by Redazione , published on 07/01/2021

Categories: News

/ Disclaimer

A number of works, including paintings and sculptures, that tell the story of the United States have, in spite of themselves, become the protagonists of the assault on Congress by pro-Trump troublemakers. Here are what symbols they have violated through their action.

There are several works of art that they despite themselves were the backdrop in yesterday’sassault on the U.S. Congress. The troublemakers pro-Trump protesters, who entered the star-spangled symbol of democracy by forcing their way in, in some cases had their pictures taken (and in other cases simply ended up there, creating alienating effects) in front of evocative works of art, which tell the story of the U.S. and the birth of its democracy, one of the oldest in the world. One of the photographs that has gone around the world captures a moment in the Capitol rotunda, the circular environment topped by the recognizable dome of the neoclassical building that houses Congress. There a protester can be seen smiling at the camera waving and carrying away, over his shoulder, and in a pose that elicited hilarity from many, the lectern of the current Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives (one of the two branches of Congress, similar to our House of Representatives), Nancy Pelosi.

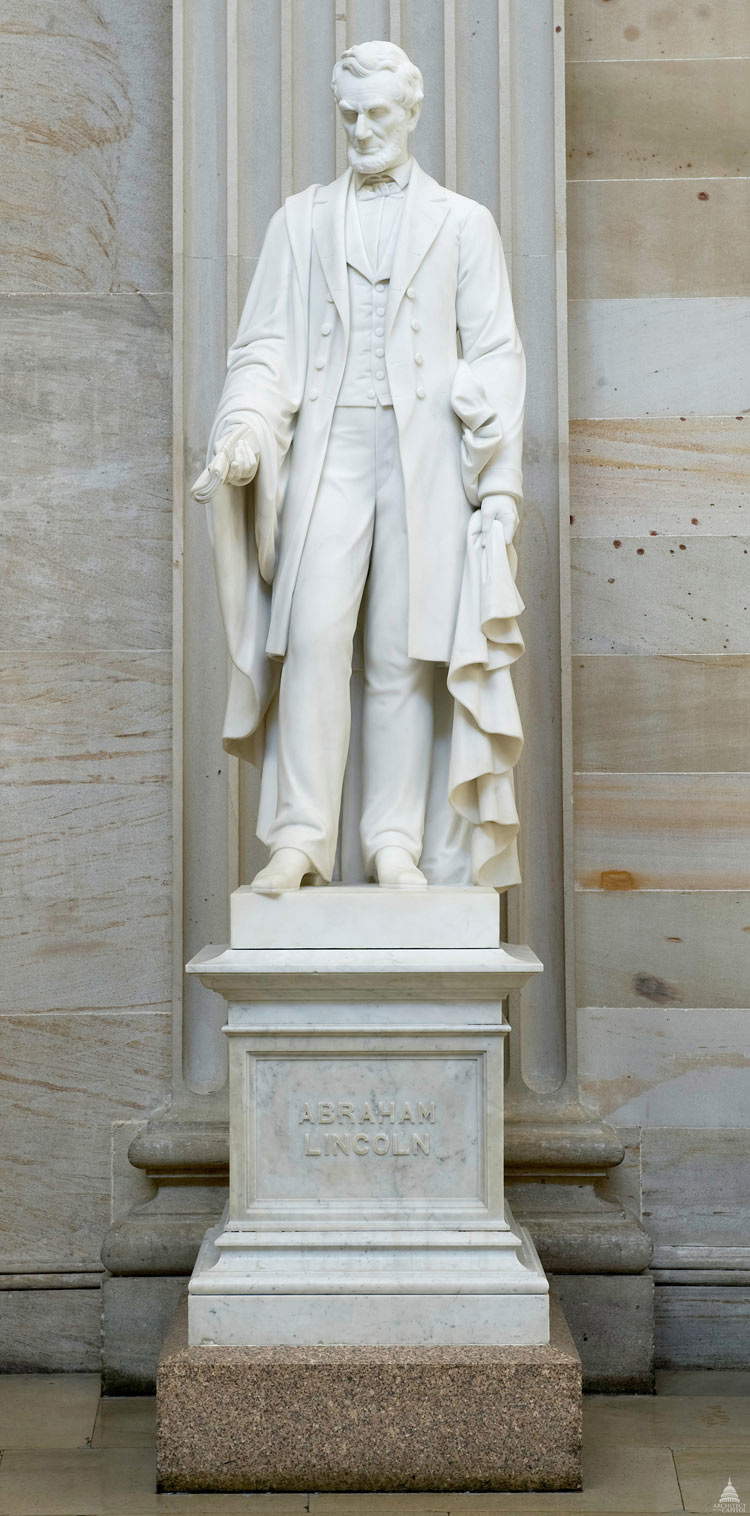

Behind her, a painting and three sculptures tell of as many important moments in U.S. history: the painting, in particular, is the work of one of the greatest U.S. history painters, John Trumbull (Lebanon, 1756 - New York, 1843), and dates from 1817: it depicts a decisive moment in the American War of Independence, namely the Surrender of General John Burgoyne, the commander of the British army, an opponent of the Americans. It was an important event because it would sanction the entry of France (alongside the United States) into the war, which ended with the recognition of the independence of the thirteen colonies, the founding core of the United States, from the former mother country: the surrender came at the end of the Battle of Saratoga (1777), and in Trumbull’s depiction we see in the center General Horatio Gates, a Briton who joined the cause of the U.S. insurgents, rejecting the sword of surrender offered by Burgoyne, inviting him back into his tent. The statues flanking the monument are, from left, that of Alexander Hamilton, revolutionary, constituent father and first secretary of the Treasury, depicted by Horatio Stone (Jackson, 1808 - Carrara, 1875) as he holds the Federalist Papers, the writings drafted to promote the ratification of the Constitution (the same one trampled on by the troublemakers); that of Ulysses Grant, hero of the Civil War (he was one of the leading Unionist generals, and contributed decisively to the Northern victory) as well as the 18th president of the U.S., from 1869 to 1877, depicted by Franklin Simmons (Webster, 1839 - Rome, 1913); that of Abraham Lincoln, 16th president (1861 to 1865), a prominent figure in American history and a symbol of national unity, depicted by sculptor Vinnie Ream (Madison, 1847 - Washington, 1914), and commissioned when, moreover, the artist was only eighteen years old.

|

| Attack on the United States Congress. Ph. Wim McNamee / Getty |

|

| John Trumbull, Surrender of General Burgoyne (1817; oil on canvas, 370 x 550 cm; Washington, Capitol) |

|

| Horatio Stone, Monument to Alexander Hamilton (1868; marble; Washington, Capitol) |

|

| Horatio Stone, Monument to Alexander Hamilton (1868; marble; Washington, Capitol) |

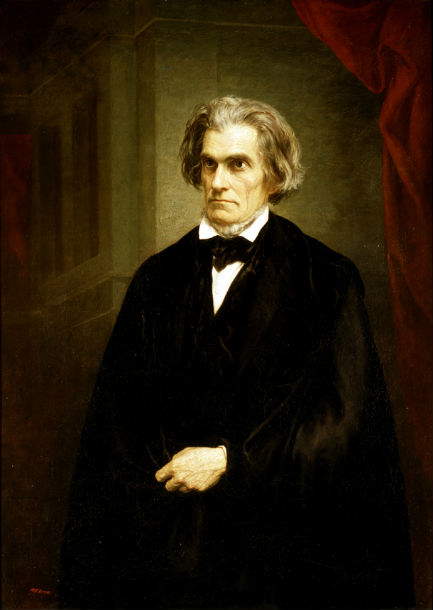

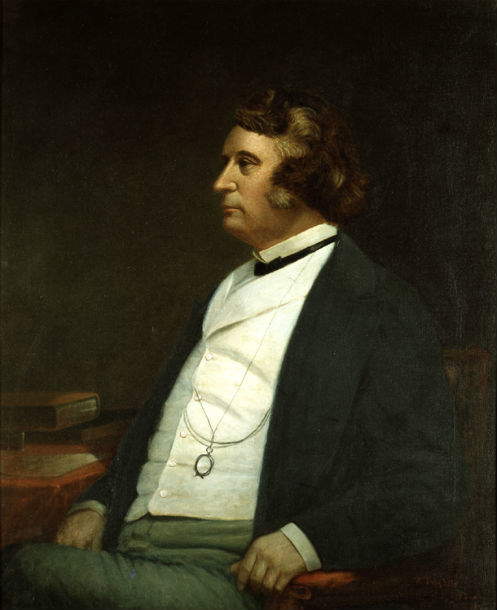

While the lectern remover probably ended up quite unwittingly among some important pieces of U.S. history, reduced to a mere backdrop for his speckled photograph, others may have had some images taken aware of the works they had beside or behind them. Another of the most shared photographs on social media, for example, is of a man wandering through the halls of the Capitol with the flag of the Confederates, one of the two sides that fought the Civil War of 1861-1865 (the very faction defeated by Grant and Lincoln): many media outlets report that it had never happened in American history for the Confederate flag to enter the Capitol, and it is considered a serious act because that flag is now considered a symbol of white supremacy and political exclusion of people of color. The man waves it between two paintings depicting two figures who were opposing souls of the events that led to the Civil War.

On the left is a portrait of John Caldwell Calhoun, a circa 1858 painting by Henry F. Darby (1829 - 1897): a senator from South Carolina and later the seventh vice president of the United States, Calhoun is best known as a champion of the southern United States (his beliefs are believed to be behind the secession of the South from the Union states in 1860-1861: Calhoun, however, never saw it because he died in 1850), and also as an advocate of slavery, which he considered “a positive good” that could benefit both slaves and their masters. On the right, however, is a portrait of Charles Sumner, by Walter Ingalls (Canterbury, 1805 - Oakland, 1874), a Republican senator from Massachusetts and, unlike Calhoun, a staunch abolitionist and antislavery advocate, so much so that in 1856 he was wounded by Southern Congressman Preston Smith Brooks in the Senate chamber. In fact, the rival struck him two days after Sumner delivered a speech that has gone down in history as “the crime against Kansas,” with a strong anti-slavery bias.

|

| Attack on the U.S. Congress |

|

| Henry F. Darby, Portrait of John C. Calhoun (c. 1858; oil on canvas, 126.4 x 90.5 cm; Washington, Capitol) |

|

| Walter Ingalls, Portrait of Charles Sumner (1873; oil on canvas, 111.4 x 89.9 cm; Washington, Capitol) |

Finally, in the last photograph showing the troublemakers “performing” in front of the works of art, one observes a Trump supporter, the one with the bushy beard, dressed in a sweatshirt and red baseball cap, who in other photos appears together with the character dressed as a bovine with horns and fur, waving a “Trump is my president” flag in front of a painting that is extremely significant and symbolic for yesterday’s events: this is the Battle of Lake Erie, painted in 1873 by William Henry Powell (New York, 1823 - 1879). The battle is part of the so-called “War of 1812,” a conflict fought between 1812 and 1815 between U.S. and British forces because of some economic and trade tensions between the United States, born just a few years earlier, and the United Kingdom. The Battle of Lake Erie was fought in 1813 on the shores of the lake of the same name near Put-in-Bay, in the state of Ohio, and was a naval battle that ended in victory for the Americans.

The work is significant because it depicts one of the last major American victories before the British mounted a sustained campaign along the U.S. coastline, which then ended with the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815, which marked the end of the war (it was won by the Americans). Thanks to the victories after the Battle of Lake Erie, the British, in August 1814, were able to take New York and occupy Washington, resulting in a large-scale fire known as The Burning of Washington, during which the British set fire to the White House (it was rebuilt in its present form between 1815 and 1817) and managed to enter the Capitol, which was occupied, looted, and then also burned. In American history, after the sack of 1814, the Capitol had not suffered any more major attacks until the one on January 6, 2021.

|

| Attack on the U.S. Congress. Ph. Wim McNamee / Getty |

|

| William Henry Powell, Battle of Lake Erie (1873; oil on canvas, 510.9 x 811.5 cm; Washington, Capitol) |

|

| Paintings of the assault on Congress: which symbols were violated by pro-Trump troublemakers |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.