Edinburgh becomes the center of a journey into16th-century Italian art for a few months. At the King’s Gallery at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the Drawing the Italian Renaissance exhibition opens today, Oct. 17, through March 1, 2026, an exhibition curated by Lauren Porter that brings more than 80 drawings from the Royal Collection to Scotland for the first time. Among the 57 artists featured are names that have marked the history of art: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raphael Sanzio, and Titian Vecellio. Some 45 of the works on display had never before been shown to the Scottish public, making this the largest exhibition of Italian Renaissance drawings in Scotland for more than half a century.

The exhibition comes to Edinburgh after its success in London, where it had received a very positive critical reception. It aims to show the variety and function of drawing in the Renaissance, at a time when this tool assumed a central role in design and experimentation. In the room are preparatory studies for altarpieces and paintings, designs for sculptures, but also elaborate sheets made as gifts. The drawings, by their nature ephemeral, were often discarded once the task was accomplished, and only a small portion have come down to us. Their survival within the Royal Collection has ensured that they can be preserved in a condition that allows them to be enjoyed today in almost the same way as they might have been at the time of creation.

“This is a rare opportunity to share such a large number of Italian Renaissance drawings from the Royal Collection, over half of which are being shown in Scotland for the first time,” says the curator. “Being works on paper, they cannot be exhibited permanently for conservation reasons, which makes the exhibition a unique opportunity to get closer to the thinking of the artists who conceived them.”

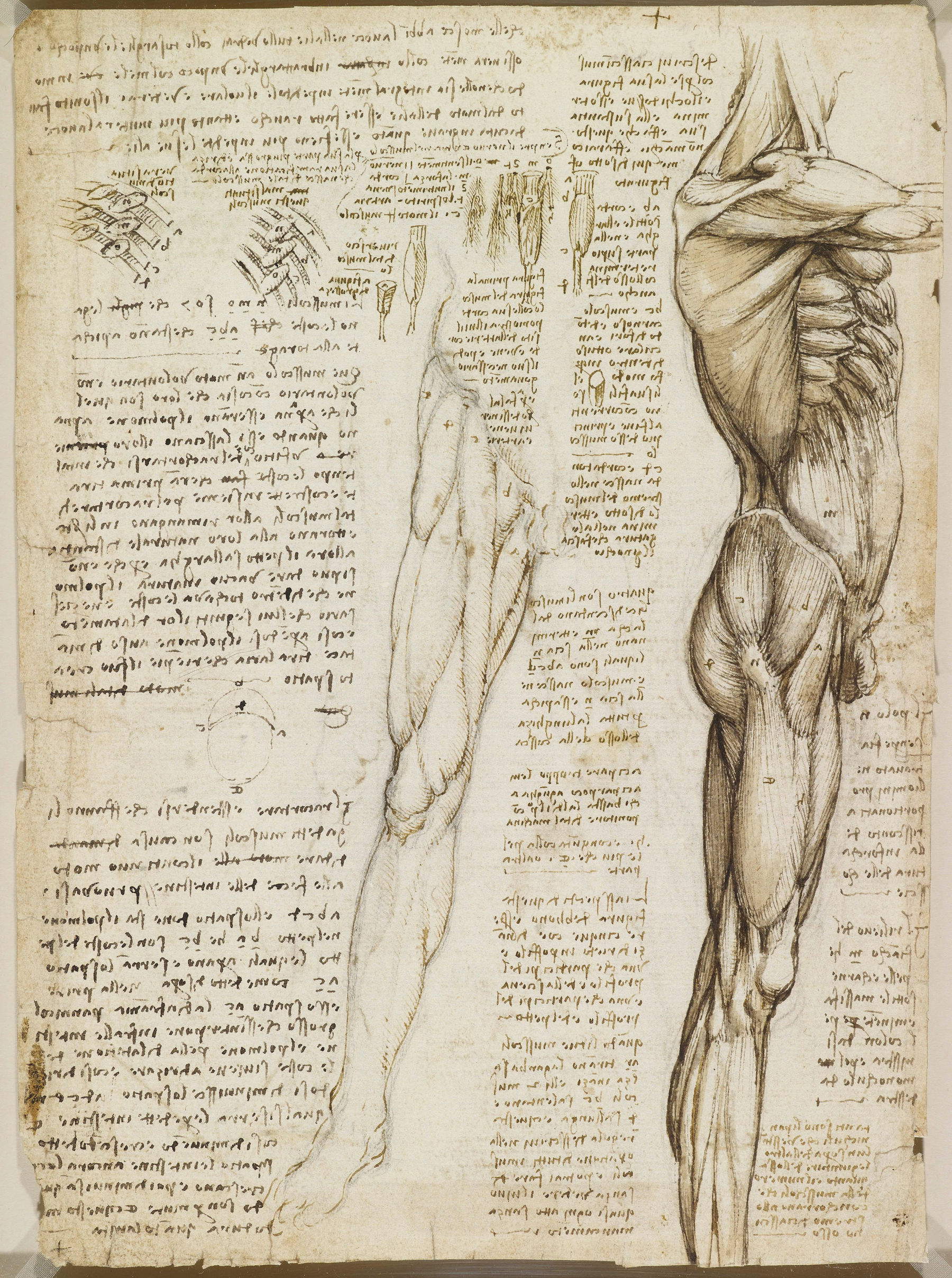

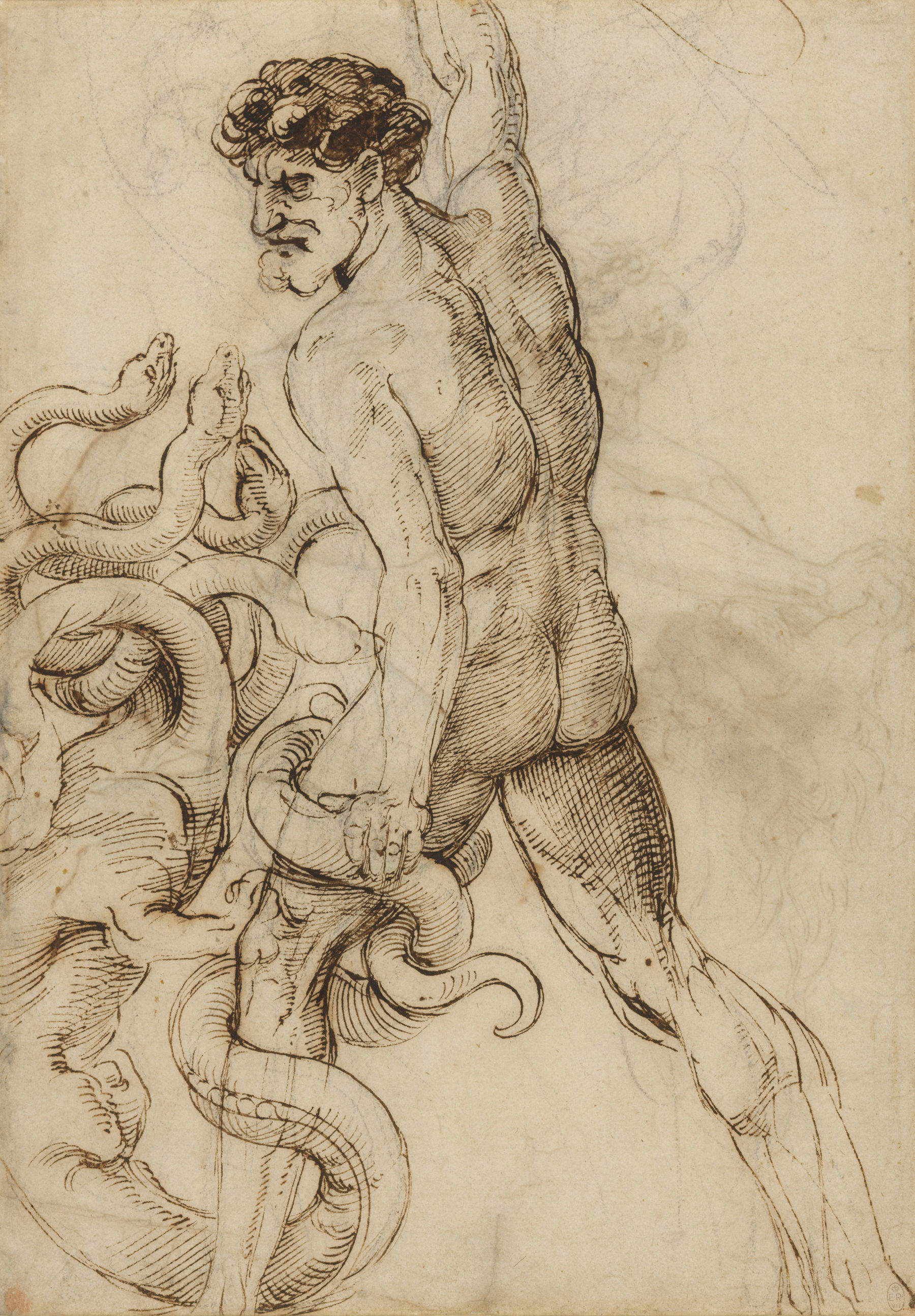

The exhibition is not limited to looking at the past. The gallery has launched its first artist residency for the occasion, in collaboration with the Edinburgh College of Art. Two local artists, Phoebe Leach and Dette Allmark, both trained at the same institution, are working on new works directly in the gallery spaces, confronting Renaissance masterpieces and producing work that will form an in-progress installation, visible to visitors. The public is also invited to try their hand at drawing, with materials made available within the rooms. Among the most important pieces is a sheet by Leonardo da Vinci, dated around 1510-11, with anatomical studies made after a dissection. The drawing, on both sides, depicts the muscles of the human body, accompanied by notes penned in the artist’s usual mirror writing. Another work related to anatomy is that of Michelangelo, who had conducted dissections since his youth. On display is a pen-and-ink study of his male torso, probably derived from a wax model he himself modeled, and a black chalk drawing of the risen Christ, in which the energy of the figure in the act of emerging from the tomb can be felt.

The itinerary also includes two studies by Raphael: a drawing depicting Hercules in the act of killing the Hydra and a red chalk study of the Three Graces, a rare example from the period in which the artist uses a nude female model as a reference. Mythology, a recurring subject in Renaissance workshops, is well represented with lesser-known works, such as Paolo Farinati ’s design for a fresco featuring the goddesses of fruit and agriculture. In the drawing, presented for the first time in Scotland, there appear written instructions from the artist for his assistants, with instructions on the proportions of the figures, which were to measure about a meter but with the freedom to adapt them during the execution. Another drawing attributed to Titian depicts an ostrich, probably taken from life, while Leonardo also appears with a curious design for a dragon costume, with two men hidden inside, similar to a sort of pantomime horse.

The exhibition also features a series of portraits and head studies that illustrate the variety of subjects and materials. Particularly striking is the contrast between the deformed, suffering face of a grotesque mask drawn by Michelangelo, possibly intended for a sculpture, and the portrait of a curly-haired young man executed by Leonardo in red and black chalk, both exhibited in Scotland for the first time. Great attention has been paid to the restoration of the works. In preparation for the London exhibition, restorers from the Royal Collection Trust spent about 120 hours preserving Bernardino Campi ’s cartoon for an altarpiece of the Virgin and Child. The work, composed of four sheets joined together and used to transfer the drawing to the pictorial panel, had been glued to a canvas that had deteriorated. The restoration work required the detachment of the paper and the reconstruction of the most fragile parts, reduced to a thickness comparable to lace.

The variety and quality of the drawings on display give a clear idea of how, in the Renaissance, drawing had expanded its function, becoming not only a technical tool but also an autonomous language. Among the works considered the pinnacle of this production is Michelangelo’s Bacchanal of Putti, executed with extreme precision and arrived in perfect condition. The exhibition is also accompanied by a series of public initiatives: drawing workshops and workshops dedicated to families, yoga activities inspired by the movements of Renaissance figures, meetings with illustrator Mark Kirkham, known as the “Edinburgh Sketcher,” and lectures by curator Lauren Porter. There are also evening events with music and crafts, as well as free short talks every Thursday.

For the public, access is facilitated by different ticket formulas. The King’s Gallery Ticket Scheme, launched in 2024, provides entry at a nominal price of one pound for Universal Credit and other benefit recipients, extendable to up to five family members. Additional reductions are available for young people and families, as well as the option to convert standard tickets into an annual pass with unlimited admissions.

The accompanying publication, Be Inspired: To Draw Like a Renaissance Master, combines practical drawing exercises with spaces for personal sketching, with an introductory essay by Martin Clayton, head of prints and drawings at the Royal Collection Trust. With Drawing the Italian Renaissance, the Scottish capital thus hosts an event that allows the public to come into direct contact with the creative center of an era, bringing the Royal Collection’s holdings into dialogue with contemporary art practice.

|

| Renaissance on display: from Leonardo to Michelangelo, drawings in Edinburgh |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.