Anyone who has had anything to do withcontemporary art (even by simply seeing a picture of a work on Facebook, for example), knows that there are many people who, when confronted with an object whose form is not immediately recognizable and whose meaning is not easily guessed, will flaunt or claim ignorance, will lavish themselves in curmudgeonly comparisons with the art of the past as if a mythical golden age had existed in which all art was better than that of the present day, and perhaps they will even say that the forms of art that are offered to us every day are the exclusive result of a conspiracy perpetrated by the market and critics, who want to impose their tastes and artists on us at all costs.

Reading an article that appeared a few days ago in El País, I certainly did not expect that to cry consp iracy (or “gombloddo,” as it is fashionable to write on social media, to ridicule the conspiracy theses of the plotters) was an author awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010, namely Mario Vargas Llosa, who in his piece entitled El palo de escoba (“The Broomstick,” translated into Italian for Repubblica by Luis E. Moriones) wanted to give us an account of his impressions after visiting the Tate Modern in London. One work, in particular, caught the writer’s attention: he describes it as “a cylindrical handle, probably of a broomstick, from which the ’artist had removed the sorghum or nylon bristles that had made it functional-as an everyday object for household chores-and had painstakingly painted it green, blue, yellow, red and black, in series that followed more or less this order, covering it entirely.” What is irritating is that Vargas Llosa intentionally glosses over the artist’s name and the work (a typical rhetorical device used to debunk the object of his own criticism), even going so far as to flaunt a willingness to deliberately remain ignorant when he says he did not want to find out the author’s name or the title of the object.

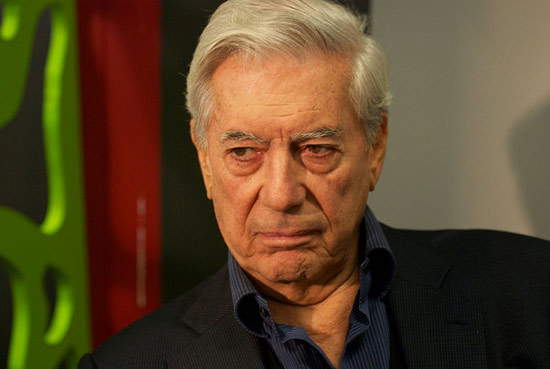

|

| Mario Vargas Llosa. Credit |

The work that would seem to have so disturbed Vargas Llosa’s aesthetic taste, according to at least his description, is obviously not a broomstick: it is the “Round Wooden Bar,” a sculpture by André Cadere made in 1973. It is important to know this not only out of respect for the work, but also because the writer, in the final lines of the article, in commenting on the efforts of a teacher trying to explain the work to a group of children, expresses himself in these terms: “what she was doing was nothing more than contributing to a monumental imbroglio, to a very subtle conspiracy little less than planetary on which galleries, museums, distinguished critics, specialized magazines, collectors, professors, patrons and shameless merchants have agreed to ’deceive themselves, deceive half the world and, in passing, allow a few to line their pockets thanks to such an imposture.’” If Vargas Llosa had taken even just a few minutes to delve into the figure of André Cadere, he would have known that he could not have chosen a more misguided artist as an example of the phantom “monumental hoax” hatched by galleries and critics against the defenseless art-goers. For André Cadere was a proudly anti-establishment artist, crashing other artists’ exhibitions with his round wooden bars for the purpose of provoking the environment, or handing out pompous flyers announcing “presentations of his work” that were really nothing more than walks through the streets of Paris with his bars in hand (in doing so, moreover, Cadere was suggesting that art is something that concerns everyone), or he was mocking the organization of Documenta 5 in Kassel, which had invited him to the exhibition on the condition that he cover the journey from Paris to Germany on foot: he had sent fake postcards of the cities scattered along the way, and had reached Kassel by train. Cadere was, in essence, an independent, untamable artist who was particularly disliked by official critics (and especially by many other artists) precisely because of his mocking attitude: a romantic figure who certainly cannot be considered an example of the “conspiracy of galleries and critics” of which Vargas Llosa speaks.

|

| André Cadere, Round Wooden Bar (1973; painted wood, 155 x 3 x 3 cm; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| AAndré Cadere around Paris with one of his wooden bars. |

It is clear that a good deal of contemporary art is adequately foddered by the market and critics, and that many artists, without good connections, would not be able to get the word out. But neither is it possible to throw all conceptual art inside an improbable soup built, moreover, on completely flimsy foundations (because Vargas Llosa is careful not to try to demonstrate, in a serious way, whether there is anything that holds up the thesis of the “monumental imbroglio”). In fact, Vargas Llosa’s article is flawed in several respects, even on a merely technical level. There is not a single concrete reference to an artist’s name (the first thing they teach in a first-year college communications course is that any assumption must be adequately substantiated), and yet a personal opinion (as to what characteristics a “genuine” work of art should have) is passed off as an absolute paradigm through the use of the present indicative, and finally the only pseudo-historical thesis advanced by the author is entirely grounded (if one can call it that) in indeterminacy: “these things have always happened, no doubt about it, but then, in addition to these, there were certain cities, certain institutions, certain artists and certain critics who resisted, who confronted cunning and lies, denounced them and defeated them. They were part of that demonized elite that the political correctness of our time has put up against the wall.” But by “then” what period is Vargas Llosa referring to? By “certain cities,” which cities does he mean? Which institutions? Which artists? Which critics? Which elites? Have given at least one example!

I don’t criticize Vargas Llosa’s thoughts: onconceptual art he will have his opinion and that’s right. What I criticize is theattitude. It is disconcerting that such far-fetched demonstrations of superficiality and such blatant calls for ignorance come from a writer who has been awarded a Nobel Prize for literature, and who writes in a newspaper read by millions of people who, given the authority the author has earned, will probably take his hallucinating broadsides against conceptual art as gold. Could it be that the conspiracy syndrome is proselytizing even where it was thought it would never arrive? Joking aside, one thing is certain: such articles are not good for either the authors (who lose credibility), the newspapers that publish them (whose spaces are taken up by conspiracy rants that could be done without, even if they are written by Nobel laureates), or the readers (who, after such articles, might safely wonder whether they can continue to trust authors and newspapers).

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.