If there is a place where the sea is not just a geographic boundary, but a soul that has shaped its history and brings it to life, that place is the province of Livorno. Here, the sea is not just an element of the landscape, but an essential component of daily life, a protagonist of history and an engine of transformation that, over the centuries, has shaped the destiny of the communities that border it. From the city of Livorno, with its ancient port and multicultural roots, to the resorts of the Etruscan Coast and the majesty ofElba Island, the entire provincial territory has a special relationship with its sea. The sea has brought wealth and trade, but it has also marked periods of decline, wars and conquests. It has been the route through which merchants and navigators, artists and fishermen, conquerors and revolutionaries have passed. It has inspired generations of painters, writers and musicians, offering them an endless palette of colors and suggestions.

Today, the relationship between Livorno and its sea expresses itself in many forms: it is at the center of an economy based onindustry, port and tourism; it is an indispensable element of culture and tradition; it is the setting in which the everyday life of those who live along the coast takes place. But beyond the practical and concrete aspects, the sea is above all a symbol, a constant presence that accompanies those who inhabit these lands. It is the background of family stories, the protagonist of local legends, the boundary always open to new horizons. Telling about Livorno and its province without talking about the sea, then, would be impossible. It is a story that has its roots inEtruscan times and reaches to the present day, passing through the centuries with the unstoppable force of the waves that, tirelessly, continue to lap these shores.

The Gulf of Baratti is the southernmost area of the province. It is here, on the promontory overlooking the gulf, that the city of Populonia, the only major Etruscan center located on the sea, is located. This once powerful and prosperous settlement based its wealth on the working of iron from theisland of Elba. Even today, among the ruins of the ancient city and the necropolis scattered along the coastline, one can still breathe in the charm of a civilization that was able to exploit the sea for trade and its own economic expansion. The Baratti and Populonia Archaeological Park allows visitors to take a journey back in time to discover how the Etruscans prospered with the iron industry and maritime trade. The Etruscans’ penchant for maritime trade led them to establish strategic coastal settlements, the emporiums, which served as trading posts and facilitated interactions with other cultures. These emporiums were often located near navigable rivers or along crucial trade routes, allowing a continuous flow of goods and resources. But here in front, the waters of the gulf are also a reminder that the sea was Populonia’s great ally, but also the cause of its decline, when invasions and declining trade routes led to its abandonment.

These shores would flourish again later, however , thanks to Livorno’s role. A city born with the sea and for the sea. If today it is a city with a proud and cosmopolitan character, it owes it above all to its port, which has been one of the most strategic ports of call in the Mediterranean since the 16th century. The Medici, sensing its potential, developed it from the late 16th century onward, transforming what was once a small fishing village into a large merchant and multi-ethnic city. The “Free Port,” established in the 1690s, attracted merchants from all over Europe: Armenians, Jews, Greeks and Dutch found a hospitable land here, giving rise to an open and dynamic society. And the “Leghorn laws” enacted during the same period (in 1591 and 1593 to be exact) by Grand Duke Ferdinand I de’ Medici favored the city’s population and economic expansion.

Today, the port of Livorno is still a vital hub for the local and national economy. It is one of the main ports of call for commercial and passenger traffic in Italy, with daily connections to Sardinia, Corsica and Spain. The fast-growing cruise industry brings thousands of tourists each year from Livorno to the beauty of Tuscany, from Florence to Pisa. However, its origins are much older: it was 1421 when Livorno, then a small village, came under the control of the Republic of Florence. During this period, the Marzocco Tower was built, a symbol of the growing strategic importance of the port of call. However, it was in the 16th century, under the leadership of the Medici, that the port experienced significant expansion. Grand Duke Ferdinand I de’ Medici promoted the construction of the Darsena Vecchia, known today as the Molo Mediceo, turning Livorno into a free port and attracting merchants from all over the world. In the 19th century, further infrastructural developments consolidated Livorno’s position as a major maritime hub. In 1852, under the reign of Leopold II, the construction of a rectilinear seawall was begun to protect the port from mistral winds. Later, a grandiose curvilinear breakwater, known as the “Molo Novo,” was built to distinguish it from the earlier “Molo Vecchio” built during the Medici period. Currently, the port of Livorno is one of Italy’s main ports for cargo traffic (it is the third in Italy after Trieste and Genoa) and passenger traffic . To further support and upgrade its infrastructure, in July 2024, the Port of Livorno obtained a 90 million euro loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB). This investment aims to promote sustainable expansion of the port of call, strengthening its competitiveness internationally. The port also plays a key role in the cruise and passenger transport sector. In 2019, it welcomed more than 3.5 million passengers, confirming it as one of the main entry points for maritime tourism in Italy. Curiously, in terms of passengers, the port of Livorno is not the first in the province: the first (and third in Italy) is that of Piombino, which is very popular because it is the port of departure for theisland of Elba.

This island, the largest in the Tuscan Archipelago, has a history closely linked to iron mines exploited since Etruscan times, is known for Napoleon’s exile in 1814 and today is one of Italy’s most popular tourist destinations, thanks to its varied beaches, villages overlooking the water and the opportunity to practice water sports such as diving, sailing and windsurfing. The marine protected area of the Tuscan Archipelago National Park, established in 1996, ensures the protection of a unique ecosystem where dolphins and sea turtles swim undisturbed.

Of course, the sea is also an essential economic resource for the province. Beach tourism is one of the driving sectors, with resorts such as Cecina, San Vincenzo, Donoratico, and Bibbona filling up each summer with tourists seeking equipped beaches and clear waters. The Etruscan Coast offers an alternation of golden sandy shores, wild cliffs and hidden coves, attracting both families and nature lovers. No less important is the role of fishing and recreational boating. Fishing-related activities, although scaled down from the past, continue to be an identity component of the city, as evidenced by the lively atmosphere of Livorno’s Fish Market and the culinary tradition associated with cacciucco.

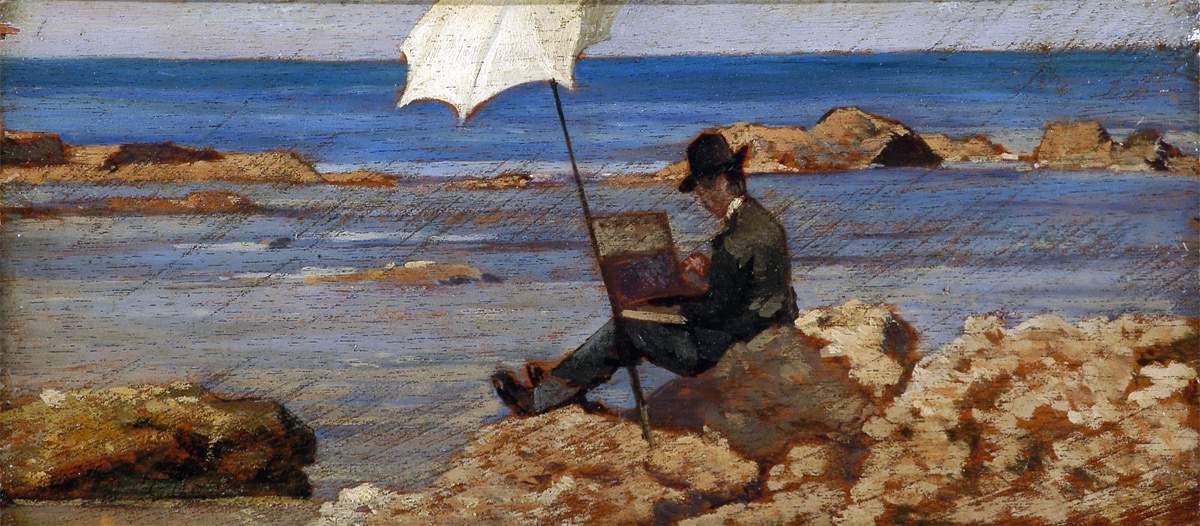

If the sea has shaped Livorno’s history and economy, it has played an equally fundamental role in its artistic identity. The Macchiaioli, the famous nineteenth-century painting current, found their source of inspiration on Livorno’s shores. Artists such as Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega and Telemaco Signorinipainted the beaches, harbors and daily life of fishermen with quick, luminous brushstrokes. The coasts of the province, from Castiglioncello (where the first leading critic of the Macchiaioli group, Diego Martelli, had a villa to which he invited his painter friends on several occasions) to Rosignano, were their open-air workshop. Even today, walking near the cliffs of Castiglioncello or among the farmhouses of the Livorno countryside, one can recognize that golden light that made the Macchiaioli canvases unmistakable. The Macchiaioli movement was born in the second half of the 19th century in Tuscany, in opposition to academic painting. These artists, including Cristiano Banti, Silvestro Lega, Telemaco Signorini and the Leghorn-born Giovanni Fattori, developed an innovative technique based on the representation of light and color through “macchia,” or quick, decisive brushstrokes that capture the immediacy of reality.

Livorno, with its sea, cliffs and beaches, soon became a privileged stage for this new way of painting. The bright atmospheres of the Tyrrhenian coast, the clear sky reflecting on the waters, the fishermen’s boats, the harbor crowded with merchants and sailors-all offered perfect cues for artists seeking to capture life in its purest essence.

Among the Macchiaioli, Giovanni Fattori is undoubtedly the artist who was best able to express the beauty of Livorno’s seascape. “I love the sea because I was born in a seaside town,” he had to say, and the relationship between Giovanni Fattori and the sea was always inseparable. Born in Livorno in 1825, Fattori spent much of his life observing and painting the sea in his city. His works often depict scenes of daily life on the beaches or along the coast: soldiers on horseback, bathers, sailors at work, peasants resting near the shore. So many of his works testify to his deep connection with the Livorno coastline, and the sea, in his canvases, is never a static or decorative element, but an integral part of the scene, rendered with quick, light-filled brushstrokes.

And if Livorno is the center of the artistic tradition linked to the sea, Castiglioncello is his chosen refuge. This small coastal village, with its sheer cliffs and wild vegetation, became a point of reference for the Macchiaioli, who chose it as a place of meeting and inspiration. Critic and collector Diego Martelli, as anticipated, hosted many painters of the time here, giving rise to a true artistic community, which art historian Dario Durbè would rename as the “School of Castiglioncello.” The Macchiaioli painted en plein air, in the open air, trying to capture the variations of light on the sea and the chromatic nuances of the coastal landscape. The influence of the Macchiaioli continued to live on in Leghorn art even after the movement ended. Painters such as Plinio Nomellini, Llewelyn Lloyd, Renato Natali, Gino Romiti, Giovanni Lomi, Benvenuto Benvenuti, Ulvi Liegi, Carlo Domenici, Cafiero Filippelli, Renuccio Renucci, Guglielmo Micheli, Giovanni March, Gastone Razzaguta and several others, all originally from Livorno or living here for most of their lives, carried on the tradition of landscape painting, reinterpreting the Livorno sea in a Symbolist, Divisionist or post-Macchiaioli key. Many of them gave birth to, or would participate in, the Gruppo Labronico, an artistic association born in 1920 and still active today thanks to the artists who pose as heirs to that tradition (such as Massimo Lomi, Stefano Bottosso, Fiorenzo Luperini and others). Today, walking along the ditches or on the beaches of the Livorno province, one can still perceive that special bond between artists and the sea: a bond made of light, vibrant colors, and life flowing through the waves.

Whether it is a busy port, a lonely reef or a crowded beach, the sea continues to be the thread that binds past and present in the province of Livorno. It is an economic engine, a source of artistic inspiration, a witness to the millennial history of these lands. But, above all, it is part of the culture of those who live here, marking the character and spirit of a land that always looks toward the horizon, with the salty wind blowing over it and the knowledge that the sea is not just a landscape.

|

| Livorno and the sea, a thousand-year history that begins with the Etruscans |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.