by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 08/03/2017

Categories: Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Artemisia Gentileschi and Her Time' in Rome, Museo di Roma (Palazzo Braschi), through May 7, 2017.

In order to approach the exhibition Artemisia Gentileschi and her time, underway at the Museum of Rome until May 7, in the most correct way, the first necessary condition is to get rid of any preconceptions: before crossing the threshold of Palazzo Braschi, one might in fact think that it is the usual, umpteenth exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi (Rome, 1593 - Naples 1653). The Roman exhibition in fact follows the many reviews that, in recent years, have been dedicated to the seventeenth-century painter, and in whose favor the authentic myth originated from the woman’s tormented biographical story and adequately fed by novels and films has played. More in detail, the Palazzo Braschi exhibition arrives (excluding the small Pisan review in 2013) just five years after the major event at Palazzo Reale in Milan, which in turn came ten years after the first monographic exhibition dedicated to Artemisia (and her father Orazio), which was held in three stages (Rome, New York and Saint Louis) between 2001 and 2002. The substantial difference that separates Artemisia Gentileschi and her time from all the operations that preceded it consists in the fact that, of the approximately one hundred works on display at Palazzo Braschi, those by Artemisia constitute the clear minority (in fact, there are twenty-nine): the curators have chosen to give more space to the historical-artistic context within which the painter’s career unfolded.

The result is a long exhibition, which follows Artemisia in her movements (the sections are in fact dedicated to the different moments of her career), and not particularly easy: not only because the Rome of the first decade of the seventeenth century, the Florence of the 1920s and the Naples of the 1930s-1940s presented different realities (so much so that a triple curatorship was necessary to organize the exhibition in the best possible way: Judith Mann for the Roman section, Francesca Baldassari for the Florentine one, and Nicola Spinosa for the Neapolitan one), but also because one of the problems of the exhibition consists in the fact that sometimes the visitor is not put in a position to fully grasp Artemisia’s debts and stylistic legacies. For this reason, the affinities or divergences that unite or separate her from the many artists chosen to contextualize her works emerge mainly on the iconographic level. In the section on the return to Rome, for example, one will notice how Domenico Fiasella, in his Judith of Novara, signed and dated 1626, introduces the absolute novelty of the heroine passing the sword with which she has just decapitated Holofernes over the flame of a candle, as a sign of purification (despite the fact that it is somewhat difficult to understand for what reasons the Ligurian painter was slipped into the aforementioned portion of the exhibition, given that he was in Genoa in the 1920s).

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (c. 1616-1617; oil on canvas, 146.5 x 108 cm; Florence, Uffizi) |

|

| Domenico Fiasella, Judith with the Head of Holofernes (1626; oil on canvas, 117 x 135 cm; Novara, Musei Civici) |

Aside from the shortcomings mentioned above, which we nevertheless feel to be understandable for an exhibition of such proportions, capable of rereading Artemisia’s career with an unprecedented slant, it is also necessary to record some significant novelties proposed by the curators. One of the most important is a drawing conserved in a private collection in London and identified as a self-portrait of Artemisia: it would be, the curators assure, theonly drawing we know that can be referred to the artist, also important as proof of the Tuscan ascendancy of her training. Other novelties concern the reading of the figure of Artemisia herself, beginning with the attempt to remove the prejudice of the “painter in constant struggle against the world” that would have conditioned her entire career (indeed already long since completely alien to scholars, but still resistant among the general public): strolling through the rooms of the exhibition we will realize not only that Artemisia had managed to overcome with great speed the vicissitudes related to the violence she suffered at the hands of Agostino Tassi (indeed: we will discover a perhaps little-known Artemisia, that is, a woman well inserted in the courts of the time, also capable of entertaining extramarital relationships, poorly tolerated by her husband), but also how the violence inherent in many of the painter’s works is actually recurrent in the production of many other artists of the time. Another major novelty is the same intent to reconstruct Artemisia’s career by making evident her connections with the world around her: an intent that had often failed in previous exhibitions, and which is perhaps the main reason for visiting the exhibition, not least because the loans (not only those of Artemisia) are for the most part of sublime quality.

Certainly, the debut of the exhibition proves to be particularly laborious, because reconstructing the early stages of Artemisia’s career is still not an easy operation, due to the fact that the fixed points on which we can base ourselves are very few. This does not detract from the fact that the first two rooms, dedicated to Rome in the early seventeenth century, although with Artemisia absent, offer us a very important sample of the context in which the young woman took her first artistic steps: Giovanni Baglione, Paolo Guidotti and Bartolomeo Manfredi are entrusted with the task of providing three representations of the biblical Judith that will recur in Gentileschi’s production (the heroine’s presence is in fact almost constant throughout the exhibition). José de Ribera’s Magdalene is effective (although it dates back to 1618: we are therefore at a time when Artemisia had already left the eternal city), but more consistent is the presence of two works by a too often neglected painter like Antiveduto Gramatica, who participates with a Saint Cecilia and a Cleopatra placed on the same wall, side by side: works that show us how the painter of Sienese origin was among the first to be fascinated by Caravaggio’s lesson. The great regret is that we do not have any work by Caravaggio on display: however, since we are in Rome (and, moreover, just a few meters from San Luigi dei Francesi), the visitor will be able to easily make up for this shortcoming.

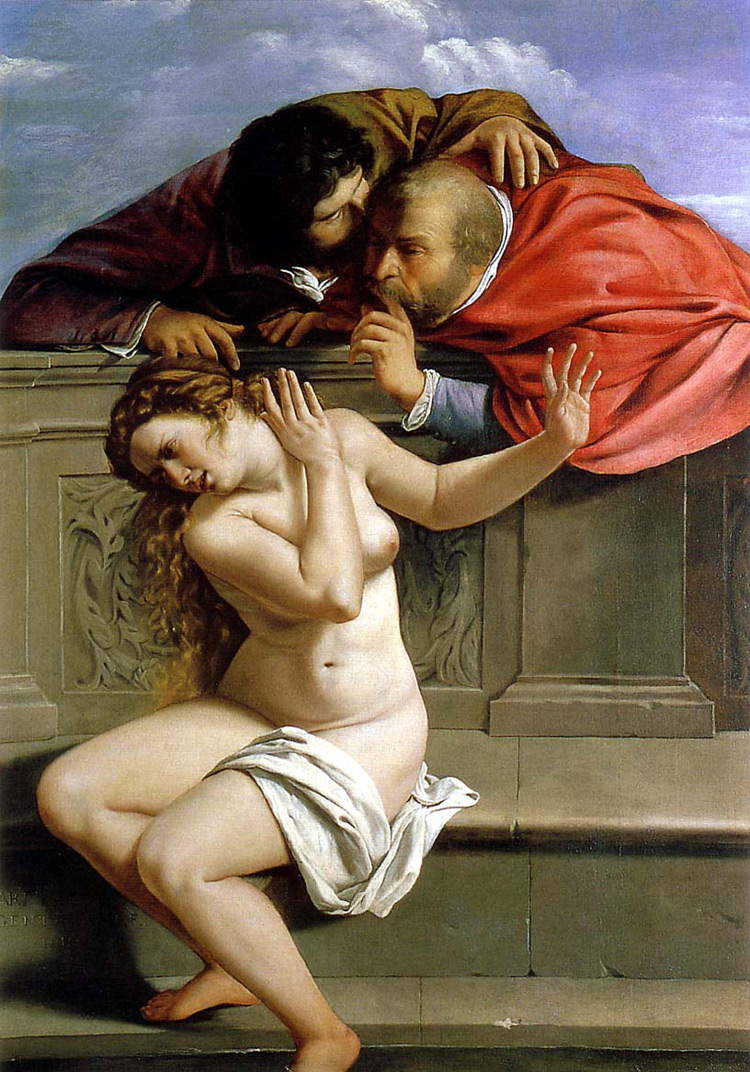

Mention was made, just above, of the staples of Artemisia’s early activity: one of these is the Susanna and the Old Men of Pommersfelden, one of the excellent loans in the exhibition as well as the first work by the painter that we encounter along the way. In particular, we find the painting in a room that seems almost set up to pay due homage to the myth of the "violated painter." Proof of this is the fact that the Susanna is in direct vis-à-vis confrontation with a painting, Time Discovering Truth and Unmasking Deception, which scholar Anna Orlando wanted to attribute to Domenico Fiasella (and on this attribution one would have to put all the conditionalities of the case). In the exhibition it is placed next to Artemisia’s Danae, which Fiasella would have slavishly taken (this would be a unique case in his Roman production) for the figure of Truth: in the work attributed to Fiasella we wanted to imagine a certificate of solidarity that the painter from Sarzana would have paid to the offended young friend. On this painting we must therefore refer the reader to a subsequent article, which we will publish in the coming days. And, still speaking of discussed works, in the same environment the visitor will have the opportunity to question himself in front of the Judith from the collection of Fabrizio Lemme: a painting that, due to the evident discordances with the other known works referable to the three-year period 1610-1612, is considered of uncertain attribution and still the subject of lively debates (the last of which fomented by Vittorio Sgarbi, who considers it to be by the hand of Caravaggio).

|

| Roman section: the works of Antiveduto Gramatica (left the Saint Cecilia, right the Cleopatra) and Giovan Francesco Guerrieri’s Penitent Magdalene |

|

| Artemisia: the Susanna of Pommersfelden and the Judith of the Pitti Palace |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Old Men (1610; oil on canvas, 170 x 119 cm; Pommersfelden, Kunstsammlungen Graf von Schönborn) |

|

| Comparison between the Truth attributed to Domenico Fiasella and Artemisia’s Danae of Saint Louis. |

The Florentine section is probably the one that works best, for at least a couple of reasons. First, because it is divided into two distinct segments that delve, in the first case, into the Florentine environment and Artemisia’s debts to it, and in the second, conversely, into what the painter left to the artists of early 17th-century Florence. And then because, net of some absences (there are, for example, no works by Matteo Rosselli), it well documents the artistic scene in the capital of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, whose relations with Rome were closer than one might imagine: in fact, Grand Duke Cosimo II had works by the main artists active in the Papal States, from Gerrit van Honthorst to Bartolomeo Manfredi and Bartolomeo Cavarozzi, via Battistello Caracciolo, who worked in person at the Medici court, arrive in Florence. To attest to such frequentations we therefore have a Noli me tangere by Battistello, but we also have works that bear witness to the reverse path, that of Tuscan artists who studied in Rome and returned to Florence: significant therefore is the presence of artists such as Filippo Tarchiani and Andrea Commodi. Artemisia, for her part, in addition to receiving an excellent welcome in the city (her relations with the Medici and her entry, dated 1616, into theAccademia delle Arti del Disegno, the only female presence, prove this), was able to make the most of her Florentine sojourn to “smooth out” the sharper and less gentle points of her painting by deriving from his closeness to the most refined Tuscan painters of the time (in the exhibition, the comparison with Cristofano Allori and his Judith is inescapable, but also the one with Jacopo Chimenti, whose Saint Julian is present), a preciousness and softness capable of making his art undoubtedly finer.

In the room devoted to Artemisia’s influence on the Florentine milieu, the absolute protagonist is theAurora from around 1625: according to the curators, the echoes of the painter’s figure setting reverberate in the compositions of some artists of the time. Unmissable, for example, is the comparison with the despair of Venus Mourning the Death of Adonis by Francesco Furini, the most sensual painter of seventeenth-century Florence, which is in turn set against (on the same wall) the gentileschian truculence of Budapest’s Jael and Sisara (another first-rate loan) that, in a further game of bloody cross-references, is placed next to the Medea and recalls works from the previous room, such as the two Judiths, in the Uffizi and Capodimonte versions (the latter, however, arrived at the exhibition a few months late). The presence of subjects tackled by other painters with no less violence than Artemisia’s (perhaps only Felice Ficherelli’s Lucrezia, who paints rape, yes, with a vivid sense of tragedy, but also with extreme elegance and even a certain erotic charge, escapes from this logic) is perhaps the most tangible demonstration of the assumption mentioned at the beginning, namely that the crudity of certain paintings by Artemisia is not to be put so much in relation to her personal events as to the taste of the time.

|

| Florentine section: on the left is Cristofano Allori’s Judith, on the right is Andrea Commodi’s |

|

| Florentine section: on the left is Artemisia’s Judith (Uffizi) on the right is Filippo Tarchiani’s Pietà |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Aurora (ca. 1625; oil on canvas, 218 x 146 cm; Collection Alessandra Masu) |

|

| Francesco Furini, Venus Mourns the Death of Adonis, detail (c. 1625-1626; oil on canvas, 233 x 190 cm; Budapest, Szépmuvészeti Múzeum) |

|

| Artemisia: left Giale and Sisara (Budapest), right Medea (private collection) |

|

| Felice Ficherelli, Tarquin and Lucretia (c. 1640; oil on canvas, 117 x 163.5 cm; Rome, Accademia di San Luca) |

Having passed the room and narrow corridors devoted to Artemisia’s return to Rome (to be placed between 1620 and 1627), rooms in which the curators have proposed a quick but compelling comparison with Simon Vouet and where violent subjects (such as Giuseppe Vermiglio’s Giale and Sisara ) return, the exhibition throws itself headlong into the Neapolitan period, which opens with an absolute masterpiece such as the New York Metropolitan ’s Esther and Ahasuerus, a painting in which the painter still reaps the fruits of her Florentine sojourn for a work devoted to the most sophisticated elegance (it would have been made at the dawn of her Neapolitan sojourn, and certainly begun even before the move: it is, however, a work that is not easy to date). Those who like to get excited in front of paintings, or those who are used to being carried away by the immediacy of sensations, will find the juxtaposition of the work from the Metropolitan with two other striking works such as theAnnunciation from the National Museum of Capodimonte and José de Ribera’s tragic Lamentation over the Dead Christ, on loan from the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, to be impressive. After saving the obligatory selfie on your cell phone in the small room set up for the purpose (the organizers invite you to share your self-shots on social networks, complete with hashtag, #ArtemisiaRoma: after all, it’s fun and it’s also the only opportunity to use your own camera, since you are not allowed to bring memories of the exhibition with you, photos having been banned), you will reach the room that, in greater depth, gives us an account of what was happening in Naples in the 1730s. Ample space is devoted to the figure of Massimo Stanzione, not only as one of the most important artists on the Neapolitan scene, but also because he was in close contact with Artemisia and collaborated with her, for example between 1635 and 1637 in the Pozzuoli Cathedral. Interesting is a Lot and Daughters on loan from the National Gallery in Cosenza, which is particularly illustrative of Stanzione’s style, midway between naturalism of Roman ancestry (his relations with Vouet are highlighted) and Bolognese classicism (let us not forget that Domenichino was present in Naples in those years).

If it is necessary to agree with Nicola Spinosa, who in the catalog essay on Artemisia’s Neapolitan sojourn states that “the results found in the few surviving works from her early Neapolitan years do not appear brilliant,” it is also necessary to highlight the quality of a work such as the Penitent Magdalene from a private collection, placeable in the early 1940s (thus following the brief London interlude), which dialogues with the verism of Ribera or Bernardo Cavallino. A verism of which the exhibition punctually gives an account, also dwelling on lesser-known figures but no less worthy of interest: one name above all is that of Francesco Guarino, present with a good selection of works, including a very particular Santa Lucia capable of attracting attention both for the popular beauty of the protagonist and for the grim detail of the still bleeding eyes resting on the book. Instead, it is the prerogative of a comparison between the Trionfo di Galatea, created by Artemisia in collaboration with one of her pupils, Onofrio Palumbo, and Bernardo Cavallino ’s Trionfo di Anfitrite (in the exhibition the latter work undergoes a change of subject, since it was also believed to be a Trionfo di Galatea), to face the definitive move to Naples, where Artemisia would remain until her death in 1653. We are in the extreme stages of the painter’s career, but the intention to “dialogue” with colleagues is not diminished: in this case the interlocutor is Bernardo Cavallino, who, moreover, has also been indicated as a possible collaborator on the Trionfo di Galatea, given the obvious relationships between Artemisia’s canvas and that of the younger Neapolitan artist.

|

| Neapolitan section: on the left Ribera’s Lamentation, in the center Artemisia’s Esther and Ahasuerus, on the right Artemisia’s Annunciation |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Penitent Magdalene (c. 1640-1642; oil on canvas, 125.2 x 179.8 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Francesco Guarino, Santa Lucia (c. 1645; oil on canvas within painted octagonal outline, 85 x 71 cm; Cosenza, Banca Carime collection) |

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi and Onofrio Palumbo, Trionfo di Galatea (c. 1645-1650; oil on canvas, 190 x 270 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Bernardo Cavallino, Triumph of Amphitrite (c. 1648; oil on canvas, 148.3 x 203 cm; Washington, The National Gallery of Art) |

The exhibition at Palazzo Braschi ends by dwelling briefly on the aforementioned sojourn in London, which Artemisia made in order to join her old father who worked there, and which would most likely be placed between 1638 and 1640. This parenthesis in the exhibition is treated rather hastily, but nonetheless sufficient to establish a comparison between what is perhaps Artemisia’s main work of this period, the so-called Cleopatra, which the curators believe may be the “Saint Resting a Hand on Fruit” recorded in the inventory of Charles I of England’s possessions after his beheading, and Orazio Gentileschi’s Loth and the Daughters, a painting made during her London sojourn and now preserved in Bilbao: the preciousness and iridescence of Artemisia’s canvas (a work that, moreover, closes the exhibition) are placed in direct relation to those of her father.

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, Cleopatra (ca. 1639-1640; oil on canvas, 223 x 156 cm; Paris, Galerie G. Sarti) |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, Lot and Daughters (1628; oil on canvas, 226x282 cm; Bilbao; Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao) |

It is precisely the figure of Orazio Gentileschi, despite the unquestionable weight he had in Artemisia’s formation (but also later), that remains decidedly on the sidelines: the only four works the exhibition makes use of are insufficient for a reconstruction of the relationship between father and daughter. Of course: one could object by saying that this task has already been accomplished by some of the previous monographs. But it is also true that if an exhibition intends to place the figure of Artemisia within her art-historical context, it is difficult to accept the lack of an adequate and possibly thorough examination of the artistic connections between the two. Nevertheless, the exhibition has many merits: in particular, there was a need for an exhibition capable of avoiding chasing the myth of Artemisia and able to propose a careful reading of both her art and the circles she frequented during her long career. The curators could, yes, have dealt with some passages better, but this cannot make us desist from appreciating the hard work that went into setting up an exhibition that took years of effort and is distinguished by the richness, variety and quality of the works on display.

The honest catalog traces the painter’s entire career: to the contributions of the three curators (two by Judith Mann, in this case one on her training and one on the Roman years between 1620 and 1627, one by Nicola Spinosa on the Neapolitan period, and one by Francesca Baldassari on the years in Florence) are added a few pages that Cristina Terzaghi devotes to Artemisia’s London sojourn, a brief essay by Jesse Locker on Artemisia’s “forgotten years” in Venice (almost entirely forgotten, moreover, even by the exhibition itself: the catalog therefore fills this sort of “void” that instead connotes the exhibition itinerary), and an essay by the aforementioned Anna Orlando on the relations between the Gentileschi and Domenico Fiasella (the only artist, outside of the protagonist, to have received the honor of a dedicated essay). This is a contribution that has already caused discussion in Liguria and, like the attribution to Fiasella of the Truth placed next to Artemisia’s Danae, will need further study. In closing, some “notes” by Maria Beatrice Ruggeri about the artist’s painting technique. The catalog nicely completes an exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi that we can finally say is free of rhetoric, capable of dispelling any doubts about the appropriateness of the operation, and effective in its intent to propose a serious popularization on the artist. It will probably not mark decisive breakthroughs in the field of Artemisia studies, but it certainly does not lack all the ingredients to consider it an exhibition of depth.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.