A Russian oligarch is suing one of the world’s leading auction houses. The charge brought by Dmitry Rybolovlev (a potassium fertilizer entrepreneur, owner of the French soccer team Monaco, and ranked by Forbes as the 428th richest man in the world) against Sotheby ’s is that he inflated the prices of some artworks he purchased. The trial began the day before yesterday, Jan. 8.

According to Rybolovlev’s lawyers, Sotheby’s allegedly acted in complicity with Swiss art adviser and dealer Yves Bouvier, an adviser to Rybolovlev in many of his transactions, hired to get the works at the best price, and against whom the oligarch has already taken several legal actions in past years. Bouvier is being challenged over transactions involving 38 works of art, which resulted in Rybolovlev’s allegedly excessive outlay of $1 billion.

Among the disputed transactions is one for a Head by Amedeo Modigliani, a sculpture purchased in 2013 by the oligarch for $83 million: Bouvier negotiated the transaction in his capacity as Rybolovlev’s adviser, claiming, according to the legal documents, that the figure of 83 million was the lowest figure the seller was willing to accept in order to surrender the work, only, again according to the documents, the seller was Bouvier himself, but Rybolovlev’s lawyers claim that their client would not have received this information and would have lost millions of dollars because of it.

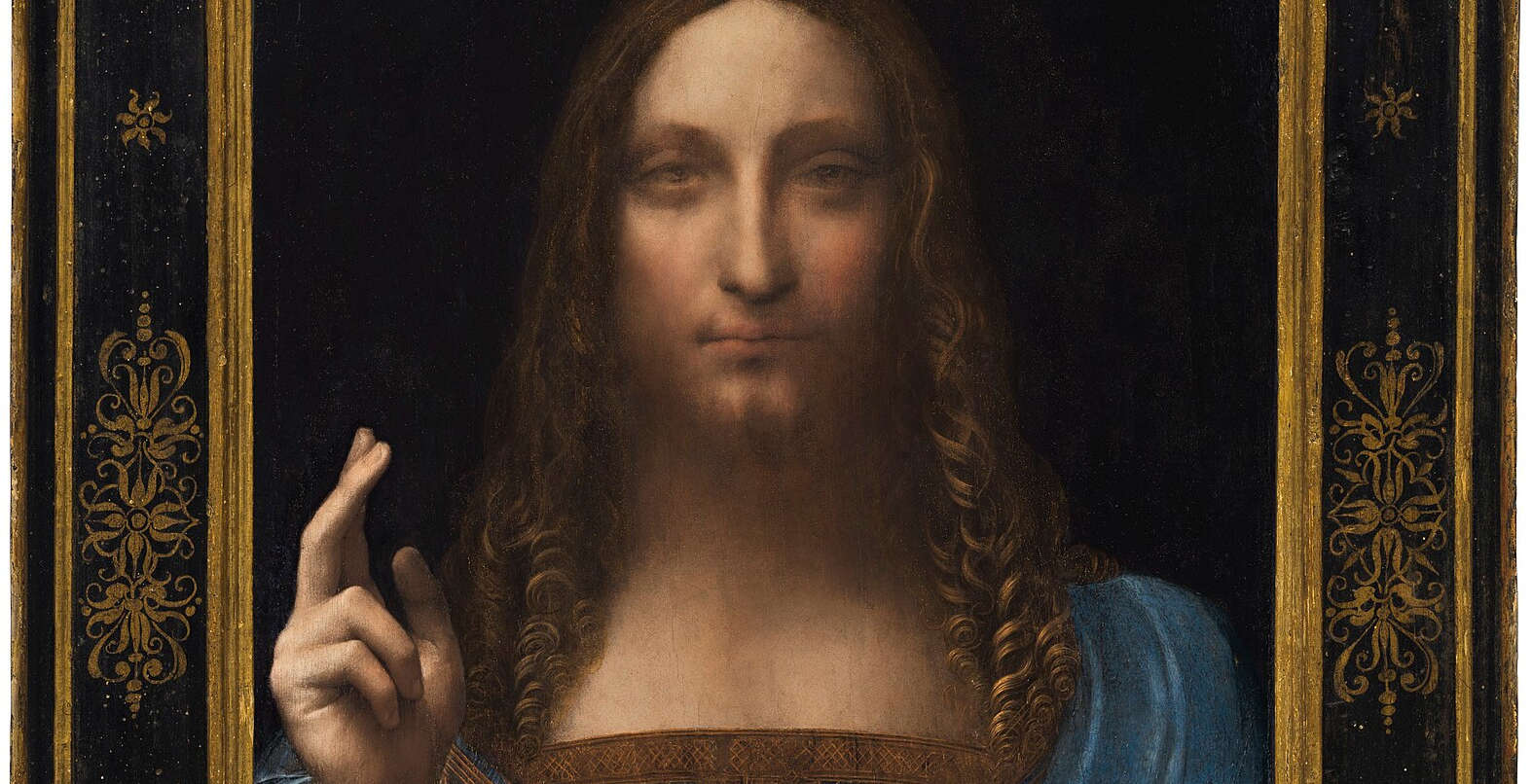

And again, the transaction related to the Salvator Mundi, the work attributed to Leonardo da Vinci that later went to auction at Christie’s in 2017, where it fetched $450.3 million, becoming the most expensive auction in history (money collected by Rybolovlev, who was the owner of the Salvator Mundi), is also disputed. Four years before this event, in March 2013, Rybolovlev was reasoning about a possible purchase of the Salvator Mundi, which at the time was valued at much lower figures than its 2017 adjudication. According to the New York Times, a Sotheby’s representative reportedly went to see the Salvator Mundi in person at a New York apartment along with Rybolovlev and Bouvier. A few weeks later, Bouvier, in an email sent to an assistant to the oligarch, said the then-owner of the Salvator Mundi had turned down offers between $90 million and $125 million. However, according to court documents, Bouvier allegedly bought the Salvator Mundi through Sotheby’s on May 2, 2013 (at $83 million), and then sold it back to Rybolovlev for $127.5 million.

Two years later, Rybolovlev broke relations with Bouvier after discovering, following a conversation with another adviser, that the price paid for a Modigliani painting had been much higher than the price the seller was willing to accept (and Bouvier would keep the the difference), although by early 2015 he had already begun to suspect his collaborator, and thus requested an appraisal of the Salvator Mundi from Sotheby’s, which suggested a price of 114 million. According to legal documents, it appears that the Sotheby’s appointee who viewed the work along with Bouvier and Rybolovlev asked the colleague who was to estimate the painting to omit any reference to Bouvier’s 2013 purchase.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da VinciAlso according to the oligarch’s lawyers, Sotheby’s allegedly helped Bouvier inflate the works’ valuations, covering up the Swiss dealer’s alleged double-dealing. At present, Bouvier is not a defendant in New York, and in a preliminary decision issued by U.S. District Judge Jesse Furman in March 2023, many of Rybolovlev’s charges against Sotheby’s were being dismissed, either because of the statute of limitations or lack of evidence. However, the judge allowed the jury trial, the one that starts these days, to go forward in relation to four of the 38 works charged (in addition to Modigliani’s Head and Salvator Mundi, there are two paintings, one by Gustav Klimt, Wasserschlangen II, and one by René Magritte, Le Domaine d’Arnheim). Bouvier, as the New York Times reports, has long insisted that he was clear that he was operating not only as a consultant but also as an independent trader, and as evidence he would present sales contracts for Rybolovlev’s first purchases in which it would appear that he was operating openly as a trader, free to charge whatever price the oligarch was willing to pay. Rybolovlev, however, disputes that Bouvier’s role then evolved into that of adviser and agent and cites emails in which Bouvier describes negotiations with sellers that would appear not to have really taken place. Bouvier’s attorneys continue to argue that their client strongly opposes any allegations of fraud and cite the outcomes of lawsuits already filed against him in Monaco, Singapore, and Geneva, which would be evidence that the advisor did nothing wrong. In Monaco, the suit had ended in dismissal. In Singapore, the action had ended with a decision to transfer the proceedings to Switzerland. In Geneva, the last of the ongoing trials between Rybolovlev and Bouvier, the Swiss city prosecutor’s office dismissed the proceedings after the parties informed it that they had reached an agreement in private, and Rybolovlev therefore withdrew the complaint (court costs of 100,000 Swiss francs were awarded to Bouvier, however). Sotheby’s involvement is also nothing new: in 2016, a New York court invited the auction house to rule on the Salvator Mundi transaction. Sotheby’s denied that it was part of any scheme perpetrated by Bouvier to defraud both the sellers of the painting in 2013 and Rybolovlev. The oligarch then sued Sotheby’s in 2018, arguing that the auction house had nonetheless knowingly and intentionally made the fraud possible because it knew how much Bouvier had paid the original sellers. A subsequent ruling in New York forced Sotheby’s to produce criminal documents already used in the Munich and Geneva proceedings, a decision the auction house opposed on grounds of confidentiality. Then, in 2023, Judge Furman’s decision to start the trial concerning the four works.

“At trial,” attorney Marcus Asner, one of Sotheby’s lawyers, told the New York Times, “the plaintiff will have to show that Sotheby’s somehow knew that Bouvier was lying to Mr. Rybolovlev about how much he, Bouvier, had paid for the works when he bought them. But there is no evidence that Sotheby’s knew Bouvier was lying.”

Regardless of the outcome of the trial, as the New York Times notes, the trial is expected to provide a rare window into the often secretive inner workings of the art trade, where even buyers rarely know from whom they are buying treasures worth a small fortune. Indeed, experts say the jury trial could provide new guidelines for a more transparent art market. “There is so much secrecy in the art world that buyers sometimes don’t know the amount of money earned by others in transactions,” Leila A. said, also to The New York Times. Amineddoleh, a lawyer specializing in art and cultural heritage. “So this case will help clarify the responsibilities and fiduciary duties owed to clients by dealers and auction houses.”

|

| Russian oligarch sues Sotheby's, accused of inflating artwork prices |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.