There is not only Lisippo’sAthlete, which Cultural Heritage Minister Alberto Bonisoli would like to return to Italy as soon as possible, or Jan van Huysum’s Flower Vase, which was stolen in Florence by the Nazis during World War II and which Uffizi Director Eike D. Schmidt, requested from Germany by launching an appeal for its return. There are a number of works that have left the national borders in various eras and that Italy would like to return: in some cases cultural diplomacy has already been at work for some time and it is not ruled out that the works may return, in other cases they are much less likely to be returned (almost “dreambook”), but they are always works that were part of Italian collections and that for various reasons ended up abroad (theft, war booty, illegal excavations... ). Without wanting to get into complicated questions of law, nor wanting to determine whether or not Italy might be right in the various disputes, we list below fifteen important works that have left Italy and for which there has been discussion about their possible return. As mentioned, in some cases these are remote eventualities, in others concrete possibilities: the list we propose is designed solely to give a dimension of the phenomenon.

1. Etruscan art, Chariot of Monteleone

(second quarter of 6th century BC; bronze and ivory, 130.9 x 209 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum)

The Etruscan Chariot of Monteleone is a precious object identified as a parade chariot that belonged to a high Etruscan dignitary: it is a very rare artifact, which features a rich decorative apparatus (with panels adorned with mythological subjects), strongly influenced by Greek art. The Chariot was found in 1902 in Monteleone di Spoleto by a local farmer: the finder sold it, after a series of negotiations involving other intermediaries, to the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Recent studies have discovered that it was an illicit sale: Italy has already forwarded a request to the United States for its restitution, and it is not certain that in the future the Monteleone Chariot may not be exhibited in one of our museums.

|

| Etruscan art, Chariot of Monteleone (second quarter of the 6th century BC; bronze and ivory, 130.9 x 209 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

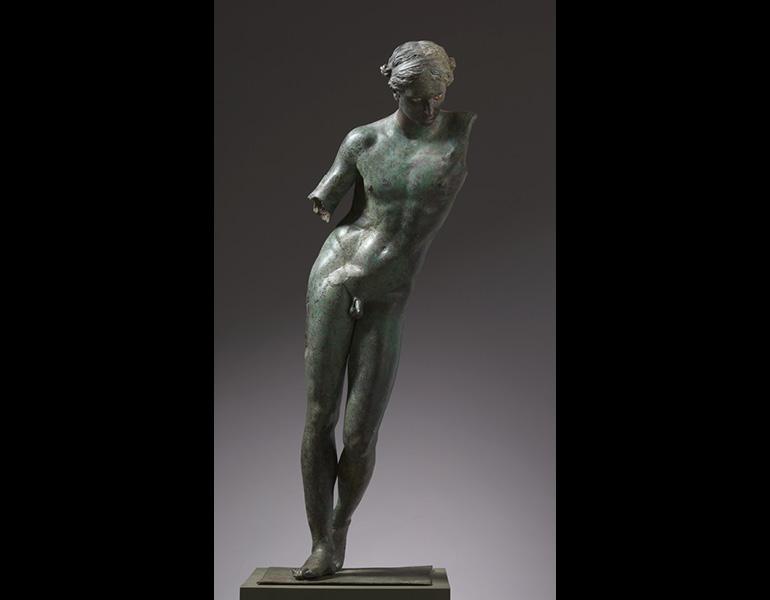

2. Praxiteles (attributed), Apollo Sauroktonos

(c. 350 BC; bronze, copper and stone, 150 x 50.3 x 66.8 cm; Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art)

This is a splendid and sensual Greek bronze statue attributed to one of the greatest sculptors of his time, Praxiteles: Apollo, god of the arts, is depicted in the iconography of Sauroktonos, or the slayer of the lizard (in fact, we see him in a pose that lets us imagine him about to pounce on the animal, which is not present in the depiction or, more likely, lost). The work is located in Cleveland and is the only known bronze version of the Apollo Sauroktonos: as to its provenance, the official version of the museum wants the statue to have been part of a private German collection and, according to the U.S. institute, to have come into the museum’s possession through some transfer of ownership. However, there are speculations that claim the work was found in the sea of Sicily, in the stretch between Mazara del Vallo and Pantelleria, where other Greek works have been found, and that it arrived in the United States through illicit routes.

|

| Praxiteles (attributed), Apollo Sauroktonos (c. 350 BC; bronze, copper, and stone, 150 x 50.3 x 66.8 cm; Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art) |

3. Giotto (attributed), Madonna and Child

(1297?; tempera on panel; private collection)

This Madonna and Child, attributed by some scholars to Giotto and by others to his school, was purchased at an auction in Florence in 1990 by an English collector, who bought it as a 19th-century panel (at the time it was thought to be a copy: the change in dating and attribution is a few years later). In 2007, however, the work was allegedly brought to England without the permission of the Italian authorities (this, at least, is the state’s claim). For the owner, however, the transfer would have been legal. Thus began a long legal battle with the goal of bringing the work back to Italy (it is currently still on English soil).

|

| Giotto (attributed), Madonna and Child (1297?; tempera on panel; private collection) |

4. Maestro dell’Osservanza, Flagellation

(1441; tempera and gold on panel, 45 x 30.5 cm; private collection)

Maestro dell’Osservanza’s Flagellation is a very rare biccherna, or panel painting that served as the cover of the annual state budget documents of the Republic of Siena (it was customary for the Republic to commission them from important artists): of the 136 known biccherna paintings, 105 are now in the Siena State Archives. The one by the Maestro dell’Osservanza went to auction at Sotheby’s in 2016 and fetched �?�1.632 million (against an estimate of between �?�470 and �?�700,000): however, according to the Italian state, the sale could not take place because the biccherna was a state property, the right of ownership of which belongs to the state. According to Sotheby’s, on the other hand, the sale was legitimate because the biccherna had been in a private German collection for decades. The situation is currently at a stalemate.

|

| Maestro dell’Osservanza, Flagellation (1441; tempera and gold on panel, 45 x 30.5 cm; Private collection) |

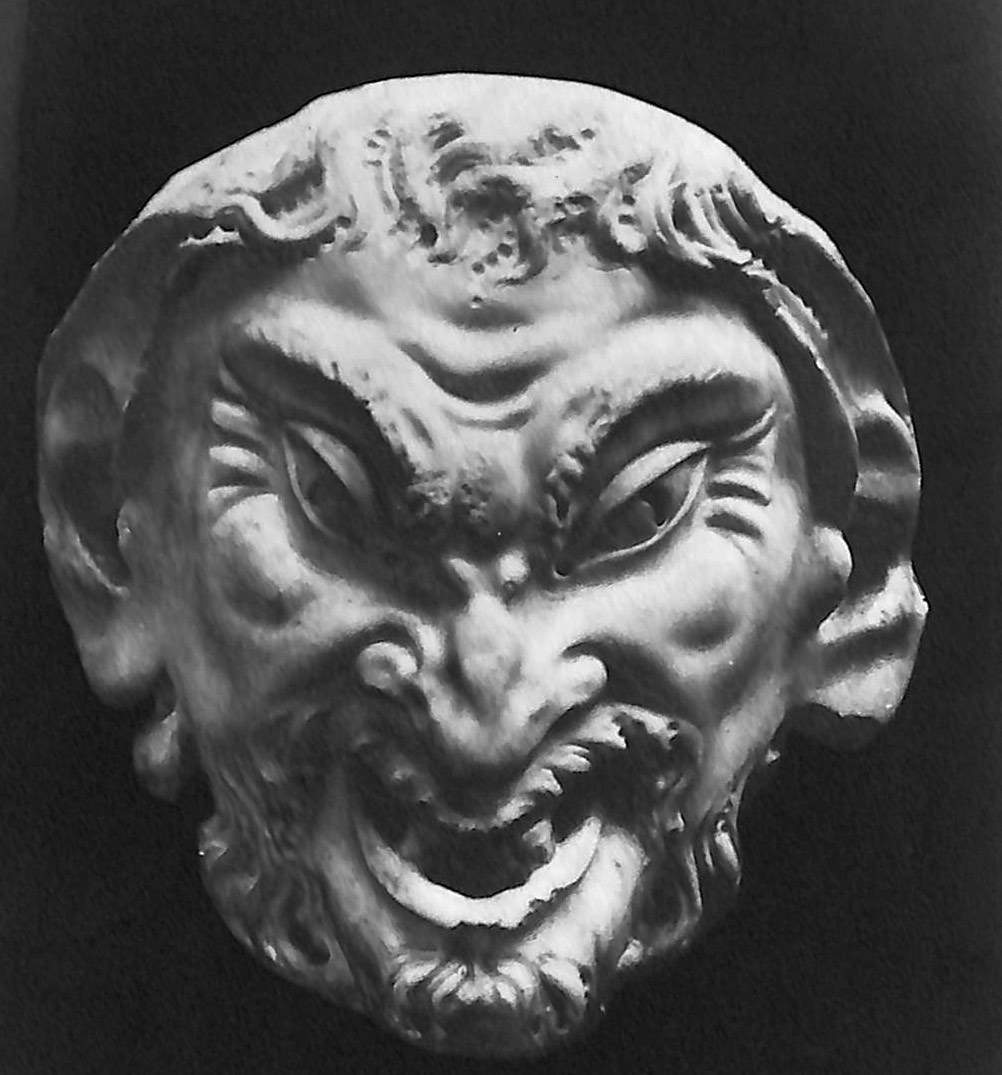

5. Michelangelo (formerly attributed to), Head of a Faun

(c. 1489; marble; location unknown)

The so-called Faun ’s Head was a work once attributed to a very young Michelangelo: before World War II it was kept in Florence at the Museo Nazionale del Bargello. Transferred to Poppi Castle in 1944, to save it from the bombing that would hit Florence, it was stolen by a handful of Nazi soldiers stationed in Casentino. Since then it is not known what happened to it: however, there are rumors that the work was not destroyed and is now in Russia. Unfortunately, so far the search has not yielded any results.

|

| Michelangelo (formerly attributed to), Head of a Faun (c. 1489; marble; location unknown) |

6. Paolo Veronese, Wedding at Cana

(1563; oil on canvas, 666 x 990 cm; Paris, Louvre)

A true “forbidden dream” of many Venetians, Veronese’s Wedding at C ana is perhaps the most famous of the works stolen by Napoleon during the Italian campaign of 1796-1797. In ancient times, the large painting, nearly nine meters wide, was located in Venice, in the basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore on the island of the same name (today an equally sized copy stands in its place). Even after the fall of Napoleon, the work was never returned and even today it is in the Louvre, in the same room that houses Leonardo da Vinci ’s Mona Lisa (which, by contrast, is the rightful property of France). Although we are unlikely to see it return to Italy, “hopes” have increased in recent years: in 1994, the then director general of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Francesco Sisinni, believed that there were cultural conditions for its return. Later, in 2010, historian Ettore Beggiatto, former Veneto regional councillor for public works and regional councilor for fifteen years, wrote a letter to then première dame Carla Bruni urging the return of the work. However, it is also necessary to point out that no official action was ever taken to encourage the return of the Wedding at Cana to Venice.

|

| Paolo Veronese, Wedding at C ana (1563; oil on canvas, 666 x 990 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

7. François Gerard, Portrait of Camillo Borghese

(c. 1810; oil on canvas; New York, The Frick Collection)

The work is a very elegant portrait of Prince Camillo Borghese by François Gérard, one of the best pupils of Jacques-Louis David, and among the leading French neoclassical painters. The work, which at the end of 2017 was owned by an Italian gallery, one of the most prestigious worldwide, was sold to the Frick Collection in New York: according to Il Sole 24 Ore’s reconstruction, the Superintendency had first given the go-ahead for the export, but then retraced its steps by revoking it (due to some omissions in the documents: it was, however, a well-known and already published work) in an attempt to keep what was a rare testimony of the highest quality to the work of a French artist of the Napoleonic period in Italy from leaving its borders. Thus, a “tug-of-war” (so Il Sole 24 Ore) ensued in the summer of 2018 between the gallery, which claims its conduct is legitimate, and MiBAC, which aims to get the work back in.

|

| François Gerard, Portrait of Camillo Borghese (c. 1810; oil on canvas; New York, The Frick Collection) |

8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 The Italian Old Master Works of Art at the National Museum in Belgrade.

These are eight works from various periods (but all ancient) currently housed at the National Museum in Belgardo: they are Paolo Veneziano’s Madonna and Child, Spinello Aretino’s Madonna and Child, a triptych by Paolo di Giovanni Fei, theAdoration of the Child with Angels and Saints of the 15th-century Ferrara School, Vittore Carpaccio’s St. Rocco and St. Sebastian, Titian’s Portrait of Cristiana of Denmark, and Tintoretto’s Madonna and Child with Senator. These are paintings looted by the Nazis in Italy during World War II, and then somehow ended up in Serbia. In the last days of 2017, the Bologna Public Prosecutor’s Office ordered the seizure of the works, requesting their return to Italy (however, the legislative process had already started in 2014): however, Belgrade has always opposed the return of the works, which have not yet returned. Currently, negotiations between the two countries are still ongoing.

|

| Tintoretto, Madonna and Child with Senator (1564-1567; oil on canvas, diameter 156 cm; Belgrade , Narodni Muzej) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.