One of our readers, Ornella Spada, sent us a response toTomaso Montanari’s editorial published last April 5 on his blog Articolo 9: the topic was the “Primavera di Boboli” project, the restoration of the Garden made possible by a donation from the fashion house Gucci, which will organize a fashion show at Palazzo Pitti on May 29. As the editorial staff of Finestre Sull’Arte, we would like to make it clear that we do not agree with the contents of the article and we dissociate ourselves from it: however, our site, in its tradition of welcoming and promoting pluralism, is notoriously open to all contributions from anyone who wants to participate in discussions around the state of cultural heritage in our country. The author of the following contribution, Ornella Spada, is a graduate of Columbia University and has worked at the Guggenheim in New York and the Gagosian Gallery.

|

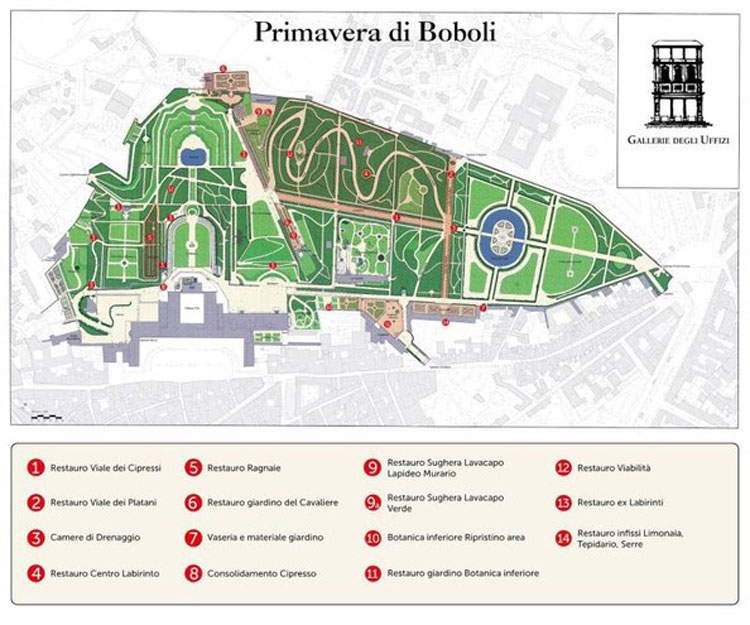

| The project Primavera di Boboli |

Florence prostitute is the title with which Tomaso Montanari, art historian, professor of History of Modern Art at the University of Naples Federico II and columnist, comments on Repubblica’s Articolo 9 blog on the agreement between Gucci, the City of Florence and the Uffizi Galleries. The CEO of the famous fashion house Marco Bizzarri, together with the director of the Uffizi Galleries Eike Smidt, Mayor Dario Nardella and Minister Dario Franceschini, announced that they have donated 2 million euros to the museum for the restoration and enhancement of the Boboli Gardens. In exchange for the donation, Gucci was granted the concession of the Palatine Gallery of Palazzo Pitti for the fashion show to be held on May 29.

Tomaso Montanari sharply criticizes the Italian institutions’ attitude of openness and defends that held by Greece in the face of the fashion house’s request to use the Parthenon for the same event. The Central Archaeological Council of Greece had peremptorily refused the concession of the Athens Acropolis to Gucci.

Screwed up is also the adjective the art historian uses for the Pitti Palace, called the most screwed up museum in Italy, between bachelor parties of millionaires, loans imposed by politics, designer exhibitions, this is not a cultural project, but prostitution here we are faced with large multinational corporations using the commons as a location to better sell their products.

The professor’s rather romantic and aggressive stance fails to recognize some of the more realistic aspects that have always belonged to the world of art and that have always seen him approach the world of economics and finance. I will try to dismantle the historian’s argument at its most salient points.

Montanari calls it muckraking, but what is happening at the Palatine Gallery is the direction that all places of culture in the world are following, from the Louvre in Paris to the Met in New York. Museums are turning into liquid entities where art intersects with multiple and varied cultural and commercial initiatives. There are several reasons for this, a first one is economic: museums in fact, in other countries, do not enjoy public funding (not entirely as in America or are very meager as in some European countries) and for years have been inventing self-financing systems to avoid closing budgets in the red and promote innovation and culture. Hence the promotion of a strong merchandising, branding and public relations policy with the renting of special spaces for gala events and fundraising. The fact that a museum’s budget is positive and that there are margins means that there can be investment: it means for example promotion of young artists, investment in technology for better enjoyment of for example artworks with consequent educational benefits for visitors of all ages, from children to adults, and above all more job opportunities for young people. If the price to be paid for all this is a Gucci fashion show, I think the problem lies rather in not having thought of this earlier, and not having tried to promote a long-standing affiliation with Italian fashion houses in order to get it all, those 56 million naively refused by Greece[editor’s note: figure later denied by Gucci].

The professor goes on to say, It’s a kind of self-glorification of the present, climbing on the shoulders of the past: cheap self-promotion, through a historical forgery. And if we find the same clothes at Pitti that populate the windows of the streets we have traveled to reach the museum, what have we done? At stake is not the dignity of art, but our ability to change the world. Cultural heritage is a window through which we can understand that a different past has existed, and therefore a different future will also be possible. But if we turn it into the umpteenth mirror in which to reflect our present reduced to only one dimension, the economic one, we have made medicine sick, we have poisoned the antidote. And what “dialogue” can there ever be between Gucci’s clothes and Andrea del Sarto’s altarpieces, or Raphael’s Madonnas?

The marriage of fashion and museums that sounds so outrageous in the professor’s eyes is routine in the world’s greatest museums. It is repeated every season between Paris and New York, just to mention Proenza Schouler’s show at the Whitney Museum in February 2016 or Louis Vuitton’s show at the Louvre in Paris last March, just to give two examples. In the French capital, the Palais Galliera will become the country’s first permanent fashion museum in 2019 thanks to the invaluable support of Maison Chanel. Not only is fashion one of the most lucrative sources of sustenance for cultural institutions since time immemorial (the most famous designers are collectors and philanthropists: just think of Miuccia Prada, Yves Saint Laurent, and Dries Van Noten) but it is also the subject of some of the most celebrated curatorial projects in contemporary art, just think of Azzedine Alaïa: Couture/Sculpture at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, or the one in honor of designer Alexander McQueen, Savage Beauty, held first at the Met in New York and then moved to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. In the British capital, the show sold more than 480,000 tickets was among the most popular in the history of the museum, which was forced to work around the clock to meet high public demand.

This sort of contamination that Montanari calls muckraking is supported and promoted by the most distinguished modernist and contemporary curatorial theses. Alexander Dorner, Hans Ulrich Obrist, and Okwui Enwezor are some of the many curators to support the theory that technology and globalization have obliterated the distances between different fields of knowledge, and the fact that art cannot be distinguished from other creative expressions such as design, fashion, architecture and film, and video art, for that matter, is a confirmation of this. The professor’s idea of the museum as a dusty place where art is enshrined as absolute truth to understand a different past and future is quite inaccurate. First of all, because art would not be art if it did not reflect who we are: in fact, the high value of artistic expression lies in the representation of the human condition in its essence (both low and high). Second, art has always had an economic dimension. The greatest works of art would never have existed if there had not been patronage to promote artistic talent and finance the creation of works of art. One example above all is Michelangelo and the hard-fought patronage and censorship exercised by the Church against his works. This article would not be enough to list the cases in which art has been joined by personalities from business and finance and rich women and fashion muses. What would have become of abstract expressionism if there had been no Peggy Guggenheim, for example? Today’s global economy has changed only the form and not the substance of things: big money influences the value of artworks and turns artists into millionaire stars. In fact, art is considered by financial experts to be one of the safest assets, whose value increases over time; it is no coincidence that the biggest art collectors are businessmen like Steve Cohen, a loyal client and friend of Larry Gagosian.

To deny this is the historical fallacy that the professor commits: to frame art as an immobile and fixed entity is to deny its inherent capacity to reflect human nature. It is a bit like denying the fact that downtown storefronts display not only articles of clothing but also works of art. Acknowledging these historical, cultural and economic realities is crucial to seeing the connection between Gucci’s clothes and Andrea del Sarto’s Altarpieces or Raphael’s Madonnas that the professor denies but which instead has always existed.

Ornella Spada

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.