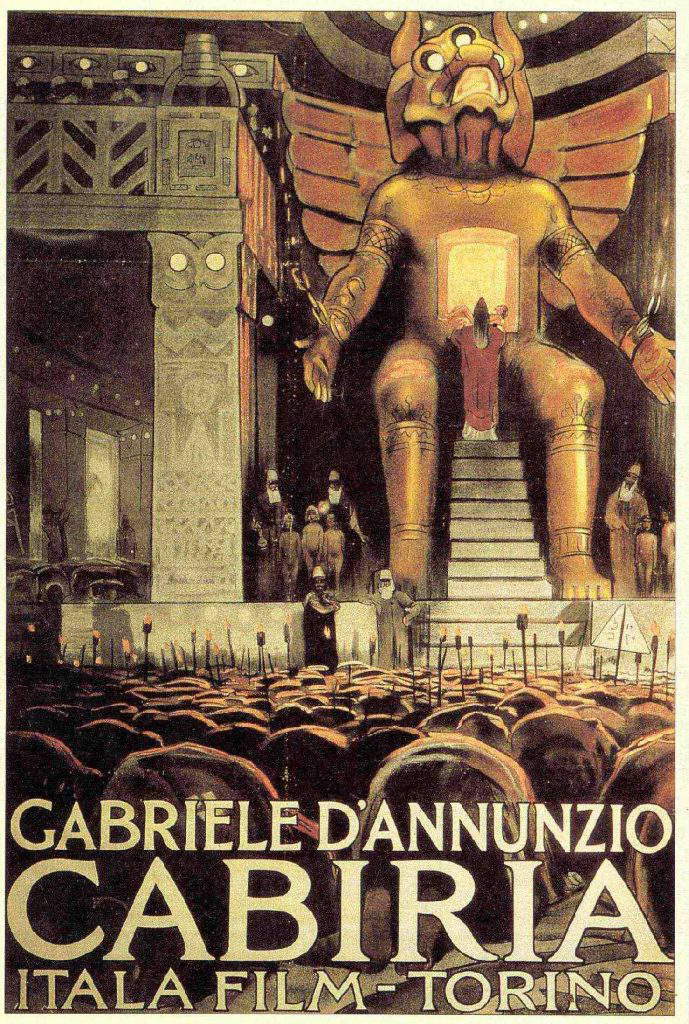

“Hate me, voracious creator who all begets and pines, insatiable hunger, hate me!” “Behold thee the purest flesh! Behold thee the mildest blood! Karthada gives thee thy flower.” “Consume the sacrifice thyself in thy jaws of flame, O father and mother, O thou god and goddess! O father and mother, O thou father and son, O thou god and goddess! Voracious creator! Burning hunger, roaring....” And there appears the great temple of the god Moloch, where before a crowd of worshippers holding burning flames in their hands the sacrifice is performed: the pontiff Karthalo throws children into the belly of the monumental statue of the god Moloch, guardian of the temple, as sacrificial victims, to immolate them to the furious creator, from whose mouth a blaze of smoke comes out. This is one of the best known and most dramatic scenes in what is considered one of the most famous films of Italian silent cinema, Cabiria, directed in 1914 by Giovanni Pastrone and scripted by Gabriele d’Annunzio. Today, a copy of that statue, which was nothing more than a bronze furnace in the shape of a winged monster with three eyes, large ears, a huge open mouth and devil horns, guards, like an eerie janitor, the large Temple Hall of Turin’s National Museum of Cinema, the centerpiece of the museum housed in the Mole Antonelliana.

The statue of the god Moloch used for Pastrone’s kolossal, filmed in Itala Film’s factories along the Dora Riparia, and whose title was devised by D’Annunzio himself, who was involved in the film by Pastrone himself, who spoke to him of a “project of good profit and minimal disturbance” (Cabiria, a “name evocative of volcanic demons” as the poet wrote, is precisely one of the little girls chosen as a sacrificial victim to Moloch), was inspired, as was the entire set design, by the art of Mesopotamian, Phoenician, Greek and Egyptian antiquity, given also the presence in the city of the Egyptian Museum, which surely may have provided important insights for set designers Luigi Romano Borgnetto and Camillo Innocenti. It is hard not to think, for example, of the representations of Pazuzu, the demon of the winds from Babylonian mythology, the bringer of storms, depicted as a winged being with a head resembling that of a dog, similar to that of Moloch in Cabiria. Inspiration had to come from literature as well: in Gustave Flaubert’s novel Salammbô, there is mention of a Moloch described as a bronze idol with “boundless arms” and “long wings” that “descended to plunge their tips into the flames,” with its feet resting on a “round stone.” Also in Emilio Salgari’s novel Carthage in Flames , “Molok” is a bronze idol devouring virgins and children in the flames.

Frame from the

Frame from the Photogram from the

Photogram from the

It almost seems as if the colossus will come to life at any moment in the Temple Hall, where Moloch is seated on a kind of throne and chained by the wrists to the wall. It is difficult to relax with such a presence overseeing the comfortable red chaise lounges placed in the center of the room on which visitors are invited to lie down to enjoy the films on the program (for this is indeed a movie theater inside a museum). From here, still under the eye of the statue, visitors access the Helical Ramp that rises, unrolling like a movie film, toward the Mole’s dome: having reached the top, one can admire the Temple Hall from above, from another perspective.

But why did the central hall of the National Cinema Museum decide to devote so much space to the fearsome Moloch? The institution has often mentioned that Cabiria is one of the icons of Italian cinema, and it has gone to great lengths to preserve its memory: currently, the National Cinema Museum has the world’s largest collection of objects and documents on the film. In 2001, the museum acquired the original scripts, contracts, letters between D’Annunzio and Pastrone, and documents from the Pastrone Fund, after which in 2004 it began a film restoration commissioned from Prestech Film Laboratories in London, which was completed in 2006: it covered both the 1914 silent version and the 1931 sound version, and the restoration of the 1914 version premiered during the Turin Olympics, after which it was taken on an eight-stage world tour. What’s more, because it was filmed in Piedmont, it is a film deeply connected to the region.

Visiting the Cinema Museum of Turin, founded by Maria Adriana Prolo as a place intended to collect and accumulate film machines and materials that make up the museum’s original heritage (however, it is since 1995 that the museum has officially been housed in the Mole Antonelliana), thus allows one to take a profound journey also to the heart of equally unforgettable monuments: the great films of Italian cinema such as Cabiria.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.