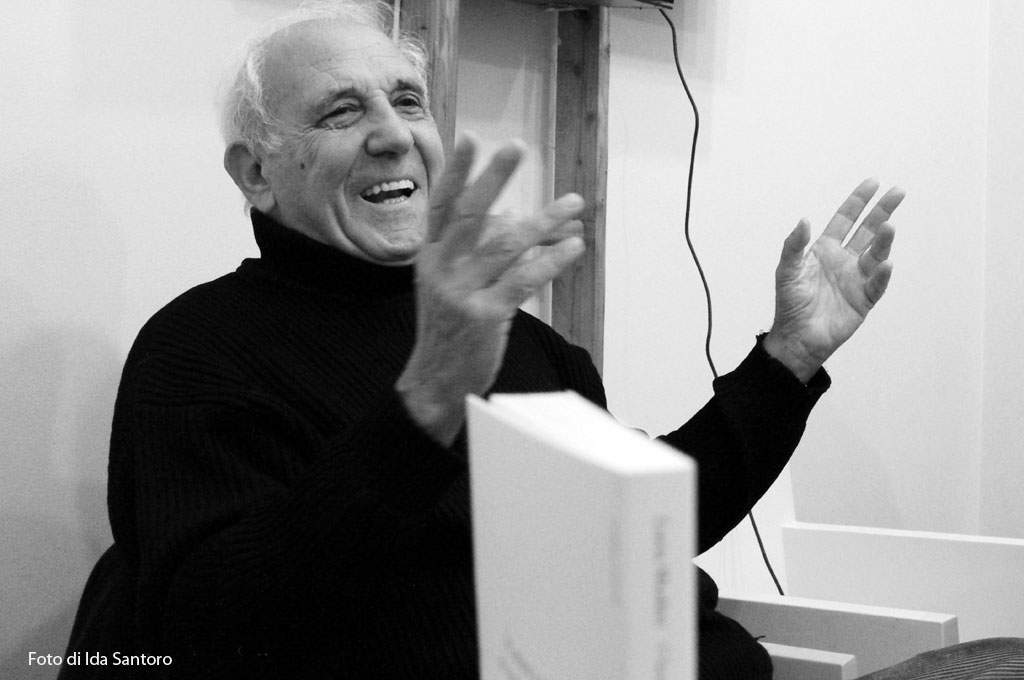

Uliano Lucas (Milan, Italy, 1942) is one of the protagonists of Italian and European social photography, active for more than sixty years in Italy and around the world, with reportages that have documented all the greatest changes that our country, and many other places around the globe, have experienced from the 1960s to the present. What does it mean to be a photojournalist? How has photography helped change the world? Is there still a place for photojournalism today? The answers in this interview, originally published in Contatto Radio, on the occasion of the exhibition Uliano Lucas. Other Voices, Other Places, on view until May 5, 2024 at Carrara, CARMI museum. The interview is by Simone Lazzaroni.

SL: Let’s break the ice right away: photojournalist, photographer, artist... ?

UL: I would say photojournalist. I have always felt like a photojournalist, even if the term in Italy is not well understood. I have worked within the communication system, that is, newspapers, so the photographer is someone who does still life, does fashion, does other things, while the artist is another story. The French have an extraordinary term, photographe de presse, meaning “photographer for the press.” Today, on the other hand, I cannot call myself a photojournalist, I prefer to say photographer, in the sense that I have entered that age where I no longer run....

By the way, at that time you were a freelance photojournalist, so for that period maybe something also quite unheard of...

There were several of us, because Italian journalism allowed this figure of the freelance photojournalist, that is, a person who produced the images, built reports, went to certain places, countries or in the news, and then there were then many magazines, of various cultural, political and other tendencies, and they sold the report. I must say that this was also possible because most of the rotogravures did not have in-house photographers, so the system relied on photo agencies and then these freelance figures. We had some extraordinary freelance photojournalists, people who went down in the history of European and even international photography.

What is the difference between being a freelance photojournalist and an editorial photographer? Maybe there was also the possibility of being much freer?

Yes, I chose to be a freelance photojournalist precisely to manage my freedom and also my time. And I was reflected in a number of newspapers politically and culturally, in the sense that I was a reporter, but I never gave a photograph of myself to a newspaper like Gente or Oggi. I mean, I was avowedly, and I am, a libertarian communist, and I defend that position: it means and has meant going and photographing or going and doing reportage that I chose, that I decided, that I constructed, so it’s a different story than many others and that of a journalism, that of the magazines, with circulation of millions (it was like today’s television), with editors who were cowards, reactionaries (Italy was very backward): it was power publishing, so the vision they gave through photographs was a vision of an Italy that was completely false. If one goes to leaf through these magazines one finds the Italy of the physical majoratas of Gina Lollobrigida, of Padre Pio, of royalty. The imaginary was what Berlusconi’s television later made its own. An imagery with consequences that they then felt, because they did not inform us of what the true state of our country was. The problem then was to make an information or counter-information that told, or tried to tell, the world of the invisible, the world of reality, the world of what was around us.

Is that a profession that is no longer there?

No, it is no longer there, because of the extraordinary transformation of communication systems, in which we Italy come late. Digital, entering in the 1990s, finds us totally unprepared and has wiped out the print media and the whole information system. Now the management of the news is left to five or six international agencies that determine our point of view: the problem of visual, televised, written communication today is a problem of democracy and we are unprepared. Having said that, then it wiped out all this journalism of ours, however, a problem of inventing something else was not addressed. So even in this photographically we are 80% dependent on what is bought from foreign news agencies.

A digital revolution, then, with perhaps not a positive meaning?

No, in my opinion it is positive. The problem is that we have failed to manage it. It is a disruption that, however, in some countries they have managed to manage, while instead within Italian visual communication there is a backwardness due to the fact that part of communication and, I must say, also of the publishing world, has always been tied to a political power.

Let’s go to the beginnings: how did you come to photography? How did you get into photography?

Mine is the story of a young man who, by a series of circumstances, enters a magical, wonderful, fairy-tale world, the world of the 1960s in the shadow of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts, which was then a remarkable cultural center (the painters of the 1940s and 1950s and all the avant-garde movements had just come out there), and he frequented a series of small clubs, bars and dairies in the center of Milan, on Via Brera, including one a bar that later became a legend, the Jamaica. Entering this place, a large tiled room, I would hear talk that was new to me, that is, I would hear people discussing surrealism, Dadaism, cinema, neorealism, American cinema, pop music. Young people, old people, elderly people, people with berets which was the typical headgear of the bohemian. I was fascinated, I was 16 years old, by this this constant discussion. I was there days and days and then I said, “This is my university.” And then it was my office, my home, my work, where I met really extraordinary, generous, incredible characters as truly generous, incredible is always the true artist. Every day I was hearing, doing, learning, trying to understand music, theater. I grew up together with Piero Manzoni, with Castellani, with the avant-garde, with Arbasino, with Bianciardi. The names are many, and many became then friends who, however, also sent me to classes, sent me to study at the Accademia Braidense, in the morning we would leaf through the newspapers, and within this solidarity, these discussions, these acquaintances, my interest in cinema and photography increased. But when there was the time then to choose what to do when I grew up, I realized that being interested in painting or anything else would be a con. Writing was not for me, I was more of a reader, I realized that cinema fascinated me (I used to go to the movies all the time with my friend Piero Manzoni) but it is an industrial system for which I was not capable ... and I was also a very rebellious kid and I understood (and they made me understand) that a camera put in the hands of people like me could be a dialogue with myself. So I realized that there was a little space that I could take advantage of and that my photographs were already looked at with interest, so I started making photographs that were impressions of people and situations that were around me.

Then ’68 came along and, although it is trite to ask, was there a turning point?

’68 surprised me, I must say, already formed. In the sense that in the previous years I had been around this world of artists and was freelancing. The anti-authoritarianism of ’68 found me at a time when I had a good cultural and political background. The crux, however, is that ’68 needed new photographers, that is, any revolution needs new protagonists in the sense of storytellers: in writing, in photography, in cinema there was a new language (Godard is the example), and in the end the problem was not to photograph a moment of the young people who were in the university assembly and whatnot, but it was to tell this explosion that from the working-class union world reached the middle school kids who were becoming aware. So it was a new kind of photography, a new way of reasoning, a geometry of forms, going inside with feelings. And I and a couple of other photographers did that, we always did it as freelancers, as independents, and I have to say that we still managed to tell this this spirit as opposed to agency photos that were the banality to sell the photo.

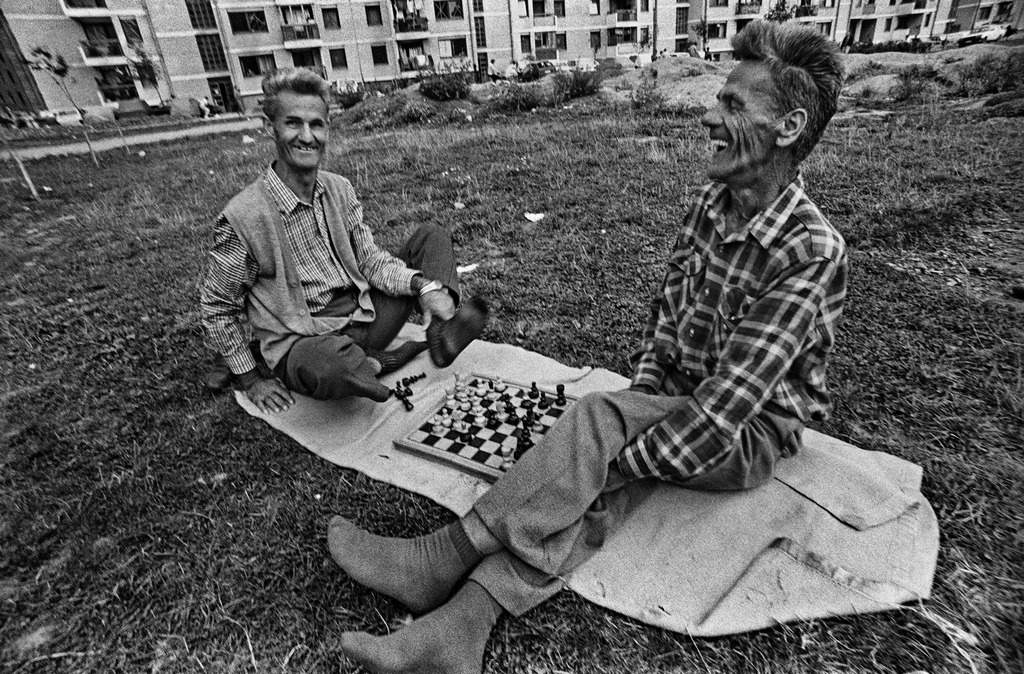

I saw some photos that I would call very intimate, in homes, even during the preparation of lunches of dinners. In an interview you mentioned that to achieve this you had to first get in touch with the subject, create a relationship. In many cases even a friendship was established. And this is something that another colleague of yours, Tano D’Amico, also said: this relationship that was created with the subjects of your photos.

Yes, because it was still fundamental, in the sense that you were photographing an invisible world that had never been told, or had been told by the neo-realists, but in a very banal way, while instead there in front of you you had first of all a person with his dramas, his existence (and they were often dramatic existences), and then they were people who had come from all over Italy because there had been an economic miracle: emigration had really filled in gaps and stories, and emigration is not just manpower, but also new cultures, new foods, new flavors, new songs. There was a whole world that was changing: you had to tell about it. Telling the story of the procession parading with the front rows was something that could work for the Communist Party newspaper or the extra-parliamentary left newspapers: the problem was to understand who was in there, in the procession, and if you, instead of being in the front, entered the procession, you found a world that involved you and fascinated you, the women who were talking, the women who were whistling, the women who were shouting, the people who arrived in the center of Milan, of Turin, looked at these eighteenth-century buildings and were stunned because they had never arrived in the center of the cities. To give you an idea, then, the problem was not so much to understand inside the factories their working world, but to get inside their working-class homes, with all the drama of their existence and also their wages. It was seeing them going out on bicycles, then at one point on wasps and then on Lambrettas, on buses, in short getting inside their lives and becoming their friends. I remained friends with so many of them, even now, because I discovered a strong humanity that was only relegated to a ghetto that was the working world, the blue-collar world. The photos that came out and were published by newspapers such as L’ Espresso, L’Europeo, Tempo, that is, important newspapers, finally allowed a middle-class reader to see another world that was also a Sunday in a working-class home. There were millions of people who had other paths and whom no one had ever deigned to interview and tell about, or if they had, they had done so through the eyes of a petty bourgeoisie that saw a zoo.

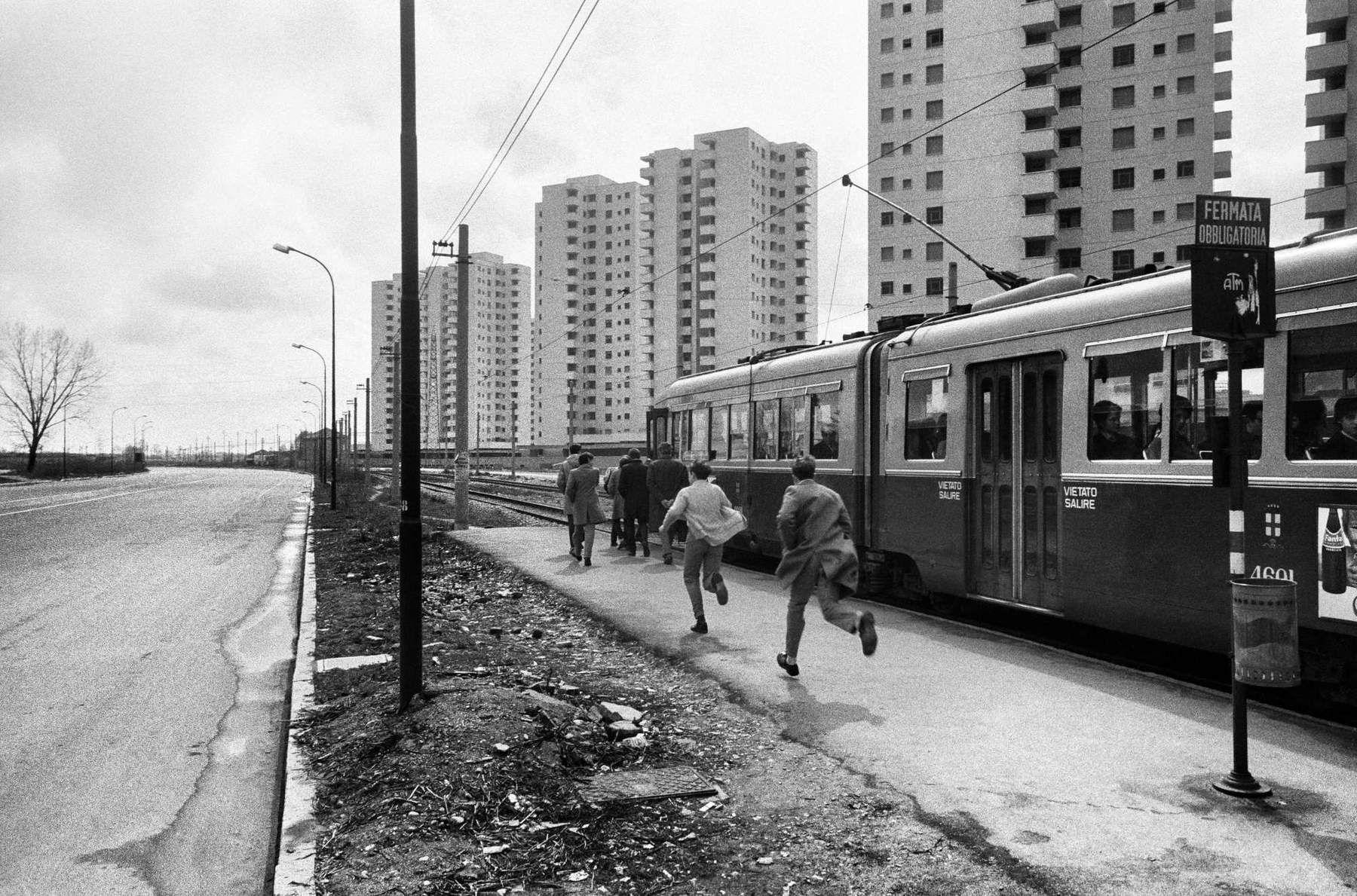

Let’s come to the exhibition: it was organized in seven chapters, seven topics, seven macro areas of his production. The first one is Milan changing 1960-2018. How has Milan changed?

Well, it has changed, it has changed totally. In the sense that, as Cesare Zavattini used to say, you realize that it is a city that eats itself, it is cannibalistic, you want also because of the high cost of land and other things, but nevertheless it changes continuously and completely, so it is a change not only urbanistic, but also of the people in it. It means then going into the houses, going into the courtyard and realizing that the public houses have finished their function, but they have been bought by landlords so they have become something else, the kids no longer run in the courtyard because there is a sign that says it is forbidden to play, private property has prevailed, there is no longer solidarity, but above all it is the times of the city that have changed. It used to be that there were dozens and dozens of sirens calling the three shifts in factories or factories, now there are not. So the times in which the city lives, the time in which the city produces, works, have changed, as have the relationships. And then trying to understand it was very difficult, because the idea of the city was the old working-class city, Sesto San Giovanni, the myths of the struggles, there was a city with young people who were inventing something every day. And then, more cities and more situations: so this immigration from the South that I mentioned before has meant about 3 million people coming from the South to the North and going to Europe in the space of 20 years, it’s a figure that is unbelievable, the great history of the South of Italy of millennia is burned in a very few years. These brought more, though. And then the first foreign nationals arrived, so the photographs that you take at the Central Station of the arrival of the emigrants and the famous Southern train, as Ciampi said, with the photographs of these women dressed in black, with cardboard suitcases and whatnot, 15 to 20 years later they have become the photographs of a world of Maghrebi people who are the same, there is no difference. Visconti’s film Rocco and his brothers today you could remake it with “Ibrahim to his brothers,” so the only difference is that the others before had an Italian passport, while these today do not. And you photograph just the transformation that starts from the Maghrebi or Egyptian migrant that you photographed in the beginning and then over the years, you photograph him in his home for the first time, you photograph his wife joining him, him working in a night bakery, the well-being of his children no. You photograph all of that, then you move to the same council house and you go to see the old worker friend who is now retired, you go in and you see this Alfa Romeo pugliese who has worked all his life and still has the portrait of Gramsci or Stalin, then you open a door and instead you find the big poster of Di Bossi because you have entered his son’s room and you see the change. That’s what change is, and only by going on the spot, telling, walking, talking or managing relationships, can you understand this submerged world coming out into the open. The problem is that you used to have the big newspapers publishing you so the work came out. Today you can do it, but then it stays in the drawer.

The second section of the exhibition is entitled Dreamers and Rebels 1960-1976.

This is the chapter that recounts the anti-authoritarianism of ’68, leading up to the years when this drive ends and another history of the country is entered. And it’s really the great utopia (which was also mine), because you were not just a citizen of this country: you considered yourself a citizen of the world, that is, antiauthoritarianism was in Warsaw as it was in Japan, it was against the Vietnam War as it was against the imperialism of the British... It was an international story. It was the young man who wanted to enter another history. In Italy it was more pronounced, because being a backward country in the capitalist system and in production, all the problems that before were under the carpet (problems of democracy, problems of rights, problems of a patriarchal country, a bigoted country, a cowardly country), they explode on you, so here is divorce, here is the ’worker in the factory and his rights, here are the youth against the barons, here is feminism. An Italy that wakes up and imposes a turning point, represented by civil rights, the demilitarization of the police, the abolition of military service, the end of asylums. I could see, in the 1970s, middle school kids taking to the streets, people beginning to understand rights, and going to demonstrations, women in fur coats in front of the building at Milan City Hall, shouting that they wanted daycare centers, and they were women of the great bourgeoisie, the middle class, the underclass. By now, who is going under City Hall today to say, “Excuse me, we want kindergarten”? It takes a very high civic consciousness. Then all this resulted in another story that was terrorism, which I did not photograph and refused to photograph.

The third section is Work and Jobs.

The difficulty of an independent reporter is to go into factories but also into lawyers’ offices, to photograph, to tell: nobody went in, nobody gave a damn about these 10 million people working. Then I realized that telling about those places, where there was strong socialization, unionization, and together hopes, was also crucial for the historian of the future, that is, to have material, to know what a factory like those of big companies like Alfa Romeo or Fiat, with 10-15.000 people working there, they were cities with not indifferent rhythms, where there was suffering, to know what it was like to live there for a southerner who had just arrived and was still baked from the South in his face. It’s not like you could just take a picture of the assembly line to understand the rhythms, the times. No, you would get permits to enter (even if only in some pavilions, and not in others) and you would be there for days and days and you would be able to tell or try to tell, even with some difficulty in publishing, because the owner had the myth of the factory as a very clean place, while the myth of the left was the exact opposite. Yet there were middle ways: it was the people who then, after their shift was over, would take the bus and go to the outskirts of Turin or the outskirts of Milan and arrive home tired with their problems. To understand this way you had to master it, and it also meant going to urban planners, to sociologists, photographing a neighborhood. It’s not like you just walk through a neighborhood: you need people to point you out and explain, so you go to the priest, to the trade unionist, to the social worker who is crucial in these kinds of reports, because he knows where the misery is, where the poverty is, where the elderly are, he has a lot of information for a reportage that you then construct according to your skill and sensitivity, however, always thinking that it is not that you make photographs for history or for the future, you make photographs for today. With photography you rededicate life to the gazes of others. And that’s why photography is extraordinary, a wonderful thing.

The fourth section of the exhibition has a very strong title, Total Institutions.

At that time the institutions in our country were somewhat reactionary. They were also violent centers of power: I’m thinking for example of psychiatric hospitals, the Basaglian story, these scientists, doctors, psychiatrists who made a struggle with exceptional texts. And it was not just an Italian problem, because the psychiatric struggle was European, other very famous psychiatrists like Cooper tried to do the same thing as Basaglia. There were more than 100,000 people imprisoned, without rights, inside these hospitals, they were there as in punishment, it was the ballast of society. So you were going into closed, inaccessible places. For those few photographers who managed to get in there (I’m thinking of photographers like Carla Cerati or Luciano D’Alessandro) it must have been heartbreaking: was anything like that kind of dehumanization ever possible? So here was a civil struggle, a civil struggle that then had a photograph that allowed the enlightened progressive bourgeoisie newspaper, the people who were opening the Espresso, to feel shame. So he began to support the Basaglian movement, which was a struggle not only to close asylums (this is also the address of the World Health Organization to close asylums, even today, because in other countries asylums are still used as a political weapon, for example in Russia or in certain African countries), but it represented a time for change, for change. And it was not a one-day struggle, it was a struggle against an institution that lasted about ten years. The problem is that I then did not stop. When the asylums started to be closed, I tried to understand where the inmates, the users were ending up, I tried to understand the cooperatives that were coming up, the new problems of mental illness. Another institution was the military: the military institution for the older generation meant 14 months or 12 months of useless military service. You were at the mercy of ignorant marshals or dull-minded officers and guarding a can, that’s all you had. There was some discussion about that and then I followed the military institution and also the rhetoric of military education at length, i.e., ex-soldiers, arms associations and whatnot. And why? Because you had to tell the story, and not only with photographs in newspapers or books, but photographs also as exhibitions, exhibitions that became debate. The extraordinariness of photography is that everyone through photography becomes aware of the place. Having said that, then, your photography can have so many paths. I always thought that these reportages could have a path of a book, so that the book becomes debate, the debate becomes discussion, the discussion expands, and thousands of people take note that there is this beyond the newspaper, beyond the usual photograph. I find today’s condition of Italian prisons shameful, and I find it shameful that no one is outraged. Prison should be a place where one enters to stop for a moment from despair and life, catch one’s breath, and then leave. That seems to me to be the easiest thing, while instead he often enters prison and the conditions are such that he gets out and you still go and commit crimes.

We come to the fifth section, Libertade. Here we are in an important part of his production, with the photographs of Guinea, Angola, Portugal with the Carnation Revolution.

’68 and these events led me to shoot in many parts of the world where facts and circumstances were happening that intrigued me, because the first characteristic of a freelance reporter is curiosity: trying to understand, going to try to understand what (although I still went to many places where I didn’t understand anything). Back then we were talking about the Third World: there was, of course, the Soviet Union and the Eastern countries, there was the America of capitalism, but there was also imperialism, and Europe was a series of imperialist nations. I was working with a newspaper in Paris called Jeune Afrique, which told the stories of the Third World, made by extraordinary journalists, very good ones, in French, and which had a couple of Italians on the editorial staff, including Bruno Crimi. That meant that we started to think about going to tell African stories, with continuous trips to a revolutionary Algeria, to the Maghreb countries, to other parts of Africa. And there I photographer would go and tell their story because nobody was talking about it. And so here are the trips not to photograph the war, but to tell how what was happening in a small nation where there was still a fascist regime, that is Portugal, a colonialist nation, which had vast possessions and had been exploiting for many decades, centuries, which were Angola, Mozambique, Guinea, Sao Tomé. And so I photographed for a long time and tried to tell the story of the birth of an African democracy within a war of liberation with the soldiers, with the partisans, with the people, with the collective camps, with the women, with the schooling. And when these photographs then arrived on the table of many newsrooms it was a surprise, but more importantly it was a contribution to their liberation struggle. Because when American newspapers started publishing these photographs, well, a lot of things changed, from looking at Portugal to solidarity. And then I made a book out of it that was very important for them because it was the first book that told about Guinea, told their story, a book that went to the United Nations. And when you see that photography, with a book by Bruno Crimi and Uliano Lucas, comes to a U.N. commission and this U.N. commission determines that three-quarters of Guinea is free, and it does it through a book, then you wonder why others are not suited to tell these things. It also applies to Angola, where an extraordinary woman, Augusta Conchiglia, also went and did a report, because in Italy there was a remarkable movement of solidarity with these countries and their leaders. I went to Portugal several times, clandestinely, to report on a country that was then 10 million people, poor, of emigrants, because there were no photographs of the real Portugal. I told about it at the moment when the captains took power in a coup d’état and freed Portugal from a vicious dictatorship, I told about the end of a war for freedom. And then the captains who handed power back to the people after a lifetime. After centuries. Right now for Portugal we are on the 50th anniversary, and my photographs that tell the story of all this are on display in some exhibitions: there was one at the Lisbon Museum, and now another big exhibition is going around Portuguese cities, and it will go to Brazil in May, and it will tour Brazil a little bit. So the photographs of a reportage by an Italian author, then happily unknown, have become the material that for the Portuguese is fundamental, because there is nothing else that tells their story. And this is also something that is intertwined with so many other stories, so this is the only documentation that there is also for these countries, which may have ended badly, but with the war of liberation they became free.

The sixth section of the exhibition is titled War or Peace.

I have been in various theaters of war but I am not a war photographer, I have been very careful about that, I photograph peace, not war. There are war photographers or there are photographers who go to a place and after a week come back, but the problem is that so many photographers of this type of photography go to certain places, even risking, but to sell photographs, because in the end big publishing wants, as usual, the photos with the children who are dying. And you photograph the children that is dying, then you don’t give a shit because you eventually have a plane ticket home but the children stay there, the old people stay there, and the stories of the wars around us are all made-up photography, constructed, but constructed because the market wants that, it wants the old people, the children, the escape, the carts that go. All the desperation, all to give a glimpse like on television, a construction. But war is blood: if you go into a house where a shell has come you find nothing, that is you find death, instead in war photography death is never there. Also because if you photographer take such pictures, today nobody publishes them to you. And so here is the fundamental experience like the long months I spent in Sarajevo and other parts of Yugoslavia, in what was a siege of a medieval city, three years of siege in our civilized or supposedly civilized Europe, where the narrative was to live the everyday life with the people of Sarajevo, and this everyday life allowed me to make counter photographs. People lived with great dignity. There was even in the cellars a kind of little theater where I met Susan Sontag, to give you an idea. There was an activity. Women and teachers went to school in the morning on starvation wages. They were photographs that no newspaper wanted. Because the mechanism was that everybody wanted blood. But you had to tell a siege of people who nevertheless lived, resisted and with great dignity. I did that and the reportage came out, with many stories. Unraveling all these stories through photography is very difficult, so most photographers, I repeat again, do what they can then sell, so what can sell at a certain time to international journalism? The crying child, the suffering child, the crying woman, the escape. But that is not the story. Therefore, even the figure of the photojournalist is now in disarmament, and that means he retires and closes down, because others with modern technologies can take photographs.

The last section of the exhibition is entitled The Human Condition 1968-2021.

It is a section that brings together several things. I started very young collaborating on a newspaper called Il mondo: it was a very important newspaper because it was a liberal-progressive weekly, run by very fine intellectuals, and it started using photography in an extraordinary way. Very widely read: that’s where they started signing up those who later became writers, painters and also other leading figures in the cultural scene of these last fifty years. I published my first photographs there. And they were photographs that I took on the street, and shooting on the street is extraordinary: you come and walk around a day on the street, downtown, the suburbs, wherever you want, and you try to tell what’s going on, kids running around, kids playing, people kissing under a statue, a sign, a priest who’s passing by-anything that can tell the story of the life of a provincial town. You have to be in there walking though, your eye has to observe and you have to show. Street photography taught me about love. Observe, look at love. This is the data. This love that surrounds us, not the frenzy or anything else. And then you in slow steps go in and make up a story, which can last a second or ten minutes, a quarter of an hour, however a photograph can last decades. To give you an idea, there is a reception center near Turin, run by Red Cross. I went, decided to make a long report, a place that collects and was collecting in 2019 a thousand political refugees, mostly people who had suffered persecution for their ideas or their condition. It was wonderfully run. The raped women had psychiatric, psychological and gynecological care, in short, a wonderful place. I wondered why this works and on the other side, instead we are always the baruff and there is something that does not work. With photography we told about this place and I made a book out of it with a big exhibition that was presented at the Cinema Museum in Turin. Inside this book is a photograph of a girl, she couldn’t have been more than 16 years old, who is looking at you while she is feeding her baby. This picture signifies peace after the ugliness of a war. But war is not combat: war is this girl who has been beaten, abused, raped. It is the war of those who cannot defend themselves, and then you give them back their lives, that necessary time, which can last even years, for them to recover and return within a society. This is peace. Peace is looking through photographs for these people without exhibitionism, without patheticism, without a sense of goodness -- normality. The future of the world, the future of the world is in dialogue. This is my vision. There is nothing else.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.