In the vast panorama of the arts between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the singular, and still little-known, figure of Belgian painter Jules van Biesbroeck (Portici, 1873 - Brussels, 1965) represents a significant case for understanding the ways in which classical myth was reinterpreted within the framework of Symbolist and idealist culture in the early twentieth century. A painter and sculptor of Flemish origin, but born in Italy and active between Europe and North Africa, Van Biesbroeck was able to combine aesthetic instances, spiritual tensions and ethical concerns in his work, in a figurative language that moves between academic tradition and modern openings. The BPER Bank Gallery recently brought this artist’s work back to attention with an exhibition, Ferine Creatures. Centaurs, Fauns, Myths in the Work of Jules van Biesbroeck and in the Modern Imaginary, curated by Luciano Rivi (from April 18 to June 29, 2025 in Modena, at the headquarters of La Galleria Bper Banca), dedicated to the Belgian painter’s Symbolist strand, represented in the BPER Group’s collection by a relevant nucleus of no less than 39 works including drawings, paintings and sculptures.

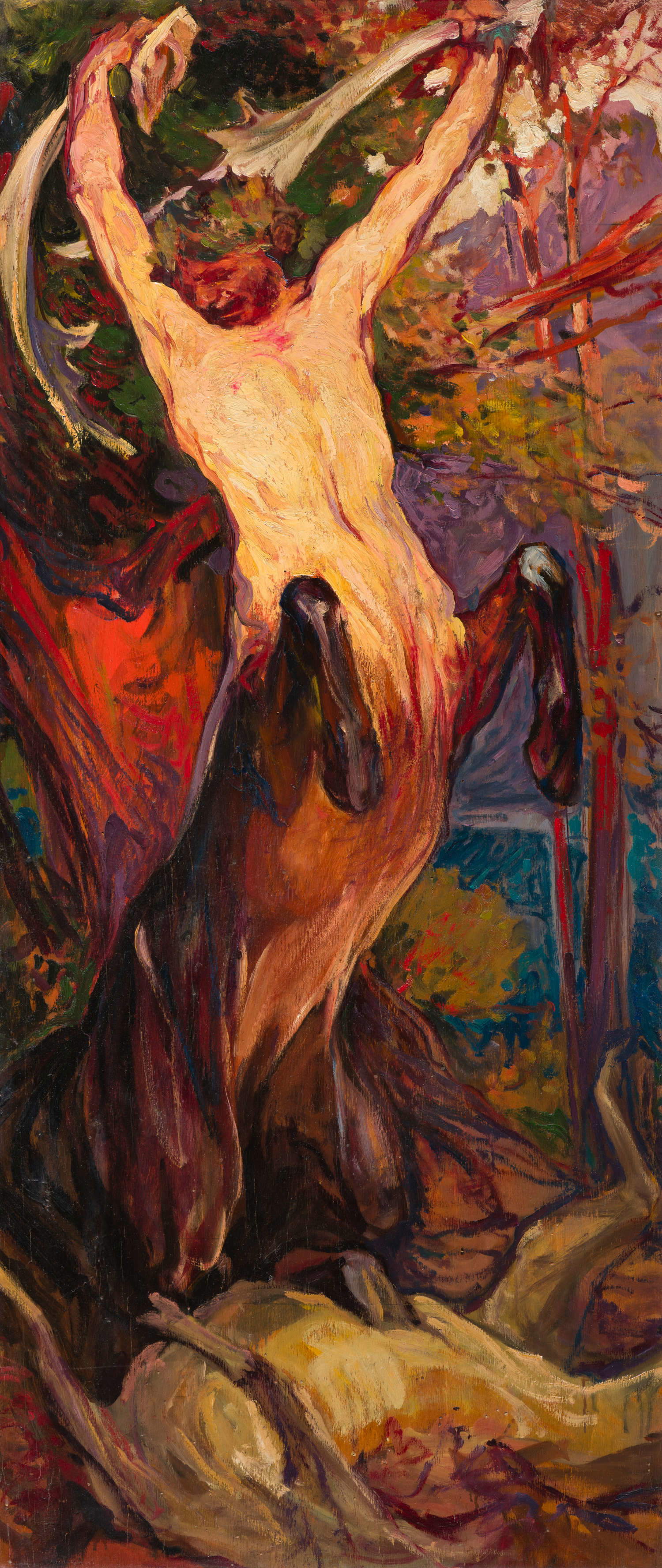

Among his most emblematic subjects is the depiction of the centaur, one of the most symbolically charged mythological images in European culture. Van Biesbroeck’s work, one of the most significant in his oeuvre, which can be dated with good approximation to the years immediately following World War I, depicts the mythological creature in the act of raising in triumph the horns of freshly killed prey, in a pose that combines muscular tension and instinctive assertion. It is a painting that, while drawing on an ancient tradition, speaks directly to modernity: not only because of the themes addressed, but because of the function that myth takes on in a cultural context marked by the crisis of reason and historical disillusionment.

Van Biesbroeck was born in Portici, near Naples, in 1873, the son of a Flemish painter who was passionate about Italy and its artistic culture. His training, from a very young age, was based on drawing and copying, but he developed independently in direct confrontation with the great masters of the past and the artistic ferments of the time. After his first successes in the field of religious and allegorical painting, the artist tried his hand at sculpture, gaining important recognition in Belgium and France. But it is especially in the first thirty years of the twentieth century that his production reaches a recognizable expressive maturity, under the banner of a symbolism that combines spirituality, mythology and reflection on human destiny.

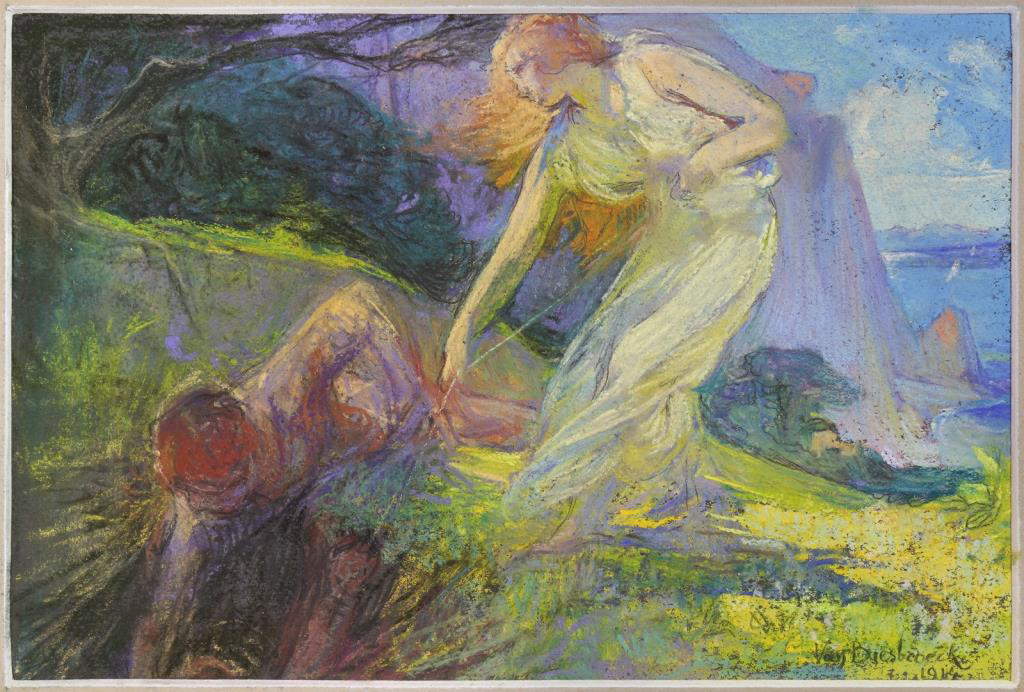

His artistic journey is nourished by a complex imagery: on the one hand, the Protestant religious sensibility of Northern Europe, oriented toward meditation on sin, the fall and the search for grace; on the other, the influence of the Mediterranean landscape and culture, which the artist absorbed during his long stays in Sicily, Capri and Bordighera. Myth, in particular, constitutes for Van Biesbroeck a form of exploration of the human condition in its entirety, through visual allegories that intersect nature, psyche and spirituality.

The choice of the centaur as the subject of one of his best-known paintings is located in this painting. The hybrid figure, halfway between man and animal, has its roots in Greek mythology, but found renewed interest among artists and writers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An emblem of human duplicity - instinct and intellect, nature and culture - the centaur becomes an image charged with ambivalent meanings: it can represent as much a desire for a return to original vitality as it does a threat, a regression to a feral, uncontrolled condition.

In the version proposed by Van Biesbroeck, the element of ferocity prevails. The centaur appears as a figure of panic power, in a scene that visually recalls D’Annunzio’s suggestions contained in the lyric The Death of the Deer contained in the collection Alcyone (1903), but which, compared to the Italian author’s poetics, seems to accentuate the dramatic dimension. D’Annunzio’s poem, itself inspired by other sources, such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses or Maurice Guerin’s novel Le centaure , renders in aesthetic terms the violence of a fight between a centaur and a deer (Il Centauro afferrato avea pei palchi / delle cornae il gran cervo nella zuffa, / come l’man pe’ capei from behind seizes / the foe and draws him, till he tramples him // to the ground to break his back / and the cervix under his heel, / or as in foia the stallion / his mare assails to make her full. // Erto the grasp of the horny mane, / with his two paws he gripped the back / cervine, overtaking it of the torso, / pressing it with all his soma. // Frenzied the deer split / underneath, its eyes upturned, its brown neck / swollen with wrath and bellowing, in every slump / raw scattering to the soil flakes of drool): in the end, it is the centaur who prevails, in a brutal way (the mythological being grabs the deer by its antlers and, splitting it apart, manages to split its skull bones, killing it).

In Van Biesbroeck’s painting, the act of raising the victim’s torn antlers is a gesture that communicates tension, struggle, rather than triumph. Also perhaps weighing on the interpretation of the work is the memory of World War I with its material and spiritual devastation. “We can imagine,” writes Luciano Rivi, "that a few years after the composition of the laude proposed in the collection of Alcyone, let us say to approximate about fifteen, Jules van Biesbroeck, certainly sensitive to Italian cultural production, also found in those verses of D’Annunzio, and together in the rich series of corresponding literary and figurative references from the European sphere, a significant source of inspiration for his painting. The pretext, so to speak, to resurrect that figure that had continued to inspire writers and artists over the centuries. Recent wartime events would push in the direction of an expression of savagery."

The image of the centaur, then, is not to be read as a simple transposition of a mythological subject, but as a symbolic knot connecting different levels of meaning. It is also the result of a widespread cultural orientation among the intellectuals of the time, who recognize in myth a form of resistance to the materialist and positivist worldview. Philosophers such as Nietzsche and Schopenhauer had already indicated the need for a return to an instinctive, Dionysian dimension, as opposed to the cult of abstract rationality. In this view, the centaur is not just a creature of legend, but becomes an epistemological figure: a way of thinking about man in his deepest and most contradictory aspects.

Van Biesbroeck himself shares with many Symbolist artists the idea that art should make itself the bearer of a universal message, capable of evoking mystery, suffering, and the enigma of existence. There is no shortage of biblical references in his works(Adam and Eve, Abel, Samson), but it is especially in Greek myth that the artist finds a more direct and archetypal language. In this sense, the figure of the centaur stands alongside that of the sirens, nymphs, and muses, all recurring presences in his imagery, and often set in Mediterranean landscapes charged with symbolic significance. In Van Biesbroeck’s work, writes Rivi again, there remains “firmly that attitude of attention to reality by way of idealization, intent on tracing the contingencies of the world back to its general principles. Myth, too, with its different figures, would at that point come in handy to better investigate the more general laws of the universe. It was the relationship with nature that was an occasion of deep reflection for Van Biesbroeck. Italy, with its landscapes, would play an important role in this regard. Mediterranean landscapes could easily be transformed into a place of the soul. A memory at the same time of a real and ideal condition, as in an ancient Arcadia, sea and land allowed man to project himself into a dimension of perfect harmony with nature. Reality and myth, that point, could almost coincide.”

When considered in the broader context of its era, the figure of the centaur also appears as a reflection of a modern anthropological condition. Among the most evocative references offered by the cultural debate of the time is a definition by D’Annunzio, who describes contemporary man as “a centaur, crippled and mutilated, who reconstitutes the primitive myth by indissolubly reconnecting his genius to the atrocious energy of nature,” torn between his own technical intelligence and a deep and savage nature. Myth, in this case, is not a refuge, but a way of laying bare the contradictions of the individual, his impossibility of coinciding with himself.

Later reflections of psychoanalysis and existentialist philosophy also move in this direction. Van Biesbroeck’s centaur anticipates in some ways the crisis of twentieth-century identity, the feeling of being composite creatures, subject to divergent drives, poised between rationality and impulse. A figure, then, not only aesthetic but also theoretical, questioning the viewer of the work not only visually but also conceptually.

Although rooted in Symbolist and late nineteenth-century culture, Van Biesbroeck’s centaur also prefigures a reflection that will be taken up during the twentieth century by other languages and other artistic forms. From Surrealism to the poetics of the Metaphysical, the use of mythical figures and bodily hybridizations will continue to express, more or less explicitly, a dissent from modernity and its rationalizing ideologies. In the second half of the century, the centaur may turn into an even more ambivalent figure, contaminated with the machine or synthetic elements, thus becoming emblematic of new tensions related to the body, gender, and identity. But already in Van Biesbroeck’s work, the deep sense of myth is revealed in its ability to hold together ancient instances and modern urgencies. The “bimembre” figure, as he is called, acts as a symbolic intermediary between what man has lost - direct contact with nature - and what he seeks to conquer: a new form of awareness, even a tragic one, of his own condition.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.