To the various pieces that, in recent years, have contributed to the reconstruction of the lively and multiform artistic and cultural reality of seventeenth-century Genoa, and particularly that of the first three decades of the century (among the most recent it is worth mentioning the excellent monograph on Luciano Borzone last year), one of fundamental value has recently been added: the exhibition Sinibaldo Scorza. Fables and Natures at the Dawn of the Baroque, an exhibition to reread, rediscover, recollect, study in depth and give adequate and proper dignity to an artist like Sinibaldo Scorza (Voltaggio, 1589 - Genoa, 1631), a name that for a long time remained almost unknown to the general public and relegated to the margins of critical interest.

What opened at Palazzo della Meridiana (and will run until June 4) is the first exhibition ever dedicated to the Voltaggio artist and, as curator Anna Orlando states in the preface of the catalog, it is both a point of arrival and a point of departure. Point of arrival, because an exhibition of such importance required a long and punctilious research work, conducted in an irreproachable manner by a first-rate scientific committee: the curator’s merit is also that of having gathered many of the best experts on the Genoese seventeenth century so that an in-depth examination of the entire known corpus of Sinibaldo Scorza’s works could proceed. The result is therefore a review that gathers a very high percentage of the painter’s known paintings, to which is added a collateral event, the exhibition of drawings preserved in the Strada Nuova Museums, currently underway at Palazzo Rosso, which will be briefly mentioned at the end of this article. Starting point, because from documentary evidenceî we know that there is still much to discover about Sinibaldo Scorza: we have news of paintings certainly made by ours, but given up for lost or not yet identified, such as the twelve canvases depicting “various instories, battaglie and hunts and markets” that were in the collection of the man of letters Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale, or the miniatures owned by Raffaele Soprani, and again many of the drawings and paintings mentioned in the post mortem inventory of the artist’s possessions, or the works mentioned in the Savoy inventories at the time of Scorza’s stay in Turin. The hope is that the present Genoese exhibition may also be a stimulus for new research.

|

| First room of the exhibition Sinibaldo Scorza. Fables and natures at the dawn of the Baroque. |

The intelligent scanning of the exhibition proceeds by thematic sections that do not follow the chronologicalcourse of Sinibaldo Scorza’s career, and perhaps for this very reason induce a better grasp of two fundamental aspects of his art (also ascribable to all of the most up-to-date Genoese art of the early seventeenth century): his insertion into a wide-ranging context of international caliber, and the dense links between visual arts and literature. In the exhibition there is frequent insistence on a peaceful and established fact, namely, the primacy (at least in Genoa) to be attributed to Sinibaldo Scorza when it comes to painting animals: the voltaggino was, in other words, the first “animalist” of seventeenth-century Genoese art. This particular predilection for the natural subject that distinguished Sinibaldo’s artistic career in its entirety has its roots in the coeval Flemish art, which the painter was able to study lavishly on the one hand thanks to the availability of “various prints by Germans, Flemish and Bohemians” mentioned in his master’s inventory, that Giovanni Battista Paggi who was also a mentor to such an exalted painter as Domenico Fiasella, and recalled in Agnese Marengo ’s catalog essay that focuses precisely on the relations between Sinibaldo Scorza’s work and Nordic art, and on the other through direct observation of the works produced by the Flemish artists present in Genoa. It is worth remembering that Genoa at the time rose to the role of a first-rate international artistic and cultural center: suffice it to say that the cultured patrons active at the time did their utmost to bring to the city artists such as Caravaggio, Orazio Gentileschi, Pieter Paul Rubens, and Anton van Dyck, all of whom were present on the shores of the Ligurian Sea in the space of fifteen years. And alongside the heaviest names on the art scene, it is necessary to add a vast array of artists perhaps little known to most, who sojourned in Genoa between the 1910s and 1920s and to many of whom Sinibaldo Scorza owes more than one debt: already Luigi Lanzi, in his famous Storia pittorica dell’Italia, had described Sinibaldo as a painter “guided by natural talent” such as to make it difficult to find, in Italy, a “brush that so well grafts Flemish taste onto our own.” Anna Orlando enumerates and Agnese Marengo elaborates on the list of painters whose work is echoed in Scorzian production: the brothers Cornelis and Lucas De Wael, Jan Wildens, Jan Roos, Gottfried Waals (all, with the exception of Waals, featured in the exhibition).

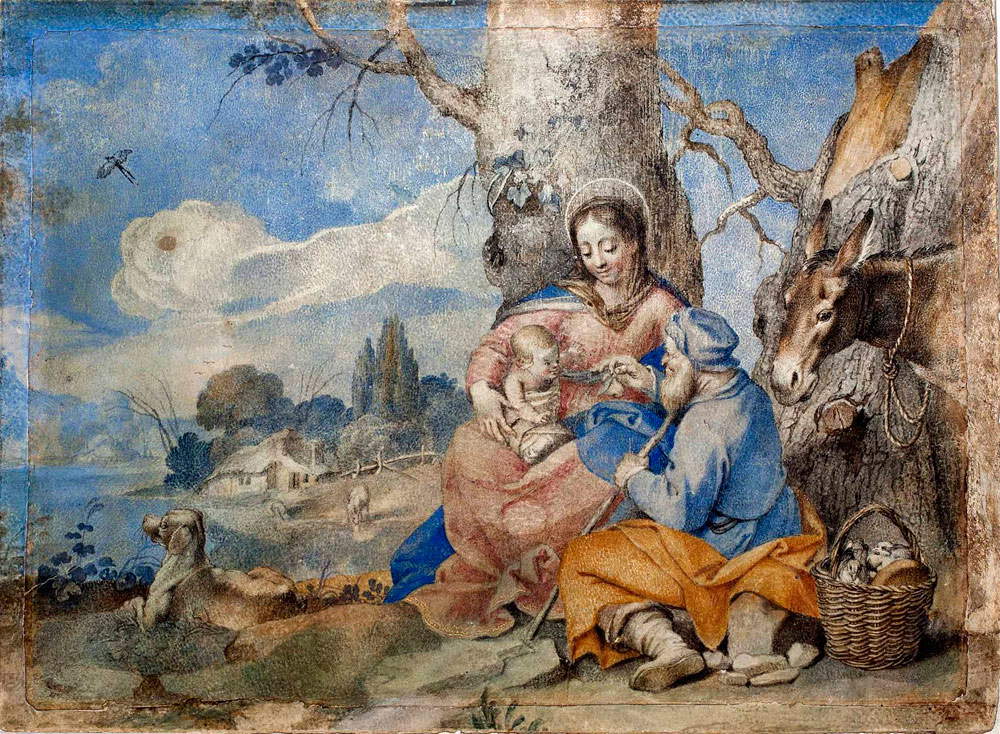

Such echoes appear evident even where the “animalistic” datum is limited to the role of comprimario: the most important example is Jesus Served by Angels, on loan from the Capuchin Art Gallery in Voltaggio, among Scorza’s few large-format works, as well as among the few for public use. It is a painting, as Agnese Marengo explains in the catalog, “where there are evident ultramontane accents, in the construction of the scene, in the posturing of the figures, in the lenticular survey of the vegetation, but above all in the double telescope-like opening of the background that slopes down to bluish landscapes, a solution that recalls the hermit landscapes popularized by the engravings of the prolific Sadeler dynasty,” engravings of which we know Scorza was in possession. The presence, justified by virtue of its symbolic value, of the cute little rabbit poking out from under Jesus’ table, and of the robin whose vivid livery stands out against the shadows behind Christ, is symptomatic of Sinibaldo Scorza’s passion for animals: a passion that is evident even from a work such as the Rest during the Flight into Egypt, a fine tempera on parchment where, to the tenderness of the family idyll, is added the liveliness of the pigeons perched on the basket at lower right, of the little donkey tied to the tree trunk, of the beasts watering at a lake in the distance, and of the dog watching warily (of the dog, moreover, there is a study preserved in the conspicuous collection of drawings in the Czartoryski Collection in Krakow, which constitutes the largest known graphic corpus of Sinibaldo Scorza, with about four hundred sheets). The first section of the exhibition’s five, which features the two aforementioned paintings and is intended to investigate the artist’s beginnings, is completed in the opening room with the display of important comparative works, such as a Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Joseph by Master Paggi that is distinguished by thatelegance that will also be a typical trait of his pupil’s style, or a Nativity Scene by Antonio Travi known as the Sestri that is conversely founded on a rougher adherence to the veristic datum.

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Jesus Served by Angels (ca. 1615; oil on canvas, 148.5 x 270 cm; Voltaggio, Capuchin Art Gallery) |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Rest during the Flight into Egypt (c. 1619; tempera and gold on parchment, 15 x 20.5 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe di Palazzo Rosso) |

Sinibaldo Scorza’s painting of animals was based on close observation from life: suffice, as evidence, the episode (which is also an eloquent example of the painter’s sanguine temperament) that saw the then 21-year-old artist injure with a dagger a fellow artist who, by shooting some firecrackers, had upset a horse that Sinibaldo Scorza was portraying. Horses (and, in general, domestic or farmyard animals that the painter could easily obtain) abound in the second section of the exhibition at Palazzo della Meridiana, all dedicated to the relationship between Sinibaldo Scorza and nature. Singular is the magnificent peacock, more than two meters high: a unicum in the artist’s known production (the format suggests that the painting was meant to fill the space between two windows). It is a work that, despite its size, does not prevent Sinibaldo from maintaining firmly those fine miniaturist skills so elevated that they led him to depict his beloved animals with a meticulousness that denotes a highly developed spirit of observation, as well as innate technical skills, evident especially in the virtuoso brush accents found especially in liveries, plumage, epidermis and assorted furs. And if the Two Pigeons with a Thrush strikes the visitor with its astonishing accuracy, the Squirrel also stands out for the skill with which the painter rendered the typical liveliness of the beast, and some small olî (including a splendid Crouching Fox) offer us the opportunity to investigate one of the motives that led the artist to make small-format paintings in which the animal was the undisputed protagonist and often also the only finished element of the composition (note the backgrounds, often finished in a perfunctory manner or even left unfinished): studying morphologies, poses and attitudes of animals for the purpose of building a useful repertoire for the inclusion of figures in larger and more articulate compositions. And to such a more challenging case belongs the magnificent Entrance of the animals into the ark of Palazzo Spinola: as is almost always the case in Sinibaldo Scorza’s production, the biblical (or literary, or mythological) episode represents a sort of pretext for unleashing the painter’s fervid imagination, whose attention, as one might expect, dwells almost exclusively on the beasts. Hence in the painting we find dogs, cats, sheep, goats, turkeys and animals of all sorts depicted with the same attention to detail that Sinibaldo lavished on the “piccioli animalucci,” and above all we find a white horse entering from the right, a figurative invention of Voltaggino’s that was to be taken up by his nephew Giovanni Battista Sinibaldo Scorza (to whom a section of the exhibition is dedicated) in a homologous painting, and by that Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, known as Grechetto, who was probably the greatest of the Genoese “animalists.” his Entrance, one of the highest quality paintings among those exhibited at Palazzo della Meridiana, takes up Sinibaldo’s idea with snappy vigor (the comparison of the three works is one of the highlights of the exhibition).

|

| Wall with animal figures |

|

| Wall with the large peacock |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Two Pigeons and a Thrush (oil on canvas, diameter 21 cm; Genoa, Strada Nuova Museums, Palazzo Rosso) |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Crouching Fox (oil on canvas, 48.5 x 72.5 cm; Genoa, private collection, descendants of Sinibaldo Scorza) |

While paintings in which animals are the exclusive protagonists are a new occurrence in Genoese painting and in fact constitute animport from Flanders, a land where this genre was born on the back of the birth of modern scientific studies and the subsequent lively interest in nature, compositions in which the presence of animals was required as part of a narrative context were already, of course, well within the Italian tradition, but the section of the exhibition investigating Sinibaldo Scorza’s contribution in this sphere is useful for two reasons: first, because as a distinguished scholar like Carlo Bertelli pointed out a few weeks ago in Corriere della Sera, entirely new is Sinibaldo Scorza’s sensibility compared to that of his predecessors. His Orfei che incantano gli animali (a rather consistent strand in Scorza’s production, some significant examples of which are exhibited at Palazzo della Meridiana), one of which was also chosen for the cover of the catalog, remain imprinted not only for the skillful compositional qualities and the already appreciated care lavished on the detailed description of the beasts tamed by the mythical character’s song, but also because, in Bertelli’s opinion, no one before Scorza had succeeded in rendering as clearly the effect caused by the music on the fauna rushing around the cantor: lions bowing their heads, dogs, chickens, parrots and donkeys all turned toward Orpheus in silent listening, birds of prey and various birds of prey interrupting their flight and stopping on the ground recalled by the notes of the zither. It was precisely an Orpheus singing and playing in the woods by Sinibaldo Scorza that was able to become the subject of two madrigals by the greatest poet of the seventeenth century in Italy, Giovan Battista Marino (Naples, 1569 - 1625), on whose ties with Genoa it is necessary to make a quick excursus as they exemplify that peculiar interweaving of art and letters that represents the second reason for interest that emerges from this portion of the exhibition.

The contribution of a man of letters known throughout Europe, such as Marino was, had contributed in a decisive way to the evolution of the Genoese cultural environment at the beginning of the seventeenth century: it is now taken for granted that the Neapolitan poet, during his stay in Turin, between 1608 and 1615 and then again for some time in 1623, had to make frequent trips to Genoa, which led him to forge solid relationships with men of letters and artists. His relationships with poets such as Gabriello Chiabrera, Ansaldo Cebà and Giovanni Vincenzo Imperiale, as well as with artists, are well known: mention has been made of Sinibaldo Scorza, who was probably introduced to Marino through a common acquaintance, namely Giovanni Battista Paggi, between 1612 and 1613 (so hypothesizes Franco Vazzoler in his catalog contribution on the subject), but the important role of Bernardo Castello (one of his Narcissus is in the exhibition) as a fundamental trait d ’union between Marino and Genoa should also be highlighted. An interesting epistolary between Marino and Castello is preserved, which is also useful as testimony about the work the poet was composing at the time, that famous Galeria with which Marino attempted the unusual and arduous operation of somehow emulating the effectiveness of images through the power of verse. The relationship between Scorza and Marino (which, as might be expected, deepened at the time when both were simultaneously present in the capital of the Savoy duchy) is testified not only by the aforementioned madrigals (which are part of the Galeria), but also by the letters that the two exchanged and which attest to the fact that Marino had requested from the painter canvases having for subject matter that same Orpheus sung in the lyrics: at the moment, however, we are unable to identify them with those we know of. These exchanges attest unequivocally to the fortunes of Sinibaldo’s Orfei, who drew heavily, as mentioned above, from mythology and literature for his works: and one of the peculiarities of his recourse to literary sources consists in the fact that Scorza was an up-to-date and curious reader. One would not otherwise explain a work such as the White Palace’s Circe and Ulysses, which introduces the iconographic variant of the dialogue between the two protagonists and men transformed into animals: according to the studies, cited in the catalog, of scholar Astrid Wootton, the invention would have been suggested to Sinibaldo by reading Giovan Battista Gelli’s Circe, printed in Florence in 1549, a work composed of ten dialogues between Ulysses and the animals of the island of Eea, the latter almost all of whom were happy with their new condition after the change they had undergone at the hands of Circe’s spell. And certainly in Scorza’s possession must also have been Annibal Caro’s translation of theAeneid (published in 1581): we highlight how the detail of the dogs following the hunting procession of the queen of Carthage in The Hunting of Dido (“And behold outside armed / With spikes and with knives, to the sound of horns, / Come the hunters, others with nets, / Others with dogs. Has these a great molossus / That one a veltro on a leash, and long rows / Van of followers chained ahead”) has been faithfully transposed by the Voltagian painter onto canvas.

|

| Section of the exhibition dedicated to fables and myths |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Orpheus Enchants the Animals (c. 1628; oil on canvas, 73.5 x 97.5 cm; Genoa, private collection) |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Orpheus Charms the Animals (1628; oil on canvas, 58 x 93; Genoa, private collection) |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Circe and Ulysses (oil on canvas, 43 x 69 cm; Genoa, Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Bianco) |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, The Hunting of Dido (Oil on canvas, 46 x 71 cm; Private collection) |

The last section of the exhibition testifies to Sinibaldo Scorza’s adherence to the genre painting brought to Italy by the Flemish. Despite the fact that in the last years of the artist’s career he witnessed the rise of Baroque magnificence, he remained completely refractory to such instances, by his own precise will, preferring to turn to the equally modern poetics of the landscape, the urban view, and the fragment of everyday life. However, if that of Sinibaldo Scorza must be considered genre painting, we are faced with decidedly original results, because in the harmonious bucolic pictures (see the Landscape from the Museum of the Ligustica Academy) as in the more crowded scenes of city life (the Country in Winter with Market at Palazzo Bianco, for example), Sinibaldo Scorza never shirks his own poetic vein that makes him capable of infusing his own innate elegance into every composition and of rendering the atmospheres of his paintings almost suspended. A “decidedly realistic and everyday way of painting” (so wrote Luigi Salerno in 1976, in an excerpt taken up in the catalog) that connotes landscapes and city passages, such as the Veduta di Piazza del Pasquino, a precious testimony of Sinibaldo Scorza’s Roman sojourn, already pointed out by Roberto Longhi, which in the exhibition dialogues with Lucas de Wael’s seascapes and views of Livorno. The exhibition finds its conclusion, anticipated by a singular Urinating Cow (which will suggest, to visitors used to frequentingcontemporary art, that the Venetian Luca Rento, with his lightbox with a homologous subject at the GNAM in Rome, did not invent anything: Scorza had arrived at it four centuries earlier), in an exceptional crib of painted silhouettes (thus of the same type as the Cow mentioned above) proposed as a surprise for visitors and about which it will be necessary to write more extensively in a subsequent article.

|

| Section with views and landscapes |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza, Country in Winter with Market (c. 1620-1624; oil on canvas, 37 x 55 cm; Genoa, Strada Nuova Museums, Palazzo Bianco) |

|

| Sinibaldo Scorza’s nativity scene |

You enter the exit with the knowledge that you have visited an exhibition that is only seemingly easy: in fact, Sinibaldo Scorza. Fables and Nature at the Dawn of the Baroque conceals a decidedly articulated structure, which allows the exhibition to lend itself to different levels of reading, and that of “Sinibaldo Scorza painter of animals” is but one of many. This is a notable plus point for an exhibition founded on a very solid scholarly project, so much so that the excellent catalog also serves as the first monograph on the artist (there are also cards of paintings not on display). Although the painter is little known and his range of action must be confined to a purely local sphere, we feel confident in saying that the Genoese exhibition represents one of the most interesting exhibition events of the year at the national level: in the admittedly somewhat cramped spaces of the Palazzo della Meridiana (at times one has the feeling of being faced with an overcrowding of works, but their quality and the interest they arouse is such that one does not pay too much attention to them) an exhibition has been set up that, in terms of the number of works exhibited in relation to the artist’s known output, in terms of its ability to frame them in context, in terms of the depth of the project that supports it in terms of its ability to communicate to an audience not necessarily familiar with the art of 17th-century Genoa (of note is the good standard of the explanatory panels which, although only in Italian, offer a very clear basis - and this is not something to be taken for granted - for understanding the exhibition’s themes), can easily compete with the “top” events of the national exhibition season. And this is leaving aside the fact that the exhibition also presents itself as an important basis for future studies on the art of Sinibaldo Scorza and, more generally, on the Genoese seventeenth century. Lastly, as anticipated, the exhibition of drawings at Palazzo Rosso, curated by Piero Boccardo, deserves a mention: the continuous references to the exhibition at Palazzo della Meridiana, the quality and fineness of the sheets on display, and the possibility they offer for framing Sinibaldo Scorza’s training, sources and method make it a unique opportunity for in-depth study, deserving of an equally careful visit.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.