In November, the Uffizi will open a major exhibition dedicated to the great man of letters Pietro Aretino (Arezzo, 1492 - Venice, 1556), entitled Pietro Aretino and the Art of the Renaissance (Aula Magliabechiana of the Uffizi, from November 27, 2019 to March 1, 2020): the first exhibition entirely centered on the poet and writer, it will analyze the figure in his historical and cultural context, and especially in relation to his profound relationship with art and artists. The exhibition is curated by Anna Bisceglia, Matteo Ceriana and Paolo Procaccioli: our editor Federico Giannini interviewed Anna Bisceglia, Matteo Ceriana and Paolo Procaccioli to draw a double profile, historical-artistic and artistic-literary, of the great Aretino. Below are interviews with Anna Bisceglia, curator of sixteenth-century painting at the Uffizi Galleries, and Matteo Ceriana, director of the Palatina Gallery: with them we delved into Aretino’s relationship with, respectively, painting and sculpture, and with Anna Bisceglia we also talked about the reasons behind the exhibition. Below is the interview with Anna Bisceglia.

FG. How did the idea of dedicating an exhibition to Pietro Aretino come about?

AB. The idea of this exhibition was born five years ago in 2014 by Matteo Ceriana and myself, because the Palatina Gallery preserves the Portrait of Pietro Aretino executed by Titian in 1545. Then we were also moved by the fact that, starting at least in 2013 with the exhibition on Pietro Bembo, and then with the subsequent ones dedicated to Aldo Manuzio and Ludovico Ariosto, a field of interest had opened up that intertwined literature and art history, so the focus was on the artistic interests of the literati and the reconstruction of the contexts in which writers had also contributed to the formation of artistic language, either through their collections, or through their choices, or again through their friendships, and so on. And indeed, after very important personalities such as those just mentioned, who were also related to the arts, had been dealt with, Pietro Aretino remained somewhat in suspense: this was the motivation that led us to plan an exhibition on him. Of course, in this journey it was essential to meet with specialists who on several sides touched on the figure and work of Aretino; it is a work that could be done only in a choral way, consulting many and authoritative voices, and in this sense it was intended to promote a conference that took place at the Cini Foundation in the fall of 2018, which allowed us to cross thoughts, ideas, focus on the most important themes, and seek answers. The catalog will be a summary for the visitor, designed as a guide to the exhibition, but on the sidelines there will also be a volume of essays that will deal extensively with the topics covered in the exhibition for those who wish to explore further. What’s more, given that the exhibition falls in 2019, the year of the 500th anniversary of the birth of Cosimo I de’ Medici (a year that was not purposely chosen because we had initially thought we could do it in 2018, then the complexity of the subject matter brought us to 2019), we can say that it also manages to contribute, for its part, to the celebrations of the Cosimian year, because the relationship between Pietro and Cosimo is very intense, and by the way, the portrait we have in the Palatina is a gift sent precisely to Cosimo by Aretino himself, in 1545.

We said that Pietro Aretino, among many others, contributed to the construction of an artistic language. Wanting to go into it, what was his contribution?

Aretino is, meanwhile, one of the main witnesses to the artistic events taking place in Rome and Venice. However, his main contribution lies in his personal relationship with the artists he meets moving his life trajectory mainly between these two centers so important in the sixteenth century. However, his interest in the arts had already matured in his early youth spent in Perugia in the first decade of the century and continued during his stay in Mantua in the second half of the 1920s as he moved from Rome to Venice. He had relations with the leading artists of his time, with whom he maintained epistolary relations, to even bonds of friendship, when not of true affection. This intense web of exchanges is reconstructed through the six books of Letters, which represent the invention of a truly new literary genre, inaugurated by Aretino well in advance of Bembo. Pietro Aretino’s correspondence is an inexhaustible source of historical, political news; it traces the portrait of an era. From the artistic point of view , they constitute a truly interesting testimony: not by chance from a bibliographical point of view, the need had been felt in the 1950s to publish separately the letters addressed to artists (in particular I refer to Pietro Aretino’s Letters on Art edited by Fidenzio Pertile and Ettore Camesasca, 1957-1960). It is necessary that out of about three thousand two hundred letters sent to his correspondents, about seven hundred are sent directly to artists, or which speak of things of art: quite an impressive proportion. Aretino’s main relationships are above all with all the great artists of the day, starting with Titian and Sansovino with whom he structured what was called the triumvirate in Venice, a sort of potentate of the arts through which the three shook hands lun l’altro: for example, Aretino sponsored Titian, and Titian with his works celebrated Aretino: a real joint venture projected to build lascesa of both of them at the major European courts, mainly at the Emperor Charles V. Their strategy was fundamentally based on the production and sending of works: Aretino assumes the role of go-between and patron in sending paintings, medals, sculptures, to which he accompanies his long letters with descriptive ekphrasis and often even a sonnet (a practice, the latter, quite common for the literature of the time). What is striking about Aretino, however, is his verbal laderenza (to use Longinian terminology): his goal is to represent painting through his words, with ink that becomes color. No one more than he has been able to illustrate the novelty of Titian’s painting, highlighting the painter’s particular ability to make his images seem “alive and true.” Explaining his portrait in a letter to Cosimo I in 1545, Aretino writes: it breathes, beats the wrists and mòve the spirit, in the way that I do in la viva. Or, when describing, in a letter to Titian in 1547, theEcce Homo he had received as a gift from him (a copy of one executed for the Emperor, and now in the Prado) he says of it: Of thorns is the crown that pierces him, and blood is the blood that their points cause him to shed; nor otherwise can the scourge enfold and bruise the flesh, than if your divine brush had made it livid and enfeebled; the sorrow, in which the figure of Jesus is shrunk, moves to repentance whosoever Christianly beholds his arms severed by the rope, which binds his hands; he learns to be humble who contemplates the miserable act of the reed which he holds in his right hand; nor dares to hold in himself point of hatred and rancor he who beholds the peaceful grace which in the semblance shows. These are words that flagrantly explain the secret of Titian’s art, those qualities that had brought him success on the Venetian scene as early as the 1930s, when he won the confrontation with Pordenone following the competition for the execution of the large canvas with the Martyrdom of St. Peter of Verona for the Dominican church of Saints John and Paul. Aretino by the way had greatly appreciated Pordenone for his Roman sojourn and his rapprochement with Michelangelo, but Titian decisively wins that confrontation, and Peter testifies to it firsthand. And here we come to a nodal premise in Aretine’s conception of artistic developments: the recognition of the primacy of the modern manner that had developed in Rome between the second and third decades of the century, to which Aretino, who had grown up in the Rome of Leo X of Agostino Chigi and Clement VII, had been a direct witness. It was a bond that would never be severed: still in the 1940s, from Venice, he would ask for news of artists from Raphael’s school, such as Perin del Vaga, for example. His arrival in Venice coincides, moreover, with the diaspora of artists coming from Rome after the Sacco, Sansovino in primis, but also Rosso, and this contributes to a set of connections of which he does not struggle to become a speaking and written voice. In essence it is within these two poles that his vision of artistic unfolding is resolved: the modern Roman manner transmigrated to Venice.

|

| Johann Carl Loth, Martyrdom of St. Peter Verona, copy from Titian’s original destroyed by fire in 1867 (1691; oil on canvas; Venice, Santi Giovanni e Paolo). Ph. Credit Didier Descouens |

Earlier we mentioned Titian’s portrait, which is the most vivid testimony to the relationship between Pietro Aretino and the arts in Florence. In this sense, I would like to build a small path on the relationship between Aretino and the arts through three works, starting precisely from the portrait of Titian: what can we say about this work? What does it tell about Aretino, about his relationship with Titian?

It is a very interesting portrait because it should be read on different levels: on the one hand because of the function of the portrait, which in the sixteenth century is fundamental, much more than before, because it is the attestation of the function and the social role of the effigy, and then it is also used, not only by Aretino, as a bargaining chip. Aretino takes full advantage of the full range of possibilities offered by the portrait; among other things in a letter to Sansovino he defends the necessity of portraying personages of rank, in order to eternalize their value: not everyone is worthy of having a portrait. This is a most singular affirmation, given that Aretino, and this is really surprising in his life parable, was of very modest origins: the earliest biographers believed him to have been born of an illegitimate relationship of his mother, Tita, with a member of the Bacci family; documents and direct testimonies say he was the son of a shoemaker. His is therefore a formidable rise in the Italian society of the time, truly transversal, if only to compare it with today’s society. This condition of his does not allow him a canonical education, such as Pietro Bembo or Baldassarre Castiglione might have had, for instance: he is not born with a collection a family library behind him. This aspect, too, helps us to understand his focus essentially on art contemporary to him. And after all, the use of the artistic product is also a strategic use: the portrait also becomes for him an instrument of self-promotion. From the mid-1920s until his death, all his moves have as their basis the affirmation and consolidation of his image as secretary of the world (as he calls himself in one of his missives), as a point of reference on the national and international scene. The network of relationships and friendships he built was also functional for practical reasons, that is, for his livelihood: as a man of letters, a lover of the good life and luxury, he practically lived off the commissions he obtained from the world’s powerful, the Emperor, the King of France, the Duke of Urbino and so on. In the exhibition we intend to give an account of this aspect through a roundup of his portraits, executed at different times: from the first, engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi in the mid-1920s, at the time of his intense frequentation of the Roman curia. Juxtaposed to this is a painting, from the same years, made by Sebastiano del Piombo and donated by Aretino to the City of Arezzo, where it still stands today, placed in the council chamber. It was a symbolic gesture, aimed at presenting himself with the dignity of an illustrious personage to his fellow citizens, and Aretino appears there with elements such as the scroll, the laurel branch and the masks that decisively qualify him as a man of letters. In the following decades Aretino entrusted his likeness to medals, and we will display some by Leone Leoni, Alessandro Vittoria, and Girolamo Lombardo, which document his face over the years through the limponence of an allantica profile. The medal, after all, was also used by him as a gift and thus lent itself well to spreading his image. Returning to Titian’s portrait, one of the two known to date (the other is in the Frick Collection in New York and unfortunately will not be able to be displayed in the exhibition because, as we know, the original part of the collection is immovable), it must be said that it is indeed a telling portrait of Aretino’s social affirmation, of his role on the Venetian scene. A role that, it should be pointed out, was never decision-making, as he never held any public office. But Aretino was rather what today we would call an influencer, and he makes this clear to us in each of his lines, at least until the late 1940s. Titian interprets this demand perfectly: the protagonist wears a very rich satin robe (he was continually receiving fine clothes and fabrics as gifts), sports a heavy gold chain around his neck, again one of the many he received as gifts, the most famous of all being given to him by Francis I, King of France, a gold necklace with tongues of enamel, a quite significant allusion to the vivacity and power of his pen. It is, in short, a representation of status. However, this painting is also, at the same time, an extraordinary painterly evidence of Titian’s style in the mid-1940s, a wavy, flaky painting, with rapid brush strokes defining the surfaces, the chromatic contrast between the red of the robe and the fleshy flesh, and the terrible, vivid gaze. Certainly a culture far removed from the crystalline, wonderfully analytical manner marked by Bronzino’s primacy of drawing that dominated in Florence. In sending the painting to the Grand Duke, Aretino plays a bit of a counterpoint, and points out that Titian should have finished it better, but this is in my opinion a rhetorical device: Aretino absolutely believed in Titian’s worth and in the importance of this portrait, in which he also had high hopes since he aspired to receive Cosimo’s support.

|

| Titian, Portrait of Pietro Aretino (1545; oil on canvas; Florence, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

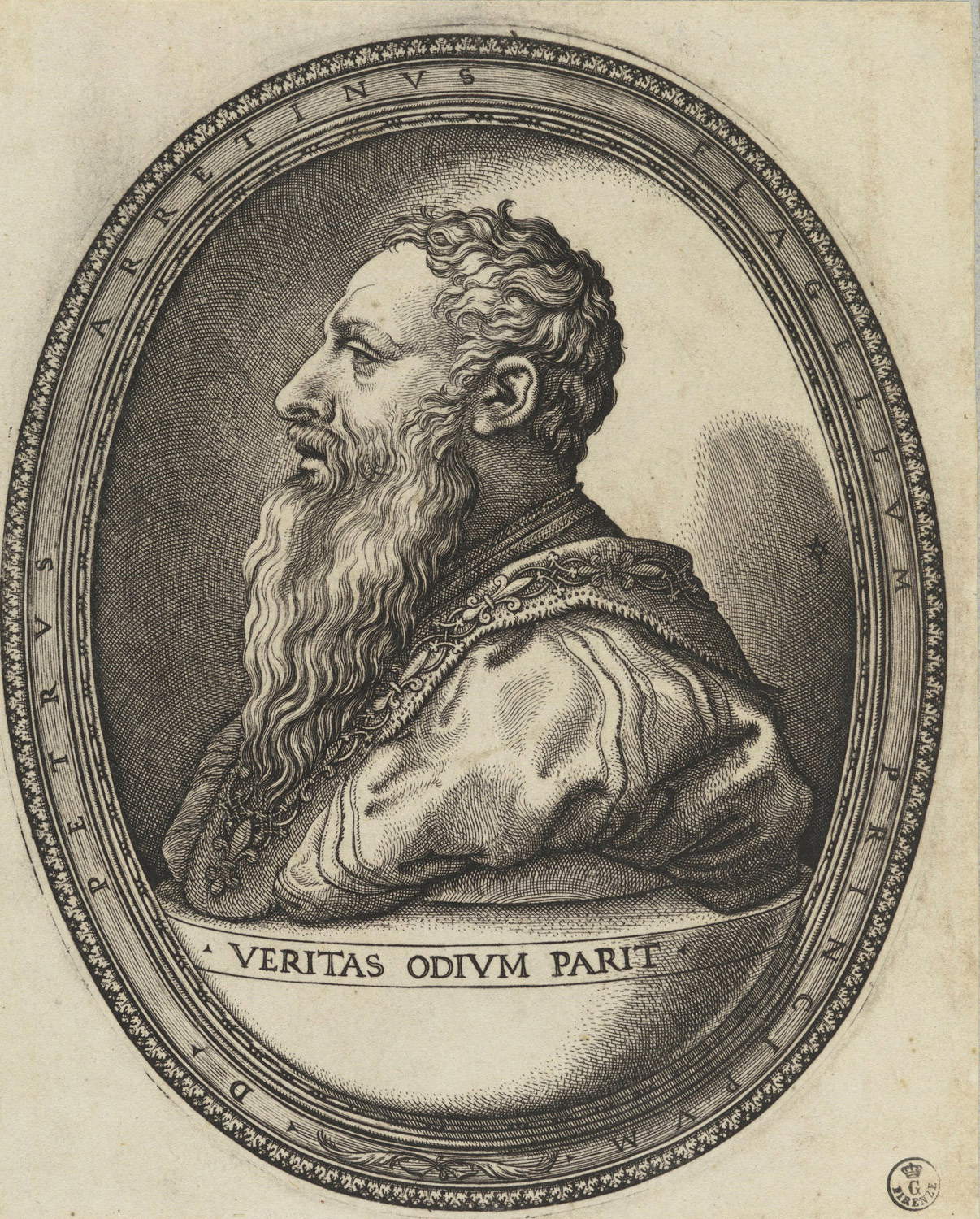

And again on the subject of portraits, we talked about those in which he had himself portrayed in profile, and in the exhibition there will be one of this type, posthumously engraved by Giovanni Giacomo Caraglio: it is a very interesting work because we find a couple of elements that catch the eye, one being the famous epithet “Scourge of princes,” and the other being a part of Terence’s famous phrase that says “Veritas odium parit,” “truth attracts hatred.” What message was intended to be sent?

Scourge of Princes is a fulminating definition voiced by Ludovico Ariosto in the final canto of the Furioso, where Aretino appears in the crowd of literati, poets and famous women who welcome the poet at the end of his imaginary journey of knights and heroes. Together with the Terenzian motto, it is one of those phrases that combine to compose a kind of allegory, a world that connects to Aretino’s emergence by defining what is his ... defense. We know that Aretino, from the time when on the Roman scene, most closely linked to the Medici popes, he hunted in pasquinades (from burlesque poetry to invective), is made the object of a series of attacks that first of all begin with Pope Clement VII’s date, Gian Matteo Giberti, who is even considered to be the instigator of the attempted assassination of Aretino: the man of letters is ambushed from which he fortunately escapes. Following this episode he would leave Rome for good. And from that moment, of course, he has a whole political side against him: in fact, it should be stressed that all of Aretino’s affairs should not be framed in the perspective of personal clashes or personal enmities; everything should, if anything, be seen within the very complicated framework of political relations in Italy at that time. When Rome was located, the great political clash was over the issue of whether the pope should support the French or the imperialists: the choice to support the French would later lead to the tragedy of the Sack of Rome, with the descent of the Lansquenets and the city put to the sword. Wrong choices in the pope’s policy determined a whole framework of relationships from which then descended what is one of the resounding facts in the history of sixteenth-century Italy, precisely the Sack of Rome. Having said that, Aretino, throughout his life, had to defend himself from attacks of a political and literary nature that were naturally in response to his invectives and at the same time also in response to a whole strand that was the one opposed to him and that tended to put him in a bad light and to limit his power (of influence and of speech) that instead in the central decades of the sixteenth century had become really remarkable: one only has to skim through the first two books of letters to get an idea of what the arc of his correspondents was (there is, for example, the whole court of Charles V: the emperor himself in 1530 had wanted to meet him and ride with him, and this is an image he will always remember). There are, among others, the very powerful Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, there is the Spanish ambassador to Venice, Diego Hurtaldo de Mendoza, who was also a bibliophile and an art connoisseur, there are the French because he manages to have good relations with the king of France, there is the king of England, there are the Fugger bankers with whom he sponsored Titian. If we were to draw on a map the whole geographical arc to which Aretino’s letters reach, we would have a vast area. And this really makes him a European man, from a certain point of view: his ability to hold diplomatic relations, to know how to also finely interpret historical situations, to always keep an eye on what was the situation of art by suggesting this or that artist, is impressive. Aretino is also the person who launches Leone Leoni, at that time a young artist whose abilities he immediately understands, recommending him to the imperial environment: in the exhibition we will host a spectacular bronze relief of him with the profile of Charles V, generously granted by the Louvre, a loan for which we are particularly grateful. So with Aretino we are really witnessing the promotion of an artist from his birth. With Titian it had been different because he had already established himself on his own and knew Aretino when he was already in vogue, however Leone Leoni and other artists from Sansovino’s circle, are really “recommended” and presented on the scene by Aretino. And then let us not forget that Vasari himself arrived in Venice in 1541 and from Aretino received one of the commissions that officially introduced him: the design for the apparatus of the comedy la Talanta that Aretino had composed and dedicated to Cosimo I and which was staged in 1542.

|

| Giovanni Giacomo Caraglio, Portrait of Pietro Aretino with Motto (1646-1655; burin, Florence, Uffizi, Cabinet of Drawings and Prints) |

The last work I would like to talk about is the female portrait, the so-called Fornarina, by Sebastiano del Piombo kept in the Uffizi...

Meanwhile, it is necessary to specify that the exhibition follows a double criterion, chronological and iconographic, so there are four chronological sections that follow Aretino’s life from his beginnings in Arezzo and Perugia (that is, his birth and his first apprenticeship in the literary milieu), continuing through Rome (where he begins his early maturation), to Mantua and Venice. Next to these chronological sections there are then two sections that are iconographic and documentary, which are entitled “Secretary of the World” and “Imago Petri,” respectively, and which represent, in the first case, his framework of relationships (“Secretary of the World” is an expression Aretino himself uses in one of his letters when, boasting of his entire span of knowledge, he claims to be the “secretary of the world,” meaning that he manages to have in-depth relations and relationships with the entire world that matters), and in the second case, Aretino’s iconography that is attested in a depiction of the self that is also an instrument of promotion. The Fornarina, in all of this, falls within the Roman period: the Uffizi Galleries are fortunate because, thanks to collecting connections in which the Medici always played a very prominent role, they possess this work that belonged to Agostino Chigi, dating from the period in which Pietro Aretino arrived in Rome (its first certain attestation is 1517 but it is likely that he arrived in the city even earlier). Arriving in Rome in 1517 meant seeing Raphael and his workshop in action, seeing the frescoes in the Farnesina, the Vatican Loggias and the tapestries for the Sistine in progress, or the design for the Hall of Constantine, so it meant seeing the birth of the modern manner. At that time, Agostino Chigi was having the decoration of his villa completed, the Sodom frescoes had just been discovered, and Sebastiano del Piombo was one of his leading artists. In Agostino Chigi’s collection was, indeed, the Fornarina, which recalls not only the art chapters of that moment but also a very strong friendship with Sebastiano that was consummated in the Rome of that time and that Sebastiano would later prefer to cut off after he took on the official role of papal lead. The two will break off relations about the end of the 1930s, but in the Roman years they were very close, so the Fornarina, like every work in the exhibition, plays on this double track: the relationship with Aretino and the representation of the work within its context, within the context of the artist who had relations with him. In this case there is also an important patronage: Agostino Chigi is in fact the first one who introduces Aretino inside the beautiful, luxurious, very refined world, so it is his first connection with the Roman environment and the luniverso of its arts: it is there that Pietro Aretino begins to know the major protagonists of the modern manner many of whom artists will continue to mark his existence. Raphael plays a very important role because, even after leaving Rome, Aretino will continue to remember his magisterium not surprisingly also celebrated in the Dialogue on Painting or Ludovico Dolce’s Aretino who precisely of Aretino had been one of his secretaries.

|

| Sebastiano del Piombo, Female Portrait known as the Fornarina (1512; oil on canvas; Florence, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

Pietro Aretino today is mostly remembered for the more licentious part of his production, and for this reason there is a tendency to associate him with that “Boccaccio-esque” image spread first of all by the morbid interest in his work that became widespread in the nineteenth century, and then by the whole B-filmography of the 1970s that focused on these aspects in a grotesque way. How to restore to Aretino his stature as an intellectual and also the modernity of his thought and work?

The exhibition intends to do just that, since the figure of Aretino has always been burdened by prejudice, and his figure was put on the index immediately, as early as 1559. Prejudice then ended up crushing Aretino on the stereotype of the licentious writer and of the man with a malevolent, irascible character, and who basically made a living on backbiting. In reality this is not the case, and proving it is indeed the purpose of the exhibition, not least because from the point of view of scholarship the recovery of Aretino is quite recent. How to demonstrate this? It is immediately understood from the intention of the title: the exhibition is exactly the representation of Aretino’s relationship with the arts and with the patrons of the arts during the span of a thirty-five-year period, that is, the first half of the sixteenth century, following that direct testimony that are his letters. Our ambition would be to explain through the sequence of the works and the dialogue of the works (and of course the didactic apparatuses) how much Aretino represents a real world that opens up far beyond the idea of the licentious writer or the malevolent gossip. And this should emerge precisely from the exhibition of the works.

To conclude: from the art-historical point of view, what will be the main highlights of the exhibition?

We want to show that Aretino, even before Vasari, consciously traces the main lines of sixteenth-century Italian art and does so in a militant way. Roberto Longhi not by chance called him the patriarch of Italian connoisseurs. Specifically, then, we can anticipate that there will be some documentary novelties regarding the biography that will be made known in the catalog, and in general we have tried to draw a path of little-seen works: there is, for example, a very fascinating portrait of Aretino that comes from Basel (it is one of his most interesting early portraits) and for which a new attribution will likely be proposed, since the attribution of this painting has always been a doubt (it was thought to be by Sebastiano del Piombo or Moretto). There are drawings of erotic scenes by Giovanni da Udine, linked to the fortunes of the Lustful Sonnets, which have never been too widely seen and which serve to explain the fortune of that genre in the decoration of the time: indeed, it should be pointed out that Aretino composed the Sonnets over licentious images, those of Giulio Romano, later engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, reflecting a current of taste inaugurated by the school of Raphael. Giovanni da Udine’s drawings are therefore very interesting because they present a particular interpretation of mythological erotica. Among other things, this theme connects somewhat with the exhibition in Mantua on Giulio Romano where, precisely, these aspects will also be examined. And then we will see works that are quite well known but little shown in exhibitions, for example, the portrait of Cardinal Granvelle that will come from Kansas City and that has never been exhibited in Italy: it is an absolutely stunning 1545 portrait by Titian that thanks to the generosity of the Nelson-Atkins Museum we are lucky enough to be able to include in the itinerary. To summarize, there will be unpublished works of a documentary nature as well as works that are rarely seen: it was not our intention to do a blockbuster exhibition, nor to do an exhibition on the Renaissance in Venice, also because there are not all the Venetian artists, but a selection of the most important ones, trying to highlight the focal and crucial points of Aretino’s relationship with the arts and relaunching this writer who, in the end, was also taken as an easy vessel for a creation of a type of cinematography with which he, moreover, had nothing to do. Partially relaunching him was masterfully done by Ermanno Olmi, if we consider that the first five minutes of Il mestiere delle armi are occupied by a long sequence of characters who bring to life Aretino’s letter to Francesco degli Albizzi about the death of Giovanni dalle Bande Nere: and in the first frame it is Aretino himself who gives the lincipit, turning to the viewer, with a penetrating and solemn gaze. And in our opinion this is ... good compensation.

|

| Titian, Portrait of Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle (1548; oil on canvas, 113 x 87 cm; Kansas, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) |

Following is an interview with Matteo Ceriana.

FG. We said that Pietro Aretino formed a sort of “triumvirate” with Titian and Sansovino. With Anna Bisceglia we delved into the relationship that bound him with Titian. In what terms, however, was the link with Sansovino established?

MC. The relationship with Sansovino is very close, almost familial. Aretino has known Jacopo since his time in Rome, they have common experiences in those extraordinary and crucial second-third decades, they knew the same people, the same artists, the same situations. Plus they both speak a Tuscan vernacular in a context that speaks Venetian. Aretino also knows and follows Francesco Sansovino the son of Jacopo who by the way will eventually do the same job as him, entirely new and modern, that of the publicist writer. Aretino is well acquainted with Sansovino’s work, hangs out with him, visits his workshop and sees his drawings for architecture, his creative workshop. Aretino’s own architectural culture comes from frequenting Sansovino. Conversely, for Sansovino, Aretino’s works are important, especially the sacred works, as an example of narration of the sacred fact with an entirely new icastic force.

More generally, what was Pietro Aretino’s relationship with sculpture and what works in the exhibition give us an account of it?

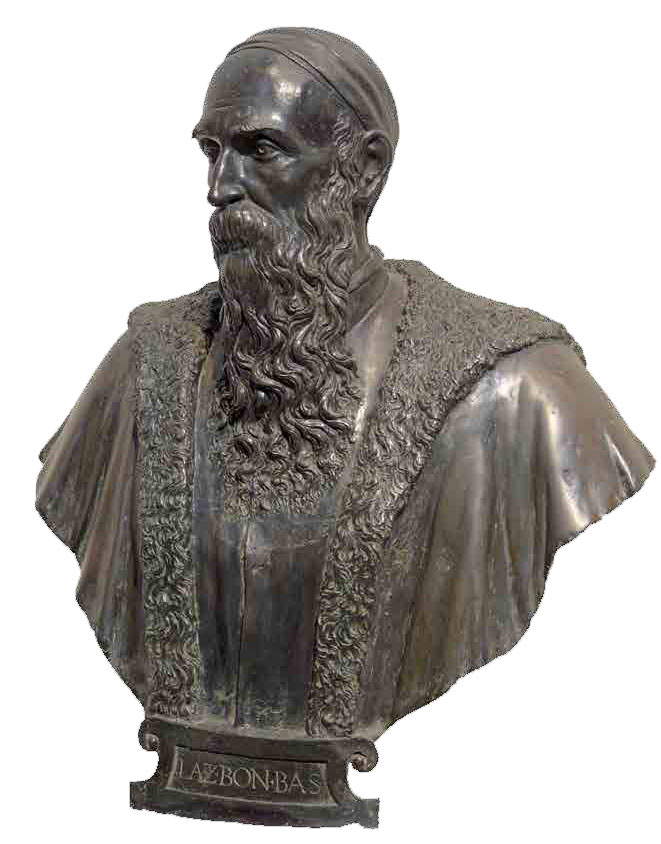

Aretino corresponded with and knew many sculptors from Sansovino’s stable. With some, like Danese Cattaneo he has a close relationship because Danese, besides being Tuscan, is also a writer. Moreover, Aretino is also interested in the minor arts (wood carvers, gem engravers) and medals, which in the sixteenth century were a main instrument of self-promotion. For its part, Aretino’s ecphrastic word aims at a plastic density. Aretino is also said to sculpt with words. In his work, in the sumptuous prose of sacred works, plastic metaphors and descriptions of sculptures. On display are works by Sansovino, both original models and finished works. Then, for Jacopo’s workshop, there is the bust of Lazzaro Bonamico sculpted by Danese Cattaneo for his tomb (of which Aretino speaks) and a Paduan sketch by Ammannati for another acquaintance of Aretino, Marco Mantova Benavides. The medals will be given ample space precisely because of their importance in the period and will serve to display the figures in relation to Aretino.

Finally, a question about the exhibition: how is the scanning of the sections that will compose it articulated?

It is partly chronological and partly thematic scanning. It is obvious to follow Peter’s life in successive sections from Perugia, Rome, Mantua to Venice, but then it is important to give an account of the various sides of Aretino’s work, his relationship with the powerful and those who confronted Aretino, used him and were used, his way of self-presenting himself to the world (the portraits and medals). The last short section is that of Peter’s posthumous fortunes, from the indexing of his entire oeuvre shortly after his death to the cursed myth in the nineteenth century.

|

| Danese Cattaneo, Bust of Lazzaro Bonamico (bronze, 76 x 86 x 32 cm; Bassano, Museo Civico) |

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.