by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 04/08/2021

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Carte Blanche. A New History. 49 artists x 49 covers" in Massa, Guadagnucci Civic Museum, through Aug. 29, 2021.

"The constraints of confinement have led each of us to question our lifestyles, our true needs, our aspirations, repressed in those who suffer a closed condition between home and work, forgotten in those who enjoy a less enslaved life, and masked generally by the alienation of the everyday or removed in Pascolian divertissement, which distracts us from the real problems of our human condition." Edgar Morin wrote this in the first of his 15 Lectures of the Coronavirus, published as the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic was beginning to take shape and again convince governments halfway around the world that locking people in their homes for longer or shorter periods of time was the best way to deal with the problem. Unprecedented times they call them in Anglo-Saxon countries: a moment that is unprecedented. And as is the case with all moments that are unprecedented, the flow of emotions through it is stormy, violent, contradictory, uneasy and disturbing, perhaps even more unpredictable than the course of the waves of the epidemic. It is a whirlwind that has swept through art as well, with at least a couple of positive consequences: it has unleashed a moment of luminous and widespread creative euphoria (as is typical of moments of crisis, after all) and it has taken the form of a sort of rappel à l’ordre, in the guise of a concrete, tangible and immediate unit of measurement with which artists have been forced to confront themselves.

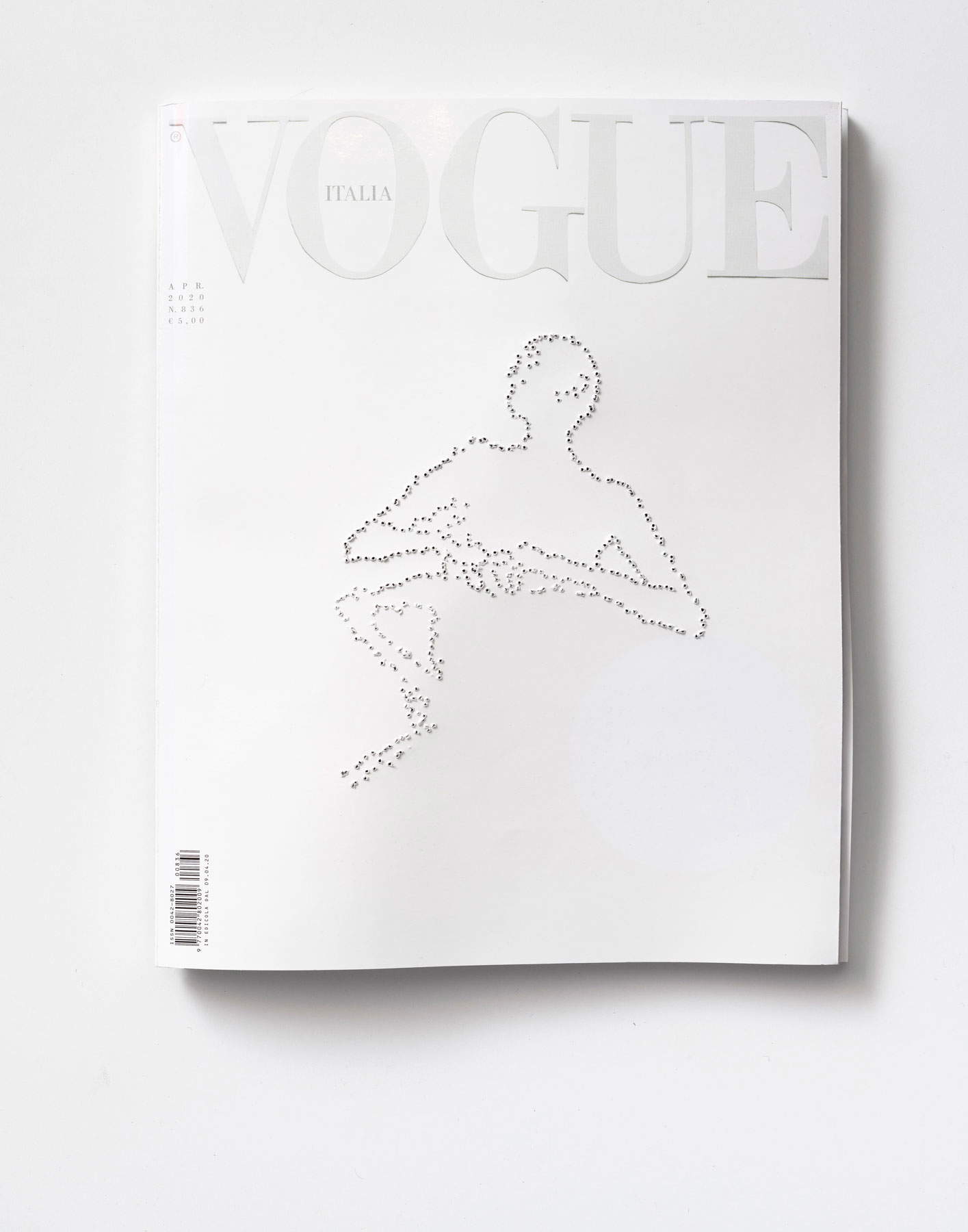

To determine whether original results will come out of it and to see how it will affect the course of art history is too early: at the moment one can probably only chronicle it. It is true for those who write about art, it is also true to a certain extent for those who produce art. But bringing contemporary art back to an urgent and pressing dimension is already an achievement: not to document, for that is not what art is for, and that is not what it was born for. If art, remembering Gastone Novelli, is the way in which human beings orient themselves in the world, then more than ever it is needed in situations where a dazed and lost humanity feels the need for tools to facilitate its navigation. Valentina Ciarallo must therefore be credited with having fabricated a sort of small compass that offers, in the small of the contribution that the visual arts can make, the possibility of understanding which cardinal points Italian artists have oriented themselves toward in the first months of the pandemic. The Roman curator had the idea of having forty-nine artists fill the White Issue of Vogue Italia, that is, the April 2020 issue that came out with a completely white cover to give a sense of the bewilderment in the face of the outbreak of the epidemic that shocked the world.

It is well known that readers of the Italian edition of Vogue have always been accustomed to colorful, extravagant covers, updated with respect to the latest trends. It was a habit that had been repeated nonstop since 1962: never had a cover been empty in almost sixty years of publication. Emptiness thus became an allegory of bewilderment. An allegory, however, that Ciarallo, a sort of fiftieth artist as many noted at the presentation of the exhibition, overturned with diligence and resourcefulness: a void can also be filled, a void can represent a beginning, a more or less circumscribed white space is almost always the beginning of a work of art. The results of the initiative, which naturally had the full support of Vogue, can be seen at the exhibition Carta Bianca. A New History at the Guadagnucci Museum in Massa (although it is already known that the exhibition will then tour), until August 29: the forty-nine covers are on display in the halls of the museum, which, moreover, with this review, inaugurates the new course under the aegis of the new director Cinzia Compalati, capable at the first stroke of bringing quality contemporary art back to an Apuan public museum, after too long of absence and discouragement. For this reason, too, the exhibition is worth a visit.

|

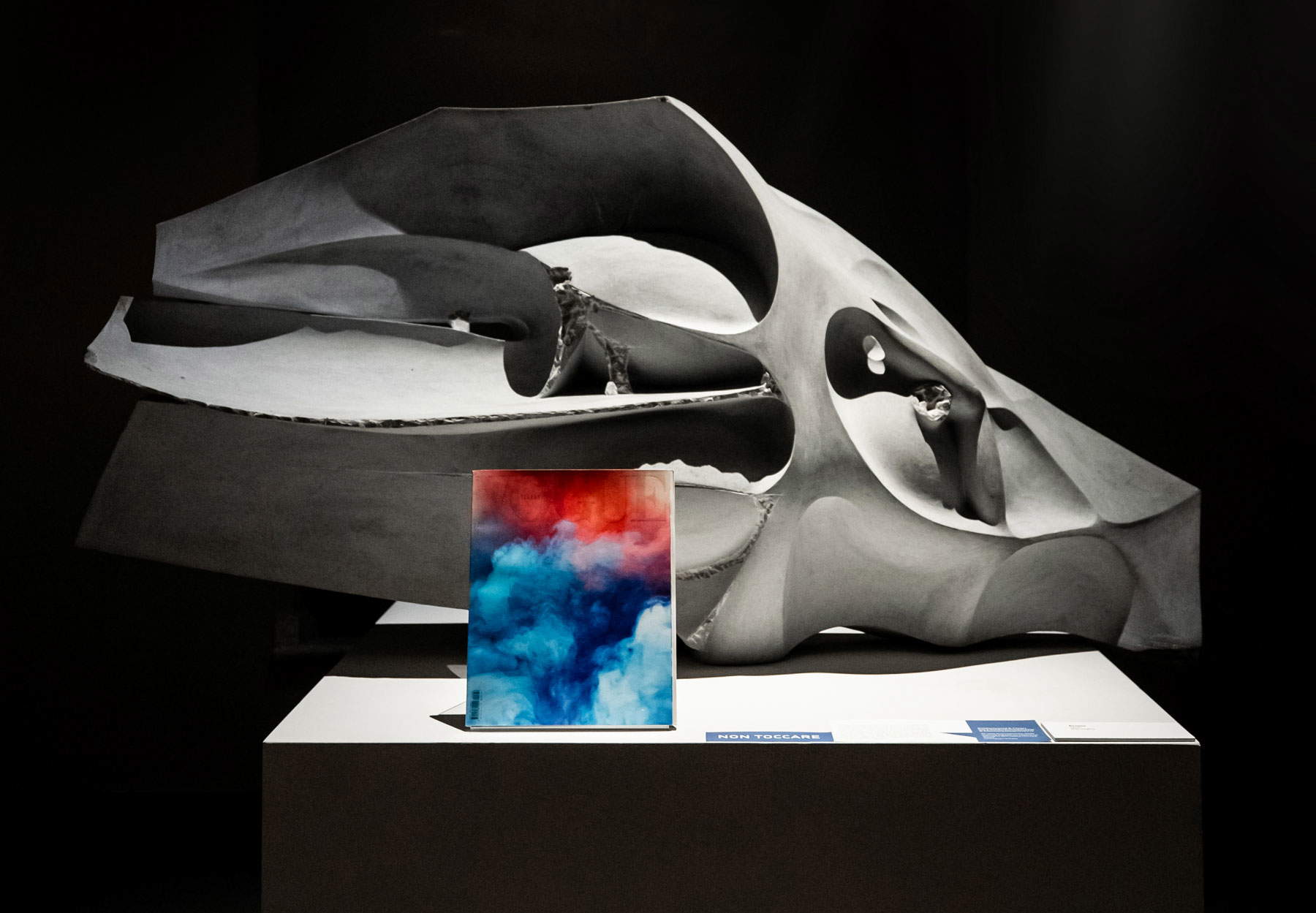

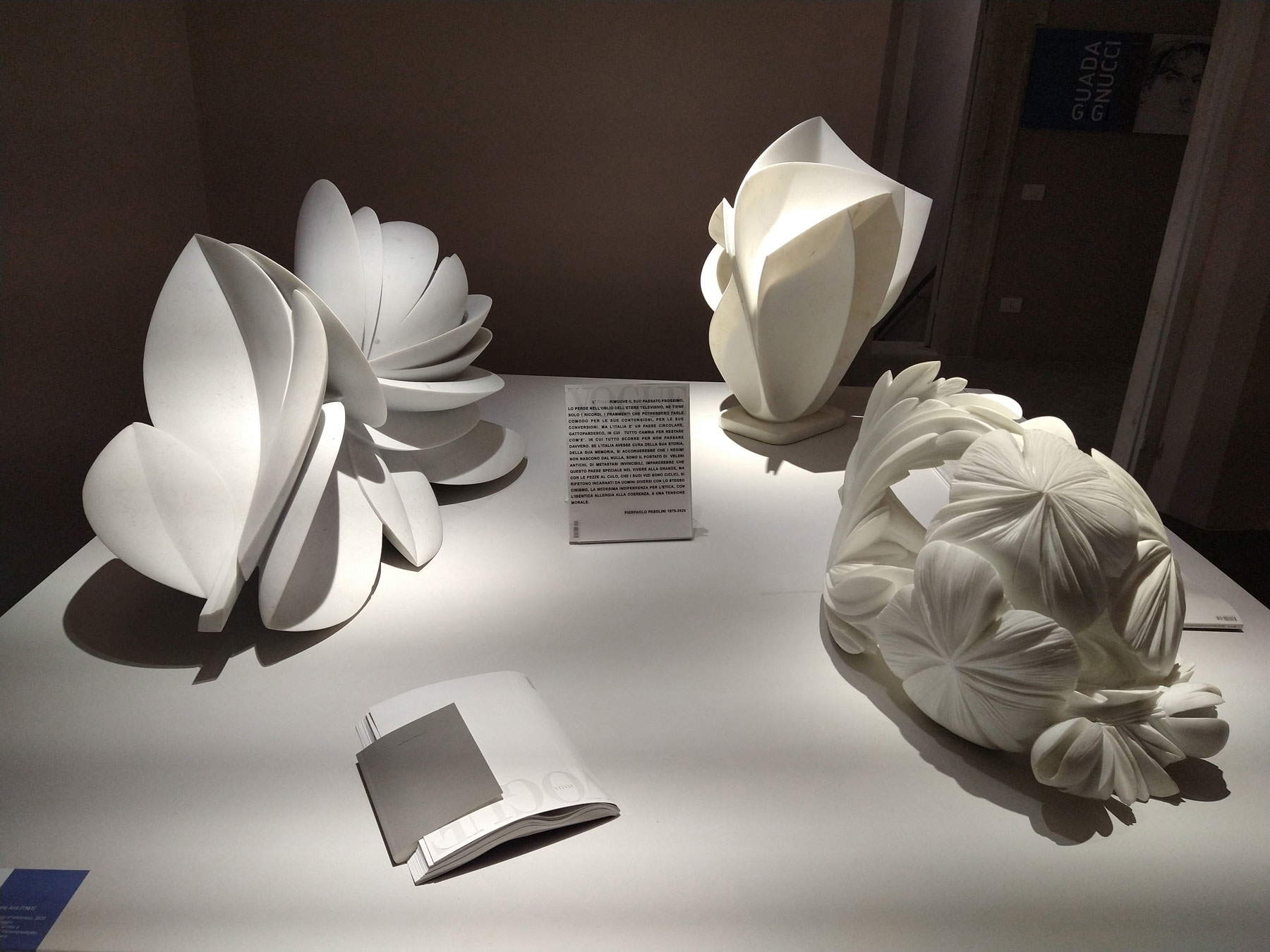

| View of the exhibition Carta Bianca. A New History. Photo by Serena Rossi |

|

| View of the exhibition Carta Bianca. A New History. |

|

| View of the exhibition Carta Bianca. A new story |

|

| View of the exhibition Carta Bianca. A new history |

|

| View of the exhibition Carta Bianca.A New History. |

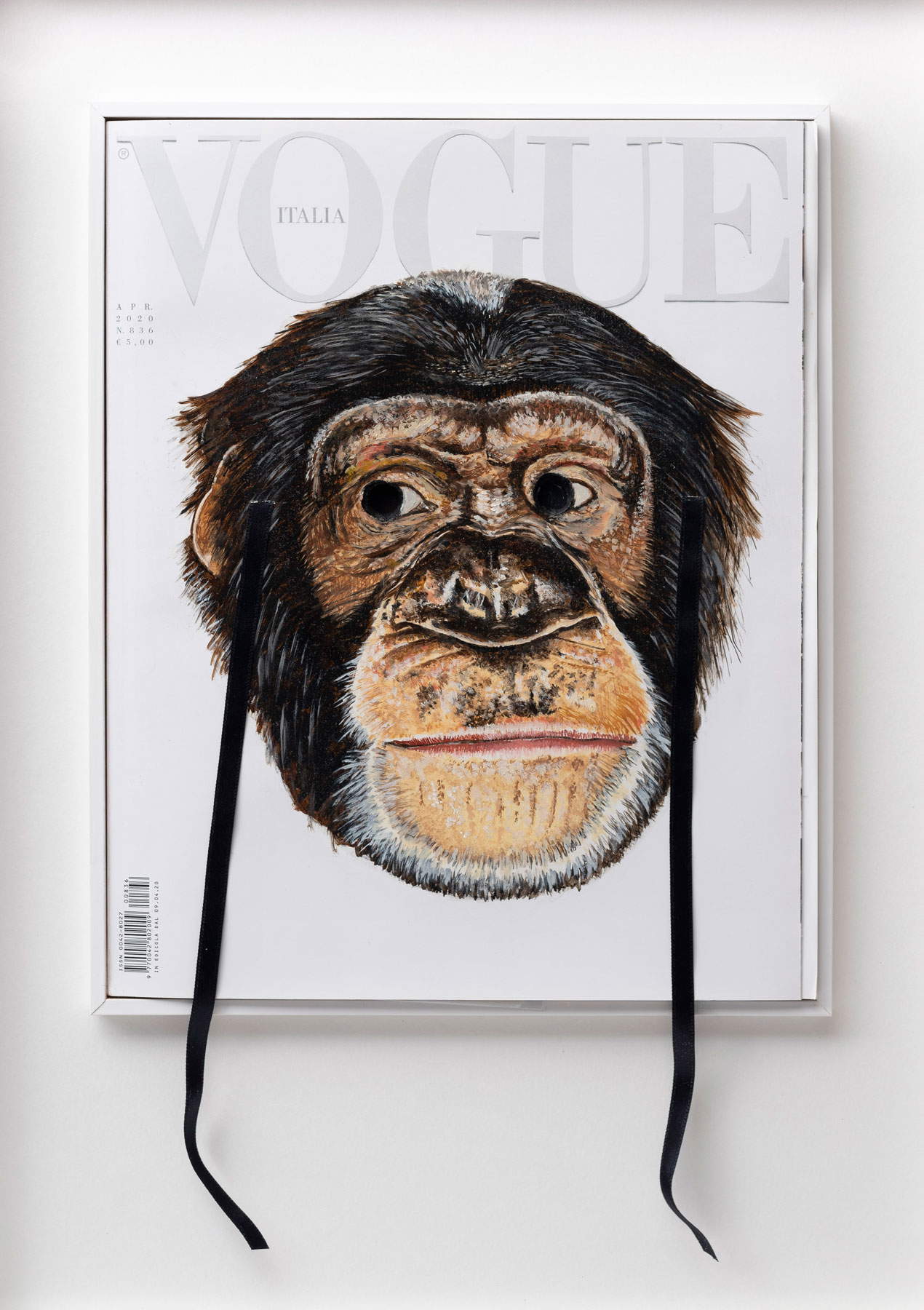

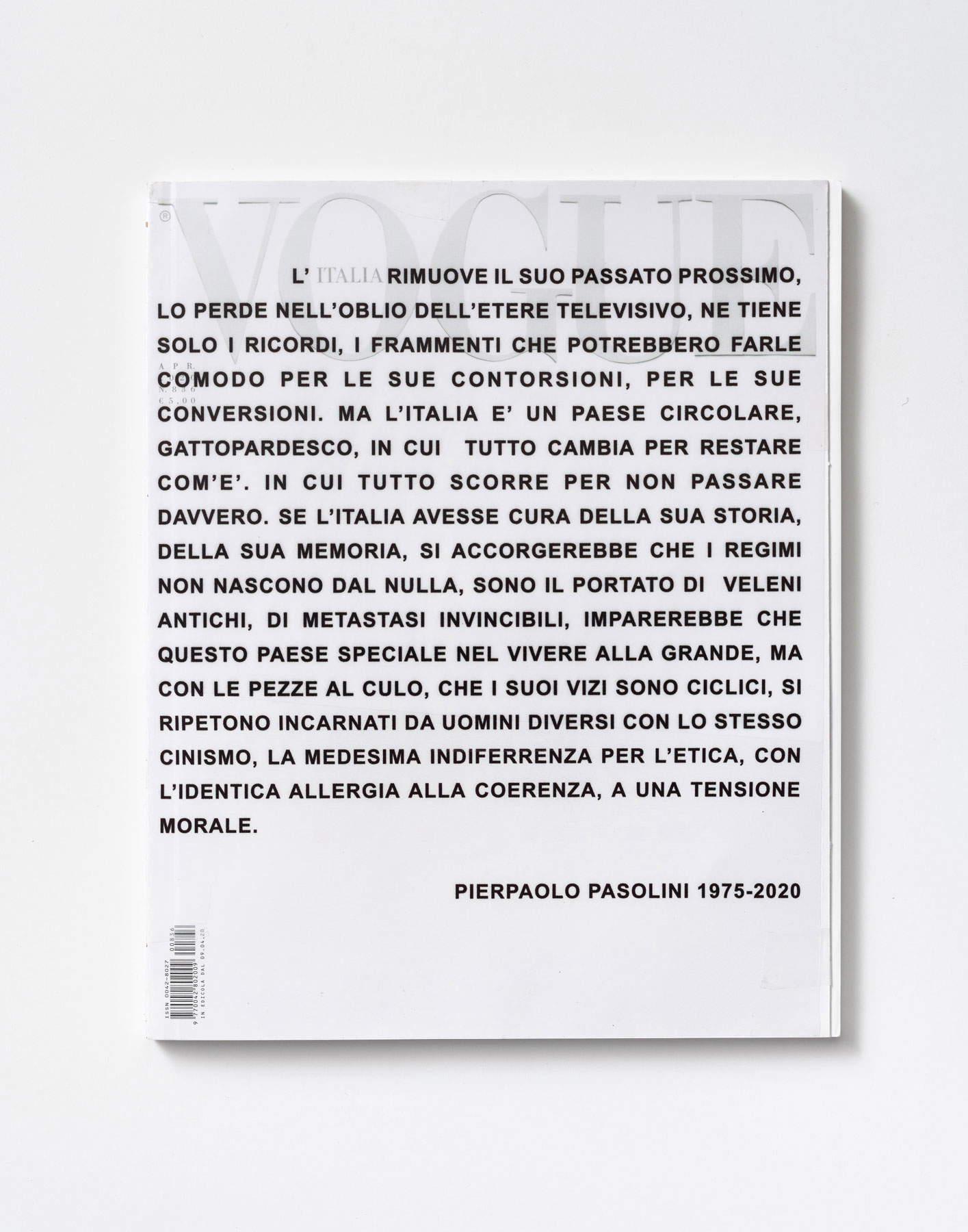

The “new story” alluded to in the title of the exhibition is the one that the forty-nine artists write on the front page of Vogue: as is the case with all group shows, there are those who interpret their role in a more passionate and engaging way and there are those who come across as more tired or rhetorical, but the result overall is more than positive. Welcoming the visitor are, paired, 7.62 x 63 mm by Flavio Favelli and #836 A by Giovanni De Angelis: the first work is conceptually more complex, with its reference to another tragedy (that of Ustica), and the second is more immediate, resolving itself in a clean cut in the center of the magazine, a luminous red line that is almost a wound from which, however, rebirth sprouts. Mauro Di Silvestre ’s friendly monkey(I wanna be like you!) is loaded with meanings that refer to the forgotten others (“what does an animal feel about living on this planet and what would the chimpanzee think of our progress,” the artist wonders), and introduces La pittura precede la natura by Matteo Fato, a reflection on art as mímesis developing a thought by the musical philologist Gianni Garrera. We continue to the next room where Francesco Arena ’s untitled cover exploits the word “Italy” inside the words “Vogue” to present a quote by Pasolini from 1975, chosen because of its disconcerting topicality: “Italy removes its near past, loses it in the oblivion of the television ether, keeps only its memories, the fragments that might suit her contortions, her conversions. But Italy is a circular, catlike country, in which everything changes to remain as it is. In which everything flows in order not to really pass.” Arena’s work is flanked by Mario Airò’s The elegy of whiteness, which celebrates whiteness as an open form and symbol of birth and death, and a collage by Marina Paris, Numero 836, which pastes on a cover a group photo from 1951 probably to emphasize the differences between the Italians of today and those of the 1950s that refounded the country.

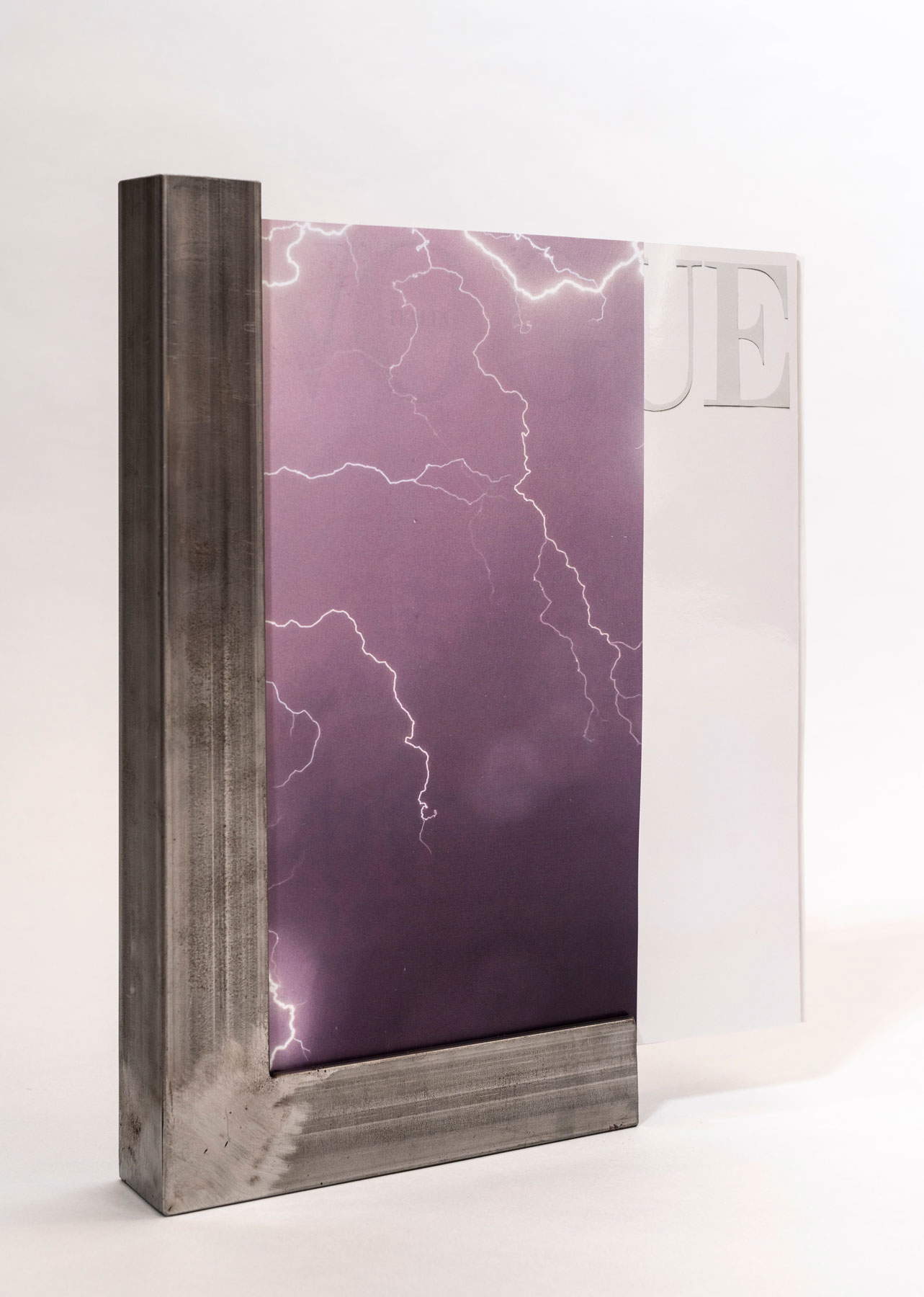

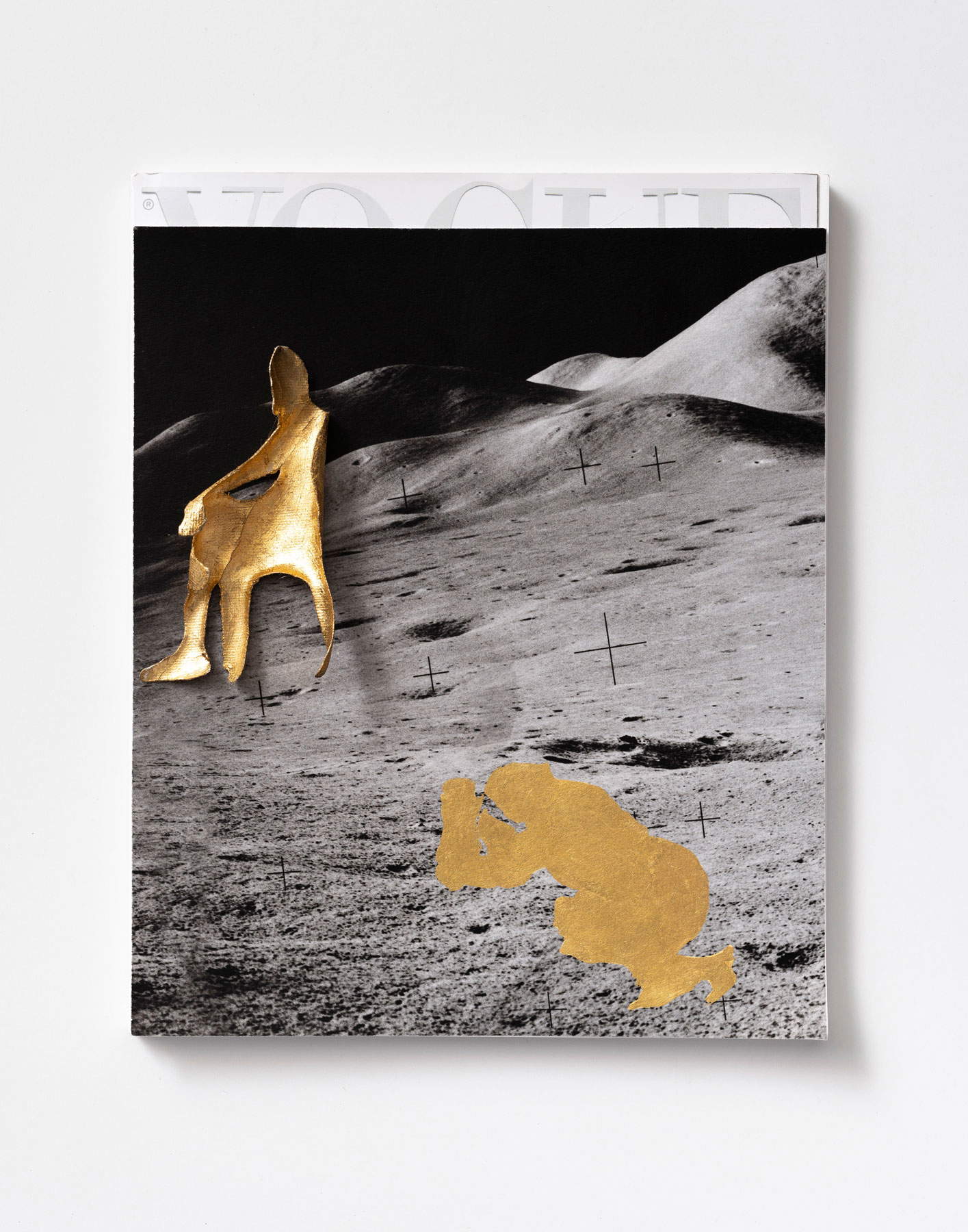

Stefano Arienti pierces the Giorgio Armani advertisement on the back cover, achieving a transfiguration: no longer a self-confident model, but a woman who seems almost to ask for help, trapped between the pages. Minimal language for Elisabetta Benassi who further puts white on white by deleting “VOG” to let “EU” remain with an obvious reference to the European Union and its role during the pandemic. Decidedly more interesting is the work Allunati by Rä di Martino, who stages on the cover of Vogue a re-enactment of the conquest of the moon, an experience that, according to the artist, raprpesentated (and still represents) the challenge to the unknown and the supremacy of reason over chaos, other themes that have entered our daily lives. Not far away, Windows by Patrick Tuttofuoco reasons about the future by transforming the cover of Vogue into a refined sculpture and imagining it as an open window on a threatening sky, ripped open, however, by the lightning bolt of art, creativity, and imagination. A collage also for Giuseppe Pietroniro, who plays on the perception of forms through optical illusion, while Diego Miguel Mirabella is inspired by Islamic mosaics to show, through openings on the cover, the contents of the magazine (the reference is to how we used to look at the world during confinement: through our windows, but also through the narrow and oppressive openings of the media).

|

| Mauro Di Silvestre, I WANNA BE LIKE YOU! (2020; oil and silk ribbons on cover). Courtesy the artist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Giovanni De Angelis, #836 A (2020; led light on cover). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Francesco Arena, Untitled (2020; print on clear sticker on cover). Courtesy of the artist, photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Stefano Arienti, Untitled (2020; perforation on cover). Courtesy the artist and Studio SALES di Norberto Ruggeri, Rome. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Patrick Tuttofuoco, Windows (2020; steel profile, adhesive photograph on cover). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Rä di Martino, Allunati (2020; photographic print and canvas cutouts on cover). Courtesy lartist Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Matteo Nasini, Tighten Me That We Go (2020; acrylic wool and cotton threads on Vogue). Courtesy lartist and Clima Gallery, Milan. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Goldschmied & Chiari, Dawn of a Sunset (2020; digital print on cover, detail of the work Untitled Views). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

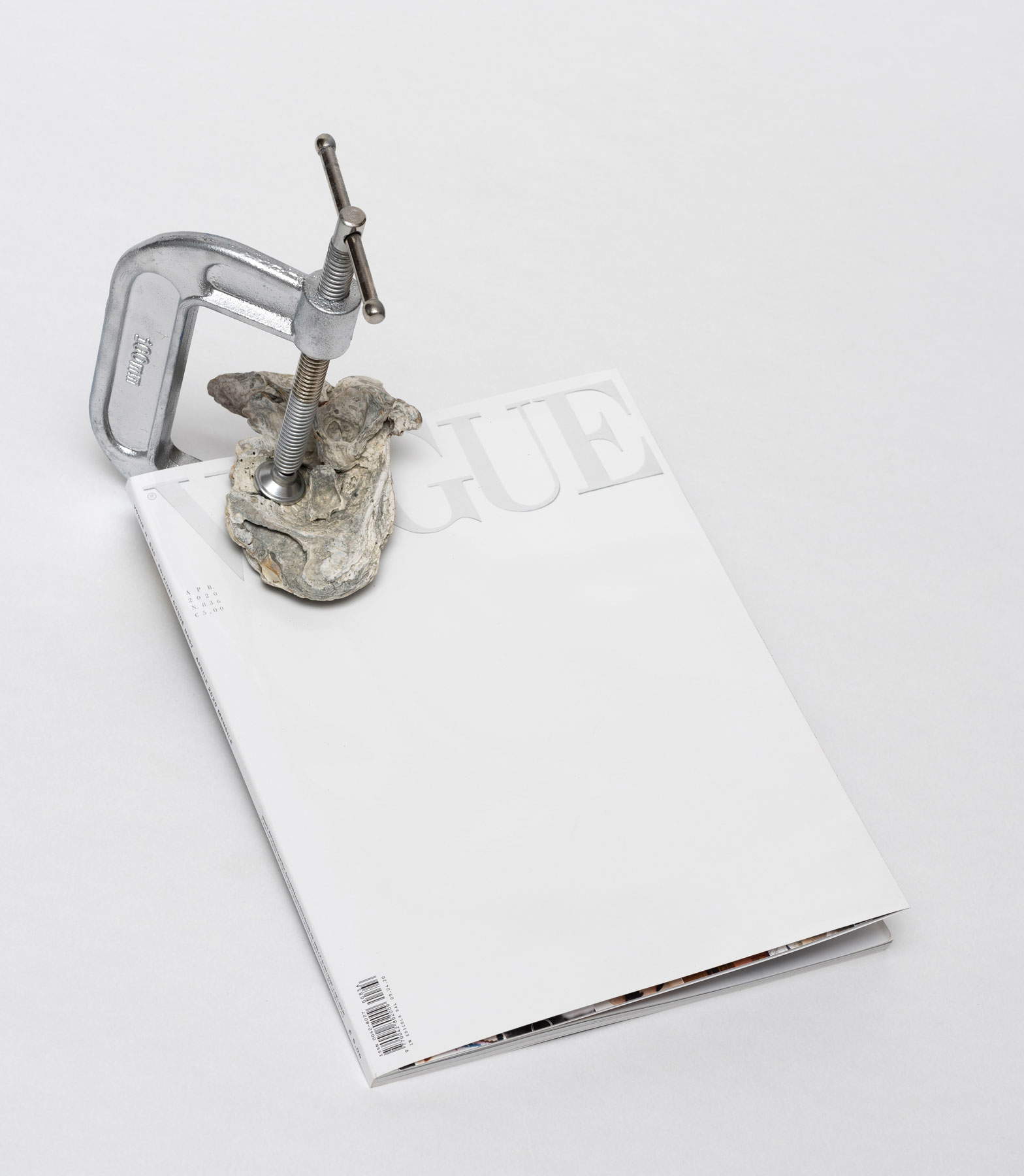

| Federica Di Carlo, Je suis la Vague (2020; French fossil shell, silver iron clamp on Vogue). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

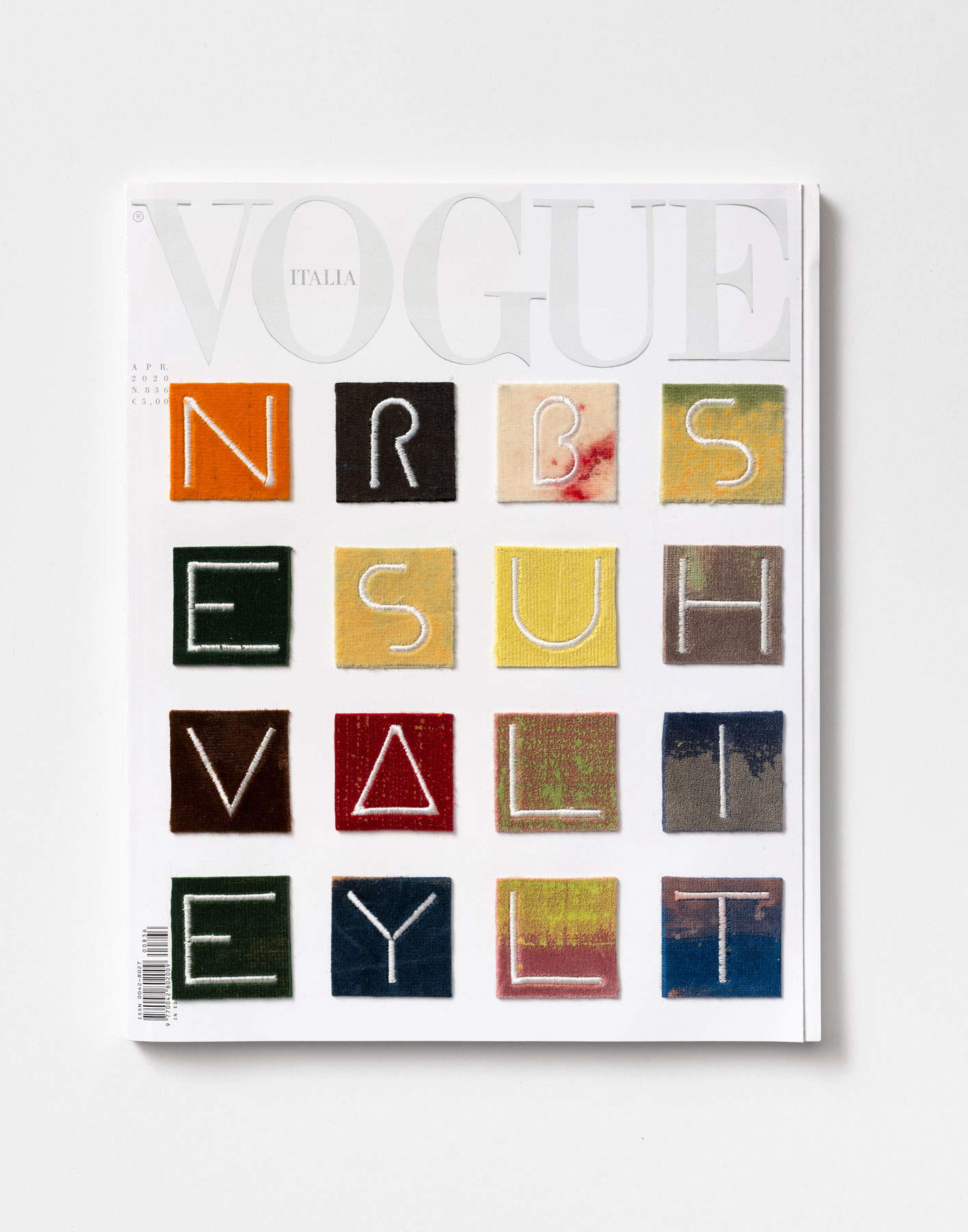

| Riccardo Beretta, Never Say Bullshit (2020; embroidery on painted velvet on cover, sponsored by Anna Monti). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

Squeeze Me We’re Going by Matteo Nasini is one of the most poetic interpretations in the exhibition: the magazine becomes a metaphor for reality and is rolled up because we do not know what will happen in the future, and the hope for rebirth is symbolized by the gold combined with the black of the bleak present. Next door, here appears Saving Time, a dense work by Letizia Cariello to whom the white cover of Vogue reminded her of a cloud-covered sky, which led her to a dreamlike dimension expressed through the circle of numbers: an allusion to a wounded and yet stitched-up calendar, since nature destroys and rebuilds by allowing time to flow circularly. The one who dreams of the sea is Federica Di Carlo, who with Je suis la vague fixes a seashell to the cover of Vogue by means of a vise: her desire during confinement was to return to the sea, an instinctive desire for reunion with a primordial element. But also, the curator points out, “a reflection on how to loosen the grip,” since “global frenzy becomes a vice that must be lightened to prevent the shell from crumbling and us with it.” Maritime is also the work of Salvatore Arancio who proposes another shell: a collage that transports us back to the dimension of nature. Also with auditory sensations: the podcast Arancio created for the work (each artist was invited to produce one, so there are those who explained the work, those who recited excerpts or those who, like Arancio, created sound settings for their work, and they are all downloadable from the museum’s website) contains the sounds of a day on a lonely beach.

If the duo Invernomuto places an eerie Terminator on the cover of Vogue, more relaxing appears In the dawn of a sunset by the other duo in the exhibition, Goldschmied & Chiari, who offer one of their classic, colorful and highly regarded works made of clouds spewed from smoke bombs, with the chromatics here inspired by what Calvino called “the hour in which they lose the consistency of shadow that accompanied them in the night and gradually regain their colors,” the moment of dawn, “the hour in which one is least sure of the existence of the world.” We end our visit on the second floor with Riccardo Beretta ’s Never Say Bullshit (a curious and well-executed encounter between Alighiero Boetti and Maurizio Cattelan), with the artificial intelligence of V.I.P. (Vogue Intelligent Pro) by Donato Piccolo which, by means of software, analyzes the contents of Vogue to create signs to be projected on the wall, thus opening up to new perceptions but without losing contact with a reality embodied by the still-wrapped cover (a reality that is, however, ready to generate new life), and with the third duo, Vedovamazzei, which, in a conceptual operation, closes Vogue with a padlock.

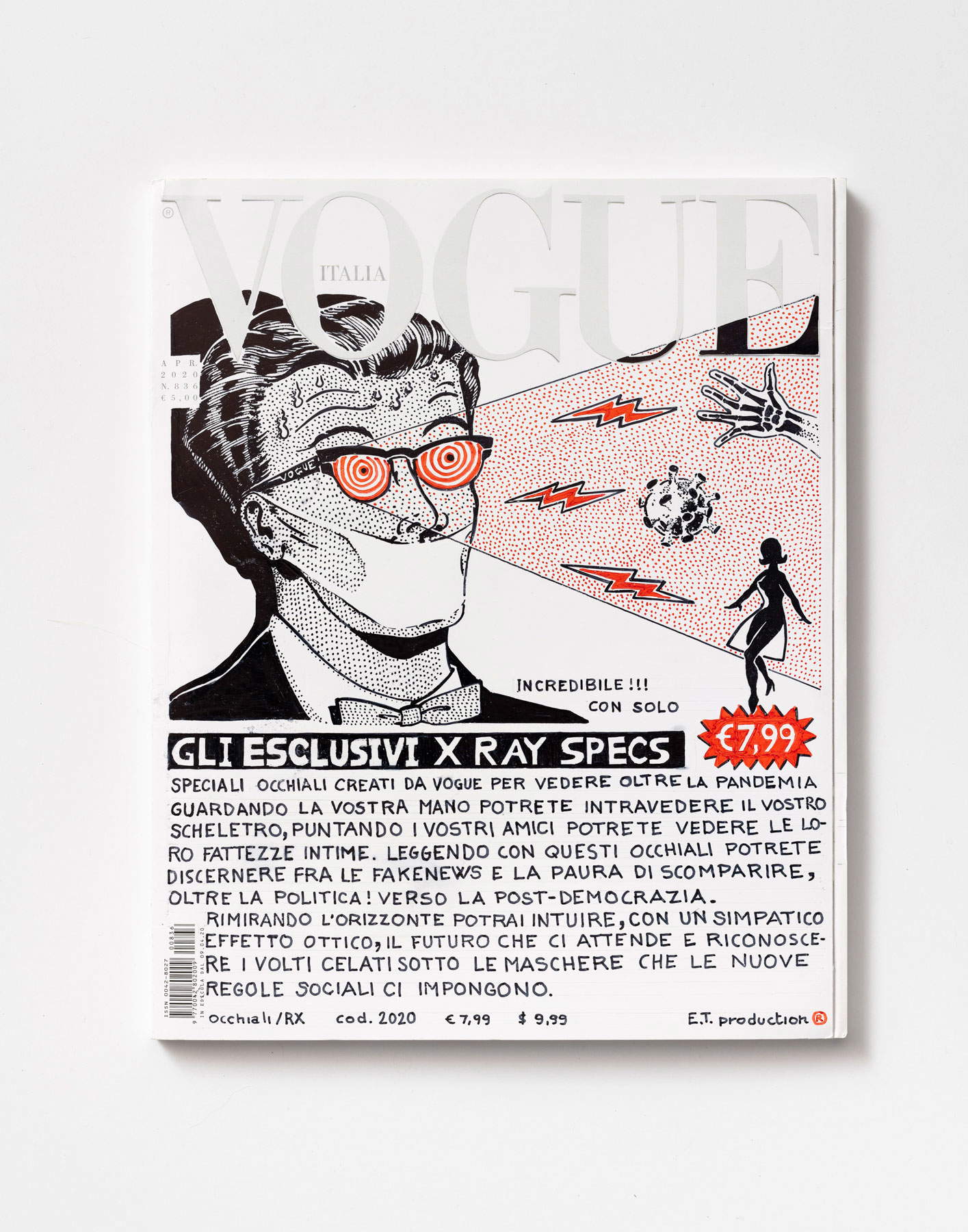

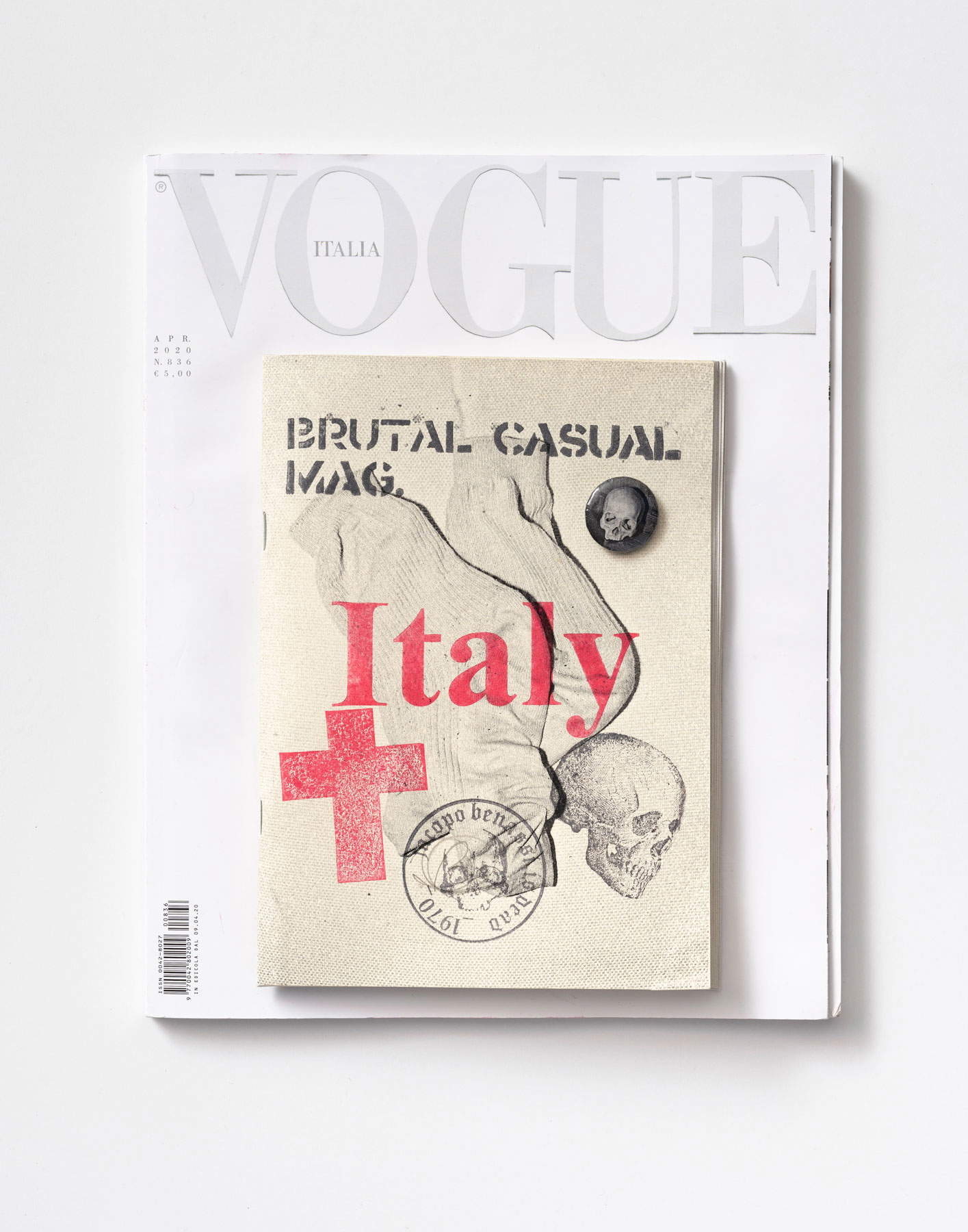

One descends to the lower floor where one first meets Eugenio Tibaldi and his See Beyond, which reworks illustrations from the 1950s to reflect on a popular gadget of the time, X-ray glasses, which no one bought (who ever thought they would work?) but which, in a contemporaneity in which everyone deludes themselves into thinking they know, become the means to bring us back to reality (experiencing the burn of shame after verifying the groundlessness of one’s theories is a kind of good educational practice, the artist seems to suggest). Giuseppe Stampone also talks about education with Global Education, a pen drawing intended to emphasize the need to return to “an ethical commitment even before an aesthetic one, to political activism in the everyday and to the urgent need to build connective, cognitive, tactile and global structures,” Ciarallo writes. Next, Lamberto Teotino uses an old photo recovered from the web to meditate on the value of the concept of “family,” while Giovanni Kronenberg applies gold leaf to the bottom tab of the cover of Vogue to give it a sculptural dimension and thus open it to the outside world. Among the best works in the exhibition, Fabrizio Cotognini ’s The shadow of the soul transforms Vogue into an ancient book using gold leaf, and also incorporating original engravings from the 19th century depicting monstrous characters and animals into the work to compose a kind of allegory of the present time with expressive means that draw on tradition. Gianni Politi covers Vogue with a metallic paint to create an inscription where he states that he always feels quarantined(I have always been in quarantine), and next to him Jacopo Benassi transforms Vogue into another magazine, Brutal Casual, which collects the artist’s “daily brutality,” including junk food dinners, sex, alcoholic evenings and many other moments of which we all or almost all have felt nostalgic during various confinements. The lockdown sampler is evoked by Marco Raparelli, who in List for reboot lists a series of objects that helped him cope with forced segregation: computers, pens, pencils, music, books, brains, hearts, eyes. Next, Stanislao Di Giugno, with Sfregio #9, etches the cover to search for new shapes and colors in the depths of the magazine.

|

| Eugenio Tibaldi, See beyond (2020; permanent marker on cover). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Jacopo Benassi, Brutal Casual vs. Vogue (2020; mixed media on cover). Courtesy lartist and Galleria Francesca Minini, Milan. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

| Fabrizio Cotognini, The shadow of the soul (2020; gold leaf, ink, mylar and original 19th-century engraving on cover). Courtesy lartist and Prometeo Gallery di Ida Pisani, Milan. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

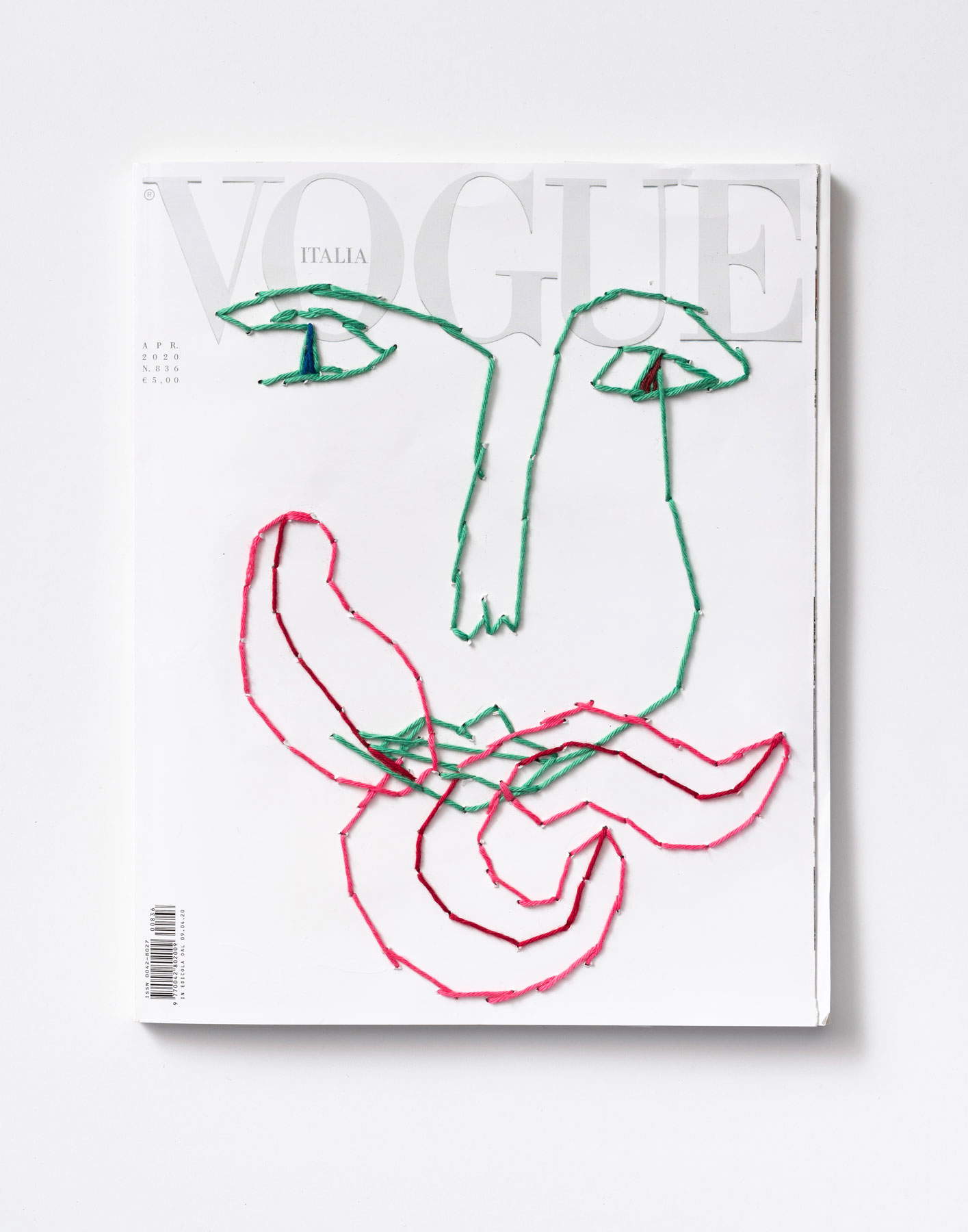

| Sissi, Portrait in Bloom (2020; embroidery on cover, cotton thread). Courtesy lartist and Galleria Tiziana Di Caro, Naples. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

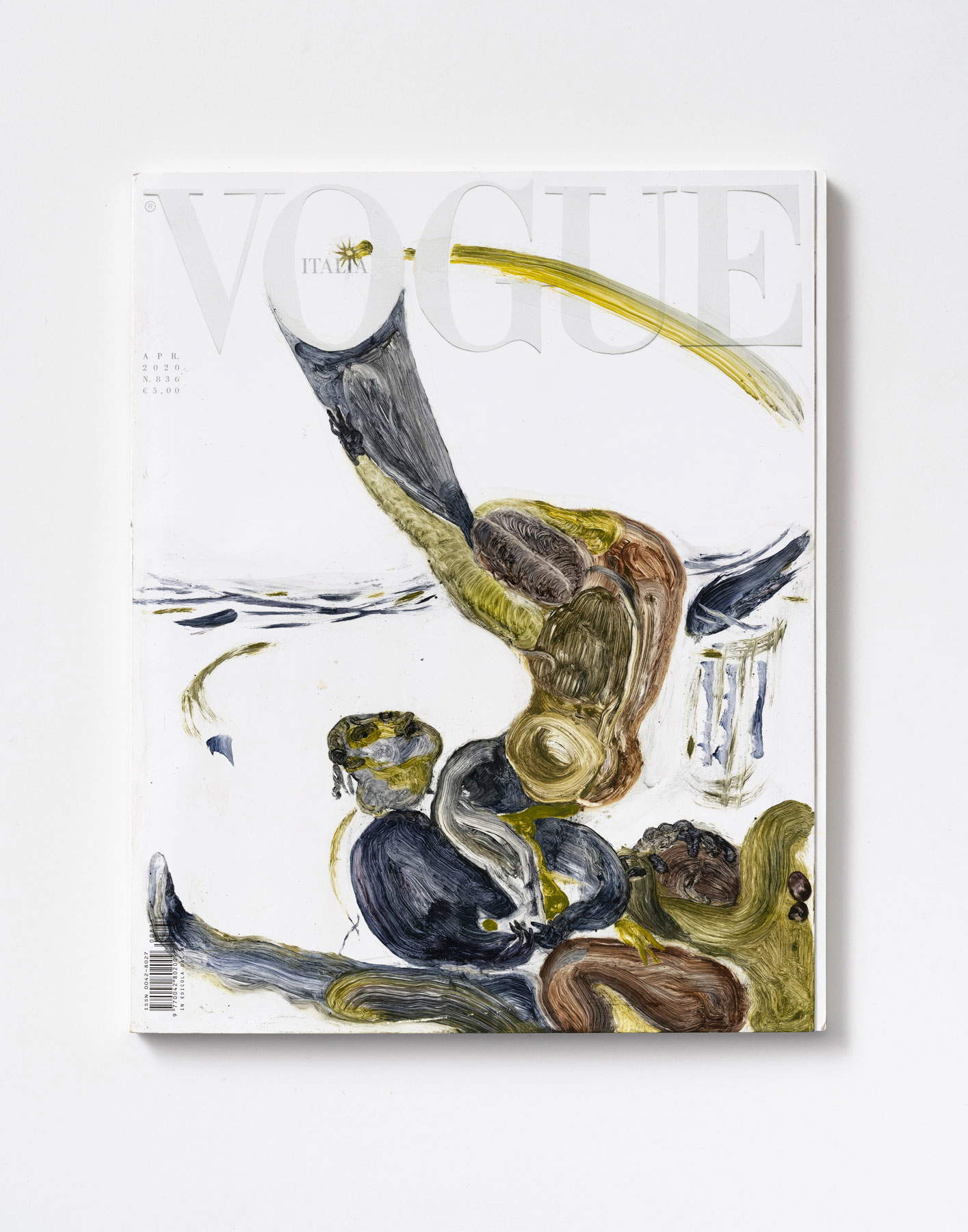

| Guglielmo Castelli, Tomorrow (2020; oil on cover). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

|

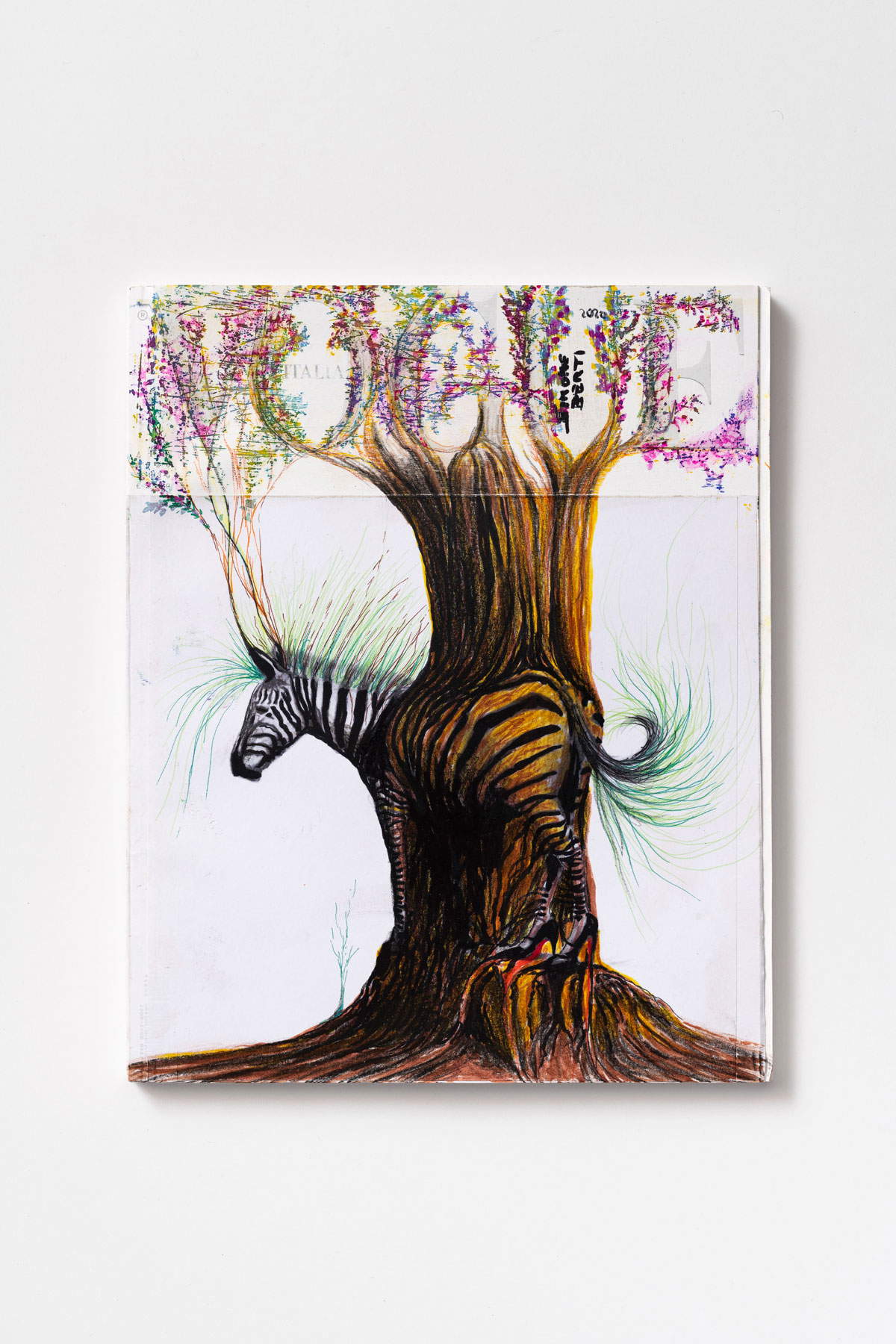

| Simone Berti, Zebra with Louboutin (2020; mixed media on paper and cover). Courtesy lartist. Photo by Giorgio Benni |

A female portrait, Arianna, stands out on Silvia Celeste Calcagno’s cover, while a broken plate(Un solco, una strada) refers to the dimension of everydayness from confinement by Silvia Camporesi but also alludes to the fractures that the pandemic has caused on our lives. Giulia Andreani, on the other hand, imagines a Monde d’après in which a girl demolishes patriarchy, and Romina Bassu, with an acrylic painting, refers back to a dimension of anxiety and inconsuetude (the cigarette held by two female feet). The Flowering Portrait of Sissi closes this all-female interlude with a delicate “gaze that blooms on the new,” to use the curator’s words. On the other hand, Pietro Ruffo and the youngest artist in the exhibition, 30-year-old Bea Bonafini, reason on the big street demonstrations: Ruffo limits himself to a portrait with banal parade slogans(There is no planet B), Bonafini creates a carving collage imagining a didactic kiss between black and white on the wave of Black Lives Matter. Alessandro Piangiamore abandons his usual languages to slap a recipe for mother yeast on the cover of Vogue, while Guglielmo Castelli, one of the most interesting young painters in Italy at the moment, populates his cover with dreamy and vulnerable creatures, a bit like all of us these days. More painting with Vincenzo Simone’s reassuring Vase of Flowers, while Marco Basta entrusts to the marker his discouragement for the period we are living: I don’t want to feel this way anymore. In A-Bee-C, Alice Schivardi sums up her confinement with a mouth and a bee, and the same mechanism governs Ludovica Gioscia ’s Affectionate Jacket, which sprinkles the cover of Vogue with fabric, leaves, wool, grass and even cat hair to create a removable envelope. The exhibition closes with Simone Berti ’s whimsical Zebra with Louboutin (an atmosphere where nature “seems to constrict and immobilize the zebra, an expression of the stasis that this period imposes on us,” Ciarallo writes), the work of Davide Monaldi, who deemed the White Issue so significant that he did not have to fill it (and therefore reproduced it in glazed ceramic), Manfredi Beninati’s reinterpretation of Michelangelo’s creation of Adam, Corinna Gosmaro ’s existentialist porcupine(We Don’t Know Yet), and Maria Crispal ’s evocative self-portrait of herself dressed in white, standing on the magazine’s vignette that reminds her of the globe, to convey, the curator explains, “a concept of global rebirth and union in the power of life.”

Of course, there are no lightning flashes because the artists in the exhibition have almost all worked according to their usual forms, but the aim of the exhibition was not to open roads never taken: it is a project of reflection on the recent past, a “choral narrative animated by variety and diversity of languages,” as Ciarallo defines it, aimed at establishing a lively dialogue with the public, and which fits well into the context of a museum that is renewing itself and aspires to become a point of reference for its community. Discovering the value of art for the community, for the territory, for the people: this is the invitation that Carta Bianca seems to be addressing, with a shortlist of artists that covers all the possible feelings generated by the pandemic, with works that address the theme sometimes with irony, sometimes with melancholy, sometimes with strength, sometimes rummaging through reality, sometimes immersing themselves in dreams. After last fall’s Ti Bergamo exhibition, Carta Bianca is probably the most interesting choral response of contemporary Italian artists to the pandemic. And it is also a demonstration that Italian art, whatever one may say about it, is there and is vital.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.