“Creating sculpture means existing in a place”: so said Volterra artist Mauro Staccioli. But of the existence and enchantment of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s monumental Venus of rags , installed in Naples’ Piazza Municipio last June, little remains today. The fire that caused the work’s destruction cannot but confront us with a profound reflection about the role of public art today, especially in Italy, as well as make us question whether such artistic practice can be considered still today the engine of a collective critical action capable of stimulating reflection and dialogue with the context.

It must be emphasized that the term ’public’, associated with the art world, acquires a decisive weight and its meaning should not, as has happened in the past, be associated with the free usability of the artistic artifact, as much as with its being conceived and constructed for a specific collectivity and for a specific place. It is, if anything, an ambivalent expression that designates a wide variety of artistic forms, each with a history and with multiple and different meanings that nowadays live within the urban and landscape context.

Sculpture has long been thought to be the product of an individual and autonomous act of expression, “what you bump up against when you step back to look at a painting from a greater distance,” to borrow Barnett Newman’s words, and its function referred primarily to a decorative purpose. For a long time it turned out to be exclusively an exercise in celebratory rhetoric, and it was only from around the late 1960s onward that a decisive change of course took place, concretized in the spread of numerous artistic practices, based on participation and collaboration, and with which new forms and creative expressions, free from the constraints and misunderstandings of the museum space, began to be experimented with within the urban space.

Over the past decades, the concept of ’public art’ has thus taken on ever-changing declinations, but of one aspect we need to be certain: spatial location is not a sufficient element to identify artistic practice as ’public,’ since, in addition to physical accessibility, attention must also and above all be turned to the relationship between the work and the public and to the immaterial values of society. The space must become a place of interaction, linked to the social context and the community, and encourage active participation, even of specific audiences normally outside the art system.

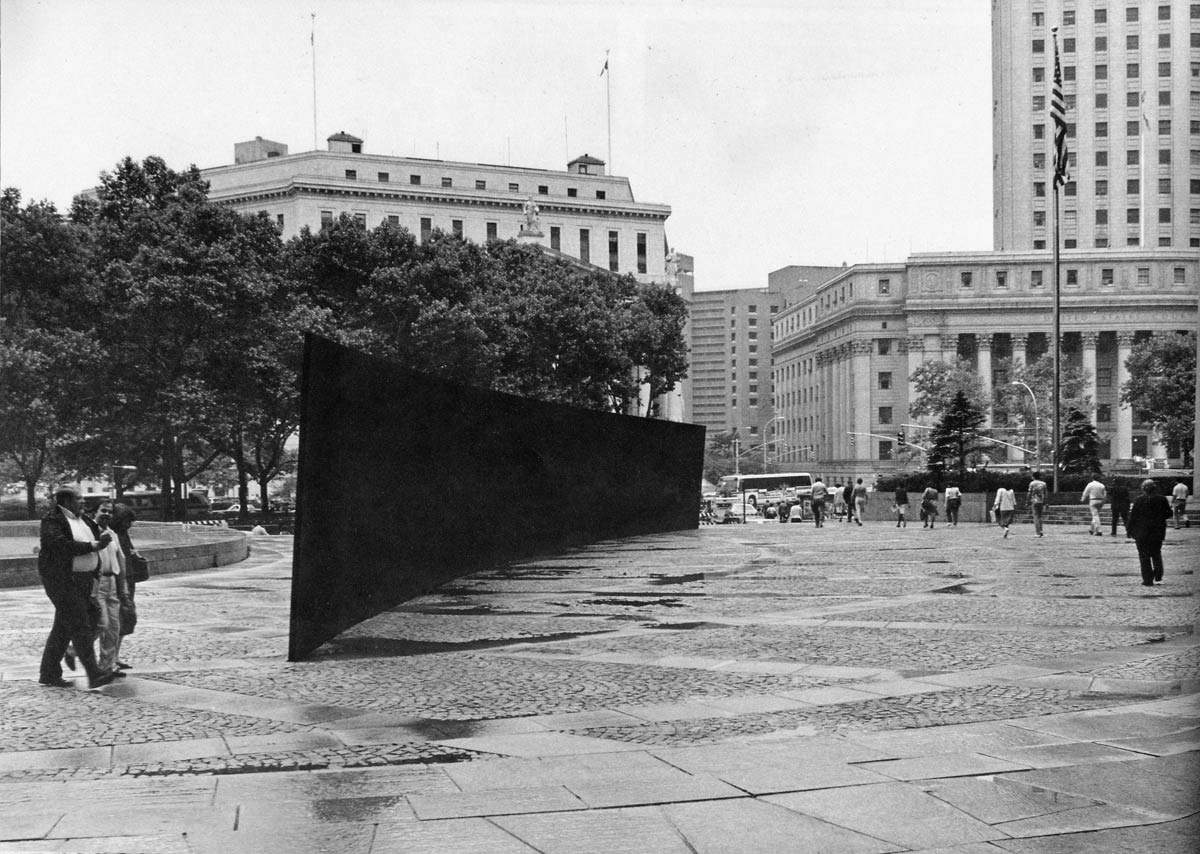

When it comes to public art, a very recurring issue concerns the fact that artistic interventions made in the public sphere should be designed for a totally different audience than the museum: a broader public, not made up of active cultural consumers, a public that sometimes does not accept proposed interventions within its territory; therefore, it should be pointed out that the impressions and responses of the public following the creation of a site-specific artwork within a specific environment can decisively influence the fate of the art intervention itself. The critical issues, related to public consensus, that an artistic intervention may manifest when it is placed in a specific space can be diverse: one need only think of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, a monumental work installed in 1981 at Federal Plaza in Manhattan and promptly had it removed following an accusation of privatization of public space, or the intense debate generated by the work L. O.V.E. (2010) by Maurizio Cattelan, which stands in Piazza Affari in Milan in front of the Stock Exchange building.

It is then well known by now the numerous complexities that, often, artists and non-artists are required to face when attempting to initiate a dialogue with possible institutional interlocutors, and it is also well known that these problems are often accentuated by numerous problems related to the relationships between regulatory situations due to which art practices struggle to find room for action. Although these are not insignificant problems, there are undoubtedly new critical issues, related to the changes in the reality in which we live, that have decisively affected the fate and acceptance of public art within today’s society. Particularly affected by this is the concept of participation: in this frenetic society we are increasingly accustomed to the immediacy and timeliness with which we store external messages, and contemporary art, for many, turns out to be something non-immediate, unapproachable. For this reason, it is often given a superficial glance, as being unable to offer immediate, if ephemeral, satisfaction.

In the face of well-known issues, the fact remains that acts of vandalism against works of art installed in public space are nothing more than the manifestation of rampant weakness and ignorance, which nonetheless also approach a social critique already embodied by the work of art itself. In the light of so many different positions and testimonies on public art, it seems clear that the latter should be considered as an engine of landscape and urban transformation only if there is a true dialogue between art, urban context and the public, thus fulfilling a specific function, namely that of raising community awareness of art and culture for the development of an awareness not only towards artistic expressions, but also towards diversity. Public art must mirror the present, an art for all and by all, where the work becomes medium and the public becomes audience.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.