Fifth leg of the journey in search of animals and fantastic places among the museums of Italy: we move to Molise to see what this small region nestled between the Adriatic Sea and the Apennines has to offer. We remind you that museums and places of culture are safe places to visit, in the company of your family and your children. A project that Finestre Sull’Arte carries out in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture.

This painting by Luca Giordano (Naples, 1634 - 1705) kept at the National Museum of Molise at Castello Pandone in Venafro (Isernia) recounts one of the best-known myths of antiquity, that of the god Pan, the god of woods and pastures, protector of natural creatures, who falls in love with the nymph Syrinx. It is an unrequited love, however: Pan, in fact, has a feral appearance, since he is half man and half goat. Frightened by his appearance, Syrinx asks for help from the Naiads, the sea nymphs, who, in order to remove her from Pan’s attentions, turn her into a marsh reed plant. Pan, not finding her, in order to stop thinking about his love cut the reeds he found on his way and began to blow into the reeds, producing a suave harmony: the god did not know that those notes were produced by Syrinx herself. Thus was born, according to the myth, the Pan flute, also known as the “syrinx.” In Luca Giordano’s painting we see the various stages of the tale condensed into a single moment: the nymph, below, transforming into the marsh reed plant, and the god cutting them to make his own musical instrument.

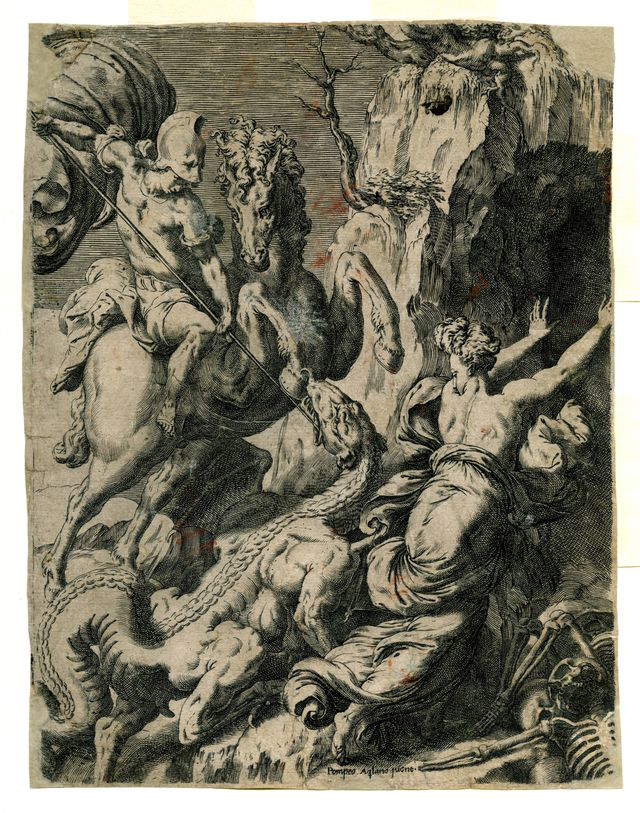

The National Museum of Molise also preserves a burin engraving by Pompeo Cesura also known as Pompeo Aquilano (L’Aquila, c. 1510 - Rome, 1571), an artist from Abruzzo who was much influenced by Raphael Sanzio, which depicts the episode of St. George defeating the dragon and freeing the princess. The saint, as per typical iconography, is on his horse, which is upright on its hind legs, while the dragon is in front of him and is now overwhelmed by his spear: it almost looks like a large crocodile. The princess is on the right, and is depicted with her bare back, leaning against the rock. The excited rhythms, the twisted and sinuous poses, and the composition on diagonal lines are all typical of Mannerist art. The work is part of a collection of drawings, watercolors, and sketches by various artists active between the 16th and 18th centuries that was acquired by the Ministry in 1990: the material, which has been at the Pandone Castle in Venafro since 2015, is displayed on a rotating basis in the halls of the National Museum of Molise.

An oscillum was a small circular sculpture, usually depicting a head, which in Roman times was hung by a rope or chain from trees as a votive gift to a deity. It is not uncommon to find oscilla with fantastic creatures or faces of satyrs, as in the case of this one preserved at the Samnite Museum in Campobasso. Unfortunately, it has not been preserved in its entirety: only the right side remains, but enough to observe the appearance of this creature. Satyrs were creatures that according to myth lived in the woods, had the body of a man and the legs, tail and sometimes (as in this case) even the ears of a goat, and were considered personifications of the generating force of nature. Hanging an oscillum with a satyr’s face thus meant trying to propitiate a favorable season.

Larino, now a village of about six thousand inhabitants about twenty kilometers from Termoli, was in Roman times one of the largest and most flourishing cities in this area of southern Italy. Numerous vestiges of the Roman Larinum have been preserved, starting with the Amphitheater: in addition to the monuments, however, there are many finds from archaeological excavations, most of which are preserved at the Museo Sannitico in Campobasso. One of these is the fragment of architectural terracotta from the forum of Larino, that is, the place where the magistracies and commercial activities of the ancient Roman city were based. It is a terracotta dated to the second century AD where a griffin is depicted, a mythological creature symbolizing the union of earth and air as it summed up the characteristics of the lion and the eagle. A positive fantasy animal, it was a symbol of pride and power. In ancient times it could be depicted in two ways: either as a bird griffin, that is, with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion, or as a lion griffin, with the head and body of a lion and the wings of a bird. The griffon from the Samnite Museum belongs to the second case.

The dragon that stands above the coat of arms on the portal of the Castle of Civitacampomarano tells a very peculiar story, though not so unusual in its time. In 1442, the mercenary captain Paolo di Sangro was leading the army of the Duke of Bari, Antonio Caldora, who was supporting the Angevins against the Aragonese. The night before the Battle of Sessano, which was fought on June 29, 1442, and which pitted the “Compagnia Caldoresca,” or Antonio Caldora’s army, against the Neapolitan army led by Alfonso V of Aragon, Paolo di Sangro secretly made an agreement with the Aragonese, who promised him fiefs and privileges in case he switched sides. The next day, Paolo di Sangro was seen fighting together with the Aragonese, and the betrayal was decisive, because the Neapolitan army was able to win the battle, taking Caldora himself as a prisoner (although he would later be freed). The dragon recalls that episode: the coat of arms with oblique stripes is that of Paolo di Sangro, while the dragon is an Aragonese symbol (St. George had been made the patron saint of Aragon as early as the 14th century), and the fact that in its claws it clutches upside-down Angevin lilies is meant to symbolize the fact that the territory of Civitacampomarano was now subject to the Aragonese crown.

A funerary cippus was, in ancient times, a square-shaped stele that was erected in the presence of a tomb: the top part was often decorated with a symbolic figure. In this case, the figure is a gorgon, an anguicrinite (i.e., snake-haired) monster whose gaze was capable of petrifying anyone who looked into its eyes. According to mythology, the gorgons were three sisters, Steno, Euryale and Medusa: the latter, of the three, was the only mortal, and in fact was defeated and killed by the hero Perseus. Gorgons have also been part of funerary symbolism since Etruscan times, since according to tradition they were the guardians of the threshold that separated the world of the living from the world of the dead and therefore repelled anyone who tried to cross it. The gorgon in the Venafro Archaeological Museum, from Roman times, was found in a burial ground just outside the town.

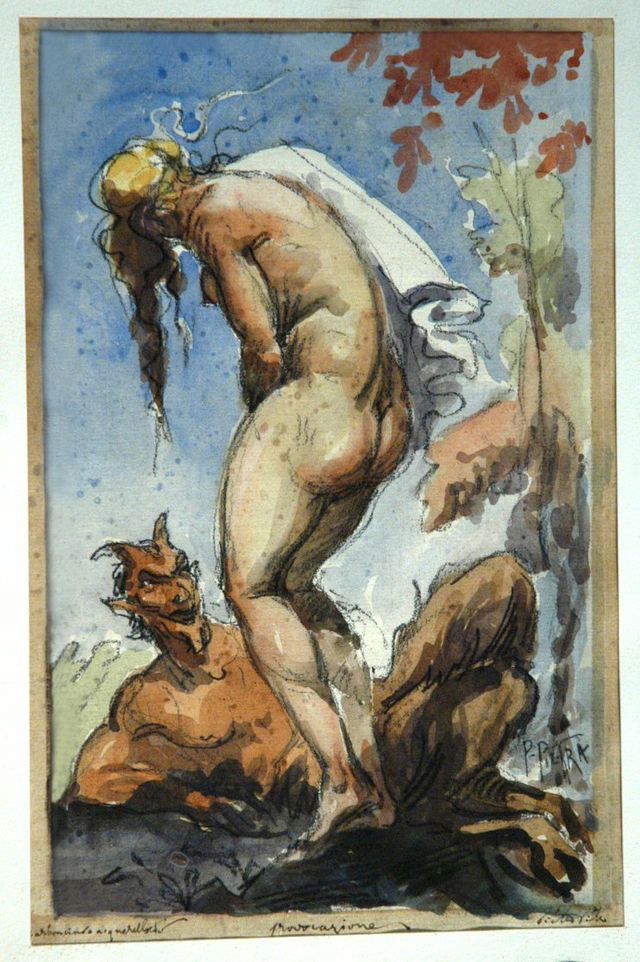

Active primarily as an etcher, Pietro Pietra (Bologna, 1885 - 1956) specialized mainly in depictions of animals in a style that drew on the aesthetics of late 16th-century painting. This allegory of Provocation is no exception, in which a naked young woman, seen from behind as she returns from a bath complete with a towel over her shoulder, is provoked by a reclining satyr who watches her disturbingly: in ancient mythology, in fact, satyrs were considered creatures with a strong sexual appetite and very instinctive. The work, kept at the Palazzo Pistilli Museum in Campobasso, was donated to the institute in 2014 by Campobasso collector Michele Praitano, who with his deed decided to leave the Molise capital’s institute a collection that was the result of 50 years of research. It was Praitano’s bequest that enabled the formation of the museum’s main nucleus, which opened on May 16, 2014.

The term “pyxis” was used in antiquity to refer to a small container, with a usually rounded body, that served to hold small objects. They could have been made of ivory, bone or terracotta. This one from the Samnite Museum in Campobasso, which dates from the Hellenistic period (it can be dated to the end of the 4th century B.C.) has the typical cup shape that rests on a foot: it was usually used to hold cosmetic items. Pyxisids not infrequently had a decorated lid: this one features a head of Pan, the god of the woods, whose iconography of a creature with a human body and goat’s feet began to spread in southern Italy toward the end of the 5th century BCE.

Hellenistic

HellenisticThe frescoes that decorate the main floor of Gambatesa Castle were commissioned by Vincenzo Di Capua, Duke of Termoli, from Donato da Copertino (16th-century news), who carried out the work, as an inscription we find in the very decoration states, in August 1550. It is one of the most interesting fresco cycles in the whole of Molise: the artist was trained in Roman circles (he looked in particular to Daniele da Volterra, Pellegrino Tibaldi and Francesco Salviati) and brought this culture to the Molise area. In the halls of the palace, Donato da Copertino brought to life episodes from mythology and ancient history with imposing figures and ringing tones. There are also fantastic animals in these frescoes: the pair of sphinxes in the Hall of Landscapes stands out. They are depicted, in keeping with tradition, facing each other, with the guardian function attributed to them in antiquity.

In Larino, near the amphitheater, the largest preserved monument of the Roman city (it dates back to 81 A.D., so it is contemporary with the Colosseum), there is now the Archaeological Park Roman Amphitheater - Villa Zappone, which also allows you to visit the remains of some of the buildings of Roman Larino. Near the amphitheater were baths: those in Larino were particularly luxurious, and had floors decorated with splendid mosaics. In one of them you can see some hippocampi, a fantastic animal with the legs of a horse and the tail of a fish. In the spa complexes of antiquity it was customary to decorate the floors with subjects from the sea world, a reminder of the waters in which the city’s inhabitants bathed.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Molise |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.