We cannot and must not forget the horrors of the Holocaust because only memory ensures that mistakes and horrors are never and never again repeated. The racial persecution of Jews in World War II was one of the greatest tragedies in History: unprecedented cruelty and inhumanity, but also inexplicable, for how could anyone think of disrupting and destroying the lives of thousands of people with the goal of wiping a race off the face of the Earth forever because it was considered, by the Führer and his followers, the Nazis, to be inferior? Inferior to whom? To people, if they could be called such, capable of killing for no reason at all, with unparalleled coldness, of firing a gunshot straight into the heart of an innocent man with terror in his eyes and face, or of putting human beings with bodies already visibly tried by the hardships and cruelties they endured into gas chambers, and who perhaps also had families, children. How could anyone be capable of such a thing?

This is why literature, art, and cinema become tools to expose the horrors of persecution and to make people understand, by narrating History and stories of “life,” how that was one of the darkest periods of humanity. In order not to forget and never to have it repeated. We too, as we have been doing for a few years now, try to make our small contribution to this great cause by telling the story of Jews, victims of the Holocaust, who were artists or who through art narrated and witnessed this dark period.

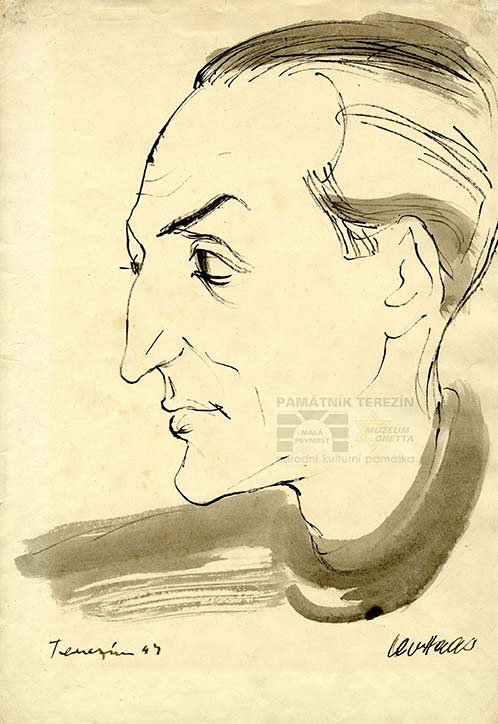

We tell you today the story of BedÅ™ich Fritta (VišÅˆová, 1906 - Auschwitz, 1944), an artist of Jewish origin. He was born on September 19, 1906, in VišÅˆová, in northern Bohemia. Educated in Paris, he later moved to Prague, where he worked as a technical draftsman, graphic designer and cartoonist under the pseudonym Fritz Taussig, and from the early 1930s began to work regularly as a caricaturist for the Munich satirical magazine Simplicissimus.

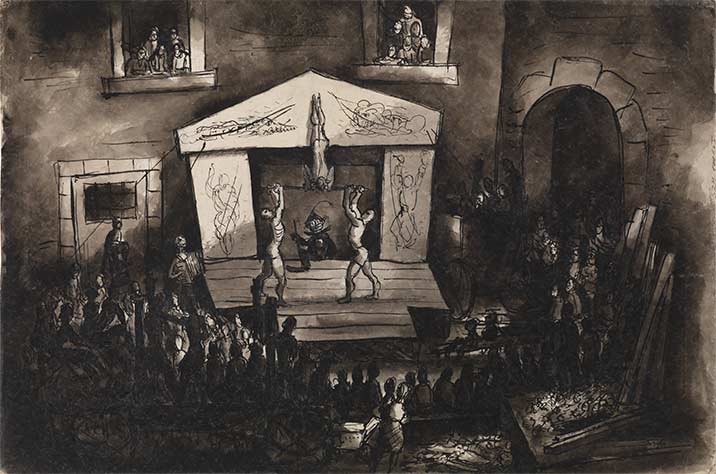

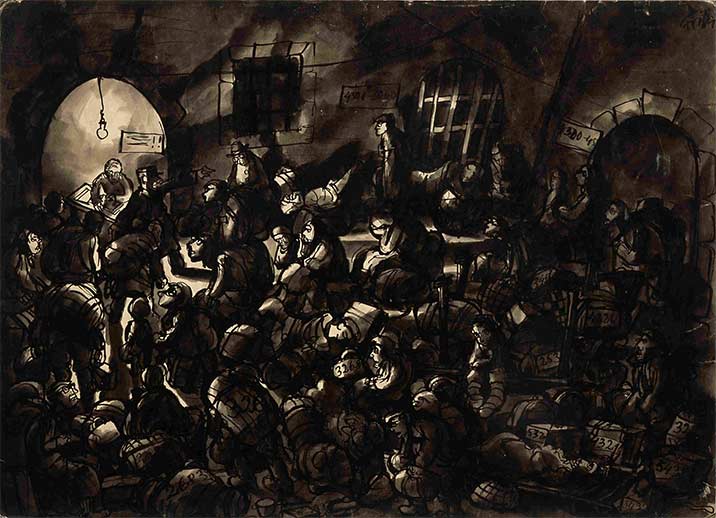

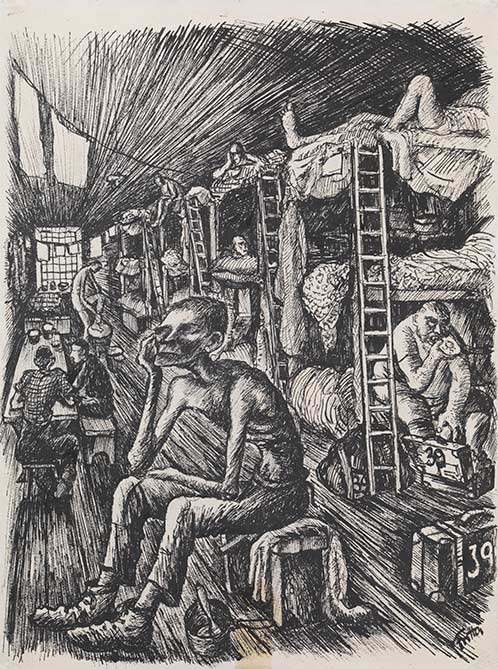

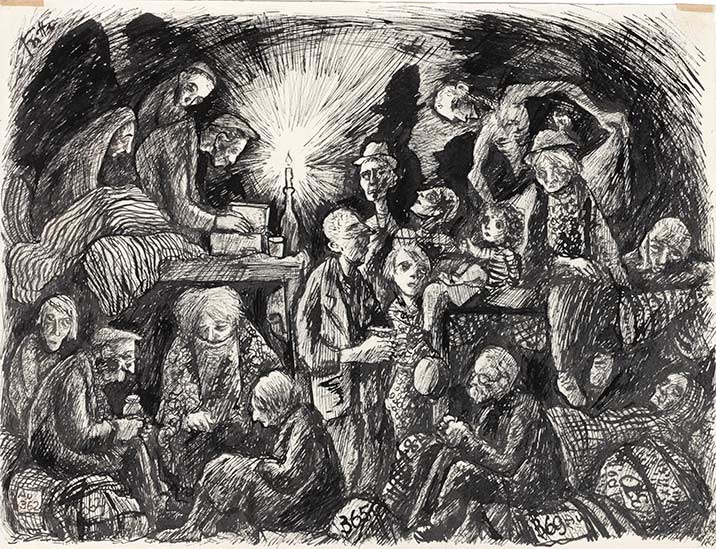

During World War II, he was deported to the Terezín ghetto on December 4, 1941. The Theresienstadt fortress, north of Prague, was in fact turned into a ghetto at the end of 1941.There were about 140,000 Jews from Central and Western Europe who were interned in the ghetto before being deported to extermination camps in the East. Here Fritta became head of the Technical Office and his job was to draw up building and technical plans, and in particular to draw up charts, statistics and reports that the SS Command continually requested. Everyone, and especially the International Red Cross, was supposed to believe that Theresienstadt was a normal town, where Jews lived isolated but in acceptable conditions. At least twenty artists worked in the technical department, as well as engineers and craftsmen; officially, the materials requested by the SS Command were in fact supposed to give the ghetto apublic image of a perfectly functioning and self-governing place, but the artists in the Office secretly used unofficial drawings to document the miserable conditions in which the ghetto was located. A large collection of drawings therefore portrayed daily life in the ghetto and a depressing and harsh reality, inspired by the style ofGerman expressionism: overcrowded housing, starvation, hearses, death.

Theresienstadt artists included Otto Ungar, Leo Haas, Ferdinand Bloch.

In the summer of 1944, however, the SS discovered the unofficial drawings and convicted Fritta and the other artists on charges of “spreading terror propaganda.” These were then imprisoned in the Gestapo prison in the Lesser Fortress along with their families, including Fritta’s son Tomáš, only a few years old. His wife soon died of hardship. After three months in prison, BedÅ™ich Fritta and Leo Haas were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp. There in November 1944 Fritta died, while Haas managed to survive and decided to adopt Tomáš.

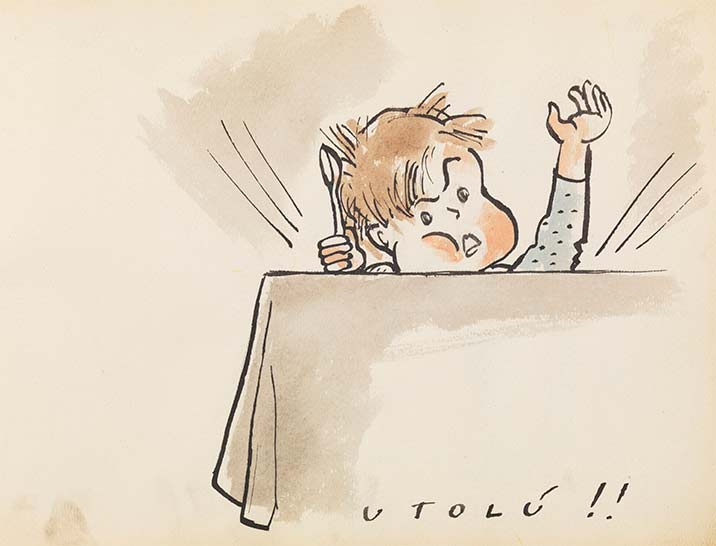

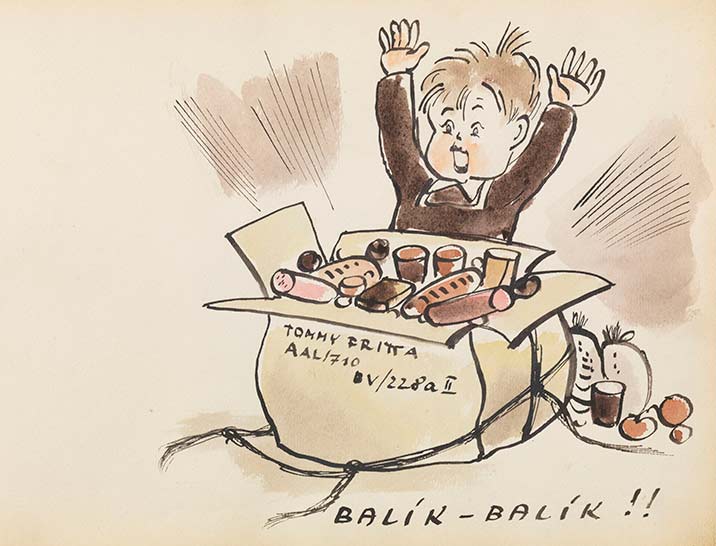

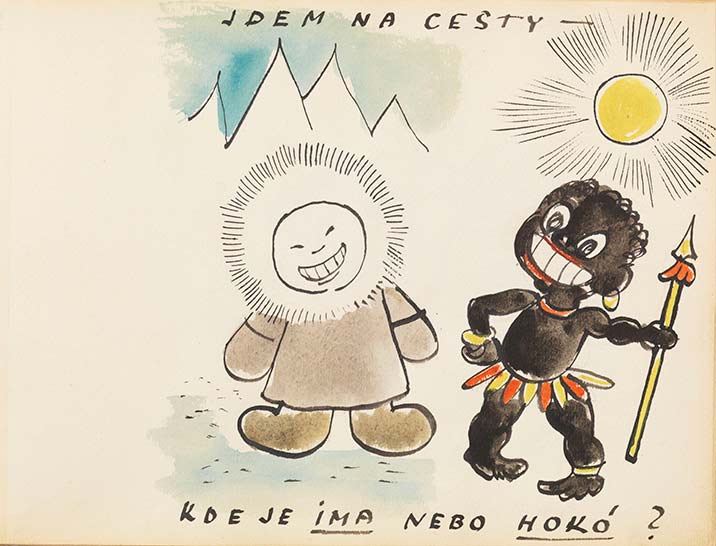

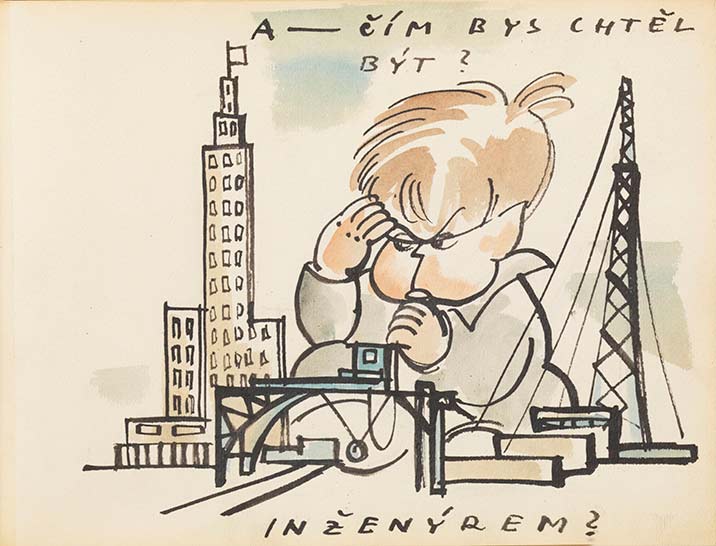

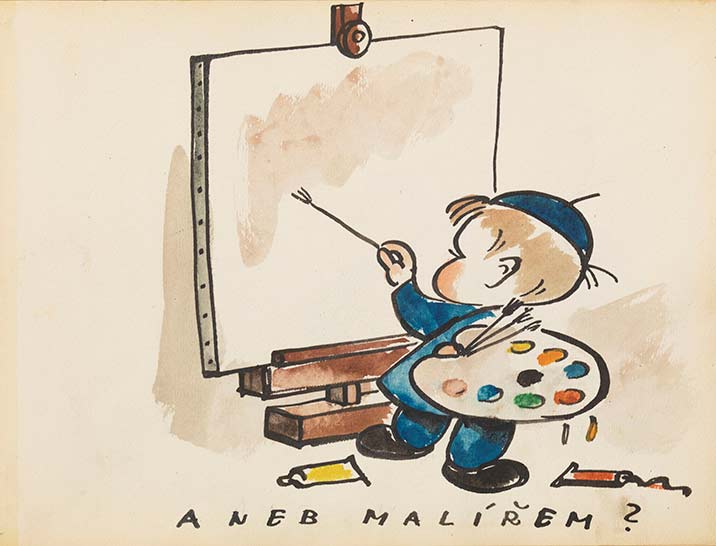

For his son’s third birthday, BedÅ™ich Fritta had made an album of color drawings, which was found hidden in the Terezín ghetto when it was liberated. Unlike the expressionist ink drawings that depicted the misery of daily life in the ghetto in black and white, in the album dedicated to his son BedÅ™ich cheerfully illustrated moments of the little boy’s life inside Terezín in a more dynamic and pleasant as well as colorful style. Tomáš portrayed while tapping his spoon on the table because he was hungry, Tomáš while looking in the mirror or while opening a package full of good things to eat (hunger and food are constant elements). Many of the drawings also illustrate imaginary journeys of father and son to exotic and distant lands, and others depict Tomáš in the role of engineer, painter, or other trades that the child might have taken up when he grew up. Adopted by Leo Haas and his wife, Tomáš lived with his adopted family in Mannheim, West Germany. And holding his real father’s scrapbook in his hands, he said, “It is the only thing that remains to me, that belongs to me, that was made just for me, it is my book, a book of my father. In that book I feel him, his tears, his hope, his fear.”

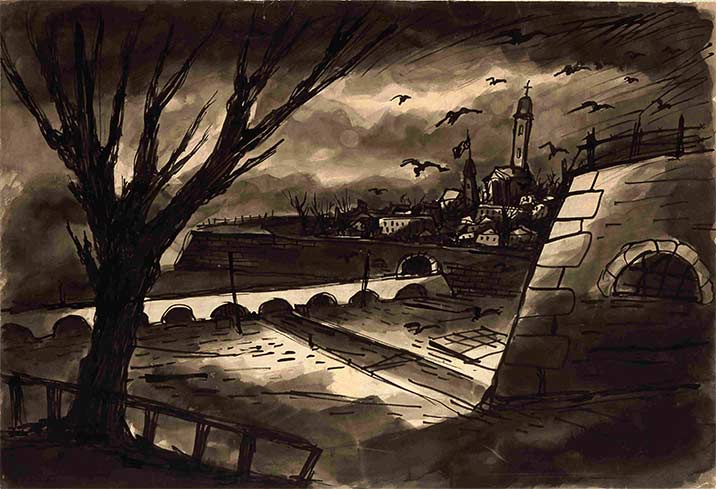

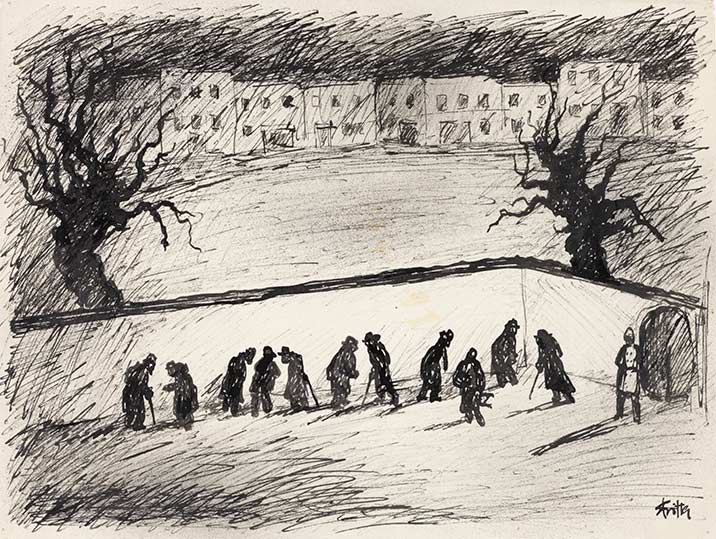

Some of Fritta’s surviving drawings are now preserved at the Jewish Museum in Berlin (which has also dedicated a rich online exhibition to BedÅ™ich Fritta, which is very useful for learning more about his story and life in Theresienstadt) and the Jewish Museum of Switzerland. Drawings that express disquiet, fear, inhumane conditions: one depicts, for example, a woman as she waits to be deported to Auschwitz; another shows the gathering area of the ghetto where new arrivals were gathered, with their numbered luggage, or from which people left for Auschwitz; still others show bedrooms in a former store or attic, a workshop for repairing military uniforms, the overcrowded mass dormitories (at first populated by 7,000 people, Theresienstadt later came to house up to 50,000 inmates at a time), or a long line of people with weight on their shoulders leaving the ghetto for Bohušovice station, which was more than two kilometers away: from that station they would then be put on trains bound for the extermination camps in the East. From June 1943 the trains would then depart directly from the ghetto. The Tower of Death, on the other hand, alludes to the headquarters tower: in the basement was a prison where prisoners were locked up and tortured.

In ink, and finished with brush and water, these drawings show BedÅ™ich Fritta’s skill in using chiaroscuro and creating sharp contrasts of light and shadow; illuminated sections contrasting with the darkness of bedrooms, workshops, warehouses, and ghetto streets. Often the faces and gestures of the characters render the figures as a kind of caricature. Objects and natural elements may finally allude to death, as in Abandoned Luggage, where bare trees, abandoned luggage, and a dark, dark sky speak of the absence of life. Of a sad end to history.

Theresienstadt became a real town of deported Jews: the propaganda film The Führer Gives a Town to the Jews, which was presented to the International Red Cross, was also filmed in it. It actually served as a stalling point for people who were later deported and killed in Auschwitz, and conditions in the ghetto were very harsh: from poor food to very precarious housing situations. However, the events of Theresienstadt are intertwined with the lives and stories of many artists and musicians, for it was here that a high number of musicians, intellectuals and artists were concentrated who also worked within the ghetto to hold concerts, lectures and cultural activities aimed at alleviating through various forms of art the suffering of children and adults.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.