There are colors that are remembered. Carmine red, cobalt blue, Veronese green. Then there is Payne’s gray: a hue that seems made not for shouting, but for remembering. Giulia Andreani employs it as if it were a form of language. Not a hue, but a code. A code that speaks of forgotten women, of faceless powers, of ghosts that do not want to stop inhabiting history.

Born in Venice in 1985, Giulia Andreani lives and works in Paris. Her training inart history and her interest in the iconography of power and collective memory nurture a painting practice based on archival investigation and critical interpretation of the past.

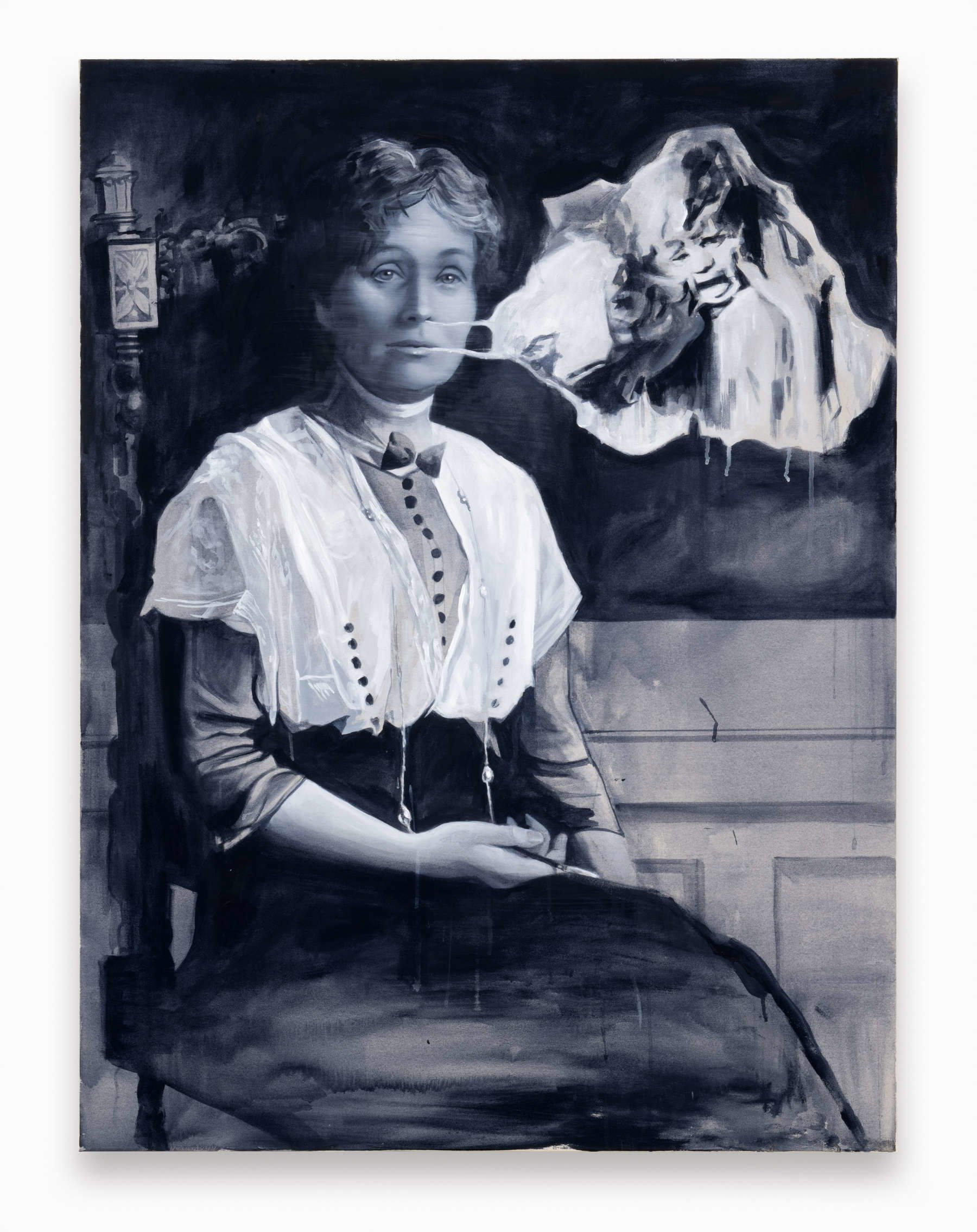

His works disorient. For there is something in the faces of the characters depicted, in the way they are portrayed, not heroically, not tragically, but with a kind of reluctant dignity that compels one to stay. To look. To wonder: what am I really seeing? And that is where Andreani’s work begins. Not in the painting itself, but in the movement it induces in the viewer. His is a living archive, a device that destabilizes rather than reassures. Each image is taken from historical, photographic, military, health, domestic archives. But it is never simply a pictorial transcription: the image is stripped, reassembled, made enigmatic. There are women in uniforms, mothers with blank stares, little girls who already look old. We do not know what they have experienced. Yet, somehow, we know them. They are part of a silent knowledge, inscribed in our bodies.

Consider the series TheUnproductive (2023), one of the most radical moments of his recent production. In those works, Andreani brought to light women whose social role had been defined negatively: not productive, not fertile, not conforming. Painting, however, restores her power. It makes them exist. It fixes them on a surface where they can no longer be ignored. But beware: this is not “rehabilitation.” Andreani does not redeem. He does not save. Simply: he shows. And he lets painting ask the questions. This is the miracle of Andreani’s painting: it manages to restore density to time. Not to represent it, but to delay it. To make it happen again. Each painting is an opaque lens through which the past manifests itself without clamor, but with a gravity that leaves no escape. And in an age like ours, in which everything seems to have to be immediate and transparent, this act of opacification is deeply political.

His work exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2024 is a prime example. The faces of the suffragettes, the elusive figure of Madge Gill, the glass sculpture that becomes a diaphanous body and silent manifesto: everything seems to belong to a parallel history, not alternative but underground. As if Andreani is trying, patiently and without rhetoric, to rewrite history from a lateral point of view. Not from the center of events, but from the folds, the interstices. And in those margins, he finds the essence.

But perhaps more than rewriting, Andreani interrogates. Not History with a capital letter, but the small, everyday, feminine, sideways one. The history of bodies, of silences, of messy archives. Her figures do not seem to belong to the past, but to a memory in constant becoming. They are not icons, they are presences. And like all presences, they disturb. They confront us with our responsibility to see. And so his gray is not just an aesthetic. It is an ethics. It is the choice not to seduce with color, but to insinuate with form. Of not restoring truth, but evoking complexity. Like a recurring dream that stubbornly resurfaces every night, with slightly different details.

Walking through Giulia Andreani’s painting is an act of resistance. To simplification, to speed, to erasure. It is an invitation to take time. To pause. To look at what has been left out. And to ask ourselves, without pretense of answers: how many images are still missing? How many stories are waiting for a surface on which to settle? And above all: are we willing to let them pass through us? In an age that rewards visibility and penalizes complexity, Andreani’s work reminds us that there is another way of looking. A slow, difficult, but necessary gaze. A gaze that does not consume, but preserves.

And perhaps that is what remains after viewing one of his paintings: not so much the image as the wound. Not so much the form as the emptiness he draws. A gray that does not forget. A shadow that, miraculously, continues to illuminate.

The author of this article: Federica Schneck

Federica Schneck, classe 1996, è curatrice indipendente e social media manager. Dopo aver conseguito la laurea magistrale in storia dell’arte contemporanea presso l’Università di Pisa, ha inoltre conseguito numerosi corsi certificati concentrati sul mercato dell’arte, il marketing e le innovazioni digitali in campo culturale ed artistico. Lavora come curatrice, spaziando dalle gallerie e le collezioni private fino ad arrivare alle fiere d’arte, e la sua carriera si concentra sulla scoperta e la promozione di straordinari artisti emergenti e sulla creazione di esperienze artistiche significative per il pubblico, attraverso la narrazione di storie uniche.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.