The following article is an adaptation of the essay Inconsistent arts: neither censorship nor honor, therefore by Johann Naldi published in the catalog of the exhibition Henri de Toulouse Lautrec. Paris 1881-1901 (Rovigo, Palazzo Roverella, February 23 to June 30, 2024), Dario Cimorelli Editore.

On February 4, 2021, the daily newspaper “Le Monde” published an important article by Philippe Dagen announcing the discovery of seventeen unpublished works of the Incoherent Arts. Until then, the production of this legendary movement born in the late nineteenth century, whose intent was to challenge through laughter-but not only that-the seriousness of the art world, was known only through exhibition catalogs and the numerous articles that came out in the press at the time; the reappearance of those works is thus bound to change the view of their history.

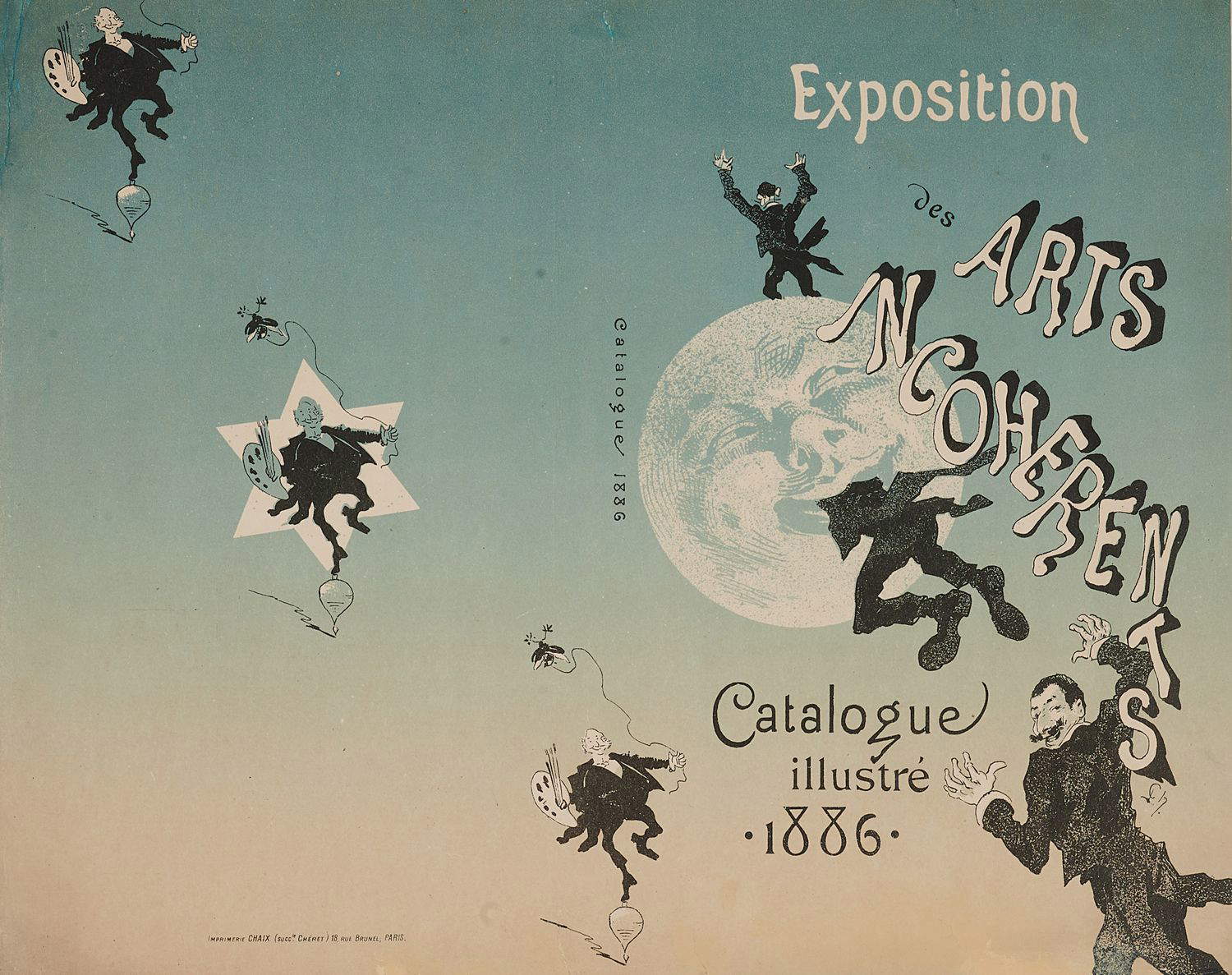

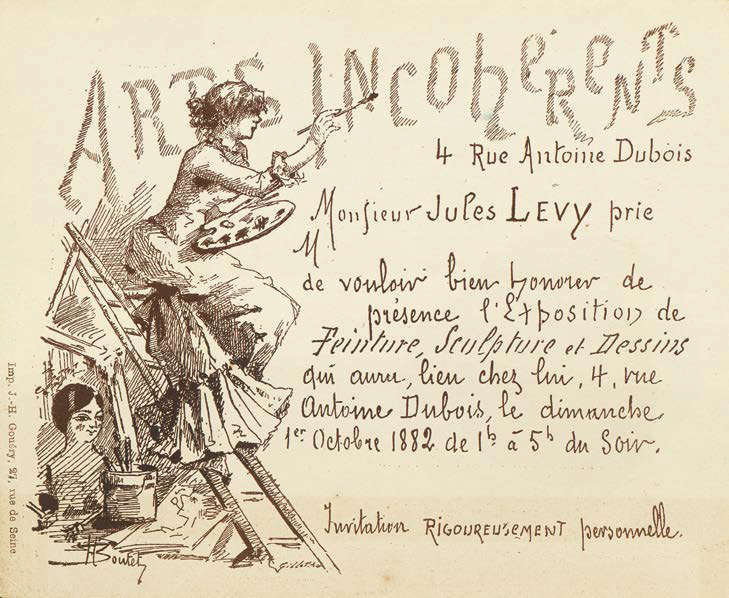

Created by the barely 25-year-old journalist and publisher Jules Lévy (1857-1937), the Inconsistent Arts movement set out, from 1882 to 1893, to subvert the set of norms governing the world of fine arts. Its initiator’s credo: “Exhibit works by people who cannot draw.” Reiterating the total antithesis to the highly respectable official Salon, one does not have to be a professional painter or sculptor to be a member of the Incoherents, although numerous established artists, including Toulouse-Lautrec himself, make contributions in mounting exhibitions. The writer, actor or mere amateur is welcome, without running the risk of having his or her work rejected by a jury opposed to violations of academic conventions. Only so-called ’obscene’ works are banned. Prizes are awarded by drawing lots and winners decorated with chocolate medals. Neither censorship nor honor, then. Bringing to the fore the most incongruous media and materials - gruyere sculptures, painted live animals scampering through the exhibition halls, frames without canvases or canvases without paint... - the six hundred or so participants, who in most cases work under pseudonyms to better affirm the group spirit, produce and exhibit a thousand works in a decade of activity. The first official exhibition was held on October 1, 1882 in Jules Lévy’s tiny room. A scant ten square meters in which are crammed one hundred and fifty-nine pieces, listed for the occasion in a supplement to the magazine “Le Chat Noir.” Among them is Paul Bilhaud’s dazzling Combat de nègres pendant la nuit [Negro fight in the night], the first monochrome painting presented as part of a public exhibition, which instantly becomes part of the myth. The event is noteworthy and has international resonance. On the strength of its success, Jules Lévy replicates as early as the following year. On this second date, Alphonse Allais hangs on the wall a simple white bristol card titled Première communion de jeunes filles chlorotiques par un temps de neige [First Communion of Chlorotic Little Girls in Snowy Weather], of which no trace has ever been found. In 1884, the catalog reviews two hundred and twenty-four pieces, not counting any out-of-print. Once again, the exhibition arouses interest far beyond the boundaries of the capital. [...].

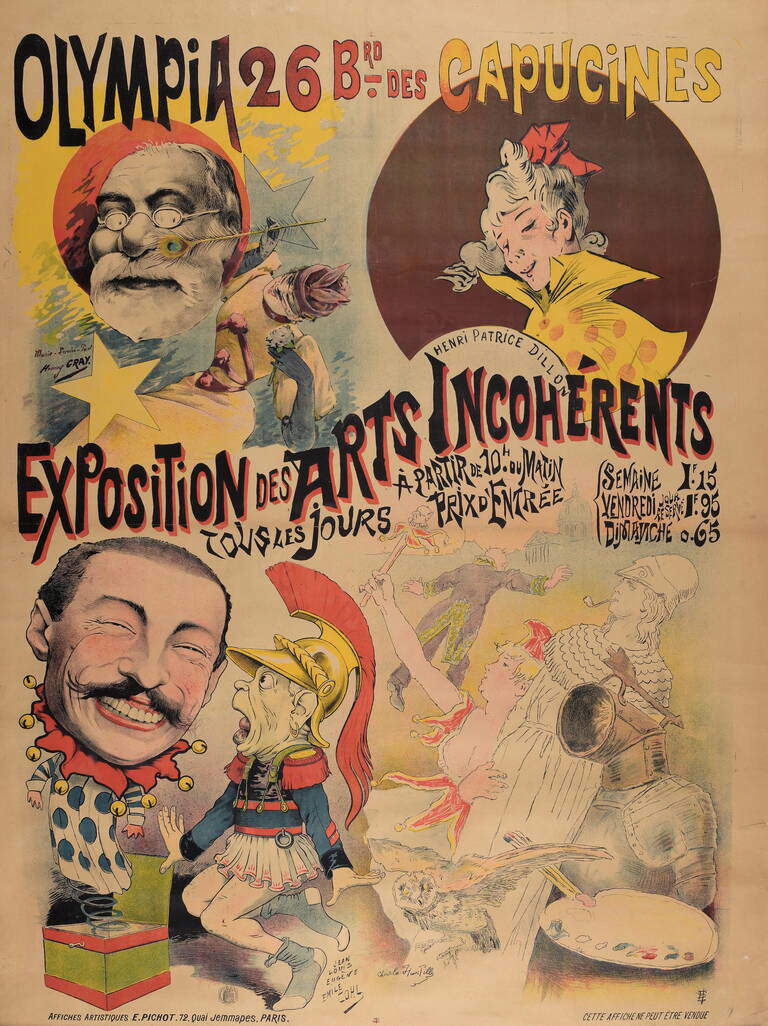

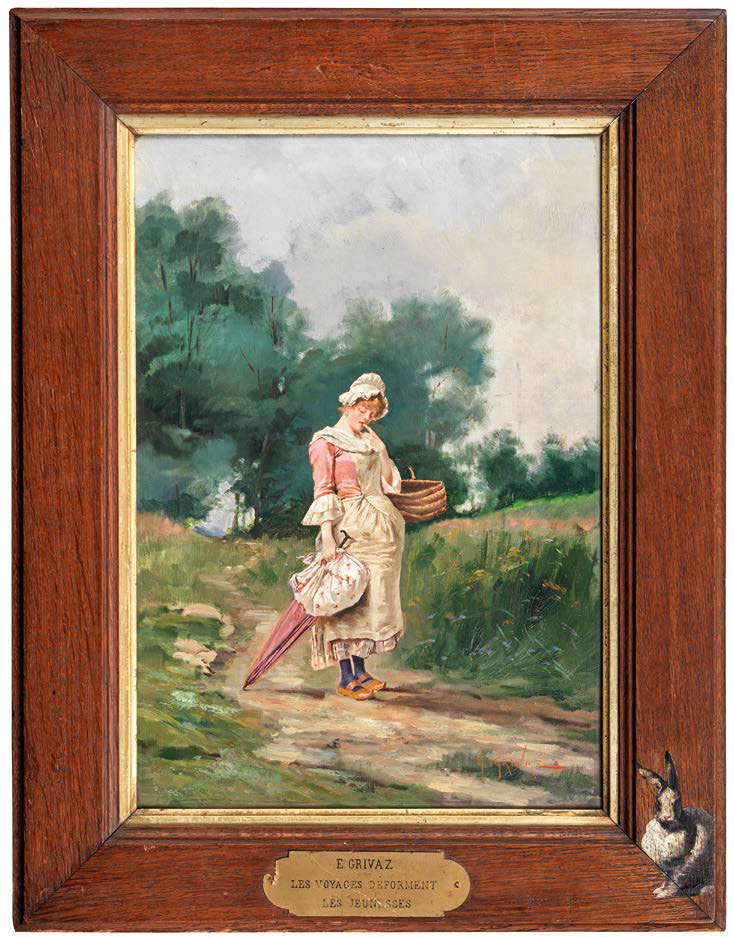

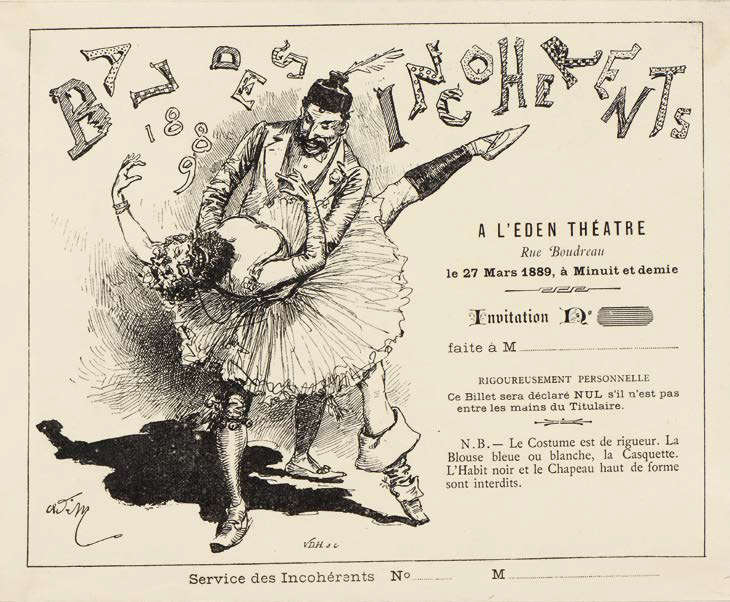

No exhibitions are held in 1885, but a first ’incohérents ball’ is launched, held on rue Vivienne, which promises to be no less picturesque. Invitees are asked to show up masked in the most whimsical manner possible-as an artichoke or a bedside table, as they choose-while a sign at the entrance to the hall announces “Melancholy forbidden.” Over the course of thirteen years, several such balls would follow, punctuating Parisian life under the banner of a subversive madness whose memory the Dadaists would cherish. In 1886 the indefatigable Jules Lévy organized a new exhibition that included a hilarious painting by Eugène Grivaz, Les Voyages déforment les jeunesses [Voyages deform youth], which would be the subject of commentary in several newspapers: "This exhibition is a jumble of oddities, laughter, surprises and extravagances of which I can only quickly point out a few examples. These include Les Voyages déforment les jeunesses, a delightful canvas in which a little girl, gracefully painted, returns from afar with a bundle on her shoulder-and another elsewhere." In 1889, taking advantage of the Universal Exhibition, Lévy mounted a major retrospective of Incoherent Arts with more than four hundred works, in which the stunned visitor came across a horse free of fetters, painted entirely in the colors of France. The last glimpse of incoherence, the 1893 exhibition is organized in the grand foyer of the brand new Olympia concert hall on the boulevard des Capucines. Paris is papered with the ’collectivist’ poster announcing the event, executed in collaboration by Dillon, Cohl, Ferdinand and Gray. In the face of undisputed popular success, critics are divided, torn between disdain, contempt and unqualified support. In addition to the seven Parisian exhibitions, the movement also moved outside the capital, to Rouen, Bourg-en-Bresse, Nantes, Lille, Besançon, Nancy, and Grenoble, where local artists mingled with the Incoherents who had come from Paris.

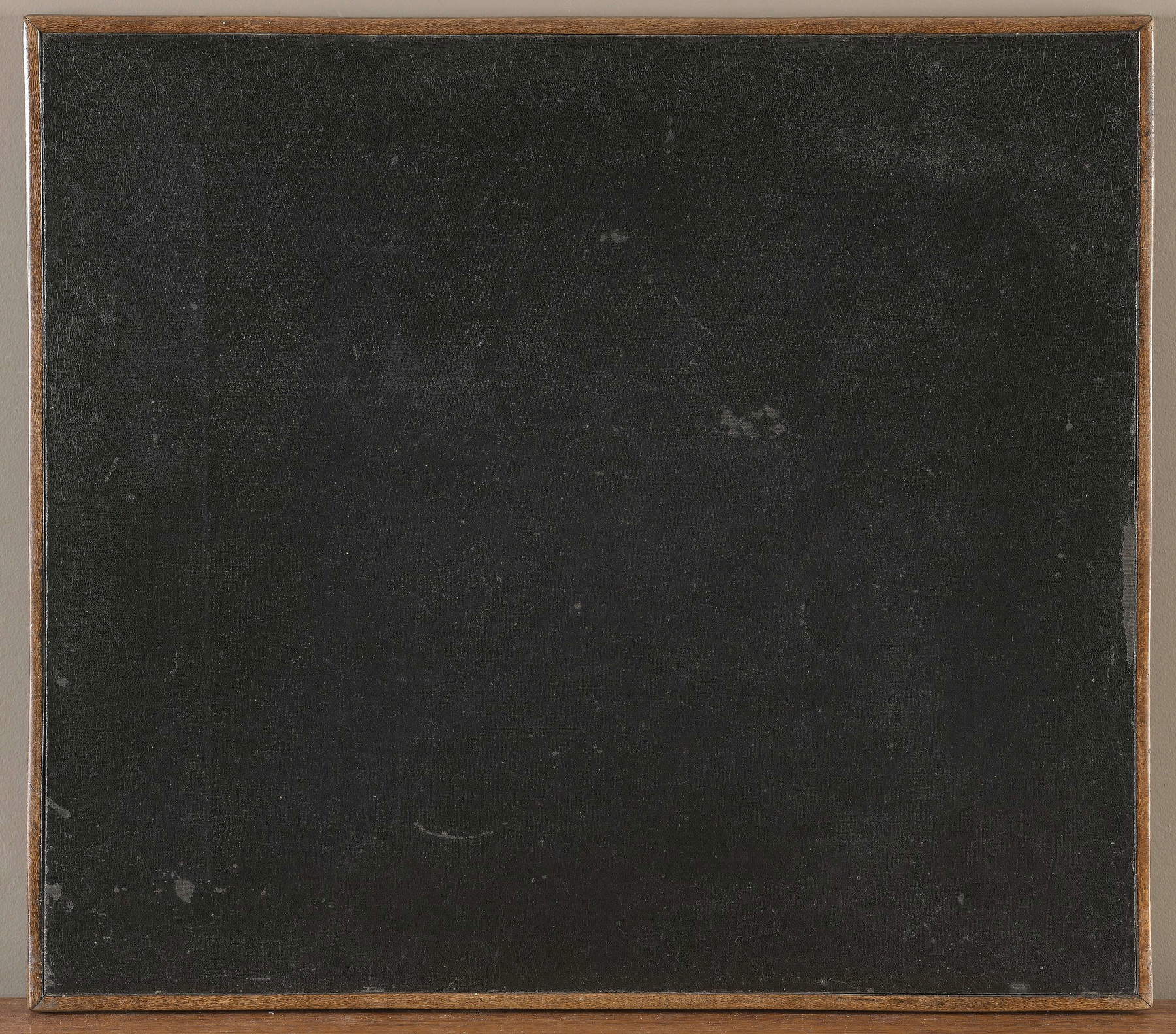

Discovered in 2017 in a private collection in the Paris region and classified a National Treasure by the French state, the pieces on display [ed. note: at the exhibition Henri de Toulouse Lautrec. Paris 1881-1901, in Rovigo, Palazzo Roverella, from Feb. 23 to June 30, 2024], presented for the first time outside French borders, constitute unhoped-for study material for the history of the fin-de-siècle avant-garde, whose anticipatory works Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, among many others, famously appreciated. Prominent among the finds is a fascinating uniformly black painting, the provenance of which is indicated by an old label affixed to the verso of the canvas with an inscription in neo-Gothic script: “Arts incohérents - 4, rue Antoine-Dubois, 4, PARIS.” The reference to the art movement that shook the capital throughout the 1880s is thus explicit. A second label bearing the number 15 links the painting even more precisely to the exhibition catalog published on October 1, 1882 in “Le Chat Noir,” revealing its title and author: it is indeed that Combat de nègres pendant la nuit executed by Paul Bilhaud, a famous vaudeville author who became a painter for the occasion-and not of the least. The newly rediscovered work is thus the mythical monochrome, the first example of its kind to have been exhibited as part of an official art event. Considered lost, or even destroyed for more than one hundred and thirty years, it had disappeared on the very evening of its public presentation, which in the tiny apartment had lasted barely four hours. Of the sixteen works unearthed and presented in one of the Inconsistent Arts exhibitions, one has attracted particular attention: the Rideau de fiacre [Curtain of a Carriage], consisting of a fragment of green silk protruding from a painted wooden cylinder. The object, of a common pattern, is accompanied by an inscription engraved on a metal plate: Des souteneurs encore dans la force de l’âge et le ventre dans l’herbe boivent de l’abs inthe [Protectors still in the prime of life and with their bellies in the grass drink absinthe]. The title, a redundant allusion to the color green, is followed by the monogram of Alphonse Allais, the celebrated ’absurdist’ whose no ’monocroidal’ work had ever been found. His Album primo-avrilesque, a true avant-garde object published in 1897 and elevated to the status of an icon of modern art by the Surrealists, constituted until the time of this discovery the only available material evidence of these prophetic productions.

Next to the first monochrome exhibited by Bilhaud-the Mona Lisa of the Incoherent Arts movement-there has thus reappeared a true proto-ready-made by Alisi dating from the late nineteenth century, the importance of which had long been known to be attributed to it-relatively unacknowledged-by Marcel Duchamp. To these two works of fundamental historical importance, of which no museum in the world can boast an equivalent, must be added a series of fifteen original works executed with different techniques, analysis of which shows that they were all presented in the successive exhibitions of the Incoherent Arts organized from 1883 to 1893. Many of them, in fact, we find in printed versions in the catalogs of the time, which, as we have seen, constituted until now the only material evidence available to the historian eager to further the study of this exciting movement. In 1992, the Musée d’Orsay had set out again to save it from oblivion by dedicating to this formidable moment in French art an exhibition that laid the foundations of recent research on the Inconsistent Arts, essentially presenting documents and interpretive reconstructions of lost works and noting the almost total disappearance of thousands of works produced by the six hundred or so artists who joined it over a decade. The rediscovery of seventeen original works thus constitutes a true event, offering the public and exegetes an opportunity to appreciate the material characteristics of the movement and refine their understanding of it. In other words: to distance oneself from a certain partially fictitious narrative of the Incoherent Arts asserted in recent decades by a good number of historians--mostly literary specialists who had had access only to documentary material--in order to redefine its creative modes on the basis of the works themselves. A close examination of the latter indeed reveals a special attention to ideation and formal refinement, most visible in Paul Bilhaud’s monochrome, which the vast majority of historians had hitherto ignored, hypothetically reducing the entirety of the production of the Incoherent Arts to the rank of grand farce without tomorrow. A kind of ’erasure’ act of a good-tempered movement that was not worth considering as one of the main living sources of the avant-garde of the following century. Instead. Today, the sincere veneration for it held by the father of Surrealism André Breton, whose immense collection of books and heterogeneous objects included a copy of Alphonse Allais’s Album primo-avrilesque, several catalogs of exhibitions of the Incoherent Arts, and numerous articles related to the movement, clipped here and there and annotated by Breton. He and his friend Paul Éluard seem to agree in attributing significant importance to the innovations of Allais, a major figure they cite on two occasions in their Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme, for Surrealism. The same can be said of Marcel Duchamp, the great theorist and popularizer of the ready-made who as early as 1904, not yet in his twenties, moved to his brother’s in Montmartre, where he frequented numerous illustrators who had participated in the Incoherent Arts exhibitions, including Adolphe Willette. Veneration that, moreover, would never wane according to Robert Lebel’s testimony that Duchamp died in 1968 with a book by Alphonse Allais in his hand. This lifelong admiration for the brilliant author - also a Norman - is evidently explained by the spiritual closeness Duchamp felt he had with this great genius of language who, thanks to his consummate art of ’mystification,’ had been practicing since the late nineteenth century--particularly in the context of the Inconsistent Arts exhibitions--a kind of ’’linguistic qualification of the object.’’ To the long list of artists and intellectuals fascinated by the movement and, to quote Félix Fénéon, by its ’insanely hybrid’ creations, we add the Russian painter Kazimir Malevič, whose fame is universally linked to the Black Square on a White Ground (1915), rightly considered one of the seminal works of the early twentieth-century avant-garde. On November 11, 2015, during an international conference organized by the Tret’jakov Gallery in Moscow on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the creation of the Square, a sensational announcement was made that would resonate internationally: extensive scientific analysis actually revealed the presence of two underlying images, consisting of a cube-futurist composition and a second proto-suprematist composition. Added to this is an entirely unexpected final revelation: according to curator Ekaterina Voronina, image analysis revealed an inscription placed by the artist on the Black Square, translatable as “Negroes fighting in a cave,” which would in turn seem to evoke another painting, Combat de nègres dans une cave, pendant la nuit [sic], created, according to the same source, by French writer Alphonse Allais in 1897.

This unmistakable reference to Allais’s monochrome and then, rebound, to that of Paul Bilhaud would, if confirmed, constitute tangible evidence of the porosity of influences between ’major’ and so-called ’minor’ art, as well as of the probable knowledge of the Incoherent Arts movement on the part of exponents of the Russian avant-garde. In support of this thesis, we recall the recent studies of Jean-Claude Lebensztejn pointing out the presence of a mention of the ’Allaisian’ monochrome as early as December 1911 in an article in the Russian journal “Russkoe Slovo.” According to the author, it was, in short, destiny that “in the dynamics of its excesses, the verve of the caricaturists should one day or another meet the radicalism of the avant-garde artists.” Nothing could be easier, then, that a crowd of journalists and other chroniclers of Parisian artistic life spread through various newspapers the nonconformist extravaganzas of the Incoherents. Not only that, these explosive manifestations also spread internationally, projecting their deflagrations all the way to the United States as evidenced by several articles that appeared in 1884 and 1886 in the prestigious “The New York Times.” This is a clear sign of the attention that a movement that for its aesthetic and conceptual innovations largely exceeded the interest of Parisian intellectual circles alone, placing itself in the broader sphere of transnational artistic heritage since the end of the nineteenth century, was the object of. The history of the twentieth-century avant-gardes would confirm this, defining Marcel Duchamp’s monochrome and ready-mades as emblems of modernity that radically challenged - globally - even the very concept of the work of art. This long shadow of the Incoherent Arts, long dismissed because it was considered embarrassing by some, now rediscovers some of its light and forces us to ’observe,’ reconsidering the peremptory judgment we had of it in spite of its ’invisibility.’ For it is clear that some of the works presented to the public as part of the Incoherent Arts exhibitions, particularly Paul Bilhaud’s monochrome and Alphonse Allais’s marquee, bring out a much more complex and ’serious’ subtext than their humorous surface reading. The Combat de nègres pendant la nuit, long imagined as a coarse black blotch encircled by a heavy gilded frame, actually presents an unexpected formal sophistication. A far cry from the evasive and contradictory descriptions given in the many accounts that appeared in the newspapers of the time, the work takes the form of an actual painting consisting of a canvas covered with black paint mounted on a frame. The verso of the painting is closed by two small recessed wooden panels. This extremely singular mounting, totally unprecedented in the manufacturing processes in use, is explained by the presence, evidenced by radiography, of fiber padding placed between the frame panels and the canvas, which gives the painting surface a convex appearance. This ’convexity’ must originally have been significantly more pronounced than it is today, as the padding gradually sagged over time. The atypical technical features of the Combat de nègres pendant la nuit, particularly those of the support, must have had meaning and prompted the viewer to question the symbolic value with which Paul Bilhaud blatantly sought to invest his work. These new elements, which-let us remember-were unimaginable before the painting’s discovery made them analyzable, reveal the decidedly polymorphic character of a painting that several critics have tried to reduce to its mere humorous aspect. [...]

But Paul Bilhaud’s most obvious audacity lies in his willingness to add a strong symbolic charge to this aesthetic treatment. To be clearer, it is essential to recognize that the ’convexity’ of the pictorial surface, induced by the presence of the fiber padding located between the frame panels and the canvas, serves a very specific function. This function, of which the painter is perfectly aware (and how could it be otherwise?), consists in identifying the work not only as a simple ’painting’, but as a ’painting-object’ probably conceived in imitation of an instrument well known to painters, at least since the seventeenth century: we are talking about the so-called ’Claude mirror’. As Arnaud Maillet points out in one of the few comprehensive works dealing with this mysterious accessory, now mostly forgotten, the Claude mirror was distinguished first and foremost by its convexity and dark-colored surface. Generally round, but also found in a variety of shapes and sizes, especially rectangular, it was almost always small and allowed en plein air painters to reflect the surrounding landscape and reproduce it with that somber, golden light characteristic of the paintings of Claude Lorrain (1600-1682). The formal relationships existing between certain types of ’black mirror’ and the Combat de nègres pendant la nuit are manifested through several strongly structuring common elements, which are rectangular shape, slight convexity, and black color. A remarkable specimen of a rectangular Claude mirror, catalogued in the past by the Librairie Alain Brieux and now preserved at the Grasse Municipal Library, perfectly illustrates the multiple correspondences that can be established between this type of mirror and the monochrome of Paul Bilhaud, a learned author who could not have been unaware of the existence of the mysterious instrument. [...]

In a more literary but equally symbolic register, Alphonse Allais also chooses a fiacre curtain for its high potential for suggestion. Emphasized by a title that refers to the universe of prostitution and depraved customs(Des souteneurs encore dans la force de l’âge et le ventre dans l’herbe boivent de l’absinthe) and reinforced by its character as a work on display and thus divorced from its usual context, theobject does not fail to evoke the memory of the famous carriage scene in Madame Bovary in which Emma indulges Léon at length inside the carriage with all the curtains down, a scene that unleashed against Flaubert the wrath of Prosecutor Pinard. As if to better accentuate the work’s Flaubertian reference, Alphonse Allais chooses to replace the yellow of the curtains concealing the two lovers’ dalliances with the color green, symbolically associated with libertinism. This subtle change and quest for suggestive effect probably stands to indicate that Allais intended to amplify the reference to his illustrious predecessor’s text, much as the latter had amplified the erotic power of his scene by concealing the lovers behind the fiacre curtains. Leaving room for interpretative phantasms of all kinds, the incriminated passage from Madame Bovary had not failed to arouse the upset of the imperial lawyer Pinard who, like numerous outraged readers, had identified in it one of the highlights of the immorality of the novel whose general ’color’ he denounced during the trial: “The general color of the work, let me tell you, is that of lust!”. Through the use of green, combined with a support-object deemed suitable to evoke one of the most controversial passages of Flaubert’s novel, Allais symbolically materializes one of the most important moments of a trial still alive in anyone’s memory. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that the company of the Incoherents, populated by numerous men and women of letters, would have so quickly pushed the emblematic affaire Bovary into oblivion. All the more so because Flaubert died in 1880, that is, just two years after the first exhibition of the Incoherent Arts, and that “the enemy Pinard” would leave the scene in 1909, more than fifty years after losing the case and failing to convict the author. Himself a native of Normandy, Alphonse Allais, on the other hand, does not fail to recall his admiration for his illustrious predecessor in one of his most famous texts published in 1895, in which he makes a direct reference to the consapescence of the carriage: “Gustave Flaubert, with his great authority and immense talent, dared not at all insist on what took place in the fiacre of Madame Bovary. I am a bit like Flaubert, so you will know nothing more about it.” A fine statement of brotherhood in the art of subtext. The licentious scene is evoked again indirectly in April 1890 in one of the pages of the magazine “Le Chat Noir,” of which Allais is editor-in-chief. The series of nine vignettes executed by Saint-Maurice, titled Une Tempête dans un fiacre [Storm in a Carriage], shows us two lovers rushing into a horse-drawn carriage, which begins to sway dangerously as a result of their invisible amorous games. As we can see, the tutelary figure of the fumiste Flaubert never ceases to give pause for thought and inspire a generation of artists intent on celebrating and renewing his formidable libertine shamelessness. In the case of Souteneurs encore dans la force de l’âge et le ventre dans l’herbe boivent de l’absinthe, Alphonse Allais deliberately associates the evocation of the fiacre scene with the color green through the use of a consciously finalized title, to which he adds by saturation effect semantic elements that refer to the said color and its meaning. In his study dedicated to it, Michel Pastoureau does not fail to recall its powerful attributes: “[...] the ancient symbolism of green, an unstable, agitated and rebellious color, has always included a certain transgressive and libertarian dimension.” There is no doubt that Alphonse Allais, in his immense transversal culture, was aware of this symbolic apparatus that makes green the color of immorality par excellence. Perfectly aware that the allusive charge of the controversial pigment could help reinforce his intent, he deliberately chose to associate it with the world of prostitution in the title of his work and, by extension, with the emblematic scene of Madame Bovary. The only evidence of ’monocroidal’ work by Alphonse Allais, the fiacre curtain, probably presented out of print in one of the Incoherent Arts exhibitions, finds its place in the form of a synthetic background in his Album primo-avrilesque, published in 1897, which brings together, standardizing them, the author’s ’monocroidal’ experiments.

One cannot help but notice how the rediscovered works of Incoherent Arts turn out, in their full materiality, to conform very little to the image evoked by so many researchers and specialists of the movement over several decades. Their reappearance in the space of observable reality demands, today, a methodical reevaluation based on factual elements.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.