A new museum in Florence: in fact, from January 2, in sumptuous new spaces that have just been set up, the Museum of Russian Icons opens in the Pitti Palace, where 78 ancient icons can be admired. These are works from the Medici and especially the Lorraine collections, and constitute the oldest collection of this kind outside Russia. The icons will be on display for the first time in a new setting: these are four large rooms with 17th-century frescoes, overlooking the courtyard on the ground floor of the Pitti Palace: newly restored, these spaces now become part of the palace’s normal tour itinerary. The museum’s layout (designed by Mauro Linari together with Paola Scortichini and Pietro Petullà, with lighting design by Linari himself and Claudia Gerola, and with art-historical curatorship by Daniela Parenti) is marked by lightness and transparency and privileges the ease of reading the icons, (equipped with descriptive captions in Italian, English and Cyrillic), while leaving intact the view of the 17th-century frescoes that adorn the walls and ceilings. This will be a novelty within the novelty: before now, in fact, these specially restored rooms of the Medici Palace have never before been regularly opened to the public. Even the striking, very elegant Palatine Chapel, with its 19th-century frescoes by Luigi Ademollo, now fully restored will be reopened and can be visited daily.

In addition, on the Uffizi Galleries website(www.uffizi.it/mostre-virtuali), the virtual exhibition curated by Daniela Parenti, curator of Medieval and 15th-century painting and Russian Icons at the Uffizi, entitled The Light of the Sacred: Russian Icons at the Pitti Palace, entirely dedicated to the treasures of this new museum, can be visited. Again, on the occasion of the opening of the Museum of Russian Icons, the first Russian-language video (with subtitles) is also published on the Uffizi website(www.uffizi.it/video-storie). It is an introduction to the historic collection at the Pitti Palace by Zelfira Tregulova, director of the Tret’yakovskaya Gallery in Moscow, the museum with the largest and most important collection of Russian icons in the world.

The Museum of Russian Icons at the

The Museum of Russian Icons at the The Museum of Russian Icons at the

The Museum of Russian Icons at the The

The

The Russian icons in the Uffizi Galleries were all executed between the late sixteenth and mid-eighteenth centuries. The oldest specimens belonged to the grand dukes of the Medici lineage and are already mentioned around the mid-17th century in the inventories of the furnishings of the Chapel of Relics in the Pitti Palace. By contrast, the largest group arrived in Florence during the reign of Francis Stephen of Lorraine (1737-1765).

Taken together, this collection of Russian icons, documented at the Pitti Palace in 1761, is the oldest preserved outside the territories of ancient Rus’, an entity roughly coinciding with the territories of western Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The oldest specimens in the collection, executed between the 16th and 17th centuries, can be traced back to painters who worked for the court of the tsars in the Kremlin Armory Palace in Moscow, the main center for art and production of this type of work before the founding of the new capital St. Petersburg. Many of the icons from the first decades of the eighteenth century are also inspired by models from the Moscow school, but they were likely made in provincial workshops in central Russia. These are mostly medium and small icons, intended for domestic and personal devotion. There are also some whose execution is probably due to masters active in Kostroma and Jaroslavl, ancient cities on the Volga River north of Moscow. For a few years in the late 18th century, the entire collection was displayed in the Uffizi Gallery as evidence of Byzantine painting as part of the rediscovery of Christian antiquities. In 1796, however, many specimens were removed from the exhibition and relegated largely to the Medici villa at Castello, where they remained until the early 20th century. In more recent years, several attempts were made to reinsert the collection into the city’s museum itineraries, first at the Pitti Palace, then at the Galleria dell’Accademia, but they had never been successful.

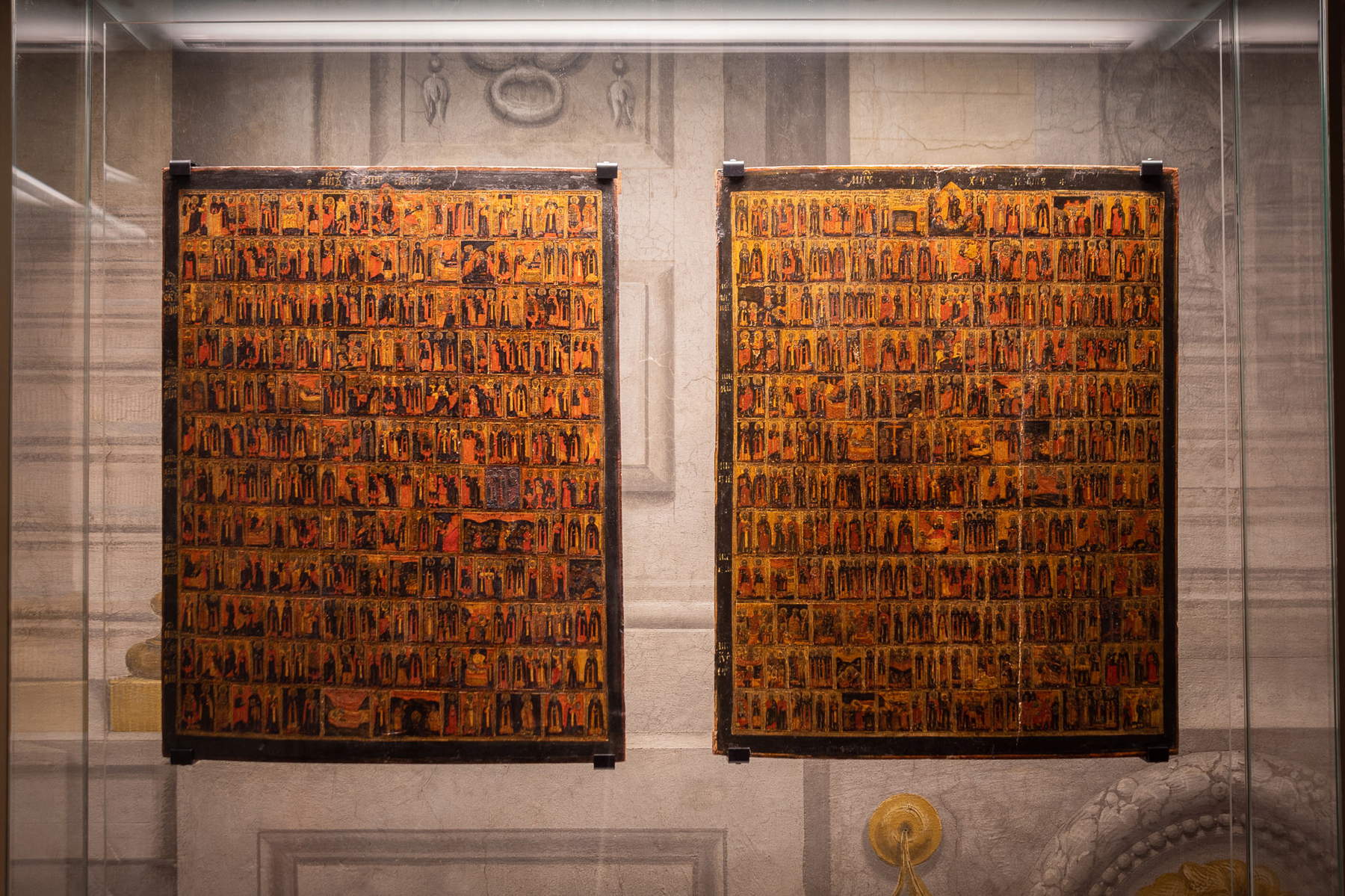

Among the most valuable works in the collection are the two panels that make up the Menologio, or calendar of Orthodox religious holidays divided by semesters: each panel consists of twenty horizontal rows with sacred scenes and figures of saints, each identified by an inscription. The icon with St. Catherine of Alexandria, can be dated to 1693-1694 thanks to the punch in the silver-gilt oklad (the metal coating that covers some parts of the icons). The martyr princess is depicted with attributes very similar to those depicted in Western art: the palm and wheel of martyrdom, books and armillary sphere that allude to her vast knowledge. The work is attributed to theatelier of the Palace Armory, the workshop that worked at the tsar’s court in the Kremlin Palace in Moscow, and is akin to the style of Kiril Ulanov, one of the best-known masters between the 17th and 18th centuries. Only one specimen in the Florentine collection is known to be the author, Vasily Grjaznov, who signed the icon of the Mother of God of Tichvin, dated July 16, 1728. It is a replica of the miraculous image that according to tradition appeared in 1383 in Tichvin, Novgorod territory. In the painting, the date is inscribed according to the Western system, which was introduced in Russia by Tsar Peter the Great (1672-1725) along with Arabic numerals and the Julian calendar, replacing the Byzantine calendar in use until then. The oldest specimens in the collection are the icon depicting the Mother of God, of the type called “In you let every creature rejoice,” and the one with the Beheading of the Baptist. Their arrival in Florence is linked to the collecting of the Medici. The two icons were in fact part of the liturgical objects kept in the Chapel of Relics in the Pitti Palace as early as 1639, at the time of the reign of Ferdinand II de’ Medici and his consort Vittoria della Rovere.

“With the opening of the Museum of Russian Icons, which coincides with the daily and permanent accessibility of the Palatine Chapel, now returned to its splendor thanks to expert lighting,” says Eike D. Schmidt, director of the Uffizi, “a great step is taken toward opening to the public all the frescoed rooms on the ground floor of the Pitti Palace: marvelous rooms, once inhabited by the grand dukes, unfortunately still largely used as offices and service rooms. The Florentine icon collection differs from the others in that it consists mainly of small and medium-sized specimens, intended for the private devotion of families and to be taken on journeys. The proximity of the Russian icons to the Palatine Chapel becomes a metaphor for a confessional bridge between Orthodox and Catholics that recalls the common spiritual roots and frequent cultural exchanges between Italy and Russia that have taken place over the centuries and still persist.”

“Russian icons,” says Sergey Razov, ambassador of the Russian Federation to Italy, “represent a fundamental heritage of Russian culture, encapsulating in them the spiritual experience of the Russian People and the Orthodox Church. Thanks to the collecting of the Grand Dukes of Florence, today for its inhabitants, as well as for guests of the city from all over the world, there is a unique opportunity to get in touch with the brilliant examples of Russian iconographic art and to obtain the keys to the spiritual and ethical roots of the whole Russian culture. I am convinced that this permanent exhibition will become an event of great value for our intensive dialogue in the field of culture and will incite all admirers of Russian art to travel to our country and visit Orthodox churches, temples and monasteries where the magnificent examples of Orthodox figurative art are kept. I wish the Uffizi Gallery new interesting projects and prosperity, instead its guests wonderful discoveries in the world of Russian iconography.”

“The association between the city of Florence and Russia is ancient, a strong bond through history,” emphasizes Eugenio Giani, president of the Region of Tuscany. “For example, on the ruins of the Medici residence of Pratolino the Demidoffs had their magnificent villa built. The Uffizi’s extremely important collection of icons is a testimony to this bond, and to be able to have it admired in its splendor and completeness by tourists from all over the world can only be a point of pride and confirmation of unmistakable signs of a fruitful and profound relationship that has bound them and binds them to our history.”

“The exhibition of the collection of Russian icons,” explains Daniela Parenti, curator of Russian Icons at the Uffizi Galleries, “responds to today’s need to broaden the cultural offer for an increasingly heterogeneous public eager to explore lesser-known contexts. At the same time, the return of Russian icons to Palazzo Pitti marks a further step forward in understanding the breadth of Grand Ducal collecting interests, both in the Medici and Lorraine eras.”

| Florence, new Museum of Russian Icons opens at Pitti Palace |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.