It seems to be an established practice, that guilty and senseless delay with which we in Italy reacquaint ourselves with the protagonists of artistic events between the 19th and 20th centuries. Whether out of cultural snobbery, spasmodic foreignophilia, oscillations in taste or a cult for a more remote past, the ranks of the illustrious victims of this cultural attitude are still very large. In this last handful of years we are witnessing the recovery, even by the general public, through a continuous proliferation of exhibitions, of the figure of Giovanni Fattori and the other Macchiaioli painters, who seem to have finally managed to put Roberto Longhi’s infamous anathema behind them. But a redeemed cadre is still counterbalanced by a multitude of personalities who have been lost in the folds of art history: painters, sculptors and creative people of all kinds whose artistic and life experiences are of great interest. These include, inexplicably, an artist of Lorenzo Viani’s worth.

A painter, xylographer, and writer, Viani pursued numerous artistic endeavors with high achievements in his life that began in Viareggio in 1882 and ended at the age of just fifty-four in 1936. Certainly, the redemption of the Tuscan painter has already been hoped for by considerable critics, and accompanied by a good number of publications and a few interesting exhibitions, but his work is still little known and appreciated today, so much so that even several museums that possess his paintings do not feel compelled to exhibit them. The hostility toward Viani, according to Mario De Micheli, was due to a certain “aesthetic distrust” since he never fit into the reassuring canons of formal painting of easy approval. This heretic inconvenient to both the art world and the world of letters, as Fortunato Bellonzi called him, is certainly one of the most significant profiles of Italian painting at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, but he is also among the most remarkable outcomes of certain European expressionist and social production. Here, then, the art lover cannot miss the opportunity of an encounter with Viani’s work, guaranteed by the new temporary installation of the GAMC in Viareggio, the museum dedicated to the artist, which until May 5 will host the exhibition Viani. Emotions of Humanity.

This is an exhibition initiative designed to cope with the restoration of the museum venue, the Palazzo delle Muse, by making accessible a selection of the masterpieces of the master from Viareggio present in the civic collections and enriched by sixteen paintings from private collections. To understand Viani’s art, it is also necessary to probe its biographical events, since the painter of the last and the derelict began his life’s adventure in a Versilia that was not that of the glossy seaside seasons, nor that of the seaside villas of the Lucca nobility, although his father was in the service of Prince Don Carlos of Bourbon. Instead, from an early age, Lorenzo’s imagination is dominated by forebodings of death and loneliness; he leaves the Bourbon palace to hang out with the people of the Darsena, anarchists and jail leftovers, whom Viani elects as faithful companions throughout his life. This adherence intensified when his father lost his job, and the family plunged into an abyss of misery. The young man took a trade at a barbershop, which imposed itself as a school of humanity; in fact, as he later wrote, “Before I drew these frowning faces, stitched up with gavine...I mantrugiati.” But in addition to that pitiless human sampler, he also made the acquaintance of famous people in the workshop, such as the anarchist Pietro Gori and Plinio Nomellini. The Leghorn painter in particular would play a major role in pushing Viani to take up pencil and brushes. His training, made up of wanderings through the surrounding towns and reading, also passed through the Lucca Art Institute. But by the time he arrives there, he has accumulated so many important live experiences that his consciousness has already taken a direction, and from the academy he learns only the craft: "The Greek and Roman beauties I didn’t even notice. They seemed like dead things to me. Outside I was too much in touch with life for me to enjoy the dead Gladiator, when the brawl had already shown me dying people, or the Venus de Milo, when in the hangouts of the Via della Dogana I had seen beautiful bodies in the red light of the curtains."

In the early 20th century he moved to theAccademia di Belle Arti in Florence, where Nomellini introduced him to Giovanni Fattori. The Macchiaiolo master seeing his deformed figures twisted his mouth and exclaimed, “There are mistakes, however, they are good mistakes.” And again, “they are original things, do as you see and as you feel.” And Fattori’s lesson will forever have a fundamental weight on the Viareggio artist, who found that bath of realism congenial. Conceiving painting by wide backgrounds, extreme synthesis, the use of the pictorial medium in a disenchanted manner, are only parts of the technical baggage he learned from his “daddy” from Leghorn, to which he added that thick, restless outline line reminiscent of certain Macchiaiolo etchings.

And the Fattori is also to be found in one of Viani’s later works, the first that greets visitors to the exhibition, Marble Workers in Versilia of 1934, made along with another canvas to decorate the Viareggio train station. These canvases immediately precede Viani’s last work, the frescoes in the Collegio “IV Novembre” at Castel Fusano in Lido di Ostia. Although the monumental painting does not dwell on the more tragic aspects of a derelict humanity, incidentally not congruous with an official commission, it shows a bloodless pictorial matter and a narrative by compositional groups experimented many times in large-format works, capable of profiting from different contributions, from the angular landscape of the Apuan Alps of cubist scent to his meditation on Italian primitives, reflected in the hieratic group of the Madonna and Child.

The next two rooms house works from private collections and from the Lucarelli and Varraud Santini donation, the two corpuses that have made the Viareggio museum an indispensable stop on an artistic pilgrimage in Viani’s footsteps: these canvases stand as a mournful gathering of unsavory figures, oppressed and crushed by the life that Viani encountered in brothels, shady taverns, and more generally in all those slums washed by the humors of the world, of which the painter was not only a spectator or cantor, but to which his evangelical adherence went.

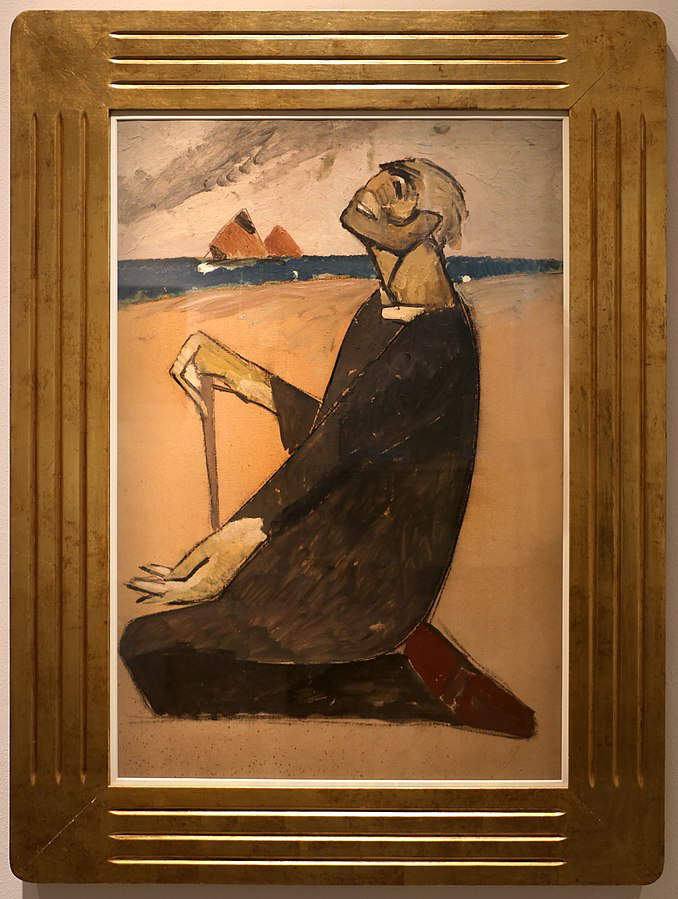

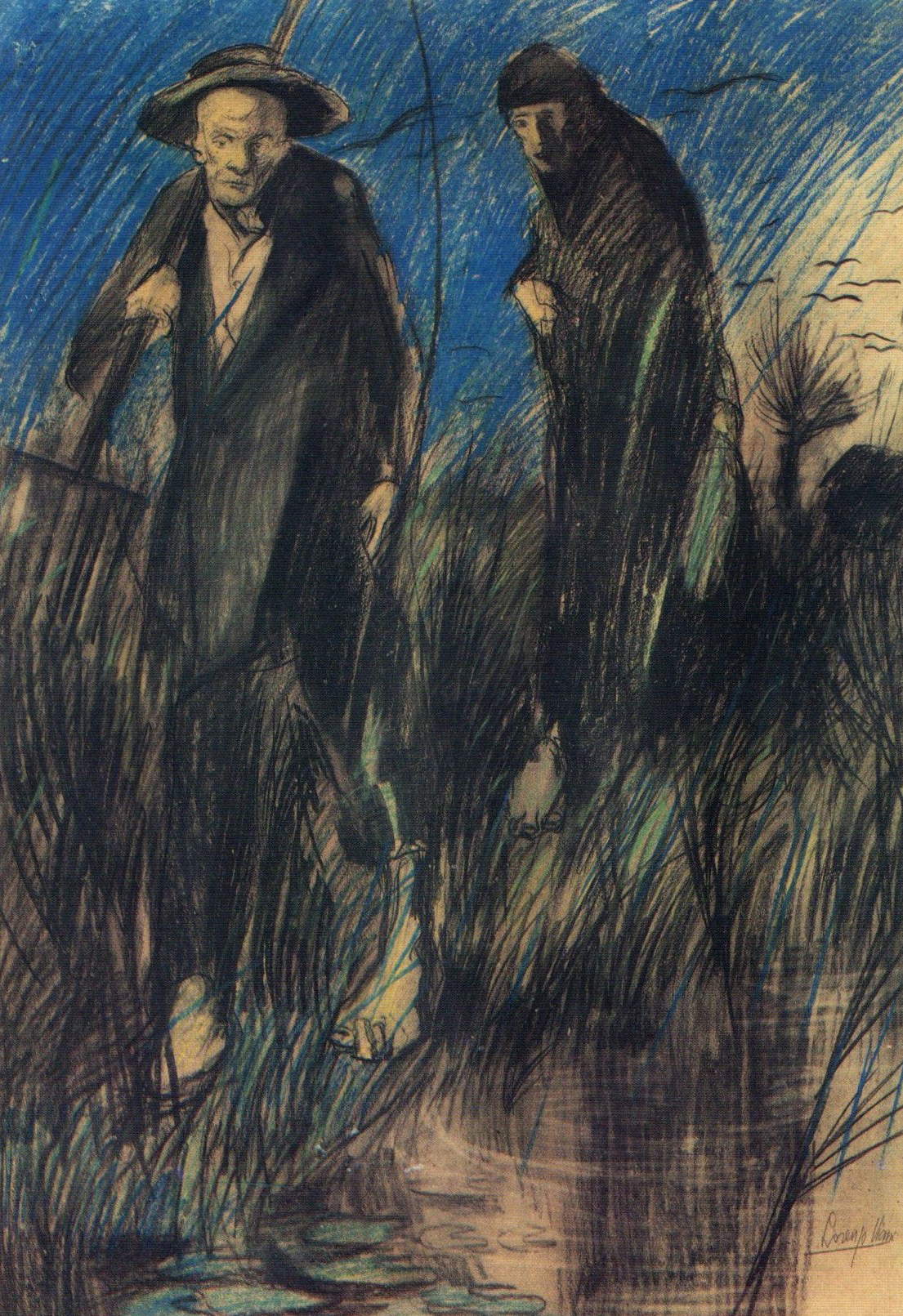

No attempt should be made to periodize Viani’s works, since they are marked by often different styles and pictorial temperatures: after all, as De Micheli pointed out, the Viareggio artist “did not aim at formal coherence, but at effectiveness.” Sometimes one sees in them again an italic and caricatured Daumier-like taste as in the Beggars, or in the Wayfarer, at other times he seems poised between the hallucinated visions of Ensor deprived by carnivalesque colors and the flat background of Toulouse-Lautrec, as in the heads of the Parisian women. The latter also bear witness to his sojourns in Paris, where he goes to “aberintare” (to use a word found in his account devoted to the Ville Lumière, which, as one can imagine, is not that of the boulevards or elegant cafés frequented by the Impressionists).

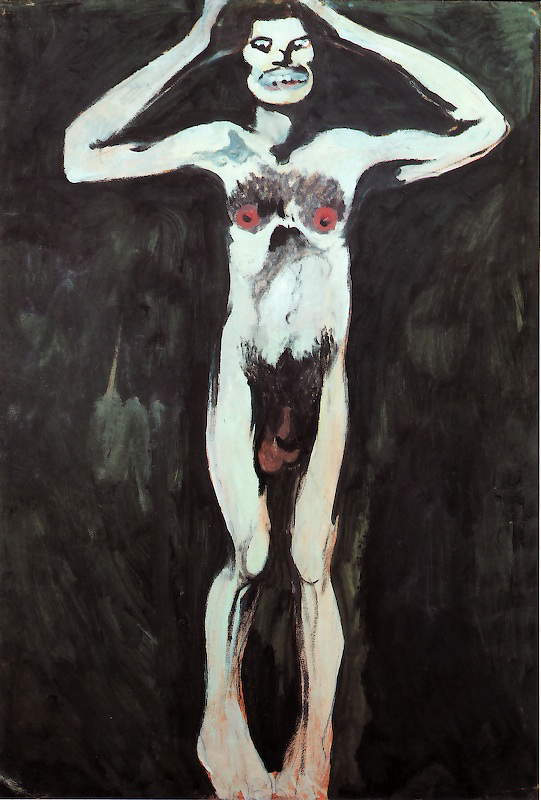

From his canvases protrude limp and soft bodies as in the Whale, wax masks, livid flesh or straw puppets like those in the Family of the Poor, empty eyes devoid of light in his Blind Men. Even more disturbing is the figure in The Obsessed One, a work whose unprecedented crudity suffered numerous censures over time. Contrasting in this sea of dense despair is the painting Borsalino (portrait of Gea della Garisenda and Teresio Borsalino), circa 1929, which depicts the soprano singer with the senator son of the entrepreneur of the famous hat house. The painting shows a worldly setting and a “fatal and D’Annunzio-like beauty,” as Enrico Dei writes of it, probably because it was a work born on commission. Also interesting is the youthful piece Strada viareggina, where a city scene is depicted with extreme conciseness and slick calligraphy, in tones so didactic as to recall the same language as the ex voto tablets found in countless shrines. Equally remarkable, though of a completely different temperament, is the painting Monte Costa. Here, cubist geometries rather than showing formal deconstruction complicate the plot, while the lean chromatic matter lets the cardboard support surface, giving rise to a complex abstract play of polychrome tessellations.

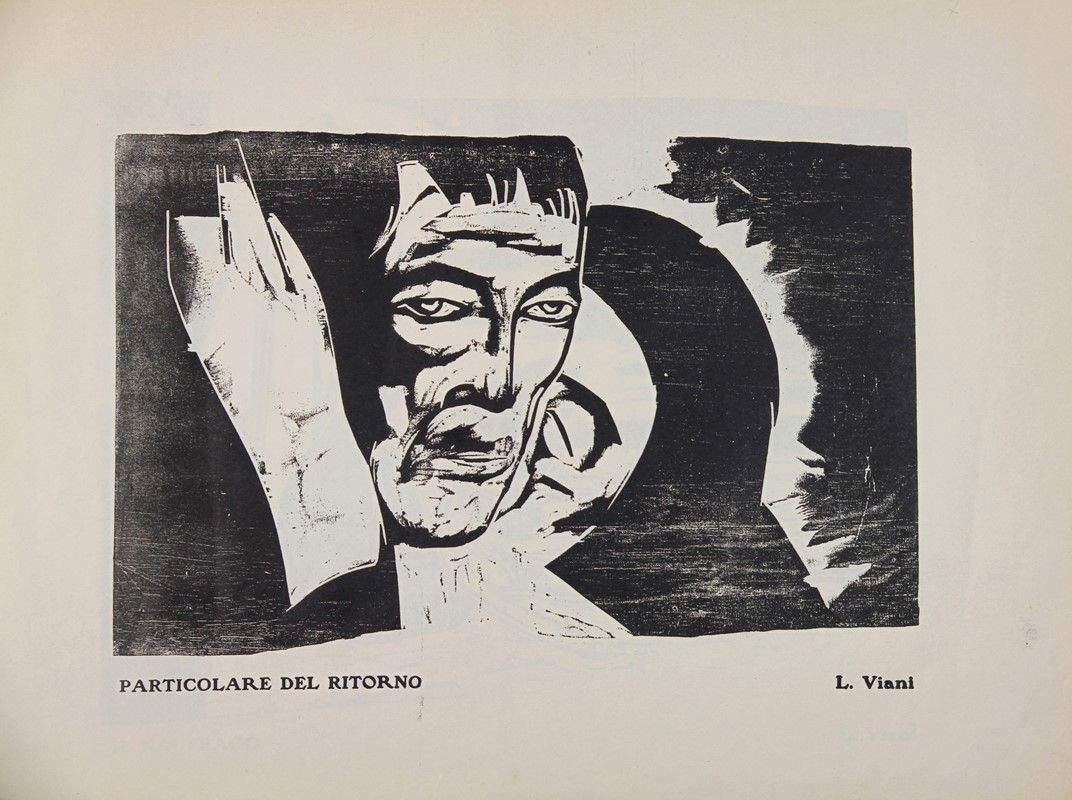

We then come across Viani’s production of woodcuts, a selection of which is presented: the artist sculpted more than 250 woodcuts during his lifetime, in the search for a pure line and fascinated by the dramatic effects that black and white bichromy offered. In this field, too, he is among the most significant artists of modernity. “Gabriele D’annunzio told her of mystical strength. Grazia Deledda: mystical delinquency. Leonardo Bistolfi: terrible imprints. Ceccardo Roccataglia Ceccardi: earthly hell. Umberto Boccioni: unwavering faith.” These poignantly powerful works sometimes originate as studies for his paintings, but they acquire such expressiveness that they become independent masterpieces.

Viani’s greatness finds further confirmation in the exhibition in two of his most celebrated masterpieces, the monumental canvases of the Blessing of the Dead at Sea and the Holy Face. These are works where the painter’s making becomes great, in concatenated narratives of dense symbolic value. The Blessing unfolds as an ancient frieze of just under 4 meters, in which five scenes conceived as if they were sculptural groups alternate.

The

The

Depicted here is the procession held every year in Viareggio to commemorate the dead who disappeared in that “endless cemetery” that is the sea, as Viani called it, and most of the time could not even aspire to a burial. Seafarers whose fate was not even known with certainty, but whose long absence accompanied by common sense suggested lost forever, leaving only a memory ashore, and a widow and a few orphans, who in memory could barely find consolation, but which would be of little use in the constant struggle with daily survival. These martyrs were seen by Viani as “mighty statues of pitch, matted in monk’s cloths, prolific, with the hen of children attached to their skirts and the little one in their necks. In every boat that passes on the horizon they see the one on which their man travels.” From the left we can see a group of widows, bracing themselves against each other, one of them clutching a swaddled baby, and the bulging belly betrays her being pregnant again, for life does not stop even in tragedy. For that matter, the same bairn flaunted as a baby Jesus during adoration instead faces the mournful, hollowed-out face of the woman, as if in a confrontation between death and life.

Thereturn is the next group marked by an embrace that makes the two figures a single monolith; a woman encircles with her arms her man whom she thought she had lost at sea, but even in this reunion there is no serenity, but rather commotion and despair over a fate that this time has been merciful but is unlikely to be so again. The center of the composition is punctuated by the Holy Face, from where the light that reverberates throughout the canvas radiates; this is the famous icon of the crucified Christ that is preserved in the Cathedral of Lucca, at his feet prostrates an audience of cloaks black as night. This is followed by a kind of sinister Visitation, in which two women, like gloomy vestals, give their mute support to a companion, whose husband has followed the same fate as theirs. In the far right is pressed a family with offspring, also distressed, prodromes of the doom to which even these new souls will not be able to deny themselves.

The epic outlined by Viani moves between sacred and secular, summing up between a language of ancient memory and a very modern composition, between a personal and a universal narrative conveys the archetypal message of grief. The canvas with the Holy Face also moves on the same assumptions: a sampler of mourners toil on the Darsena, annihilated by the drowning of a child, waiting for a theophany that has not manifested itself, taking away with it all hope.

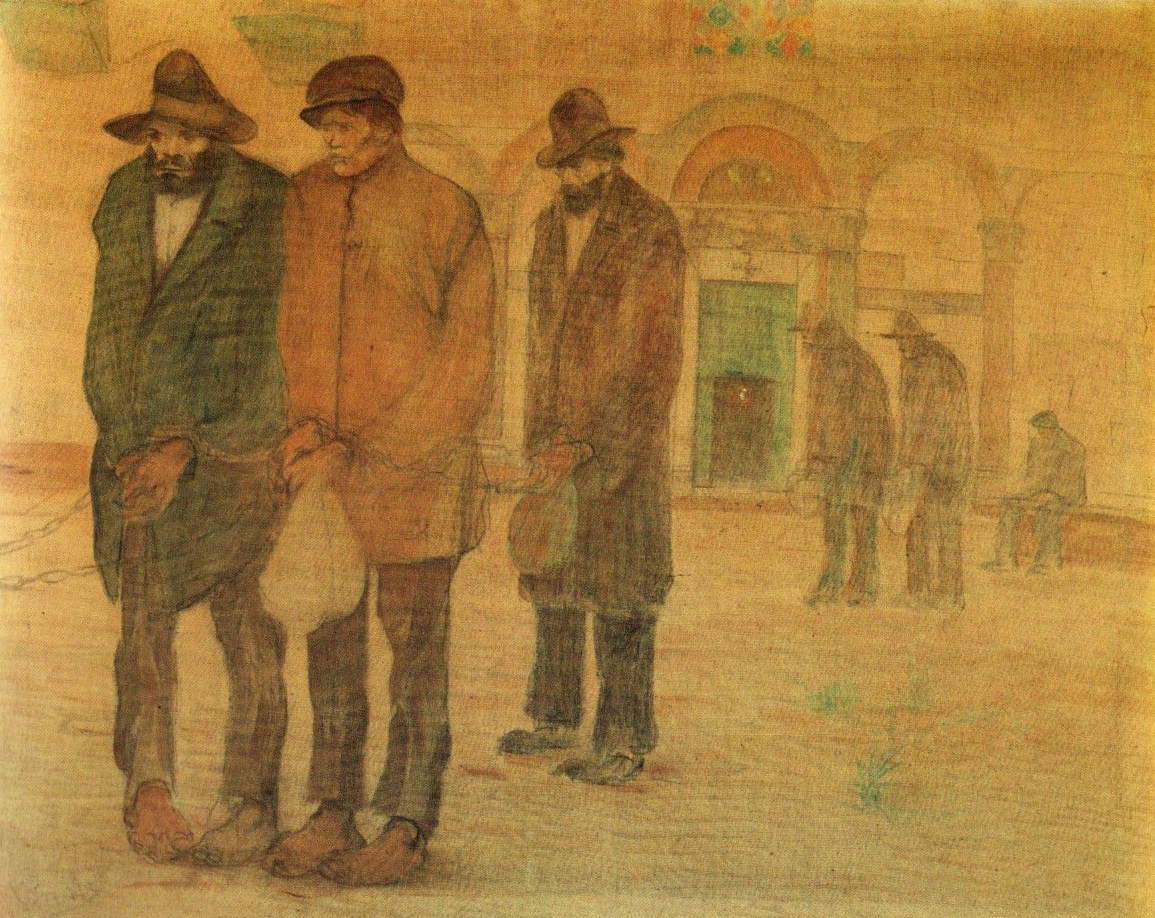

There are still many works that deserve mention, for every representation that comes out of Viani’s brush is a universe that imposes itself with force and immediacy. Among them are the Carcerati where the poverty of the pictorial medium, played on the bled-out matter, and the dull palette built on brown and ochre tones seem to adhere to the theme with a strong social imprint; or S. Andrew, a canvas that shows in front of a church the eternal dualism between the opulent bourgeoisie and the starving petty people; or the small clay sculpture of the Madwoman’s Head, modeled after the example of Medardo Rosso, but recalling the interest in psychic imbalances already probed by Messerschmidt.

Thus the new exhibition at the GAMC in Viareggio, while remaining far from the media hype, really stands as an indispensable stage in the recovery of the art of Lorenzo Viani, the painter who met Picasso and was disappointed by him because he was denoted by the “superior indifference of the creator.” And after all, how could he have shared this detached attitude he who never wanted to abandon that humanity which, though grotesque, fallacious, miserable and disgusting, he always recognized as his sister?

The author of this article: Jacopo Suggi

Nato a Livorno nel 1989, dopo gli studi in storia dell'arte prima a Pisa e poi a Bologna ho avuto svariate esperienze in musei e mostre, dall'arte contemporanea alle grandi tele di Fattori, passando per le stampe giapponesi e toccando fossili e minerali, cercando sempre la maniera migliore di comunicare il nostro straordinario patrimonio. Cresciuto giornalisticamente dentro Finestre sull'Arte, nel 2025 ha vinto il Premio Margutta54 come miglior giornalista d'arte under 40 in Italia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.