by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 17/04/2017

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition 'Tano D'Amico. The struggle of women' in Castelnuovo Magra, Tower of the Castle of the Bishops of Luni, through May 28, 2017.

Thirty-four years of women on the front lines. Of women who have struggled, are struggling and will continue to struggle to gain rights and improve their own (and often men’s) condition. Thirty-four years of heated passions, of intense loves, of burning desires. Of struggles that ended in historic victories or searing defeats. Thirty-four years of joy, of tragedies, of conquests, of defeats, of unity, of friendship, of quarrels, of pride, of dignity. Thirty-four years of true emotions, felt because one believed in something, and not because they were induced by someone who wants to guide even feelings. Of enthusiastic, happy, mild, somber, cheerful, sweet, sullen, stern, friendly, proud looks. Thirty-four years, from 1970 to 2004: this is the long period told by the exhibition The Struggle of Women, which displays the photographs of one of the greatest contemporary Italian photographers, Tano D’Amico (Lipari, 1942), at the Tower of the Castle of the Bishops of Luni in Castelnuovo Magra.

|

| Entrance to the exhibition Tano D’Amico. The struggle of women in Castelnuovo Magra, Tower of the Castle of the Bishops of Luni |

An exhibition that falls in a special year, because exactly forty years have passed since that 1977 that gave its name to the Movement of protest, struggle and action that Tano D’Amico recounted in several of his shots. Demonstrations, marches, clashes with the forces of order, violence, death. But also hope in the future, trust in the next, attempts to change the world. This is how the ’77 Movement could be summarized, the traces of which in the present are rather difficult to find. Tano D’Amico was there, but not to document. The document is a double-edged sword; the image used as a document is a soulless image that can easily lend itself to manipulation. And Tano D’Amico also reminded this at the opening of the Castelnuovo Magra review: a photograph can take a moment of an unjust reality and perpetuate it forever. It is the most reactionary operation imaginable. So, Tano D’Amico’s photographs tell. A story, a dream. They are photographs that almost never capture the climax of an event or an action: instead, they linger on faces. And underlying this there is also the memory of a practical reason, of when the photographer, as he himself stated in a fine interview with Robinson, at the beginning of his career had neither the means nor the money to reach immediately the places where something had happened. As a result, Tano D’Amico learned “to read history in people’s eyes.”

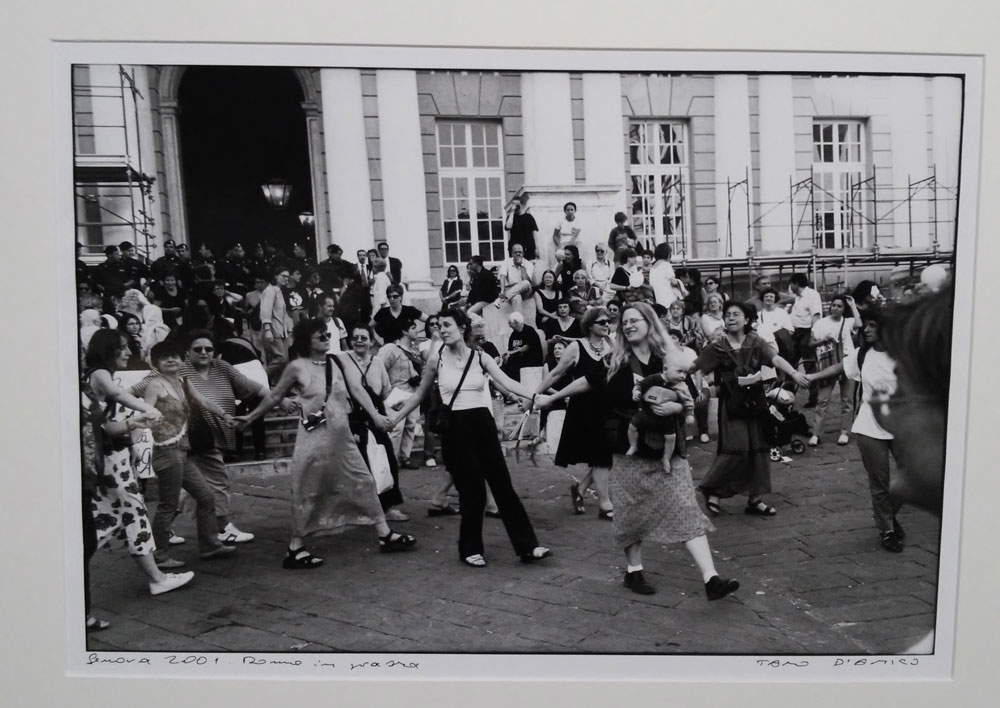

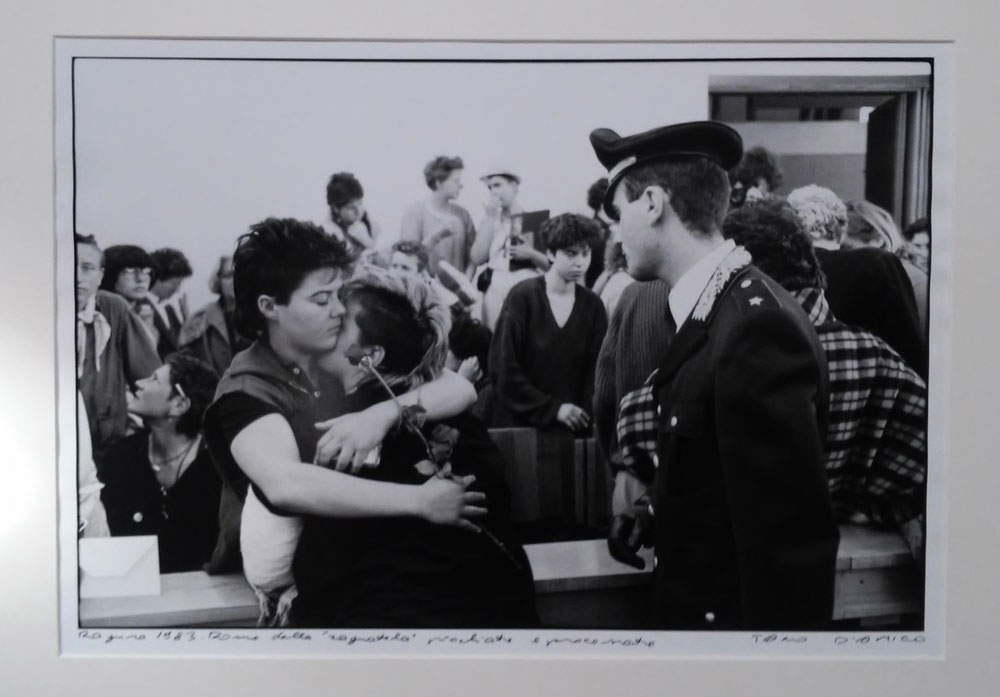

And it is precisely in the eyes of the protagonists of his works that we read the events of this abundant thirty years of our history. The merit of the institute that curated the exhibition (the Fosdinovo Resistance Archives ) is to have followed, in broad strokes, a thematic subdivision that follows the six floors of the Tower of the Castle of the Bishops of Luni. Visitors can thus identify a sort of rough itinerary (because the subdivision in any case is not strict) that can guide them within the women’s struggle that gives the exhibition its title (although one can safely speak of struggles, in the plural, given the multiplicity of battles and the vastness of the period covered) and which, in the exhibition, begins with feminist claims: marches in which the critique of the masculinism inherent in society takes the concrete forms of a monstrous idol accompanied by the words “patriarchy,” demonstrations to loudly affirm that women’s bodies are not objects to be disposed of at will, gyrations and hugs between women of all ages, moments of happiness and conviviality. A kind of introduction, a declaration of intent, and the message is clear: women are active participants in society and never back down, even in the face of the toughest battles. And one of these battles is the one that the women of the Comiso Web fought in the 1980s: they were then trying to prevent NATO from installing a base in the Sicilian town. The embrace between two Spider Web girls under the gaze of a carabiniere during a trial is the image that sanctions the defeat of that experience and opens the section we can imagine dedicated to resistance.

|

| Images with the struggles of feminism |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Genoa 2001. Women in the square |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1975 |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Ragusa 1983. Women of the Web beaten and tried. |

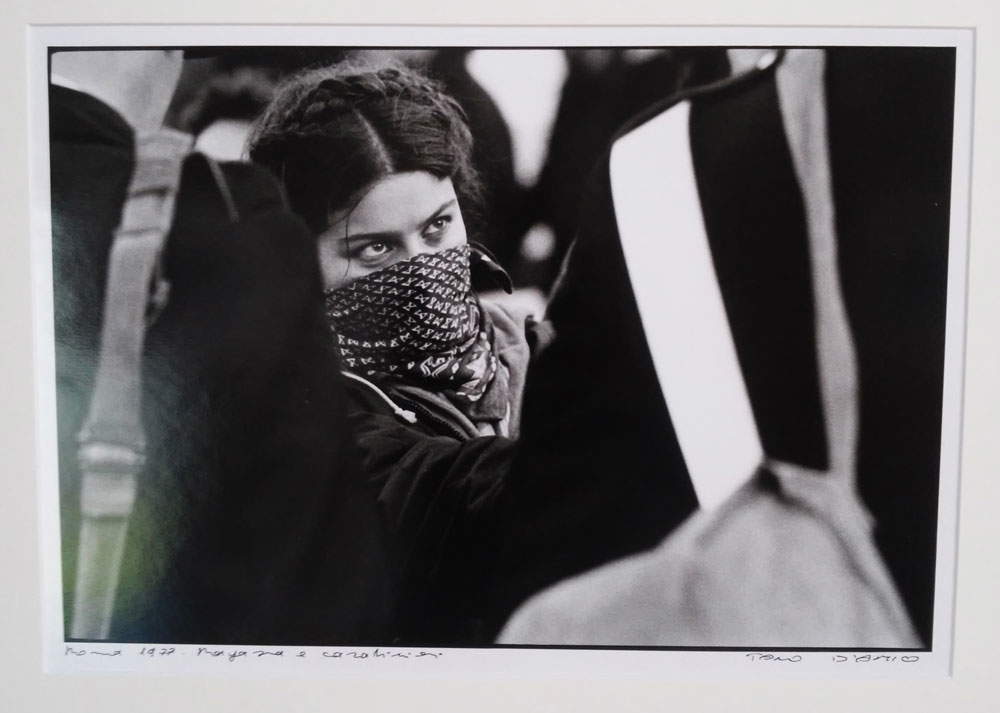

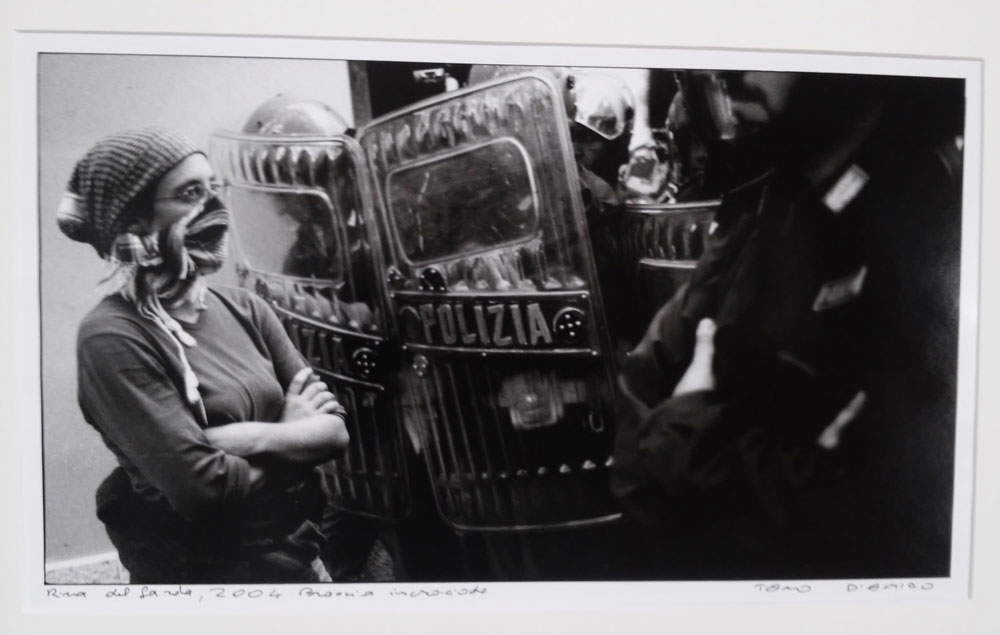

The image-symbol is that of the girl with a handkerchief lowered over her face gazing defiantly at a carabiniere. A photograph that has become (and we can say this without exaggeration) an icon of the struggles of the 20th century: the boundless beauty of that gaze is imbued not only with defiance, but also with pride and passion. At Castelnuovo it is displayed next to an image from 2004, then twenty-seven years later, taken in Riva del Garda: another girl, with a keffiyeh covering her mouth, similarly defies the police, arms folded, as if to say that the fear of being physically attacked during a protest is less than the desire to change society. It may sound rhetorical, but anyone who has tried at least once in his or her life to participate in a demonstration, a strike or, in general, an opportunity to assert his or her beliefs and desires knows that this is not the case. Above all, Tano D’Amico’s women know this: women “protagonists of change, inhabiting and acting in history, full of a pride that often flows into anger, and a dignity that manifests itself as much in pain as in joy, in friendship and celebration, which are the indispensable preamble to a construction of a different self, of a group and choral self-determination,” as Simona Mussini and Alessio Giannanti of the Resistance Archives write in the catalog. There is also no shortage of moments of mourning: one of the highlights of the exhibition is the photo of the sisters of Giorgiana Masi, the student killed in Rome on May 12, 1977 during a demonstration, a crime whose perpetrators remain unknown to this day. A sort of Greek tragedy with the protagonists running in despair toward us who are observing and the co-authors who, behind them, narrate the context within which the heinous affair unfolded.

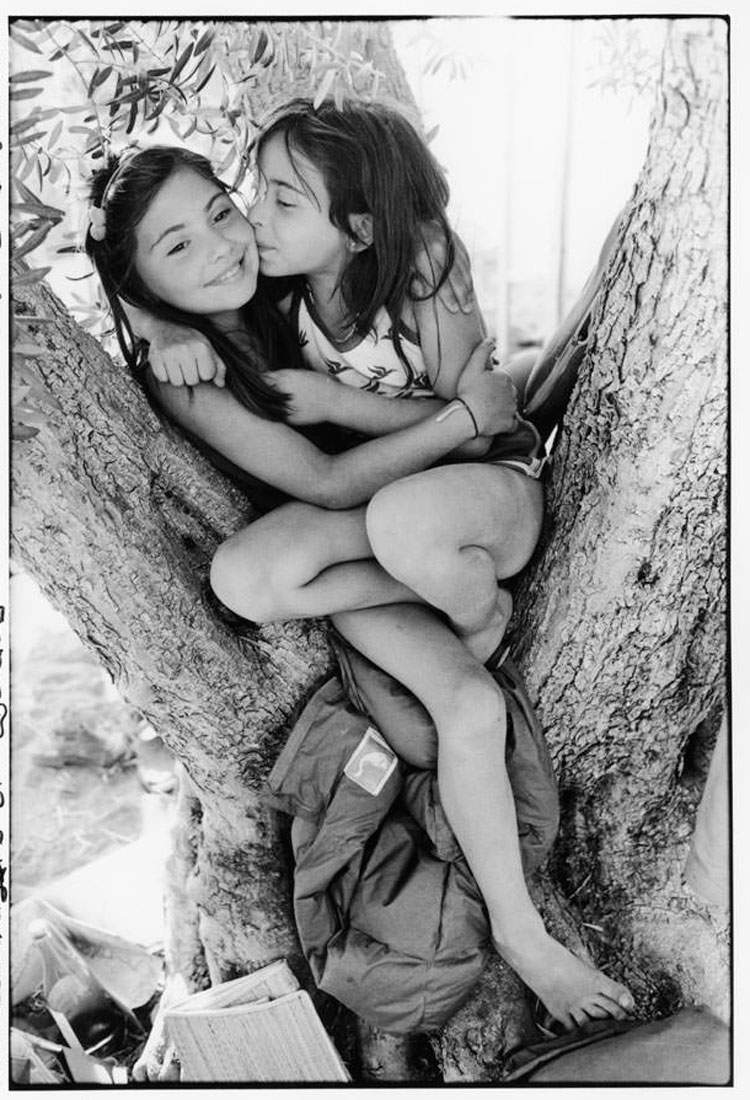

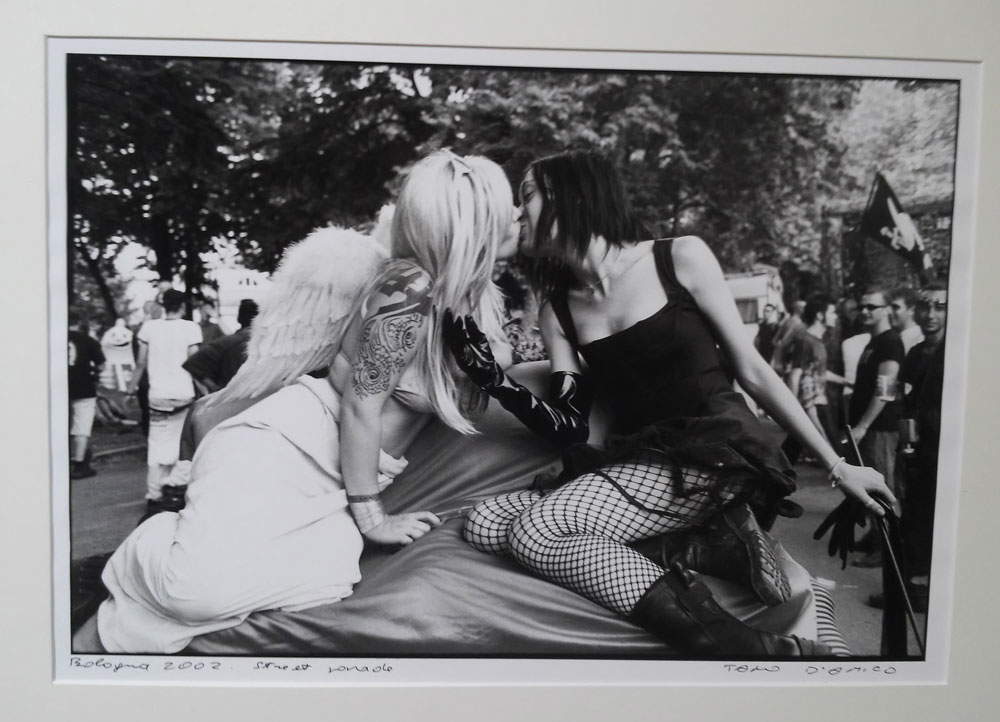

A conspicuous selection of photographs then celebrateslove, the human feeling about which most has been written and debated and whose role is also fundamental in the struggle: without love, passion cannot be ignited. It is perhaps the photographs that strike the audience the most, because they are the ones able to communicate in a way that is least susceptible to interpretation: a girl with a sweet Mediterranean profile who, during a March 8 parade, gently touches the cheeks of a little girl encased in an eskimo from which a chubby, melancholy face emerges, is an image that comes directly, that speaks to everyone in the same way, without the possibility of being misunderstood. And the same is true of the two little girls who, at the 1982 Comiso pacifist camp (the same one from which the beaten and tried Spider Web girls came), climb a tree, embrace each other affectionately and with wonderful smiles exchange a kiss that in the exhibition is placed next to that of the two girls who unite their lips during the 2002 Bologna Street Parade. These are images of rare beauty, photographs that instill hope, shots on which one lingers for a long time and which once imprinted remain indelible.

|

| The comparison with the two women of Rome and Riva del Garda. |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1977. Girl and carabinieri |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Riva del Garda 2004. Crossed arms. |

|

| Photographs celebrating love |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome, March 8, 1978 |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Comiso 1982. At the pacifist camp. |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Bologna 2002. Street Parade |

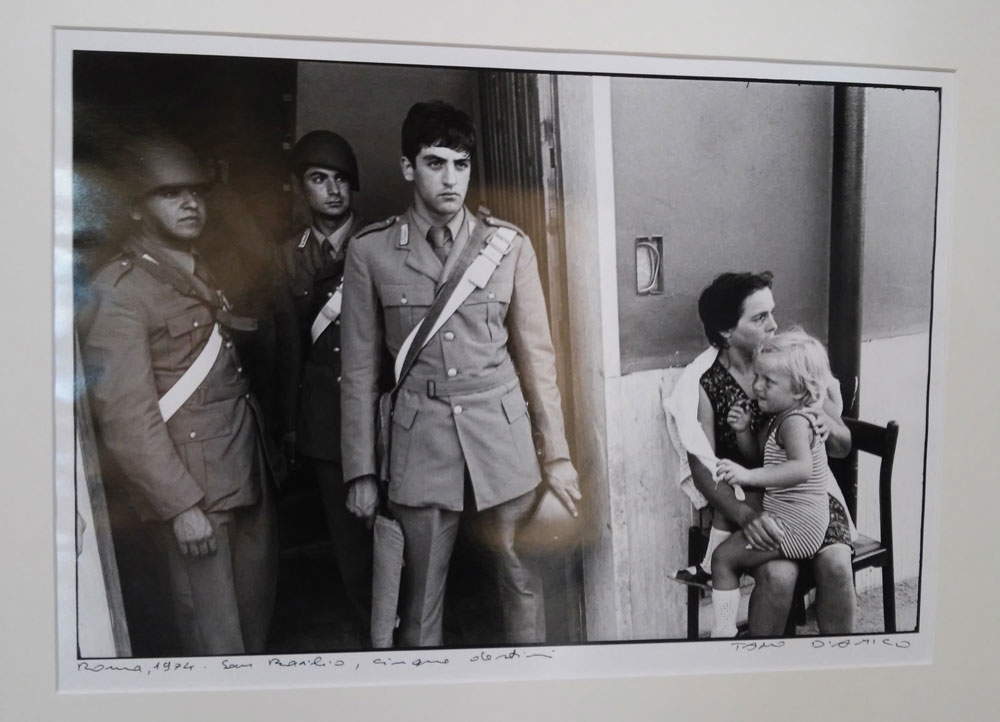

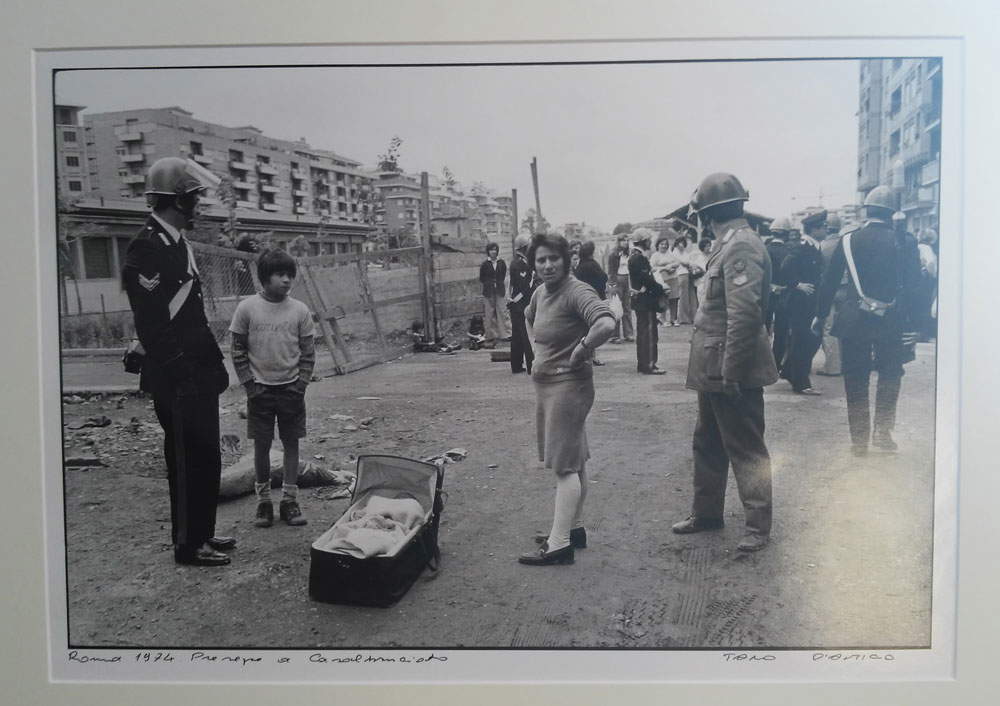

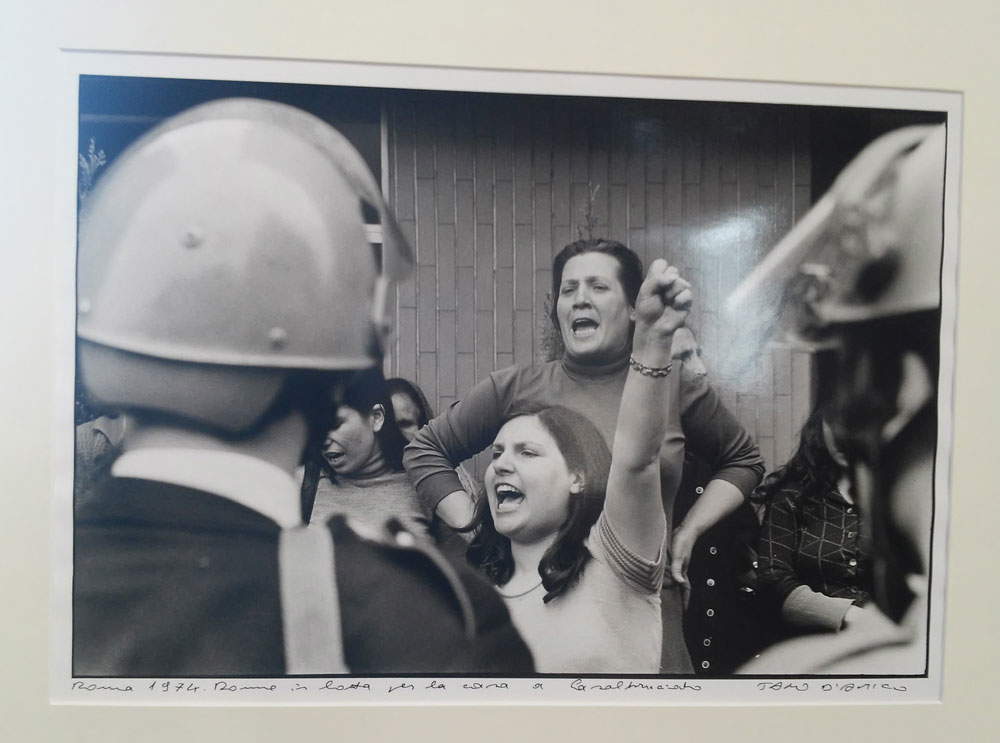

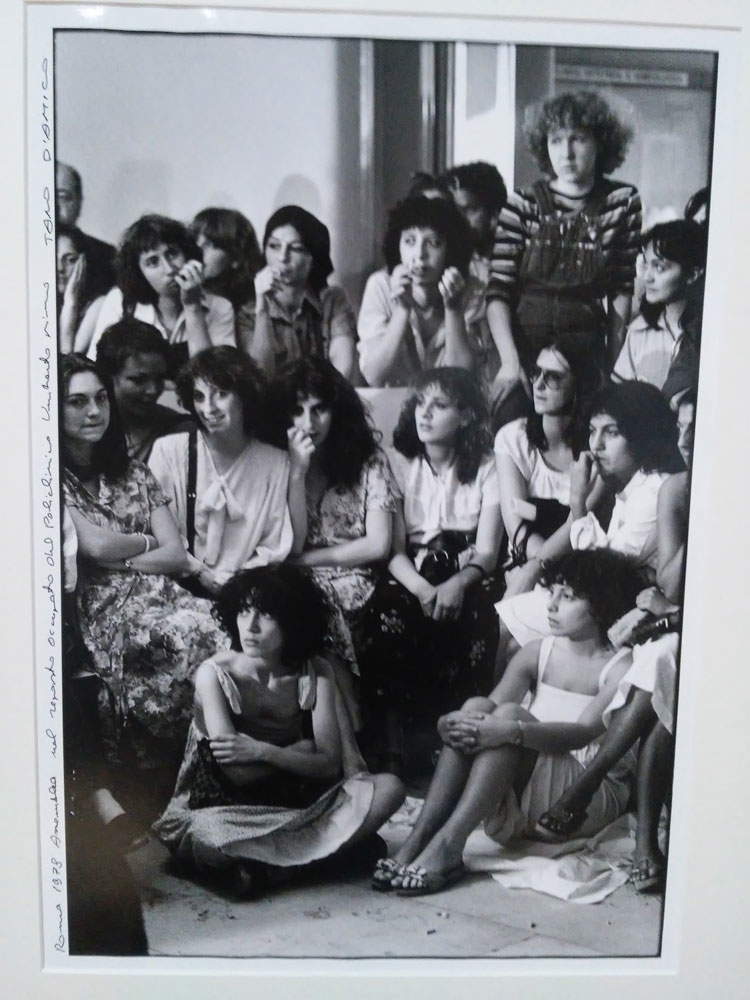

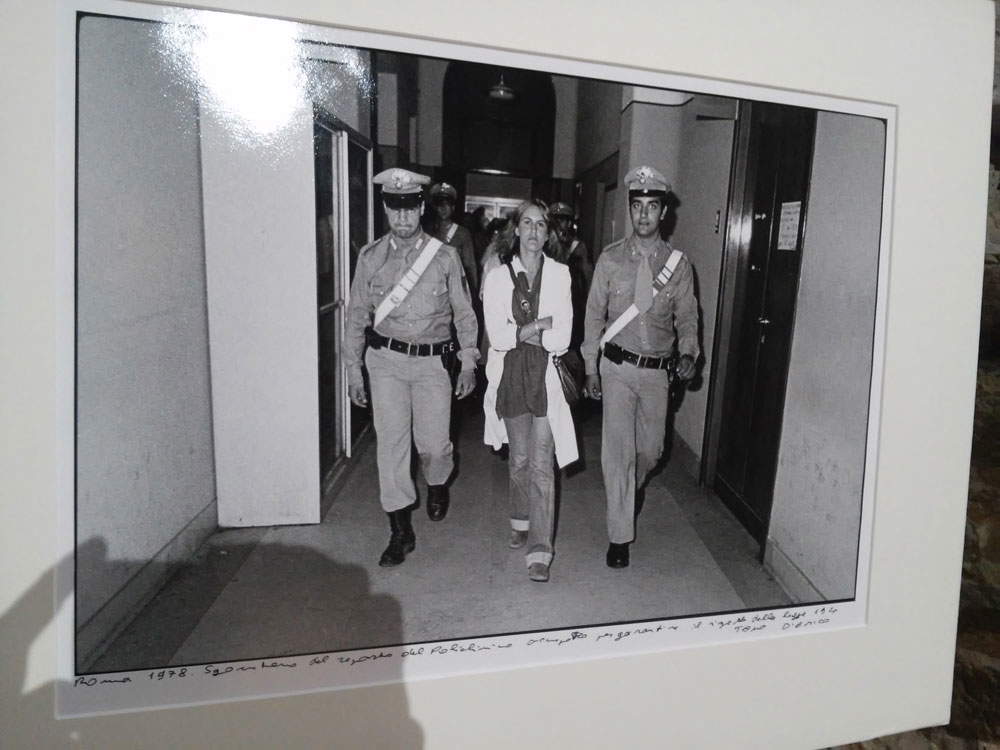

The last three floors are dedicated to struggles for fundamental rights: housing, work, health. The selection opens with a photograph renamed"Five Fates" by Tano D’Amico himself: three army soldiers, a woman and a little girl look around, blending for a moment their existences in the context of the housing riots that broke out in 1974 in the neighborhoods of San Basilio and Casal Bruciato in Rome. Tensions, barricades, clashes with those forces of law and order that often rounded up individuals even more desperate than those fighting against them, women confronting the police, often with peremptory gestures. A woman and two children staging an impromptu nativity scene in the midst of a riot in Casal Bruciato, as if to draw parallels between the suffering of those about to lose their homes today and those who two thousand years ago, according to the narrative, were forced to wander to find shelter. And then smiling faces inside occupied factories, marches to demand equal treatment in the workplace, the assemblies in the occupied ward in 1978 at Rome’s Policlinico Umberto I to organize a space in which to worthily and warmly welcome women who needed to terminate their pregnancies in accordance with the newly enacted Law 194, the subsequent eviction.

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1974. San Basilio, Five Fates |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1974. Nativity scene in Casal Bruciato |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1974. Women fighting for housing in Casal Bruciato. |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1970. The last laundress of Trastevere. |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Milan 1973. In the occupied factory |

|

| Photographs of the occupied polyclinic |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1978. Assembly in the occupied ward of the Policlinico Umberto I. |

|

| Tano D’Amico, Rome 1978. Eviction of the occupied Policlinico ward to ensure compliance with Law 194. |

At a time of full regression in the area of rights, and particularly women’s rights, the importance of an exhibition like the one in Castelnuovo Magra is crucial. Many of the achievements of the struggles recounted by the exhibition have undoubtedly gone up in smoke, but the images remain a powerful means of stimulating change. This is the main goal of Tano D’Amico’s photography: to “capture a moment of change.” Consequently, photography is but a starting point: “to restore meaning to life, to build a collective memory, to rewrite all and together a new history,” as per the conclusion of the catalog’s introductory essay. A starting point that spurs us to go in search of beauty: identifying beautiful images is, for Tano D’Amico, a way to open our minds and souls to a new or different vision of the world. And at the basis of his shots (and, of course, in the Castelnuovo Magra exhibition) it is possible to find this extraordinary beauty that can guide us to seek further beautiful images. “Beauty” is today an overused term: therefore, we use it very sparingly in this magazine. But in front of Tano D’Amico’s images, it is not possible not to speak of beauty: because it is not that empty, futilely aestheticizing, banal beauty, good just for the vacuous and inconclusive rhetoric of certain politics or for the ephemeral and exhibitionistic ecstasies of those who think that art should remain detached from reality, confined in a muffled mode of cuteness and good feelings. No: the real beauty, the extraordinary and meaningful beauty of Tano D’Amico’s photographs dwells elsewhere. In the mud of Casal Bruciato, in a dusty Sicilian campsite, among the batons of the celerini in the squares of Rome, in a squatted shed in the Milanese hinterland, in the faculty assembly of a university. And for a few weeks he will find hospitality within the walls of the Tower of the Castle of the Bishops of Luni.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.