The term “Macchiaioli” refers to the large group of Tuscan painters who, shortly after the second half of the 19th century, proposed a completely new art, a break with the historical and academic painting that dominated the taste of the time in Italy. Initially the group did not have a term to define themselves: However, they took to calling themselves “macchiaioli” after an anonymous reviewer of the daily newspaper La Gazzetta del Popolo (although it is highly likely that behind the pseudonym “Luigi” by which he signed himself was the philologist Giuseppe Rigutini), in an article published on November 3, 1862, used the term in a derogatory sense to refer to the artists who had exhibited their works at an exhibition of the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti in Turin the previous year. “Will the reader tell me, if he is not an artist, but what are these Macchiaioli?” the journalist wondered. “They are young artists and some of whom one would be wrong to deny a strong intellect, but who set out to reform art, starting from the principle that the effect is everything [...] and that in the veins and varied stains of the wood they claim to recognize a little head, a hominin, a little horse? And the little head, the hominin, the little horse is in fact there in those stains.... you just have to imagine it! So it is of the details in the paintings of the Macchiaioli. In the heads of their figures. But you look for the nose, the mouth, the eyes, and the other parts: you see there spots without form [...]. That the effect must be there, who denies it? But that the effect should kill the drawing, fin the form, that is too much.”

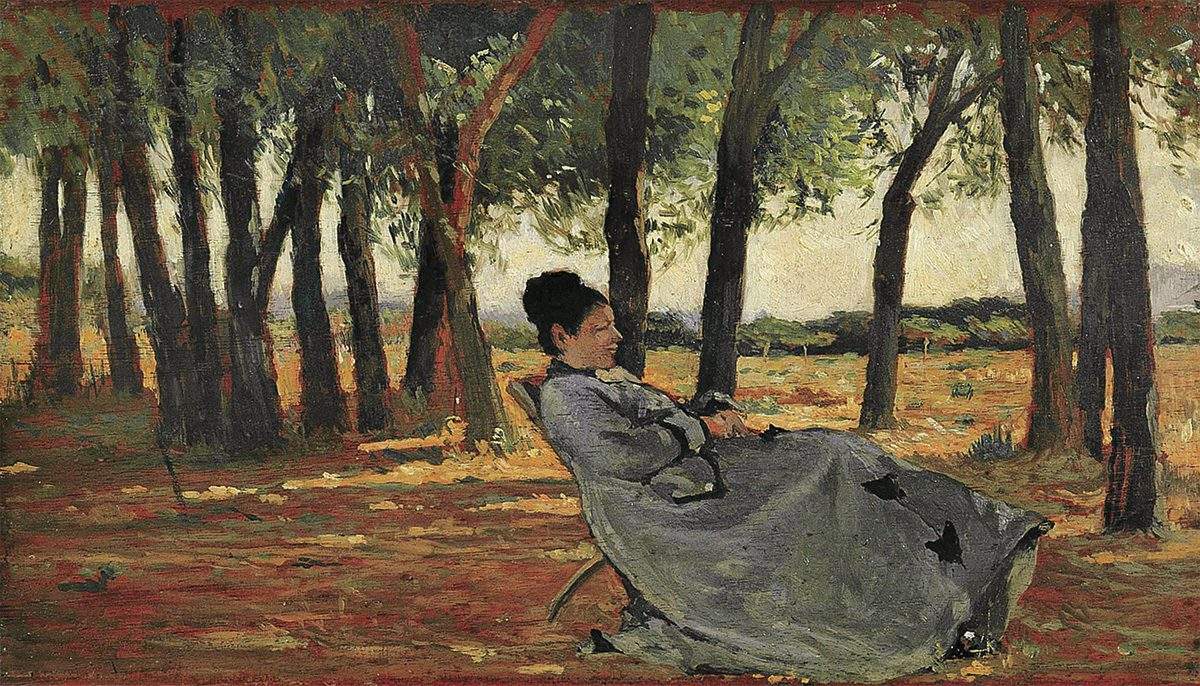

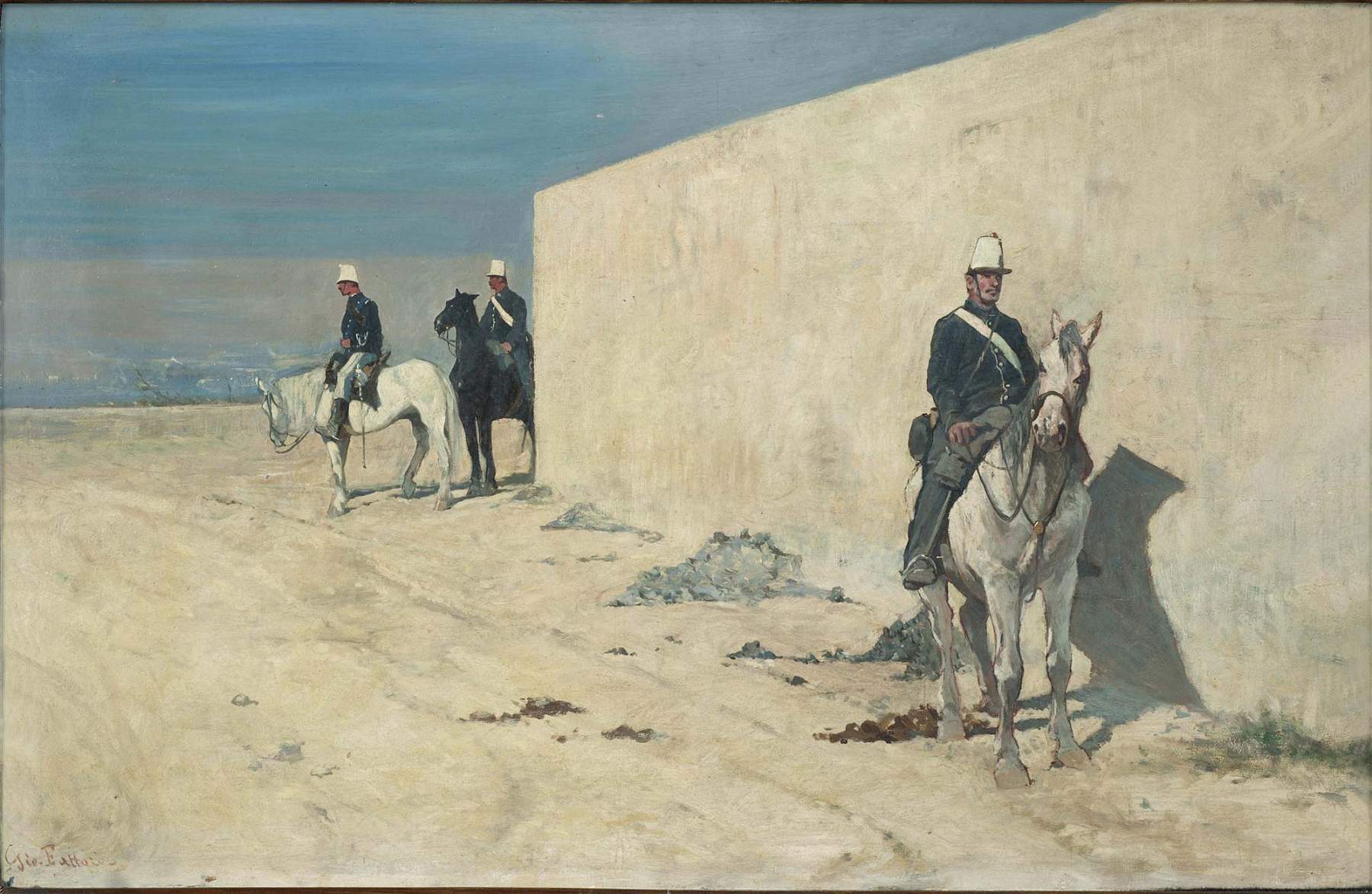

The response of one of the leading Macchiaioli, painter as well as theoretician of the group (along with, in this role, Adriano Cecioni and , later, critic Diego Martelli), Telemaco Signorini (Florence, 1835 - 1901), was not long in coming: “the macchia,” he would always reply in print, “was nothing but a too precise mode of chiaroscuro, and an effect of the necessity in which the artists of that time found themselves to emancipate themselves from the capital defect of the old school, which, to an excessive transparency of bodies, sagrified the solidity and relief of its paintings.” The Macchiaioli, who never had a painter who could be considered the “father” of the movement, despite the fact that some, such as Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega and Signorini himself, reached more extreme than the others and are considered the most successful ones, were essentially independent artists, who in a sort of movement of rebellion against the historical and mythological painting of Romantic matrix wanted to propose a new, more spontaneous art, based on attention to reality and everyday life, with a style capable of conveying with immediacy the subjects that the Macchiaioli tackled.

“The Macchiaioli,” wrote art historian Francesca Dini, “are one of the most original avant-gardes in Europe in the second half of the 19th century. [...] They are the most highly poetic expression of Italy born of the heroic Risorgimento processes of national unification. And in this their uniqueness can be said to be absolute and unrelatable to other pictorial contexts and movements of the time. In addition, the profound perception that these great artists had of their time raises their poetic sentiment to values of universality as only great art knows how to do, captivating with the formal and poetic fullness of extraordinary masterpieces indelibly imprinted in our collective memory.”

The history of the Macchiaioli began at the Caffè Michelangelo in Florence, an establishment near the cathedral where, beginning in the 1850s, a group of Tuscan artists, namely Cristiano Banti (Santa Croce sull’Arno, 1824 - Montemurlo, 1904), Odoardo Borrani (Pisa, 1833 - Florence, 1905), Adriano Cecioni (Fontebuona, 1836 - Florence, 1886), Serafino De Tivoli (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1892), Raffaello Sernesi (Florence, 1838 - Bolzano, 1866), Telemaco Signorini and later the Livorno-born Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908), and which would later be enriched by other personalities from outside the region, including the Veneto-born Vincenzo Cabianca (Verona, 1827 - Rome, 1902), Emilian Giovanni Boldini (Ferrara, 1842 - Paris, 1931), Romagna’s Silvestro Lega (Modigliana, 1826 - Florence, 1895), Marche’s Vito D’Ancona (Pesaro, 1825 - Florence, 1884), and Campania’s Giuseppe Abbati (Naples, 1836 - Florence, 1868). Initially, the Macchiaioli called themselves “progressives” and their aim was to challenge the academy, especially starting in 1855, when Saverio Altamura (Foggia, 1822 - Naples, 1897) and De Tivoli went to Paris to visit the Exposition Universelle and learned about modern French landscape painting. The Macchiaioli (who, as mentioned above, would not be so called until 1862, and would immediately make that derogatory nickname their own) immediately came to the fore in a polemical sense, as is often the case when a group of young artists intends to subvert the rules.

It was on May 23, 1857 when the then director of the Florentine Promotrice, Augusto Casamorata, rejected two paintings by Telemaco Signorini, deeming the chiaroscuro that characterized them excessive, and thus effectively rejecting the new poetics of “macchia”: a debate ensued in which several artists and critics of the time would participate for several years. The most serious controversy occurred, however, in 1861, when a group of artists belonging to the movement, namely Giuseppe Abbati, Francesco Saverio Altamura, Luigi Bechi and Vito D’Ancona criticized the commission of theNational Exhibition in Florence for its choices, going so far as to refuse the gold medal that the Exhibition had given to Vito d’Ancona (refusing the medal was a way of questioning the authority of the commission). The Macchiaioli believed that “the fine arts are not a code that is learned by articles,” like a legal text in short: it meant that the artist, once he has received the first rudiments, should be left free to follow his own path and to follow the models that best suit his style, be they nature or contemporary artists (the academies of the time insisted instead on the example of the artists of the past).

The Macchiaioli revolution started “from within,” so to speak: their works, too, initially favored historical subject matter, but with an entirely new outlook, borrowed from the French painter Paul Delaroche, who, instead of rhetorically celebrating the great events of the past, focused on the seemingly most insignificant details of a historical fact, yet recounted them truthfully and with pathos. Soon, however, even history painting began to get too tight for the “progressives,” who therefore decided, following the example of what artists such as Serafino De Tivoli and Nino Costa were doing, to concentrate on landscape painting. And each tried to do so independently, traveling along Italy or staying in Tuscany but never ceasing to update: among the artists who loved to travel most often was Telemaco Signorini, who began his own experiments on macchia in 1859 on the Ligurian Riviera, in the area of La Spezia (the works executed in this year can be considered the first Macchiaioli works in their own right), while Giovanni Fattori, on the other hand, was much more sedentary, but in the same year he got to know Nino Costa and spent several times with him, who was staying in Livorno. His acquaintance with Nino Costa enabled him to look at landscape painting from a completely new perspective: landscape painting would no longer seek to be pleasing (as in neoclassical painting), or would no longer try to capture the majesty of nature as was the case in Romantic painting. On the contrary, the Macchiaioli focused even on seemingly less interesting landscapes (a glimpse of a beach, an alley in a city, a country lane), but capable of conveying a feeling to the viewer, thus in advance of the landscape-state-of-mind quests that would characterize European painting a few years later. It is significant to recall that De Tivoli and Costa were admirers of Corot’s painting and of the painters of the Barbizon School, which had radically renewed the European landscape: it was they who brought the new ideas to Italy and converted to landscape painting even painters, such as Vincenzo Cabianca, who until then had devoted themselves mostly to figure painting.

An important juncture in the history of the Macchiaioli is given by 1859, the year of the Second War of Independence: many artists participate firsthand in the fighting, and the opportunity to observe war events up close becomes a way of renewing battle painting, which is emptied of all rhetorical intent (in fact, the artists prefer to emphasize the valor of the soldiers by focusing on the harshness of their sacrifice and the truth of their feelings rather than on the heroism of their deeds). Instead, the exhibition at the Promotrice in Turin that earned the Macchiaioli the name by which they would later be universally known dates back to 1861. Here, the group’s painters exhibited their most daring experiments, attracting criticism but also praise, so much so that the exhibition was considered a victory, and from then on the artists became increasingly aware of the goodness of their project. Thus dates from the 1960s a more insistent focus on the landscape, so much so that many will choose places to retreat to: some would thus animate the so-called "School of Castiglioncello, " named after the locality near Livorno where the critic Diego Martelli (Florence, 1839 - 1896), very young but soon to become the group’s leading critic(read more about him here), had inherited from his family a large estate between sea and countryside where he often hosted the group’s artists (Fattori, for example, was a frequent guest), and the “Scuola di Piagentina”, named after the town near Florence that was instead favored by Silvestro Lega and where Sernesi and Abbati worked, in addition to the Romagnolo.

The Caffè Michelangelo experience ended in 1866 when the café closed: the group then gathered around the journal Gazzettino delle arti del disegno, founded and directed by Diego Martelli, who, through the journal, wanted to create a “virtual” meeting place for the group and at the same time to spread the ideas of the Macchiaioli (it was, for example, also thanks to the Gazzettino that the inspiration of Giovanni Boldini, who in his youthful years was close to the Macchiaioli espousing their ideas, came to the attention of the environment), even for the mere purpose of debate. The movement would begin to lose bite in the 1970s, with the disappearance of some early Macchiaioli (such as Sernesi and Abbati), with some, such as Cristiano Banti, being introduced into “official” circles (in 1870, for example, Banti was a member of the jury of the National Exhibition in Parma and later, in the 1980s, would become a lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence), and with the transfer of several others. Cabianca, for example, moved to Parma in 1863 and then, in 1870, moved permanently to Rome, while others such as De Tivoli, Boldini, and D’Ancona moved to Paris moved by a desire to work in the world art capital of the time. Only a few remained in Florence: Signorini, Fattori (who, however, often returned to his native Livorno), Borrani and Cecioni who were the masters of the artists of the new generation, led by Francesco Gioli (San Frediano a Settimo, 1846 - Florence, 1922) who had made his debut in 1868 at the Società d’Incoraggiamento in Florence and since 1870 had approached Fattori and Signorini, as well as Diego Martelli whose guest he was often in Castiglioncello. However, the Macchiaioli continued to paint and experiment throughout their lives: success was definitively established in the 1890s when they came to exhibit at the first Venice Biennale.

The macchia, wrote Telemaco Signorini, “was nothing more than a too severed mode of chiaroscuro.” The term “macchia painting” refers to a synthetic pictorial drafting, through which the painter renders the elements on the canvas with uniform color backgrounds (the “spots”) that generally avoid describing details (in fact, faces without connotations are often noted in the paintings of the Macchiaioli) and that make objects emerge through strong contrasts of light and shadow and vigorous chiaroscuro effects. An interesting definition of “macchia” was given by the scholar Vittorio Imbriani, who defined macchia as “an agreement of tones, that is, of shadow and light, apt to arouse in the soul any feeling by exalting the imagination to the point of productivity,” and reiterating that macchia is “the portrait of the distant first impression of an object or scene [...]. This indeterminate, distant first impression, which the painter affirms in the stain, is succeeded by another distinct, minute, detailed one. The execution, the finishing of the painting is nothing more than a getting closer and closer to the object, than unraveling and fixing what has passed over our eyes like a gleam.”

Theoriginality of the Macchiaioli lies above all in two elements of their art: the technical novelty just described, and the intent to free painting from a narrative (the aesthetic, rather than the narrative, is what most interested the Macchiaioli). This, then, explains why they focus so much on nature, which is analyzed in all its expressions in order to bring out, through the “macchia,” its most interesting aesthetic qualities. For the Macchiaioli, the study from life, en plein air, borrowed from the coeval French landscape painting, also counted a lot: in fact, the Macchiaioli often went to the countryside or to the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea to make sketches from life. The cliffs in front of Castiglioncello or the rural atmospheres of Piagentina near Florence (a “humble and modest” countryside, Signorini described it, “flat with vegetable gardens, orchards and still a few houses; the famous hills of Fiesole, San Miniato and Arcetri can be seen only in the distance. Here just outside the walls, coming out of Porta alla Croce, [...] there lived peasants occupied in the cultivation of vegetables, and a few bourgeois families, not aristocrats, who lived in small villas, farmhouses, quite different from the stately country dwellings...”), thus became familiar places where one could exercise from life all the potentialities of the macchia. Reality is the Macchiaioli’s privileged field of investigation: the effects that light casts on a wall in the countryside, the effect of the sun on the waves of the sea, a forest in the distance, a farmhouse against the light, a line of mountains are perhaps the most genuine protagonists of Macchiaioli art, not least because the painters of the group saw in the landscape a kind of equivalent of their sensibility, anticipating in this way the research on the landscape-state of mind.

“According to the precepts of the naturalist philosophy,” wrote art historian Tiziano Panconi, “art had to strive to make a transcription of the real datum as objective as possible, carrying out that necessary process of analysis and verification that had been the exclusive prerogative of science up to that time. [...] The Tuscan artists of this new age, no longer able to proceed by further descriptive subtraction - a path whose ascending parabola is witnessed by paintings of the 1960s such as Sernesi’s Tetti al sole or Cabianca’s Il muro bianco or, just to mention another fundamental work, Palmieri’s La rotonda - recovered those narrative connotations that qualified, in effect and across the board, all the art of the period. As had been the case in the regional painting of the past, from Giotto to Leonardo onward, and evidently resenting a tradition so deeply rooted in the collective cultural heritage, the advances of contemporary thought had been brought back to the limpid immediacy of the austere closed forms, where the excellence of the drawing imprinted the plumb cadences of the simple clothes of the peasant women, now assumed to be true icons of the centuries-old rural civilization.”

Precisely because of their revolutionary and reformatory intentions, because of their continuous striving for experimentation, because of the very way in which the Macchiaioli artists had renewed painting, as well as because of the common naturalist substratum they drew on, the Macchiaioli are often considered anticipators of the Impressionists, if not of the Italian “Impressionists,” although the comparison could be misleading, since several differences separate the Macchiaioli from the Impressionists. The Macchiaioli, despite their many affinities with the Impressionists (their synthetic painting, their interest in agrarian or, conversely, bourgeois subjects, their reformist intent, their anti-academism, their name born in a derogatory sense), were meanwhile more attached to tradition (they did not, for example, reject drawing), and they kept faithful to the perspective patterns typical of Italian painting, something that was not in the chords of the Impressionists (“However sonorous, vivid and masterfully tuned,” Giulio Carlo Argan wrote about the relationship between space and color in the art of the Macchiaioli, “the chromatic and luminous notes do not make space but fill a given space; they do not move along space by imposing their rhythm on it; they move along the obligatory paths of a given and unchanging space. And since, as they move, they appear as changeable with respect to a reality that does not change, their presence is episodic: if, by hypothesis, the perspective armature disappeared, the chromatic steadfastness would dissolve into colored vapors.”) This is also why, comparing Macchiaioli and Impressionists, the former might seem less daring than the latter. Again, the light of the Impressionists is much more elusive than that of the Macchiaioli, who anchored in more solid and structured patterns of construction appear less vibrant than their French colleagues.

The main “temple” of the Macchiaioli is the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Palazzo Pitti in Florence, where several collections have converged that include masterpieces by all the Macchiaioli, including the legacy of Diego Martelli (an entire room displays paintings that were in the collection of the group’s leading critic). Another key museum for learning about the Macchiaioli is the Museo Civico “Giovanni Fattori” in Livorno, where the main existing nucleus of works by Giovanni Fattori is preserved: many of his major masterpieces are on display here along with works by other Macchiaioli painters of the first and second generation.

Other museums include in their itineraries works by artists who participated in the renewal of macchia painting: These include the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro in Venice, the Raccolte Frugone in Genoa, the Galleria Ricci Oddi in Piacenza, the Gallerie d’Italy, the Matteucci Institute in Viareggio, the Pinacoteca “Silvestro Lega” in Modigliana, and the Galleria d’Arte Moderna “Achille Forti” in Verona.

A great many works by Macchiaioli painters (including many masterpieces) are to be found in private collections: the little interest that public collections have long had for museums (in fact, almost all the important nuclei of Macchiaioli works preserved in museums originate from private collecting, or are the result of donations or legacies rather than public acquisitions) has favored the private market. Finally, since, after decades of little interest, in recent times (at least since the early 2000s) the Macchiaioli have become a phenomenon of success with the public, it is not uncommon for exhibitions to be organized either on the movement, even at the same time (as at the end of 2022 with exhibitions on the Macchiaioli in Pisa and Trieste), or on individual artists (Giovanni Fattori is the one who has enjoyed the most consistent exhibition fortune so far).

|

| The Macchiaioli: history, style and origin of the group |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.