, Gmc Truck (1995; digital print, 86.5 x 114 cm) |

With Warhol vs. Gartel. Hyp pop the Lucca Center of Contemporary Art breaks out of the logic of the usual exhibition on Andy Warhol (and fortunately, because there would also have been an aggravating factor: Warhol had already been on show in Lucca just five years ago), nevertheless making acourageous operation in proposing an artist like Gartel, who is rather self-referential, who seems cut off from the circles of art “that counts,” and who owes his fame more to the à la page names for whom he has worked than to a critical fortune yet to be achieved (or at best scarce). Time will tell whether curator Maurizio Vanni was right in proposing this comparison: for now we can limit ourselves to enjoying an intelligent exhibition that, yes, will give food for thought on “the changing meaning of art in an age that imposes a continuous confrontation between man and machine,” but that above all is a lot of fun.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.