All those who, in Milan, visit the Castello Sforzesco, more or less halfway through find themselves, almost suddenly, in a room that is as unusual as it is evocative: above the walls, in fact, the visitor sees intricate foliage of trees and plants growing up to the center of the ceiling, where the Sforza-Este party coat of arms stands out. It does not feel as if one is inside the Falconiera Tower, one of the two square towers of the Castle facing Simplon Park: instead, one has the impression of being under a lush arbor and being immersed in dense but precisely manicured vegetation. This is the Sala delle Asse, perhaps the most famous room in the castle, and it is the work of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519).

To begin to learn about the history of this room, it is possible to start precisely from the coat of arms on the ceiling: for the decoration of the room was commissioned to Leonardo by Ludovico il Moro (Milan, 1452 - Loches, 1508), Duke of Milan, who in 1491 had married Beatrice d’Este, at the time a young girl twenty-three years his junior (an arranged marriage according to the logic of the time, with the aim of consolidating the union between the Sforza and Este families). The duke commissioned Leonardo to paint the “camera grande da le asse,” as we learn from a letter that the ducal chancellor Gualtiero Bescapè sent to Ludovico il Moro himself in April 1498, and the painter, in turn, “promete finirla per tuto Septembre.” The name by which the chancellor refers to the room, “camera grande da le asse,” may be due to the fact that in ancient times the room was lined with large wooden panels, which had a main practical function, namely to insulate the room: the Sala delle Asse is in fact a room facing north, with two walls directly communicating with the outside ... and all of which makes it one of the coldest rooms in the castle. The wooden panels therefore served to make the room more comfortable. The interpretation is favored by the chancellor’s own letter, which lets us know that Leonardo will “desarmarà la Camera grande da le asse,” that is, “disassemble the panels” to work on the decoration. We do not know, however, what the practical function of the room was. The only ceremony that took place in the Sforza period in the Sala delle Asse of which we have record is the assumption of guardianship of the young Gian Galeazzo Sforza by Ludovico il Moro, held in 1480: an important celebration, because through it Ludovico il Moro officially became regent of the duchy (Duke Gian Galeazzo, who would later die in 1494 causing the title to be assumed by the Moor, was still a child at the time). It is therefore likely that the Sala delle Asse was a reception room, or at any rate a room intended for meetings and ceremonies.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Sforza-Este coat of arms, detail of the decorations in the Sala delle Asse (1498; tempera painting on plaster; Milan, Castello Sforzesco). Credit |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Ceiling of the Sala delle Asse (1498; tempera painting on plaster; Milan, Castello Sforzesco) |

What appears to us on the surface to be a simple leafy arbor actually conceals an iconographic program aimed at celebrating the power of Ludovico Sforza and also commemorating Beatrice d’Este, who died in 1497. Scholar Pietro Marani, a leading expert on Leonardo da Vinci’s art, first proposed in 1982 that the sixteen trees painted by the Tuscan artist in the Sala delle Asse be identified with sixteen mulberry plants: the plant’s name in Latin is in fact Morus, a clear reference to the nickname of the Duke of Milan. But that is not all: in fact, the mulberry tree also constitutes a symbolic reference to the duke’s wisdom. In a passage from Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia, a work that Leonardo da Vinci knows well despite having strong gaps in Latin, the author describes the plant in these terms: serotino quaedam germinatu florent maturantque celeriter, sicuti morus, quae novissima urbanarum germinat nec nisi exacto frigore, ob id dicta sapientissima arborum. sed cum coepit, in tantum universa germinatio erumpit, ut una nocte peragatur etiam cum strepitu (“Some plants bloom during germination and mature more quickly: among them is the mulberry tree, which of cultivated plants is the last to sprout, in that it does so only when the cold is over, and for this reason it is called ’the wisest of plants.’ But when it begins to sprout, it does so even in the space of a single night, so much so that it can even be heard making a noise.”) Finally, the mulberry tree is also a reference to the then economic situation of the Duchy of Milan. Indeed, this plant is an important food for the silkworm: as early as 1442 Filippo Maria Visconti, through a decree, had encouraged the establishment of numerous silk factories in the territory of the duchy, in order to be less dependent on imports. Silk production had thus experienced a considerable increase, and in order to meet the needs of the new activities, it was necessary to create mulberry tree cultivations for the breeding of silkworms: the presence of the mulberry tree in the Sala delle Asse was thus also seen as a tribute to the economic productivity of Sforza’s Milan, to which silk production contributed greatly. Again, the fact that the trunks of the mulberry trees take the form of sturdy columns led Marani himself to approximate Leonardo’s trees to the so-called "columns ad tronchonos,“ that is, worked in such a way that they take the form of tree trunks, which characterize a fortunate piece of architecture in fifteenth-century Milan, namely one of the porticoes of the rectory of Sant’Ambrogio, on which Donato Bramante had intervened. So, the mulberry tree thus depicted also celebrates Ludovico il Moro as a ”column" of the Sforza State.

|

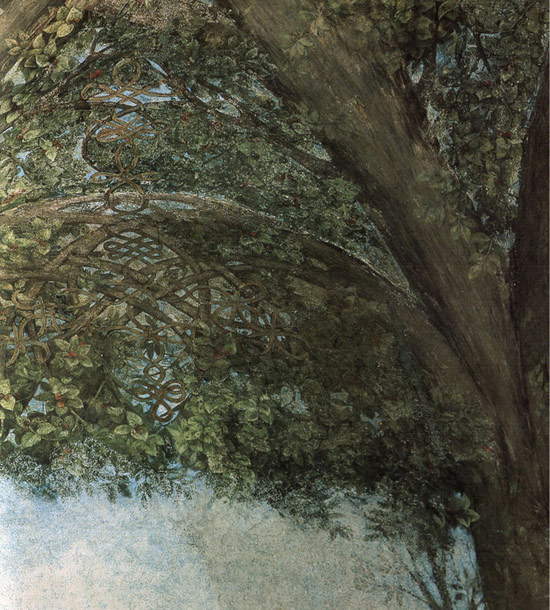

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Mulberry Trees in the Hall of the Axes (1498; tempera painting on plaster; Milan, Castello Sforzesco). Credit |

The mulberry tree, however, is not the only iconographic motif in the Sala delle Asse. Indeed, among the branches we can see intertwined golden ropes: another possible reference to silk production, but also an allusion to the marriage between Ludovico and Beatrice (the knot is in fact a marital symbol). A few more words should be spent, however, on these ropes, which take the form of the so-called"vinciani knots": these are intricate weaves reminiscent of those of the wicker baskets produced in Vinci, the village in which Leonardo was born in 1452 (and whose very name probably refers to the conspicuous presence of wicker willows-in the local parlance vinci or vinchi-in the countryside around the village). They constitute a recurring motif in Leonardo’s art: we find them in several drawings (as if Leonardo enjoyed making these sketches) and also in some works, for example in the Lady of the Ermine. Many have been at pains to find abstruse symbolic references for these entanglements: however, there do not seem to be any reasons other than purely decorative ones (or, at most, from the reference to the sweet vinci of Dante’s memory - Paradiso, XIV, 129 - which imply, precisely, a love bond).

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Details of the decoration of the Sala delle Asse (1498; tempera painting on plaster; Milan, Castello Sforzesco) |

Following the end of the Sforza domination of Milan, the Castle (and with it the Sala delle Asse) experienced a period of unstoppable decay, the effects of which appeared in all their severity when the Italian army, in 1893, ceded the building to the City of Milan. The Castle, over the centuries, had been used as a military fortress but also as a prison, and many of its rooms had undergone heavy alterations: among them, the Sala delle Asse, whitewashed at an unspecified time. And for the Milanese, it was still a symbol of foreign domination: between the end of Sforza rule and the annexation of Lombardy to the Kingdom of Sardinia, France, Spain and Austria had succeeded each other at the helm of Milan. The task of figuring out how to restore the castle falls to an important architect of the time, Luca Beltrami (Milan, 1854 - Rome, 1933), who proposes to restore the entire building and to allocate its spaces to public utilities, such as museums and schools.

The Sala delle Asse was rediscovered in 1893, practically at the beginning of the renovation work, thanks in part to the crucial contribution of German art historian Paul Müller-Walde (Eberswalde, 1858 - Berlin, 1931). Müller-Walde is in the midst of studying Leonardo’s work and learns that there may be paintings by the Tuscan artist in the so-called “dressing rooms” in the northern part of the Castle. Beltrami, thanks in part to the advice provided by Müller-Walde, has the plaster that covered Leonardo’s decorations removed and thus succeeds in unearthing the leafy arbor that the genius of Vinci envisioned for Ludovico il Moro. Some knots still remain to be unraveled about the less than idyllic relations between Beltrami and Müller-Walde (in his writings, the German art historian complains of obstructionism against him, perhaps because other scholars involved in the work did not want the merits of such important discoveries to be attributed to a foreigner), but the fact remains that the paintings resurface and Beltrami orders a restoration that is carried out by the painter Ernesto Rusca.

Given the delicacy of the work, Leonardo’s decorations will undergo other interventions throughout history, the last of which began in 2013 and is still in progress: there was a temporary reopening of the Sala delle Asse duringExpo 2015, while currently the Sala is open but visitors are only allowed to pass through, without the possibility of pausing to take a good look at the paintings. The restoration, entrusted to theOpificio delle Pietre Dure of Florence, has several objectives, as indicated on the website page dedicated to the work: it is a conservative restoration with the aim of “investigating and eliminating the causes of the deterioration of the paintings; identifying through investigations the layers of repainting and the interventions that have occurred over time; and evaluating the possibility of a recovery of the legibility of the decoration while respecting the conservative history of the work.” The Opificio also specifies that “the beginning of the work was preceded by two years of study that also led to some historical news of considerable relevance”: for example, it was discovered that under the Sforza family, the “Sala delle Asse” was known as the “Camera dei Moroni” (where “Moroni” identifies mulberry plants). Works, therefore, of extreme importance for a cornerstone of the production of one of the greatest artists in the history of art.

Reference bibliography

|

| Current restoration site of the Sala delle Asse. Photo distributed under Creative Commons license from fanpage.it. |

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.