It is above all to the art historian Andrea Emiliani (Predappio, 1931 - Bologna, 2019) that we owe the rediscovery of a genius of seventeenth-century Ferrarese art, Carlo Bononi (Ferrara, c. 1580 - 1632), whom in 1962, Giacomo Bargellesi lamented in an article published on March 2 of that year in the Gazzetta Padana, his fellow citizens did not know or appreciate sufficiently. And it was precisely 1962 that constituted an important milestone in the critical journey that accompanied the resurgence of Carlo Bononi, his rebirth from the oblivion to which he had been relegated for long centuries: Emiliani, at the time a young scholar of only thirty-one years of age, gave to the presses his monograph on the painter, the first that was dedicated to him. Capturing attention on Bononi had been, some thirty years earlier, Roberto Longhi (Alba, 1890 - Florence, 1970), who had placed him at the conclusion of his 1934 Officina ferrarese (and later expanded in 1940): a “contrasting and dossesque” artist, distinct “from contemporary Bolognese,” Bononi was for Longhi the painter who, in the Pietà in the Louvre, “barely accommodates to the carraccesca the clear memories of old Ferrara, passionate and chivalrous , and does not fail to scatter on the ground the last fragments of Alfonso d’Este’s famous armories,” and who in the private collection Narcissus reaffirmed his Dossesque nature by taking care to paint a clear marble basin that “seems to reflect the last dreamer of a declining world, veined now by the sadness of Tasso.”

“Last dreamer”: with these terms, taking up Roberto Longhi’s so evocative expression, the great exhibition on Carlo Bononi held at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara in 2017 also referred to the artist. The painter lived through the city’s most difficult season, the season of decline: it was 1598 when the Devolution marked the passage of the Duchy of Ferrara to the Papal States for hereditary reasons, and the Este court had to move to Modena. Ferrara, however, remained a productive artistic center even under the Church, since it was necessary to satisfy the needs of a large group of new collectors, and the artistic production of the city, in the seventeenth century, reached decidedly high levels: this is what the most up-to-date criticism has rightly emphasized, erasing the unfavorable judgment of the nineteenth century, which spread like a veil over the Ferrara seventeenth century, covering even its highest and most glorious achievements, not considering it up to the level of what the city had produced previously. But it was still the sunset of an era, and Bononi’s star shines in these years, like a bright star imbued with nostalgia, like a “curtain still majestic and speckled with senses and counter-senses” (so would Emiliani have written) destined to fall on this age, situated between the spells of Dosso Dossi and the annexation of Ferrara to the Church State, an age “ranging from Ariosto to poor mad Torquato and his very sad Ferrara imprisonment, existential, disturbing, modern.” These are the coordinates Emiliani drew for his Bononi.

|

| Carlo Bononi, Pieta (ca. 1619; oil on canvas, 248 x 178 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

At the beginnings of this path, Emiliani placed the Miracle of St. Dominic in Soriano, which then more recent critics preferred to move to the 1620s, considering it a mature work, and executed at least from 1621, the year during which the cult of the miracle that took place in the village in the Sila mountains, which until then had been confined to Calabria, also spread to Ferrara, where the work is still preserved (although not in the church of San Domenico, the place of its ancient provenance, but temporarily in storage at the Archbishop’s Palace). Emiliani saw, in this miracle, an early work, animated by a manner capable of reviving “by sweet memories in numerous passionate ingredients” the “old touch” of Bastarolo, “mixed with a concrete and chromatically liquid tone.” it was the extraordinary strength of this painting that had struck the great scholar, the vivid and passionate description of the affections (see the faces of the three saints, accompanied by the putti holding their iconographic attributes), the freedom of an invention aimed at emotionally involving the subject, according to the most up-to-date norms of early Baroque culture. In the painting, it is we who take the place of Friar Lawrence of Grotteria, who, according to the hagiographic account, witnessed the apparition of the Virgin and the saints Catherine of Alexandria and Mary Magdalene, who are said to have left in the church of Soriano an Acherotipa canvas, still preserved today in the town’s parish church, although obviously believed not to have been painted by a divine hand, but more simply by a pupil of Antonello da Messina.

And then there is Bononi’s passage from Rome, brought to light by Emiliani’s careful study of the Fano paintings, those where the tangencies with Caravaggio’s art are most palpable, most notably in the San Paterniano che risana la cieca Silvia, where the light that invests the small throng gathered around the saint, where the sense that the whole scene was caught in the immediate and ephemeral excitement of a moment, where the self-portrait peeking out behind Paterniano’s curved back refers directly to the illustrious Lombard, but where explicit quotations from Merisi also abound: the man on the ground on the right is a precise reminder of the one that appears in the left corner of the Martyrdom of St. Matthew in the Contarelli chapel, and the same is true of the gesture of the onlooker pointing to the miracle of St. Paternianus, an obvious reminiscence of the arm of Christ rising in the Vocation of St. Matthew to call the apostle. But Bononi was also capable of “evading,” for Emiliani, that “direct Caravaggesque descent” always with the filter of his freedom, “in a sort of chromatic and compositional excitement; in a crowding of gestures and attitudes enclosed within the two side wings, with a perspective flavor.” A Caravaggio revisited through the feast of colors of a Lanfranco, one would say. And the canvas that, in the church of Santa Maria Assunta in Fano, flanks on the left the painting with the miracle, or the Vision of St. Paterniano, is for Emiliani “perhaps the masterpiece of the artist’s entire activity,” as he had to write in his contribution for the 2017 exhibition catalog: “with high, impetuous conspicuousness,” we read, "Bononi invests on the dark silhouette of the almost slumbering saint, while on his face, as on his long hands, a terrestrial physiognomy of his own with a naturalistic flavor of decided portrait taste and almost of still-life“ And again: ”a painting not to be disliked by the coeval, early Fabriano stay of Orazio Gentileschi; or by the modest purchasers of Giovan Francesco Guerrieri da Fossombrone after the Rome trip; if not even by the more convulsive Saints’ lovers of Angelo Roncalli known as Pomarancio."

|

| Carlo Bononi, Miracle of Soriano (1621-1626; oil on canvas, 270 x 143 cm; Ferrara, Church of San Domenico, Chapel of St. Thomas dAquino. In temporary storage at the Archbishop’s Palace) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Saint Paternian Healing the Blind Silvia (1618-20; oil on canvas, 310 x 220 cm; Fano, basilica of San Paterniano) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Vision of Saint P aternianus (1618-20; oil on canvas, 310 x 225 cm; Fano, basilica of San Paterniano) |

By Andrea Emiliani’s own admission, following Bononi’s path is not a simple matter: eclectic, accustomed to moving in different directions, always sensitive to the newest and most disparate stimuli he encountered, perhaps making journeys. Bononi’s geography seems to have as its cardinal points Bologna, Mantua, the Marches. The coordinates are traced by Ludovico Carracci, Tommaso Laureti, Giulio Romano, Federico Barocci, Andrea Lilli, Orazio Borgianni, Guerrieri. The orientations of Bononi’s taste and interests range from one region to another. It is, however, the encounter with Guido Reni that Emiliani considers a fundamental stage in the artist’s path, so much so that he considers theAscension of the church of San Salvatore in Bologna, a work that depends on Reni’s solutions, the masterpiece that marks the beginning of the artist’s maturity (Emiliani placed it in 1617; today, however, we tend to consider it executed ten years later). Yet Bononi was not satisfied with it: he had finished it after only thirty-seven days of work, and he believed that the result did not live up to expectations, since the hasty preparation gave rise to darker hues than the painter was looking for. In the composition, Christ rises lonely over a gloomy sky over which clouds here and there are illuminated by the faint light of the moon: he is depicted with a slight undertow, his right arm raised, his face exalted by the glow of his halo, his robes swollen by the rising air. In the lower register, the apostles crowd in, natural and individually characterized, with the Virgin in the center, in a slightly elevated position: amazement, astonished gazes, confusion, the figures arranged according to a very studied rhythm that almost follows the steps of an imaginary dance. Emiliani placed theAscension in relation to theAssumption of the Virgin, which Guido Reni executed for the Gesù church in Genoa and which Bononi must have seen in the home-studio of his Bolognese colleague on Via delle Pescherie: Carlo, referring to the layout that Guido had devised for theAssumption, learns of this painting, “as is to be expected,” Emiliani specified, “lampio desiderio compositivo, this horizontal palpitation of the bodies, barely burdened by the colorful outburst of the sky.”

At the conclusion of Bononi’s parable, Emiliani placed some of the most virtuosic and at the same time most mannerist works of the Ferrara painter’s production: the example of the Marriage at Cana now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara, an enormous painting over seven meters in length made in 1622 for the refectory of the Certosa, is worth all of them. A painting exemplified perhaps on the model of Federico Barocci’sLast Supper, to which refer the perspective cut, the setting, the compositional scheme, the exuberance in the details (most tasty is the dog that bites the servant in the foreground, who tries to escape the bite of the beast, exquisite is the concert improvised on the balustrade above and foreshortened below). Barocci’s splendid Urbino still had a court, Ferrara, on the other hand, had not had one for more than twenty years: and perhaps Bononi’s dreamy nature lingered on those details (the richly dressed young men, the girls carelessly and with affected gestures eating while trying to attract attention, the concertino itself) to evoke the splendor of an Este Ferrara he could only imagine: “the last representative of ancient Ferrara closes in tight autonomy of language, while still attentive to the facts of the capital, to the fanciful legends, at once harsh and dreamy, born and absolved on the banks of the Po.”

|

| Carlo Bononi, Ascension of Christ (c. 1627; oil on canvas, 450 x 380 cm; Bologna, San Salvatore). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Guido Reni, Assumption (1616-1617; oil on canvas, 442 x 287 cm; Genoa, Chiesa del Gesù) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Wedding at Cana (c. 1632; oil on canvas, 355 x 688 cm; Ferrara, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

|

| Federico Barocci, Last Supper (1590-1599; oil on canvas, 299 x 322 cm; Urbino, Duomo) |

|

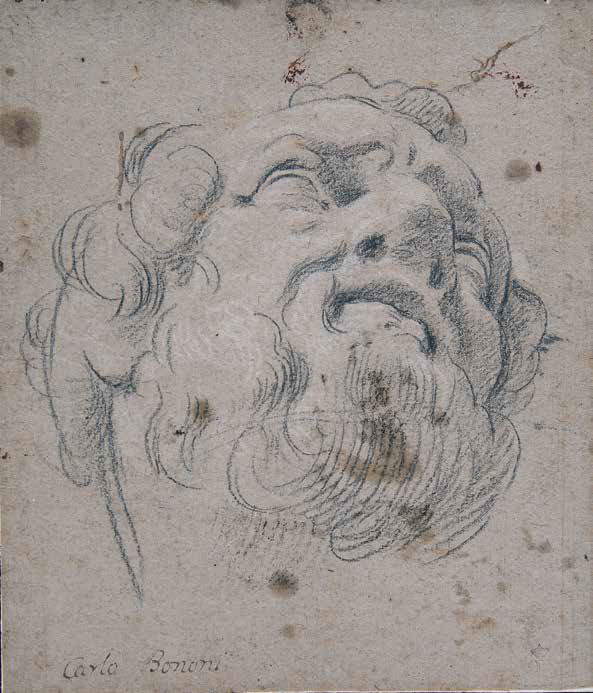

| Carlo Bononi, Male Head (1616-1617; black stone, white chalk, brown paper, counterfoiled, 236 x 205 mm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera, Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Inv. 173) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Genius of the Arts (1621-22; oil on canvas, 120.5 x 101 cm; Lauro Collection) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Guardian Angel (c. 1625; oil on canvas, 240 x 141 cm; Ferrara, Pinacoteca Nazionale) |

In between, other major episodes. The publication of a valuable Male Head, a study now in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe of the Pinacoteca di Brera, attributed by Emiliani to Bononi, then questioned and finally returned with force and conviction to the Ferrara painter. The study of the Genius of the Arts, which reappeared in 1962 and is now considered among the main works of Bononi’s production. And again, the examination of the relationship with Guido Reni, which passes through the sensual Guardian Angel, a work that nevertheless, according to Emiliani, has as its protagonists figures that “assume a noble elegance, an affected gestural expressiveness that seems almost to dilate in the meditatively cold atmosphere that pervades the painting”: an atmosphere that, in the scholar’s opinion, descended from Guido Reni’s equally delicate finesse. Intuitions partly elaborated in an early essay in 1959, which came at the same time as the exhibition of eight of Bononi’s canvases at the exhibition on the Masters of seventeenth-century painting in Emilia held that year at the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio in Bologna, as part of the Biennali d’Arte Antica conceived by Cesare Gnudi and begun in 1954 with a monograph devoted to the genius of Guido Reni and curated by Gnudi himself. At the time of the review on the masters of the seventeenth century, Emiliani was just twenty-eight years old, and that was the first time that a survey of Bononi’s art was undertaken.

Three years later, as mentioned at the beginning, would come the first monograph, written for the Cassa di Risparmio di Ferrara and built on the basis of documentation that was still scarce at the time, since archival research on Bononi had just begun, and resources were therefore limited. It was that dense and highly elegant work by Emiliani that revived the critical fortunes of Carlo Bononi, whose greatness the scholar was perfectly aware of. In the opening lines of the introductory essay, he described him as a “son of a Po Valley duchy of strict cultural homogeneity”as an artist who, strengthened by a “memory still so intact and alive of the great artistic events of his land,” was able to rediscover “almost suddenly and without perceiving the well otherwise undermining suggestions of the Counter-Reformation, a taste for painting, a full narrative voluptuousness, an inventive freshness still grafted (albeit in the reflective and introverted change of the new psychology) directly into the great exemplars of a past still alive and historically immanent.” A past of which Bononi was an extraordinary heir.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.