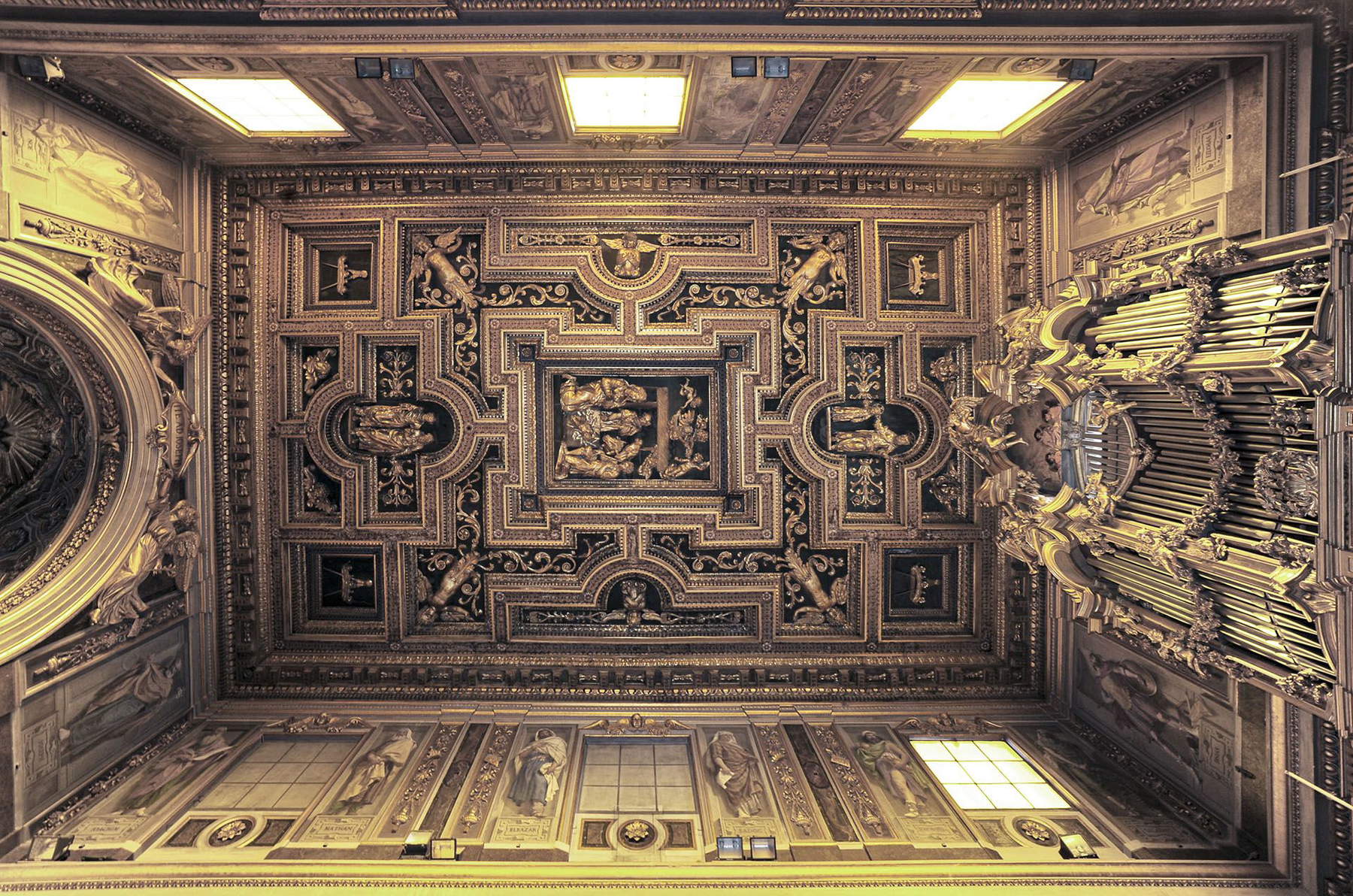

August 30, 2018 the church of San Giuseppe dei Falegnami in Rome, located in the vicinity of the Capitoline Hill, suffered serious damage: as a result of a roof collapse, the building’s splendid seventeenth-century coffered roof fell in, being completely destroyed. A masterpiece in gilded wood with carvings designed by architect and sculptor Giovanni Battista Montano (Milan, 1534 - Rome, 1621) and made around 1611, which the faithful and visitors could admire in all its rich detail along the nave: a Nativity stood out exactly in the center, surrounded by four angels placed at the corners of the central frame, while in the side frames, smaller in size than the previous scene, two other scenes in high relief were visible, depicting St. Joseph with the Child and the Holy Family (the first toward the back wall, the second toward the counter-facade). Standing out above them all, however, was the Nativity, in which the characters appeared under the roof of a hut topped by a chorus of angels with scrolls. On a straw bed was baby Jesus, watched over by Our Lady, St. Joseph, the ox and donkey, and a kneeling shepherd boy.

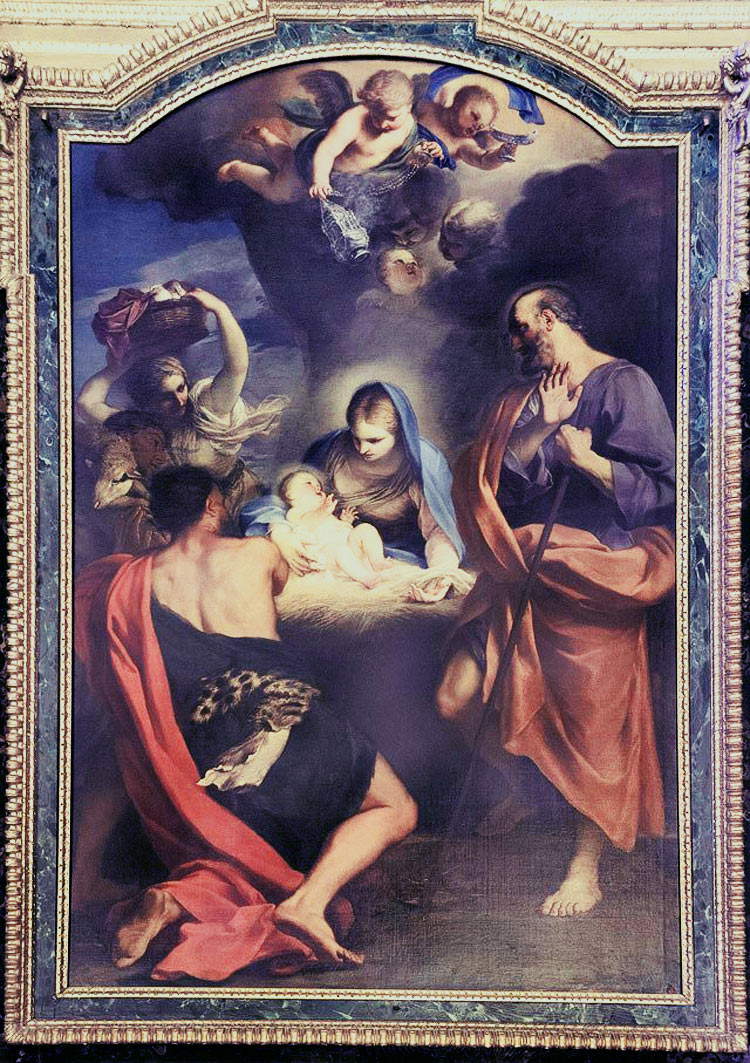

Fortunately and miraculously unharmed, however, was theAdoration of the Shepherds or Nativity by Carlo Maratta (Camerano, 1625 - Rome, 1713), made in 1650 and placed in one of the church’s side chapels. A collapse , however, described as unexpected by the superintendent of Rome himself, Francesco Prosperetti, which could have caused a real tragedy if there had been people inside (fortunately it was closed at the time of the collapse), but with a considerable amount of damage, about one million euros.

The church of San Giuseppe dei Falegnami was built between the end of the 16th century and the middle of the 17th century, designed by the famous architect Giacomo della Porta (Porlezza, 1532 - Rome, 1602). Originally the building was built over the Mamertine Prison, the oldest prison in Rome, located in the Roman Forum. Prominent figures of ancient Rome were imprisoned here: according to tradition, the apostles Peter and Paul spent their last days here before being martyred. Among the most famous figures to be imprisoned here and who died by strangulation or beheading were Jugurthas king of Numidia in 104 BC and Vercingetorix king of the Gauls in 46 BC.

The Confraternity of St. Joseph of the Carpenters, founded in 1499, which later became the Company, had rented in 1540 the church of St. Peter in Prison above the Mamertine Prison to meet and conduct religious services, but it needed a larger and more suitable building. In the last decade of the sixteenth century, therefore, the Company decided to build a new church dedicated to their patron saint St. Joseph, to be erected again on the pre-existing building of St. Peter in Prison, and the project was commissioned, as mentioned, to Giacomo della Porta and Giovanni Battista Montano; thus by the end of 1602 the facade and roof of the building were completed. Upon Montano’s death, the Company appointed Antonio del Grande as its trusted architect to take charge of the completion of the church, and the consecration of the building took place in 1663.

It is therefore an ancient place that is part of the city’s history and that holds within it true artistic and architectural marvels: the coffered ceiling, the paintings, the chapels, and the splendid chancel that inevitably captures the gaze of all visitors. The collapse had destroyed a considerable part of a symbolic place in Rome, a place of worship but also the site of a guild, thus an ancient gathering place. It is thanks to the work and care of the team of restorers that now the church of San Giuseppe dei Falegnami is once again open to visitors to admire its treasures, including the coffered ceiling, which fell ruinously to the ground, making them look up in absolute wonder. Everything was rebuilt respecting the pre-existing one, using earthquake-proof methods to protect the heritage; the restoration of the coffered ceiling and the reconstruction of the missing part were carried out following the most innovative restoration methods, and the reconstructed ceiling maintained the ancient trusses but with more suitable structural solutions. Ten months after the collapse, the construction site was already underway, and last Christmas, in December 2020, almost all of the work was completed: a Christmas present for the entire citizenry. And on March 19, 2021, the day on which St. Joseph is celebrated, the first celebration in the church after the collapse and the restoration site was held with great joy.

As pointed out, Carlo Maratta’s 1650Adoration of the Shepherds or Nativity had been saved from subsidence: a seventeenth-century piece of delicacy, poetry and sweetness that still (fortunately) enchants all who admire it in its chapel. In the center of the scene, the Madonna with the brilliant blue veil encircles the infant Jesus with her right arm, supporting his back, and with the other she raises with refined delicacy on one side the white cloth on which the little one is resting. The infant tenderly gazes at his mother and waves his arms as if to caress her, and from him radiates an intense, warm light that illuminates the composition from the center toward the characters around: St. Joseph on the right of the painting, standing with the typical staff, the shepherds on the left of whom one is in the foreground with his back to her and another, more in the background, carrying a basket on his head. From above, resting on clouds, winged cherubs watch over the scene, watching over and protecting the Child. The scene depicted seems to stop a moment of the holy night: it is in fact a moving scene, anything but static, emphasized by the gestures of the depicted characters themselves, such as the gesture of St. Joseph’s hand that seems very much to want to stop every movement and every gasp, the Child’s little hands, the Madonna who seems to want to lift the fabric to take her son in her arms, the shepherd with the basket is walking and the fabric he is dressed in is being moved, the angels in the sky who are flying and one of the latter is waving a monstrance. These elements are all reminiscent of the original painting of Carlo Maratta, a native of Camerano, a small town in the Marche region near Ancona, who was able to fuse the tradition of classicism and the theatricality of the Baroque: in fact, he is considered one of the last great exponents of seventeenth-century classicism, fascinated nonetheless byBaroque art , especially Romanart , where he himself was very active.

The Nativity of St. Joseph of the Carpenters is often confused with another Nativity that instead derives from thelunette fresco in the first chapel on the right of the church of Sant’Isidoro a Capo le Case or degli Irlandesi, in the Ludovisi district, also in Rome. (In fact, Carlo Maratta painted early in his career the chapel of St. Joseph in the church of Sant’Isidoro between 1651 and 1656 at the behest of the Roman gentleman Flavio Alaleona), The Holy Night preserved in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden. According to some, however, the Dresden painting predates the fresco: however, the three works (that of St. Isidore, that of Dresden, and that of St. Joseph of the Carpenters) appear to be related. The painter, in the period of his training, felt strongly the influence of Raphael, but in particular for that luminism that so characterizes his Nativities he was decisively inspired by the art of Correggio and especially by the suggestion created by theAdoration of the Shepherds, or rather, by the Night, also preserved in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden: among the most beautiful nocturnes in the history of art. Element in common is the baby Jesus cradled in his mother’s arms, who radiates light and becomes the focus of the entire composition, around whom the figures surrounding mother and child, tender winged angels, seem suspended. In the Gospel according to John, Jesus said, “I am the light of the world; whoever follows me will not walk in darkness, but will have the light of life”; a light that appears as early as the birth of the baby Jesus.

The Nativities in the Church of St. Joseph of the Carpenters, namely the one depicted by Maratta and the one in the center of the coffered ceiling, are therefore both now visible in all their glory, saved by a miracle or thanks to the valuable work of restorers. Works that risked being destroyed forever in a place rich in history and tradition.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.