Bologna, September 9, 1934. On the field of the Stadio Littoriale, as today’s Stadio Renato Dall’Ara was then called, the return final of the Mitropa Cup was being played. Which did not have the formula devised in the 1980s (i.e., a competition reserved for the winners of the B leagues of the various participating nations): no, in the 1930s it was the most prestigious international club competition. Because the strongest teams from the Central European football federations take part in the tournament. In the heyday of Danube soccer. Hungary, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Italy competed to the tune of goals in heartfelt matches in which the crowd, which flocked in large numbers, also played its part. Indeed: in the 1932 edition, it had been decisive, as public intemperance in the semifinal between Slavia Prague and Juventus caused both teams to be disqualified, guaranteeing the first Italian victory in the competition for Bologna, which qualified for the final and thus found itself the winner without even taking the field. Now, however, things are different: Bologna, in its second participation in the tournament, must faceAdmira from Vienna. After the glorious Rapid, which Bologna got rid of in the quarterfinals thanks to a resounding 6-1 thrashing at Littoriale, they are the most titled team in the Austrian league, and they are on the strength of a 3-2 win in the first leg, in a comeback, on their home field. Bologna plays with the support of an overflowing stadium, and in the entire edition has not lost a single match at home: it therefore starts with the favor of prediction. The Felsinei took the lead through Maini, but after ten minutes they were reached by a penalty kick taken by captain Adolf Vogl on which goalkeeper Mario Gianni, known as “the magic cat,” could do nothing. It is, however, a matter of seconds: after a minute Bologna takes the lead again with a goal by bomber Carlo Reguzzoni. From here on it is a rampage by the home team: two more goals by Reguzzoni and a goal by Fedullo set the score at 5-1. For Bologna, it is a triumph.

Echoes of the exploits of the “squadron that makes the world tremble,” a nickname Bologna soon began to earn, reached a then student at theAcademy of Fine Arts in Carrara, 22-year-old Ugo Guidi (Montiscendi di Pietrasanta, 1912 - Vittoria Apuana, 1977). The young sculptor is a Bologna fan: perhaps precisely because at the time the team had begun to reap one success after another and had thus earned the sympathy of many fans even outside Emilia. Therefore, the theme of sport cannot be absent from the production of Ugo Guidi, who was a great fan of sports: in 1934 he participated in the Littoriali di Cultura e Arte (in order to continue his studies, the artist had to join the GUF, the Gruppi Universitari Fascisti, associations that would, however, end up “producing” legions of anti-fascists, starting with Pasolini and Ingrao) with a relief depicting some swimmers. However, the sculptor is at his first artistic experiences, and the theme of sport will return to play a very prominent role in his art from the 1960s onward, a period from which Ugo Guidi’s production abounds with figures of soccer players, such as the 1963 Goalkeeper. This is a sculpture in Versilia tufa that offers us a rather intense synthesis of the salient features of Ugo Guidi’s art of this period (because his research is a continuous evolution): a kind of realism that looks to ancient, even very ancient art (starting with Etruscan art) and that updates itself on abstractionist tendencies to capture the figure in its essentiality. In this case, a goalkeeper who becomes one with the ball he saves. For it is as if goalkeeper and ball are one entity. The goalkeeper saves the result only when he has the ball firmly in his hands. The ball, in the goalkeeper’s secure grasp, becomes harmless and, indeed, can turn into a serious threat to the opposing team, because amazing goal-scoring actions can start from the goalkeeper. This is how this sculpture should be read, which, in 1969, at the request of the municipal administration of Forte dei Marmi, became a monument that can still be admired today in front of the stadium in the city of Versilia.

|

| Ugo Guidi, Goalkeeper (1963; tuff, 37 x 44 x 18 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Museo Ugo Guidi) |

|

| Ugo Guidi, Goalkeeper (1969; travertine; Forte dei Marmi, Stadio Comunale) |

What interests Ugo Guidi is to highlight the strength, the confidence, the energy of soccer players. This is what transpires in another of his works on the theme of soccer, made in terracotta in 1972, and known simply as Football Match. It is a relief: the protagonists this time are three, namely an attacker who unleashes a powerful shot, the defender who tries to stop his rival, and the goalkeeper who has the last word and prevents the ball from entering the net. Critic Marzio Dall’Acqua, in the introduction to a catalog of Ugo Guidi’s works published in 1997, wrote that the sculptor “loves the lone, solitary figure, not out of a heroic exaltation, which by now it is clear is foreign to his world, but for an existential concentration,” and asserted that Guidi’s figures could recall, in that they are “isolated, alone, in their effort,” Umberto Saba’s celebrated defeated goalkeeper (“The goalkeeper fallen to the defense / last vain, against the ground hides / his face”). The goalkeeper, in this Partita di calcio, is depicted together with two other players, but it is he, still, who is the decisive protagonist in the fate of the game (although here he is more reminiscent of Umberto Saba’s “other” goalkeeper, the one whose “joy somersaults, / makes kisses that he sends from afar”), and it is true that Ugo Guidi is not interested in exalting a champion. His footballers are never individually connoted. We do not know what jersey they are wearing, their expressions are often undefined, and always delineated with the same essentiality that connotes most of Ugo Guidi’s works: solid, compact, almost abstract forms, with some hints even of the futurism whose fascination Ugo Guidi has often shown to feel (the combination of the goalkeeper’s right leg and the diagonal lines starting from the striker’s foot suggest the power of the shot and the movement, the excitement of this phase of the game). Because Ugo Guidi intends to get to the root of the values of sport: commitment, sweat, toil, fair play.

|

| Ugo Guidi, Soccer Match (1972; terracotta, 30 x 44 x 6 cm; Forte dei Marmi, Museo Ugo Guidi) |

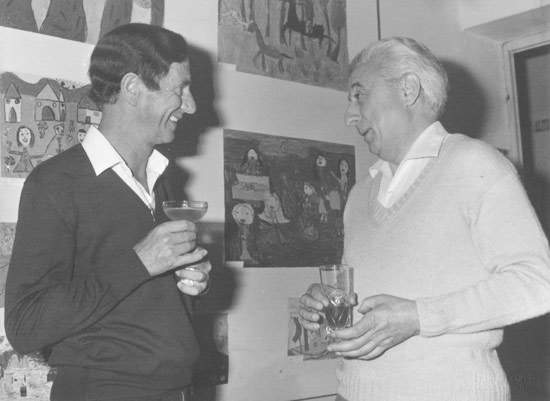

Universal values that unmistakably transpire from one of Ugo Guidi’s latest works on the theme of soccer. This is a prestigious work, one of the most important public commissions the artist received during his career. In fact, the artist is commissioned by the FIGC, the Italian Football Federation, to execute a monument for the Federal Technical Center in Coverciano, where the national soccer teams train. Ugo Guidi is an extremely shy person, but in his house-atelier in Vittoria Apuana, a hamlet of Forte dei Marmi, every summer he meets well-known artists and literati (some names: Alfonso Gatto, Achille Funi, Ottone Rosai, Piero Santi, Antonio Bueno, Ernesto Treccani, but the list is very long). This improvised circle is sometimes frequented by Artemio Franchi (Florence, 1922 - Siena, 1983), a sports executive who between 1967 and 1976 held the post of president of the FIGC, then left for a couple of years due to his concurrent commitment as president of UEFA, the association of European soccer federations. And subsequently a rather controversial figure. Ugo Guidi met him in the early 1970s. And the commission for the monument to be dedicated to Coverciano dates back to 1972, the year when the first drawings and sketches were made.

|

| Ugo Guidi (left) with Artemio Franchi |

The most famous of the latter is now in Pietrasanta, at the Museo dei Bozzetti. It is in plaster, half a meter high, and the artist executed it in his studio-atelier. It is still a study, but the idea is quite similar to what will later be the actual monumental translation in travertine. The protagonists are two soccer players, as yet uncontoured, wearing no particular jerseys. They are united in a grip: it is not clear whether it is a hug or a clash during the game. What is certain is that the ball is in front of them (it is especially noticeable in the travertine monument) and that the interpretation of the scene is up to the sensitivity of the observer, who can autonomously decide whether the gesture in front of him carries meanings of unity and brotherhood as values that soccer should embody at every latitude (sport, after all, is meant to unite), or whether what he is witnessing is the competitive charge of the encounter. It seems that, in short, Ugo Guidi wanted to portray, in a single moment and with his typical “essential poetic language, made up of delineated and sharp volumes that inhabit space and create the figure by subtraction,” as Alessandra Frosini writes, everything that soccer, and sport in general, represents. Sport is struggle, it is contention, it is sacrifice to achieve victory and to overcome each contender. But every sportsman must not forget values such as respect for the opponent, loyalty to one’s teammates, fairness, and the spirit of togetherness: a set of values not coincidentally summarized by the noun"sportsmanship." Ugo Guidi’s monument to the Footballers can be read in this sense: a hymn to sportsmanship.

|

| Ugo Guidi, Study for Footballers (1972; plaster, 47 x 28 x 15 cm; Pietrasanta, Museo dei Bozzetti) |

|

| Ugo Guidi, Calciatori (1974; travertine, h. 300 cm; Florence, FIGC Federal Technical Center, Coverciano) |

The studio would be transformed by the sculptor into a monument in 1974, at the Ghelardini studio in Pietrasanta, but it would be installed in the Coverciano Center and inaugurated only in 1979, two years after Ugo Guidi’s death. During our last visit a few years ago, we found the work in need of cleaning (we hope that those in charge of conservation have taken care of it in the meantime). In the meantime, we would like to imagine that nowadays the great champions whom all the boys esteem, starting with those who came out of the last European Championships with their heads held high, when they train with their teammates often find themselves passing in front of the Ugo Guidi monument, which is moreover included in the itinerary of the Coverciano Football Museum and can therefore be admired by all visitors. Because, at the risk of being trivially rhetorical, who ever said that art and soccer should be on two distant planets? Ugo Guidi’s Footballers are there to prove that the connections are closer than one might commonly think. Right there, where the national team’s soccer players train.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.