Three scholars have discovered a fragment of the star catalog of Hipparchus of Nicaea (Nicaea, c. 190 B.C.E.-Rhodes, c. 120 B.C.E.), a famous Greek astronomer who is believed to have been the first to map the stars. His catalog of the stars that can be seen in the night sky was thought to have been lost: scholars Victor Gysemberg of the CNRS (National Research Center of France), Peter J. Williams of the Tyndale House research center in Cambridge and Emanuele Zingg of the Sorbonne in Paris have instead found the star catalog hidden literally under the pages of a Christian manuscript from 337 AD.C. from the Greek Orthodox monastery of St. Catherine’s on Mount Sinai in Egypt: the sheets on which Hipparchus’s star catalog was compiled were in fact reused to produce a new text, the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, a palimpsest (i.e., an ancient manuscript whose original text was erased to reuse the sheets) containing collection of writings in Syriac. For astronomical historian James Evans, who submitted his opinion to the journal Nature, this is a “rare” and “remarkable” discovery.

“The lost star catalog of Hipparchus,” write Gysemberg, Williams and Zingg in their scientific study, published in the Journal for the History of Astronomy, "is famous in the history of science as the first known attempt to record accurate coordinates of many celestial objects observable with the naked eye. However, in contrast to Ptolemy’s later star catalog as preserved in the Almagest and Handy Tables, direct evidence for Hipparchus’ catalog is scant. His only extant evidence is the Commentary to the Phaenomena, a discussion of the earlier writings on positional astronomy by Eudoxus of Knidos and Aratus of Soli. Only a few references in later authors reflect stellar coordinates dating back to Hipparchus (found mainly in theAratus Latinus, a Latin translation of the Phaenomena, an astronomical poem by Aratus, and in related material)."

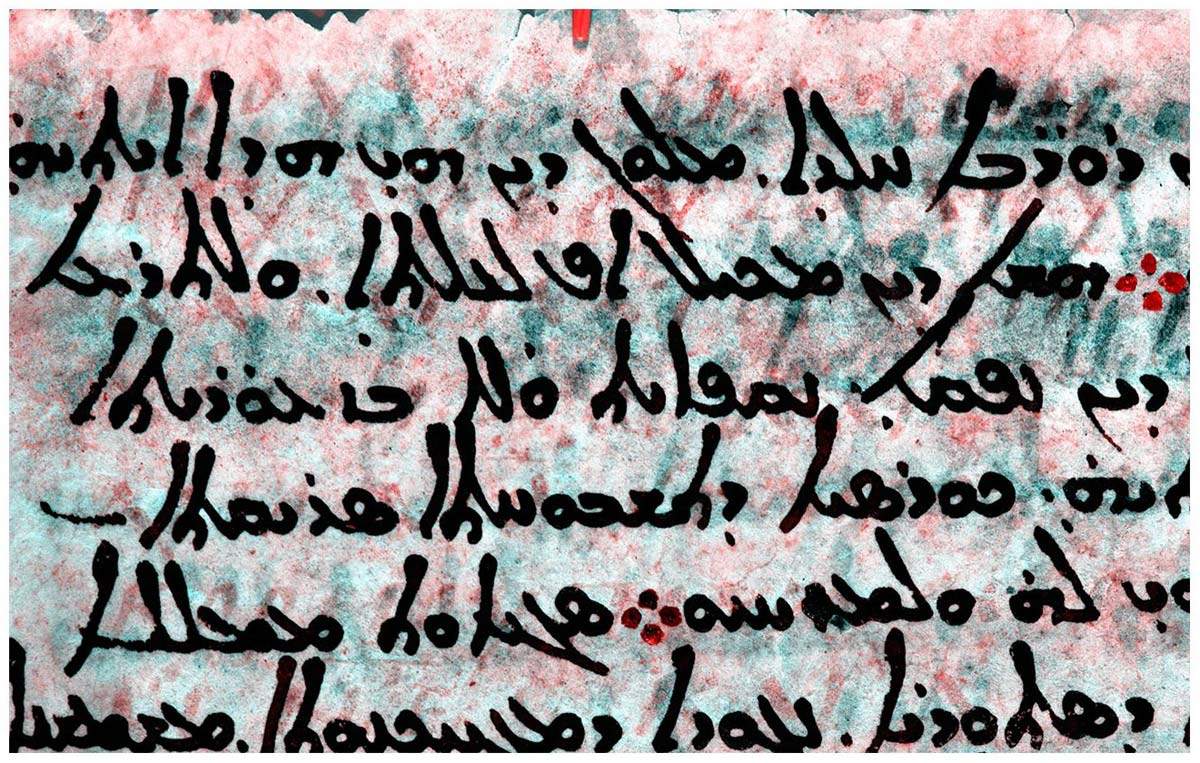

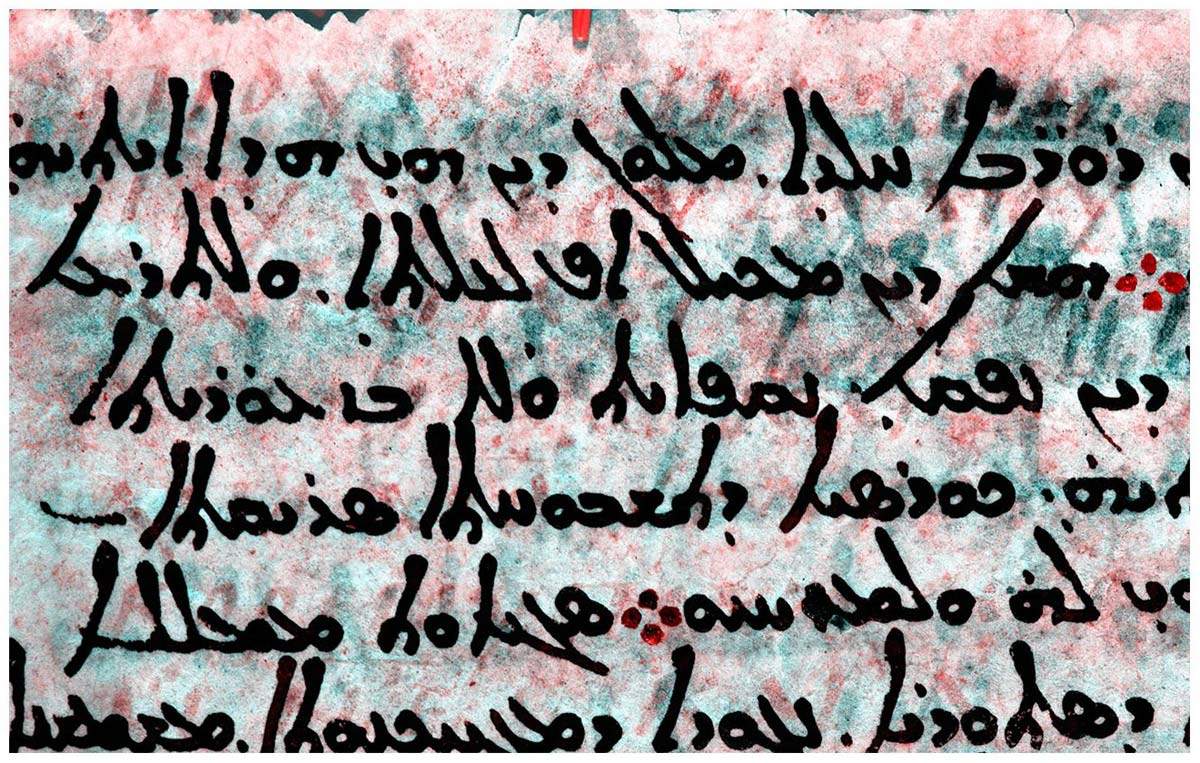

Through multispectral imaging (a digital analysis technique that probes images to observe details impossible to see with the naked eye) of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus, new evidence for the existence of the stellar catalog was obtained. It all started with an observation, dating back to 2012, by Jamie Klair, then an undergraduate student at Cambridge University, who first noticed the astronomical nature of some of the Greek words glimpsed among those in the rewritten text (he was studying the Christian manuscript as part of a summer project), while Peter Williams first observed the presence of astronomical measurements in 2021. Indeed, some of the folios in this manuscript (those ranging from 47 to 54 and folio 64) are derived from what was originally an ancient codex containing Aratus’ Phaenomena and related material.

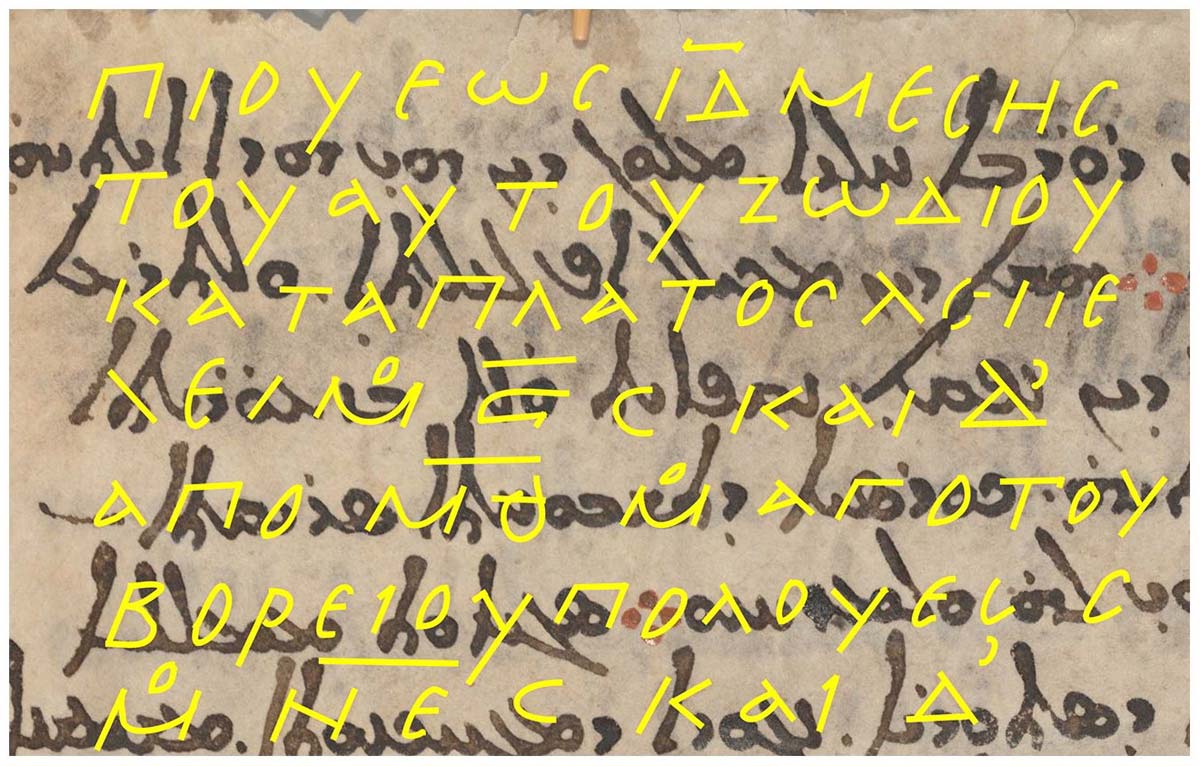

Thus, in 2017, the pages were analyzed with the technique of multispectral imaging: it was necessary to develop different algorithms that, after numerous tests on different wavelengths and different light conditions, would best reveal the text that was hidden among the pages reused by the copyists who wrote the Codex Climaci Rescriptus. From these analyses it was possible to obtain evidence of the existence of Hipparchus’ stellar catalog. In particular, the surviving passage, which put together is about a page long, indicates the length and breadth in degrees of the constellation of the Corona Borealis (in the original Greek text or stéphanos en to boréio), and provides the coordinates for the stars at its northern, southern, eastern, and western ends: “The Corona Borealis, located in the northern hemisphere,” Hipparchus’ text reads, “in length goes from 9°¼ from the first degree of Scorpio to 10°¼ 8 in the same zodiacal sign (i.e., in Scorpio). In width it extends 6°¾ from 49° from the North Pole to 55°¾. Within it, the star (β CrB) to the west next to the bright star (α CrB) leads (i.e., is the first to rise), being 0.5° in Scorpio. The fourth star 9 (ι CrB) to the east of the bright one (α CrB) is the last (i.e. to rise) [...] 10 49° from the North Pole. The southernmost (δ CrB) is the third counting from the bright one (α CrB) to the east, which is 55°¾ from the North Pole.”

Hipparchus, Nature explains, “was the first to define star positions using two coordinates and to map stars across the sky. Among other things, it was Hipparchus himself who first discovered the precession of the Earth and modeled the apparent motions of the Sun and Moon. Gysembergh and his colleagues used the data they discovered to confirm that the coordinates of three other star constellations (Ursa Major, Ursa Minor and Draco),” those found in theAratus Latinus, must also come directly from Hipparchus. “The new fragment makes it much, much clearer,” says Mathieu Ossendrijver, historian of astronomy at the Free University of Berlin. “This stellar catalog hovered in the literature as something almost hypothetical has now become very concrete.”

The three scholars believe that Hipparchus’s star catalog, like Ptolemy’s, would have included observations of almost every star visible in the sky. Without a telescope, Gysembergh says, he must probably have used a diopter or armillary sphere. According to James Evans, the discovery “enriches our picture of Hipparchus. It gives us a fascinating look at what he actually did.” And in doing so, it sheds light on a key development in Western civilization, the “mathematization of nature,” in which scholars seeking to understand the Universe have moved from simply describing the patterns they have seen to the goal of measuring, calculating and predicting. Now, the hope of scholars is that as imaging techniques are developed and improved, it will be possible to arrive at further discoveries previously thought unthinkable. Not least because there are still several parts of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus that have not yet been deciphered. It is also possible, according to the three scholars, that other pages of the stellar catalog survive in St. Catherine’s library, which contains more than 160 palimpsests. Studies to read the deleted texts have already revealed previously unknown Greek medical texts, including drug recipes, surgical instructions and a guide to medicinal plants. Indeed, multispectral imaging of palimpsests is opening up a rich new strand of ancient texts in archives around the world. “In Europe alone, there are literally thousands of palimpsests in major libraries,” says Gysembergh. “This is just one case, very exciting, of a research possibility that can be applied to thousands of manuscripts with surprising discoveries every time.”

|

| Fragment of the first star map, Hipparchus' catalog, believed lost, discovered |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.