In 1787, commenting on the mausoleum of Pope Clement XIV that Antonio Canova had just completed in the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Rome, the learned writer and theorist of neoclassicism Francesco Milizia wrote in a letter, “Canova is an antique, I don’t know whether from Athens or Corinth. I bet that if in Greece or in the most beautiful time of Greece one had to sculpt a pope one would not have sculpted other than this. I wish that young artists would set themselves on the good path of Canova and that the fine arts would finally rise again.”

It was the attack of what would be, for the duration of the sculptor’s artistic activity, an almost unanimous chorus: Canova enjoyed a ’boundless admiration that few other artists managed to know in his lifetime. Such popularity exploded precisely with the realization of the tomb of Pope Ganganelli, which was followed by that of the funeral monument dedicated to Clement XIII Rezzonico, placed in St. Peter’s and unveiled to the public in 1792. Two important commissions, entrusted to a non-Roman and very young artist, who thanks to them, in his early thirties, could be said to be established in a very competitive working environment.

Canova, originally from Possagno in the Veneto region of Italy, had first stayed in the papal city from November 1779, for a rather short period. The artist, who had financed the trip with the sale of his sculptural group Daedalus and Icarus, had traveled to Rome to train, to finally be able to appreciate in person those many ancient sculptures he had known and studied at the Venice Academy through copies. Returning to the Veneto after seven months, Antonio returned to Rome at the end of 1780 and stayed permanently, spending, in all, more than forty years of his life there. It is precisely the relationship between the sculptor and the city that forms the main thread of the exhibition Canova. Eternal Beauty, set up at Palazzo Braschi in the heart of the capital, and open to the public until next March 15. In fact, already the choice of the title, as confirmed by the curator Professor Giuseppe Pavanello himself, contains a clear reference to Rome, the eternal city, to which an exhibition finally returns the role it played, in the context of the narration of the artist’s professional career.

The exhibition, promoted by Roma Capitale and Arthemisia, and organized with Zètema, in collaboration with the Accademia di San Luca and the Gypsotheca e Museo Antonio Canova in Possagno, is divided into thirteen thematic sections, and offers for public observation more than 170 pieces (from Italian and foreign facilities) including marbles, plaster casts, paintings, clay models, drawings, engravings, documents and photographs.

|

| Exhibition hall Canova. Eternal Beauty |

|

| Canova Exhibition Hall. Eternal Beauty |

|

| Exhibition hall Canova. Eternal beauty |

|

| Canova exhibition hall. Eternal Beauty |

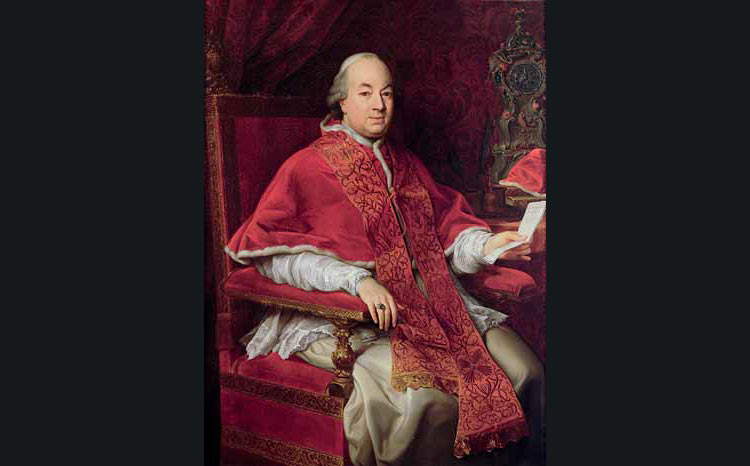

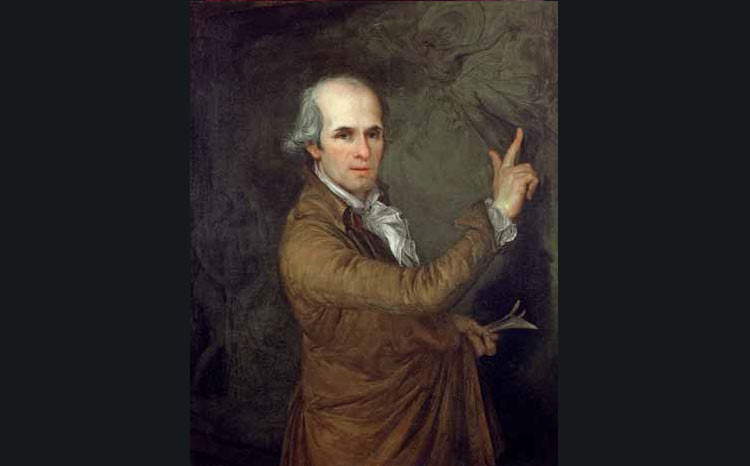

Significantly among the paintings that welcome visitors we find the portrait of Pius VI Braschi, who wanted the building of the Palace, by the hand of the well-known portraitist Pompeo Batoni, and that of Canova, executed by his collaborator Martino De Boni. The pope who in the late 18th century erected the building in which the exhibition is housed, and the artist to whom it is dedicated.

The next two rooms display pictorial and sculptural portraits of some of the best-known figures who animated the Roman cultural scene in the years of Canova, Pompeo Batoni, Raphael Mengs, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, and Angelica Kaufmann; there is also room for a pair of large canvases of mythological subject matter made by the Scottish painter Gavin Hamilton, a friend and influential supporter of Antony.

Rome in the second half of the 18th century was an almost politically irrelevant city that nevertheless still held the role of capital of the arts, not least because of the priceless ancient art-historical heritage that intellectuals and artists from all parts of Europe flocked to admire and study. Among them was the aforementioned Winckelmann, the German archaeologist and art critic and father of Neoclassicism. The scholar arrived in Italy in 1755, a few decades after the resounding discoveries of Herculaneum and Pompeii, and settled in Rome for thirteen years, however, making short trips that took him across the Peninsula, until 1768, the year of his death, which occurred in Trieste. Winckelmann and Canova never met, and yet the German’s writings were certainly not unknown to the Venetian sculptor.

The recovery of the composed perfection that was characteristic of Greek statuary (known at the time mainly through Roman copies) was to be, according to Winckelmann, the main aspiration of modern art, which only through a return to the principles of compositional simplicity, formal purity, harmony, and balance, pursued by the masters of classical Greece, could aspire to greatness.

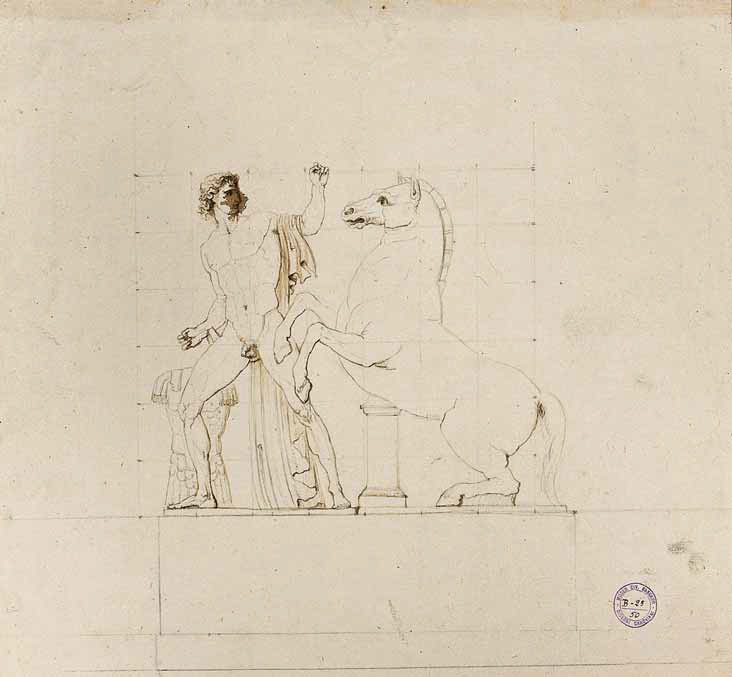

However, what the archaeologist recommended to his contemporary artists was imitation, and never mere copying, of the masterpieces of antiquity: exactly the conduct that Canova would hold years later. “Copies I do not make,” he wrote to the painter Marcello Bacciarelli, who had asked him for replicas of ancient statues on behalf of the king of Poland. Rather, it was appropriating the style of the old masters that interested the sculptor, “sending it to his blood” and then “making one’s own by always having an eye on beautiful nature,” as he himself stated in a letter addressed to the Frenchman Quatrèmere de Quincy. And to achieve this, of course, assiduous study of the works was essential. Thus, in one of the rooms at the beginning of the itinerary are visible some of Canova’s drawings reproducing the Dioscuri del Quirinale, Roman replicas of bronze originals, theHermes,at the time believed to be an Antinous, and the Torso, the latter both called the Belvedere because they were placed in the famous Cortile in the Museo Pio-Clementino in the Vatican.

Moreover, the exercise by means of graphic reproduction of ancient works was considered the basis of artistic training; thus alongside Canova’s studies we see numerous drawings by other artists and plaster casts, employed, the latter, where access to the originals was not possible.

|

| Pompeo Batoni, Portrait of Pius VI (c. 1775; oil on canvas, 135 x 98 cm; Rome, Museo di Roma, inv. MR 5669) |

|

| Martino De Boni, Portrait of Antonio Canova (1800-1805; oil on canvas, 91 x 74 cm; Rome, Museo di Roma, inv. MR 1410) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Study from the Colossi of Monte Cavallo (ink on ivory paper, 352 x 382 mm; Bassano del Grappa, Museo Civico, inv. B 23.50) |

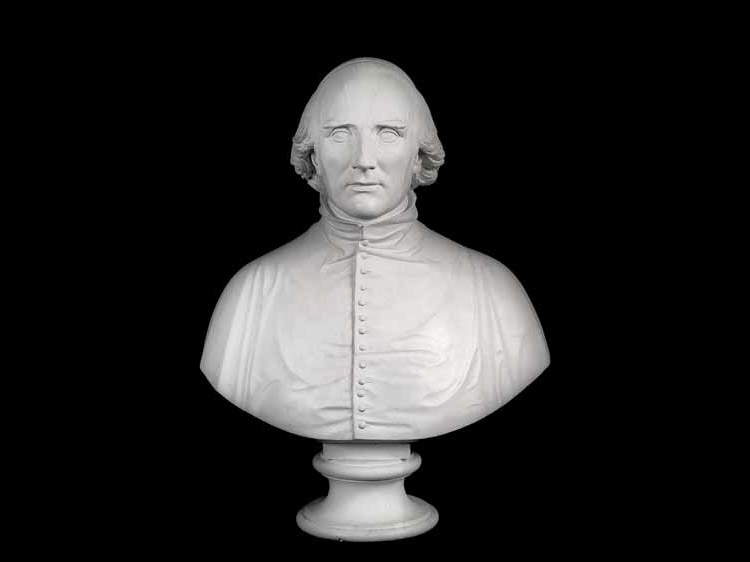

Two rooms dedicated to the funerary monuments mentioned at the beginning of this article follow. This is one of the richest sections of the exhibition, in which drawings and terracotta models illustrate the developments that, starting from generic meditations on the theme of burial, led to the sculptor’s two early masterpieces. The commissions were given to Canova within a short distance of each other, so, at least for some years, he worked on both projects simultaneously. The statues of the pontiffs that dominate the monuments are very effective, and very different from each other: one depicts Clement XIV enthroned with his right hand raised in an imperious gesture, while the other portrays his predecessor of the same name, Rezzonico, kneeling in prayer and stripping off his triregnum, placed on the ground beside him. From the latter work was taken the plaster bust of the pope, which, displayed in the exhibition, allows a close appreciation of the vivid realism with which the grave face, with its strongly irregular features, is reproduced. It is one of many plaster casts that appear in the exhibition itinerary to replace the marbles, often, as in this case, evidently impossible to move.

Further on, however, we encounter two marble statues, a Cupid and a Penitent Magdalene, from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Strada Nuova Museums in Genoa (Palazzo Tursi), respectively. Presented in the same setting, however, the works are very different in character. TheCupid rotates with the pedestal allowing the viewer to admire it in its entirety without having to move, and it is one of five (counting the one housed at the Palazzo Comunale in Bologna, recently returned to Canova by Antonella Mampieri) executed by the artist during his career. The sculpture, which Canova himself considered the best of his own of the same subject, is a felicitous example of his predilection and talent for making statues depicting young naked bodies, pairs of lovers or single figures, declinations of that tendency toward the graceful and gracious that was at the root of some of the criticisms levelled at the artist by art historian Karl Ludwig Fernow, among the very few of his contemporaries who did not particularly like him. Indeed, Fernow wrote in 1806 that the Possagno sculptor “succeeds only in what is tender, pleasing, youthful [...] while for the most part his works of signifying, energetic and heroic figures do not succeed well, for the reason that they are foreign to the sphere of his wit and way of feeling.”

Also displayed in front of the statue is an Eros from the second century CE, suggesting that dialogue between Canova’s works and ancient models to which, as we shall see, ample space is given in the next room.

Also referable to the same years as the Hermitage statue is the Magdalene. This striking sculpture, the artist’s first to land in France, appears on display positioned with its back to a mirror, exactly as it could be admired in the nineteenth century in the Paris palace of Giovanni Battista Sommariva. The purpose was (and is), evidently, to make her sensual naked back visible as well.

As the subject required, the saint was depicted in all her collected contrition, equipped with a skull and crucifix, crouching, with her head recumbent and tears streaming down her face, and the intensity

of the feeling she expresses is almost heightened by the juxtaposition with the portrait of the young pagan god, of a beauty, on the contrary, haughty and imperturbable.

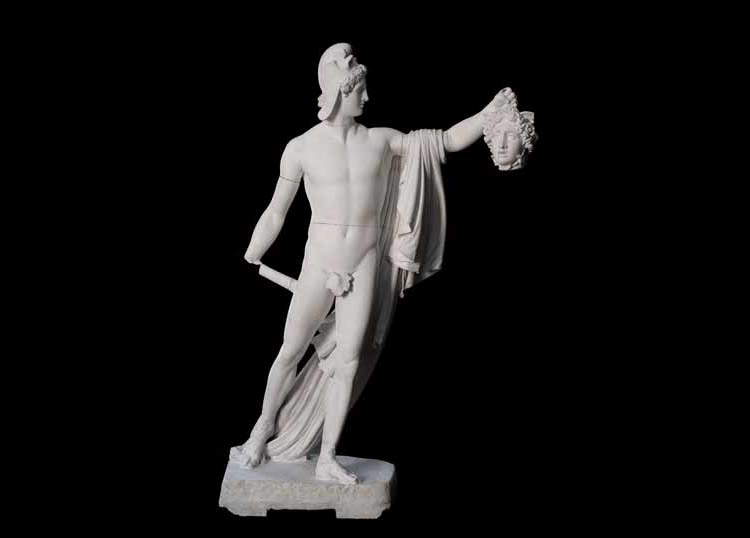

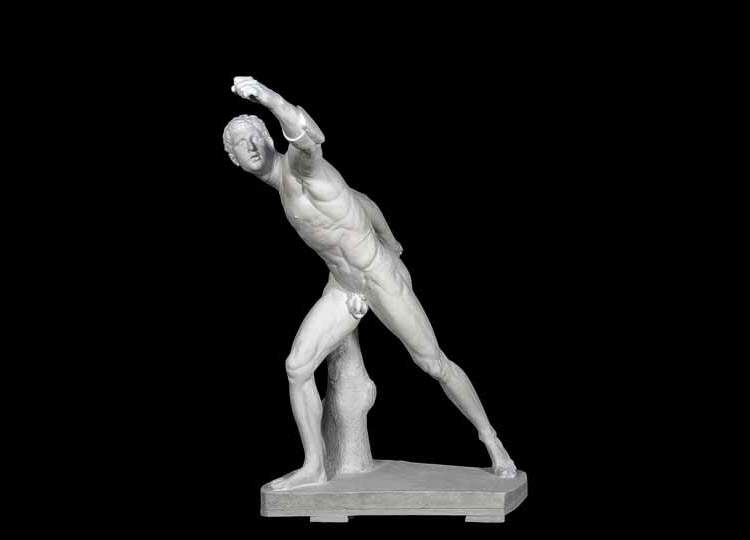

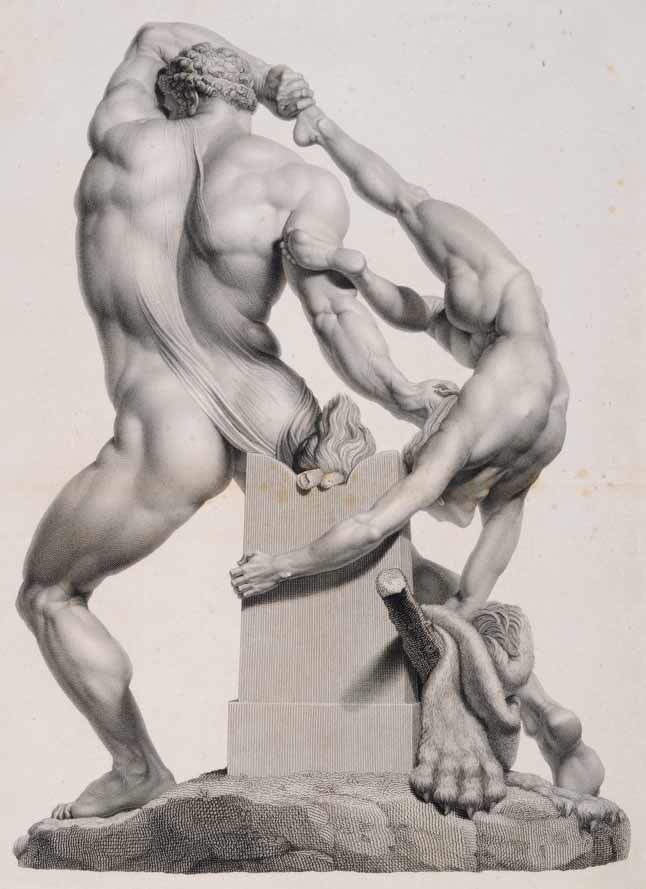

In the next passage of the exhibition itinerary, two plaster casts taken from ancient works are juxtaposed with as many plaster casts from Canova sculptures: theApollo of Belvedere and the Borghese Gladiator alongside the Perseus Triumphant and the Creugating. These plaster reproductions were made by Canova and his collaborators in the early 19th century at the request of Count Alessandro Papafava, who wanted to place them in the salon of his Paduan palace. And the decision to re-present their juxtaposition in this context is truly significant, at least for two reasons. The first is that by doing so, a historical setting has been re-presented, the plaster casts have been moved, while leaving intact the relationship that binds them, and that was at the origin of their very creation, thus allowing one to appreciate, even outside the palace, both the works and the intuition of the commissioner. The second reason is that it is precisely this comparison between ancient models and modern creations, desired by Papafava, that is an expression of what is called in the exhibition panels “the perfect theorem of neoclassical taste,” and an illustration of the principle that was at the basis of the cultural movement: the emulation of the old masters, the recovery of the spirit that informed their creations.

Incidentally, to one of the four sculptures whose plaster cast is presented here, theApollo of the Belvedere, a probable Roman copy of a 4th-century B.C.E. Greek bronze, Winckelmann devoted some of the most inspired pages of his critical production, helping to make it one of the main models of reference for the artists who had embraced his precepts, including, evidently, Canova. In his text History of Art in Antiquity, published in 1764, the archaeologist thus described the marble still housed in the Vatican: “the statue of Apollo represents the highest ideal of art among the ancient works that have been preserved down to us. The artist set his work on a purely ideal concept and used the material only as much as was necessary to express his intent and make it visible.” He further notes that “nothing here reminds one of death or earthly miseries. Neither veins nor sinews warm and move this body, but a heavenly spirit, like a placid river, fills all its contours.” Fatigue, apprehension and turmoil find no place in this depiction of Apollo, who also has just killed the fearsome Python, only what Winckelmann interprets as a slight motion of disdain hovering over his face, without however affecting the stillness emanating from the harmonious marble image of the god.

As a result of the Treaty of Tolentino, imposed in 1779 by France on the Papal States, the Urbe was stripped of many famous works, including the Belvedere masterpiece. Thus, at the beginning of the next century, the newly elected Pope Pius VII decided to fight back and show Napoleon that Rome was capable of rising again even after the very serious spoliations it had suffered, and that, as Leopoldo Cicognara wrote, “if substances, lives, and monuments can be robbed, the genius of studies and the arts, the only indigenous resource of our soil, will not be carved up.” In 1802, therefore, the pontiff purchased the Perseus Triumphant that Canova had executed the year before, to place it on the pedestal left empty by the stolenApollo. And there the sculpture remained until 1815, the year of the return to Rome, thanks to the efficient diplomatic work done by the Venetian artist himself, of a substantial part of the previously seized works, including theApollo. Following this important recovery, the Perseus was moved to restore the statue of the god to its rightful place, and placed along with two other Canova sculptures, the Pugilatori, in Canova’s Cabinet, also inside the Cortile Ottagono, where they remain to this day.

So in the hall of Palazzo Papafava and, at the moment, in a room of Palazzo Braschi, the plaster of the ancient work and that of its temporary replacement can be appreciated side by side. Obviously, Canova’s sculpture (which, as mentioned, was made before Pius VII acquired it and thus was not conceived by its author to take the place of the other one) represented much more than a mere substitute: it constituted the definitive confirmation of the sculptor’s great abilities, and of the enormous esteem in which he now enjoyed. Moreover, Canovian Perseus, which was executed precisely by looking at the statue ofApollo of the Belvedere, is a most effective example of that practice of imitating the ancient, which is never reduced to mere copying. If, in fact, the similarities between the two statues are immediately obvious, in posture and expressive intention, important are also the differences (net of those arising from the fact that these are two different mythological subjects), which we catch mainly in the inverted pose of the legs, in the rendering of the hair, and above all in the course of the chlamys, and which make Canova an interpreter rather than a copyist.

Next to this Apollo del Belvedere-Perseus Triumphant comparison, we find another: Gladiator Borghese-Creugante. Again the reproduction of an ancient marble, dating from the first century B.C. and executed by the Ephesian Agasias, and that of a creation by Antonio Canova, this time depicting a boxer. We are in the field of figures that Canova in a letter addressed to Quatremère de Quincy called “of stronger character,” in which the performance of vigorous, violent action is central, that field in which, according to Fernow, Canova did not excel. Regarding this opinion of the German critic, in an essay contained in the exhibition catalog, Professor Antonio Pinelli observes that “it is difficult not to admit that Fernow’s thesis hits the mark in some way,” and going into the merits of Canova’s works he writes: "Of his ’heroic’ statues, only the Perseus has the irreproachable felicity of his greatest masterpieces. The other plastic groups, though exceptional, in their excessive and strained poses, in their ostentatious virtuosity, seem to betray the weariness and uneasiness of the sculptor who does violence to himself."

The plaster of the Borghese statue (now in the Louvre) contributed, along with other ancient marbles long studied and more faces drawn by the artist, to the conception of the Canovian statue. The Creugante was sculpted by Canova beginning in 1795, along with another sculpture, the Damosseno. The two works, designed for close placement, depict the boxers who, according to Pausanias’ account, allegedly faced each other during the Nemean games, and both were purchased by Pius VII along with the Perseus, to be placed with it in the Courtyard in the Vatican (today they are in the aforementioned Canova Cabinet).

Further on in the exhibition one encounters another plaster cast of the Creugante, this time side by side with the one taken from the statue of the other boxer. Here it is possible to observe the pair of athletes up close with the help of small flashlights; thus, a type of fruition already envisaged by the Antonio Canova Gypsotheca and Museum (from which the two plaster casts come, as do many others in the exhibition) and suggested by the sculptor himself, who used to show his works, to the many who flocked to visit his studio, in the dark by candlelight, in the conviction that only in this way was it possible to fully appreciate the details and refinement of the execution.

|

| Scope of Antonio Canova (Giovanni Tognoli?), Clement XIV (pencil and gray watercolor on yellowed white paper, 582 x 465 mm; Venice, Museo Correr, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, inv. cl. III, 1472) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Clement XIV (c. 1783; terracotta, 45 x 40 x 24 cm; Possano, Gypsotheca and Museo Antonio Canova, inv. 13) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Bust of Clement XIII (post 1792; plaster, 131 x 91 x 80 cm; Carrara, Accademia di Belle Arti, inv. Ant. 83) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Winged Cupid (1794-1797; marble, 142 x 54.5 x 48 cm; St. Petersburg, The State Hermitage). © The State Hermitage Museum, 2019 Photo by Alexander Koksharov |

|

| Antonio Canova, Penitent Magdalene (1796; marble, 95 �? 70 �? 77 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova - Palazzo Tursi, inv. PB 209) |

|

| Roman art, Centocelle-type statue of Eros (2nd century AD; fine-grained white marble, height 165 cm; Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 6353) |

|

| Antonio Canova’s Scope Former, Apollo del Belvedere (1806; plaster, 230 �? 130 �? 90 cm; Padua, Palazzo Papafava, private collection) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Perseus Triumphant (1806; plaster, 230 �? 130 �? 90 cm; Padua, palazzo Papafava, private collection) |

|

| Former of the Scope of Antonio Canova, Gladiator Borghese (1806; plaster, 157 �? 132 �? 66 cm; Padua, palazzo Papafava, private collection) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Creugante (1806; plaster, 218 �? 125 �? 66 cm; Padua, palazzo Papafava, private collection) |

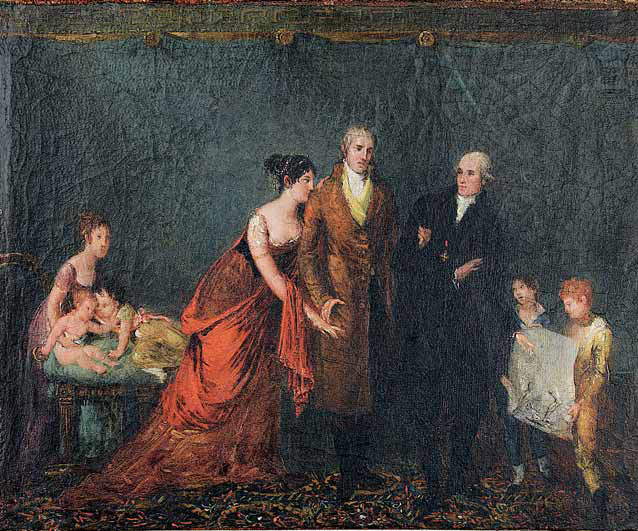

Remaining in the sphere of Canova’s sculptures of “strong character,” the exhibition does not neglect to deal with the celebrated Hercules and Lica group, housed right in Rome at the National Gallery of Modern Art. Again on the subject of Fernow’s oft-mentioned critical remark, Pinelli again writes that “at the turn of the century Canova himself, prodded and almost obsessed by this objection, did everything he could to disprove it with facts, dealing with increasingly dramatic, violent and even truculent themes.” Thus in 1815, finally finished after a long gestation that began 20 years earlier, the sculptural group depicting the mythological hero and the hapless Lica was delivered to the buyer Giovanni Torlonia.

In the exhibition, GNAM’s masterpiece is recalled by a canvas, according to some executed by Martino de Boni, according to others by Canova himself, which returns us to the moment when the sculptor showed the Torlonia family the design of the work he was working on, a small bronze, a drawing and engravings. The latter are particularly interesting; executed one by Giovanni Folo, the one with a frontal view, and the other by Pietro Fontana (Canova’s favorite artist) who portrayed the work seen from behind, the prints are an example of the Venetian master’s use, a shrewd entrepreneur, of having his statues translated into engravings, engravings that were then circulated so as to publicize his creative skill.

There were many artists and craftsmen with whom Canova collaborated: engravers, indeed, but also painters, plaster molders, sculptors, carpenters, and lustrators, and they all crowded his studio in Vicolo delle Colonnette. A substantial section of the exhibition is devoted precisely to recounting the activity of this studio, which, moreover, after the resounding success of the funerary monuments created by Anthony for Clement XIV and Clement XIII, became a true pilgrimage destination for the curious, art connoisseurs and travelers who came to Rome on their Grand Tour.

A small painting from the Museo Civico di Asolo and executed by Roberto Roberti depicts the building as seen from the outside; it is a very interesting work documenting the original appearance of the studio, on whose walls Canova had had various archaeological pieces (some of which have disappeared) placed.

Directing and administering the atelier was the sculptor, and close friend of Canova, Antonio D’Este, who also had the delicate task of selecting the marbles that would later be used for the sculptures. The exhibition presents a number of works by this artist, including the plaster cast that belonged to Senator Giovanni Falier, taken from a very peculiar herma depicting Antonio Canova and on the side, in small print, D’Este himself.

Another relevant personage, very close to the Venetian master and his close collaborator, was his brother on his mother’s side, Abbot Giovanni Sartori, who appears in the exhibition portrayed together with Antonio in a canvas by Martino De Boni lent by the Museo Civico of Bassano del Grappa. The clergyman, who lived for many years alongside his brother, was his secretary and was named his universal heir. Thus, upon the artist’s death, Giovanni took over the direction of the studio by having the unfinished marbles completed, and then arranged for the sale of the Roman property. The building that housed the atelier was also sold, and all the movable property remaining there, including the plaster casts, was transferred to Possagno. Thus was born the Gypsotheca, next to Canova’s birthplace, which was also reused as an exhibition venue for engravings, drawings, paintings and books.

Numerous plaster casts are presented in this part of the exhibition itinerary, among them no less than two relating to the sculpture Sleeping Endymion, preserved at Chatsworth House in England. In fact, both the model used to make the statue and the cast that was taken from it appear on display, so that the public can grasp the differences between the products of the different stages of the creative work.

|

| Martino De Boni (?), Antonio Canova shows the drawing of Hercules and Lica to the Torlonia family (1805-1806; oil on canvas, 30 �? 36.7 cm; Rome, Museo di Roma, inv. Dep GAA 130, FN 17690) |

|

| Pietro Fontana, Hercules and Lica (from behind) (1811-1812; etching and burin, 527 �? 391 mm; Rome, Museo di Roma, inv. MR 16340) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Bust of Antonio Canova (1832; marble, 50.5 �? 23 �? 21 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums, inv. 15935) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Sleeping Endymion (1819; plaster, 183 �? 85 �? 95 cm; Possagno, Gypsotheca and Museo Antonio Canova). © Fondazione Canova onlus - Gypsotheca and Museo Antonio Canova | Internal Photographic Archive, Photo by Lino Zanesco |

Canova proceeded from a clay sketch, often anticipated by drawings or paintings, and then made one of the size that the statue would be; on the latter his collaborators poured plaster to obtain the form, which, once the clay had been removed and destroyed, was filled with liquid plaster, and when this had solidified, opened and removed. Once this process was completed, the model was obtained, onto which bronze pegs were fixed, which in fact we see on one of the two plaster casts of theSleeping Endymion (and on many others on display in the exhibition), and which constituted fundamental points of reference reported, with squares and compasses, on the marble block. The working of the marble was entrusted by Canova to collaborators who at the end left, with respect to the plaster, a thin layer of extra material; on this the master intervened, who, even making changes with respect to the model, gave “the last coat” finishing the work. One of the testimonies we have about this procedure of the artist is provided by Leopoldo Cicognara, who in his Biography of Antonio Canova writes: “And it must be said that the practices that he himself gradually introduced were not in use then, that is, of availing himself of the subordinate arms to digross the marbles, down to the last layer of surface [...] the last hand was always, however by him put to his works, bringing with it the stones, to that softness, that sweetness of outline, that fineness of expression, which has been vainly sought and is hardly to be found in the works of his contemporaries.”

Subsequently, it was possible to draw from the sculpture forms used to produce, still by casting plaster, casts. These, then, could be obtained either from the starting model or from the finished work.

The plaster casts Hebe and Cupid and Psyche standing from the statues preserved in the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and in St. Petersburg in the Hermitage, respectively, are splendid. In particular theHebe, together with the cast exhibited here taken from the marble sculpture Maddalena penitente also on display in the exhibition and already mentioned, was made in Canova’s studio at Papafava’s request in the same year, 1806, in which the plaster casts of Perseus Triumphant and Creugante were made. As Pavanello notes in the catalog entry on the cast of Hebe, "one would say that, once Canova’s relationship with Antiquity was highlighted with emblematic works in the two pairs Creugante/Perseo-GladiatoreBorghese/Apollodel Belvedere, there was a desire to witness in Papafava’s home the dimension of grace - in Hebe - and of the pathetic - in the Penitent Magdalene."

Moreover, anticipating this section of the exhibition itinerary is a room entirely dedicated to the drawings of the Venetian sculptor; in this way, the public is also allowed to come into contact with the initial steps of the creative process: meditation on a given theme and the conception of the subject.

Mention has already been made of the relevance of Canova’s relationship with Rome, the place where he spent so much of his life, trained, and consolidated his career, and of the fact that the exhibition has chosen to place him at the center of the narrative. One could not, therefore, fail to deal with such a radical upheaval as the French occupation of the city, which had a considerable impact on the sculptor, who was, moreover, staunchly anti-Jacobin. Thus, along the way we encounter several drawings and engravings recounting the events that led to the first occupation, which began in February 1798, and the subsequent birth of the Roman Republic; among the etchings, one by Antonio Poggioli depicts the signing of the Treaty of Tolentino, while another executed by Alessandro Mochetti portrays Pius VI as he leaves Rome escorted by French Dragoons. To these events the Venetian sculptor reacted by leaving in May of the same year, only to return in 1799, following the fall of the Republic at the hands of the Bourbon army.

However later, when Rome was annexed to the French Empire in 1809 and Pope Pius VII, like his predecessor, was also exiled, Canova did not leave the city, he stayed and collaborated with the new regime. The following year he was elected Prince of the Academy of St. Luke, and on display is the letter in which, from Florence, reached by the news of his appointment, he thanked the members of the institute for the honor bestowed on him.

Also on display is the statute enacted in 1812, bearing the signatures of Canova and Napoleon, by which the Academy was endowed with a didactic order, and invested with powers in the excavation, restoration and protection of monuments.

Already in 1802 Canova had been entrusted with a major role by Pius VII, of whom a year later he made the portrait bust displayed in the exhibition and coming from the Promoteca Capitolina. The pontiff, in fact, had appointed Antonio Inspector of Fine Arts in Rome and the Papal States, with vast powers over all works of art, including vetoing their export.

Immediately after his appointment, the artist purchased eighty ancient cippi, including one visible here, from the Giustiniani collection out of his own pocket, to make gifts of them to papal museums, thus replenishing their collections. But the most remarkable feat that Canova accomplished for the artistic heritage of Rome, and not only, was the recovery of part of the works taken from France by the Treaty of Tolentino.

The sculptor, in 1815, after the fall of the Napoleonic empire, was sent to Paris (where he had already been to portray Napoleon and other members of the imperial house) at the suggestion of Cardinal Consalvi, to whom in the 1920s Bertel Thorvaldsen executed the marble portrait on display in the exhibition; he returned after four months, with about a third of what had been taken by the French, still more than had been permissible to hope for.

On another occasion, however, Canova failed in his intentions. In fact, in 1820, despite his and Chamberlain Bartolomeo Pacca ’s strenuous opposition (who would shortly thereafter promulgate a very important edict protecting the papal artistic heritage), Pius VII authorized the sale of the antique sculpture known as the Fauno Barberini to the Emperor of Austria Francis I, who purchased it for his brother-in-law Ludovic I. So the ancient statue left Rome, and to this day it is still preserved at the Glyptothek in Munich. However, fortunately, several casts were taken from the sculpture before it was exported, and one of these, made in the early 19th century and coming from the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna, is presented in the exhibition itinerary. Next to the plaster cast we also see a marble bust of Cardinal Pacca made by sculptor Francesco Romano Laboureur, on loan from the Accademia Nazionale di San Luca.

As we approach the end of the exhibition we encounter a room devoted to Canova’s last labors. Prominent here is a plaster cast taken in 1818 from the Cenotaph of the last Stuarts, depicting one of the two splendid funerary geniuses so admired by Stendhal, which after the sculptor’s death were censured by order of Leo XII, along with the other nude from the funeral monument to Clement XIII Rezzonico, with the application of robes, later fortunately removed.

We also see two models of what should have been and never was, the gigantic sculpture

of Religion with which Canova would have wanted to pay homage to the return of Pius VII to Rome after the fall of Napoleon. The work, a filiation of the statue already executed for the Rezzonico mausoleum, which in the artist’s intentions should have reached eight meters and been placed in St. Peter’s, was opposed by the canons of the Basilica who opposed its placement in the building, and it was never realized, so that Canova diverted the funds he had allocated for the statue to the construction of the Temple of Possagno.

Finally, before reaching the piece that emphatically concludes the exhibition, the Dancer with her hands on her hips, one can admire some photographs with which Mimmo Jodice, in the 1990s, portrayed Canova’s most iconic works. Truly an interesting choice to present these caressing shots of the Neapolitan artist, capable of delivering to our observation reworked sculptures, recreated with imagination, thanks to which using Jodice’s own words “the temples, the streets and the statues themselves come alive, time no longer exists, past and present become one.”

|

| Antonio Canova, Hebe (1806; plaster, 160 �? 54 �? 60 cm; Padua, Palazzo Papafava, private collection) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Cupid and Psyche standing (plaster, 148 �? 68 �? 65 cm; Veneto Banca spa in L.C.A.). Photo by Andrea Paris |

|

| Bertel Thorvaldsen, Bust of Cardinal Ercole Consalvi (1824; plaster, 76 �? 60 �? 34 cm; Rome, Museo di Roma, inv. MR 43584) |

|

| Roman Former, Fauno Barberini (before 1811; plaster, 200 �? 130 �? 130 cm; Bologna, Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna - Patrimonio Storico). Photo by Luca Marzocchi |

|

| Antonio Canova, Monument to the Last Stuarts (1816-1817; plaster, 69 �? 58 �? 12 cm; Possagno, Gypsotheca and Museo Antonio Canova, inv. 255) |

|

| Antonio Canova, The Religion (1814-1815; plaster, 110 �? 116 �? 55 cmM Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Dancer hands on hips (1806-1812; marble, 179 x 76 x 67 cm; St. Petersburg, The State Hermitage). © The State Hermitage Museum, 2019, Photo by Alexander Lavrentyev |

In the last room, the Dancer, also from the Hermitage like theCupid and also placed on a rotating pedestal, is reflected in the mirrors that cover the walls of the room.

The sculpture was executed between 1805 and 1812 on a commission from Napoleon’s first wife, Joséphine de Beauharnais, upon whose death it was acquired by Tsar Alexander I, and represents the first in a series of three figures of ballerinas, the result of the artist’s interest in a subject that is an expression par excellence of grace, and also addressed in drawings and tempera paintings in which there is a remarkable variety of movements and dance poses.

Exhibited at the Paris Salon in the year of its completion, it was, according to the testimony of Joséphine herself, a resounding success.

In his Memoirs of Antonio Canova, the sculptor Antonio D’Este, of whom we have spoken, observes that if the Venetian master had not moved from his hometown, “he would have become but a communal artist, notwithstanding the awakenedness of his wits” because “the magnificences of Rome, which magnified the genius of Raphael, Michelangiolo and other classics, elevated and sublimated the mind of Canova also.” At a time of great interest in the figure of this artist, evidenced by the simultaneous creation of two other major exhibitions dedicated to him in Milan and the previous exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, it was therefore necessary for an exhibition to finally recount, in Rome, the Rome of Canova. And in doing so, the exhibition presents a very rich and well-structured narrative itinerary, supported by clear exhibition panels (and for those who wish to delve deeper, also by an audioguide that can be purchased at the entrance), which effectively outlines the professional figure of an artist whose critical reappraisal is a fairly recent affair.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.