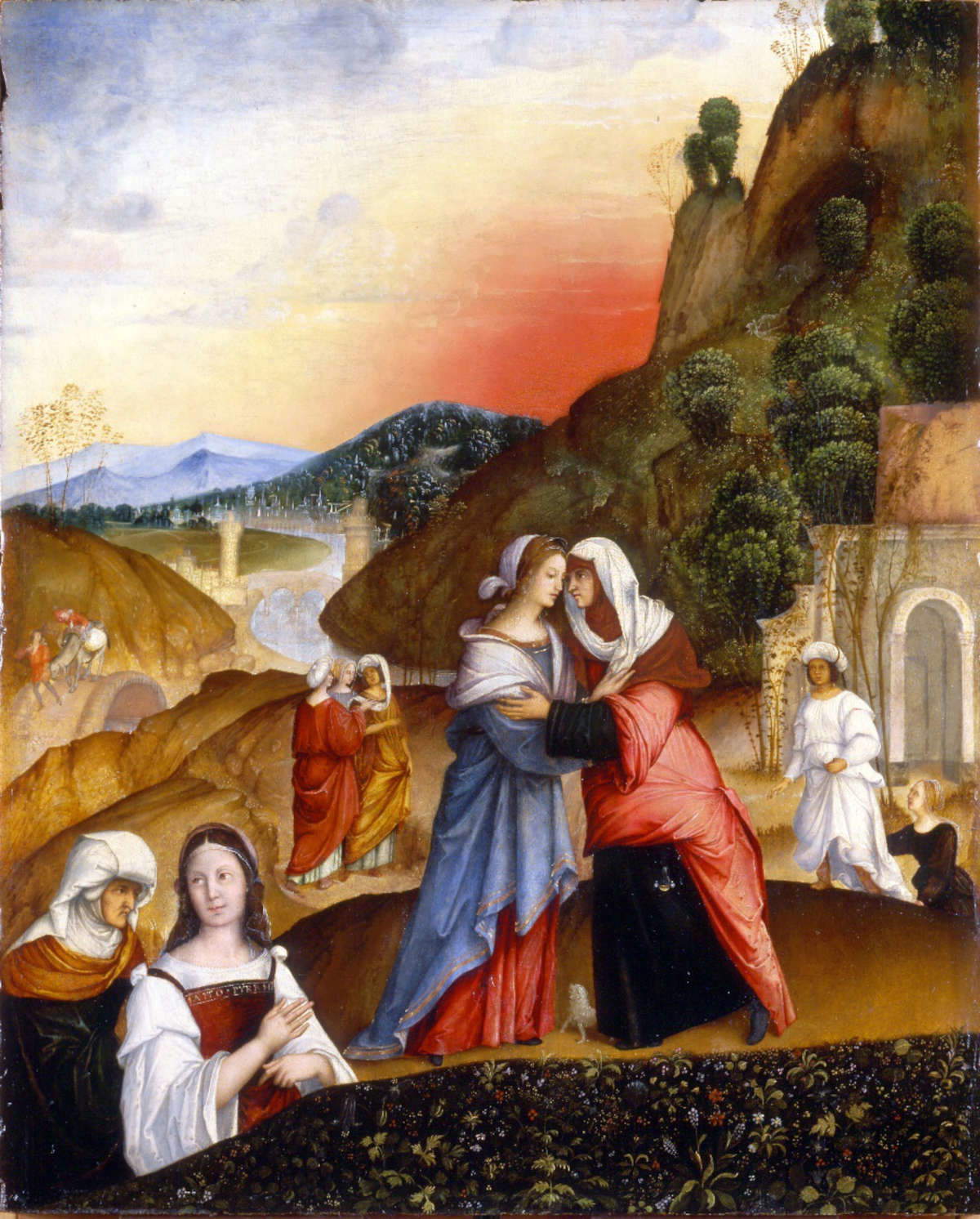

The exhibition The Gift of Art. Donations Acquisitions Restorations 2004-2025 set up at the Pinacoteca Provinciale di Bari “Corrado Iaquinto,” curated by Nicola Zito, until Oct. 10, aims to highlight a specific aspect of the interaction between the museum and its public, that of donations, with the display of a group of works of art donated to the Pinacoteca by artists or their heirs, collectors and representatives of civil society. A painting that only recently, in 2023, entered the institute’s collection thanks to the will of previous owner Anna Maria Macario di Noicattaro and was restored for the occasion, highlighting its extraordinary quality, was chosen for the poster. It is a panel depicting, in the center of a church architecture, a Madonna and Child and St. John, while on the right side an elderly saint - identified as St. Zachariah but to be more consistently identified as St. Joseph, who completes a Holy Family - is intent on a conversation with St. Elizabeth. The critical history of the panel is also relatively recent and particularly striking.

The painting was in fact brought to scholarly attention in 1919 by Mario Salmi, who had identified it in the Macario collection where it was accompanied by an attribution to Raphael. While not blaming the reference to Urbino by virtue of the “gentle motif of the median group, ”1 the historian rejected it, tracing the author instead to a composite Emilia-Romagna sphere, in light of the echoes of the models of Melozzo da Forlì in the architecture, of Ercole de’ Roberti in the “firmness and hardness” of the two saints and of Zaganelli, and of Domenico Panetti in the “lack of relationship between the elongated Virgin and the other figures. ”2 The identity that best synthesized these elements was, for Salmi, that of Antonio Pirri, a Bolognese painter of whom a Visitation and a Saint Sebastian preserved at the Poldi Pezzoli Museum in Milan were then known.

Precisely the similarities between the “slender proportions” of the female figures in the Visitation and the Noicattaro panel and the affinity of the “draperies [...] somewhat hard in the minute, angular folds and almost always guided by threadlike, meandering ribbing,” as well as the attention to “minute details” such as the flowers in the foreground,3 provided the scholar with the stylistic reasons to support the attribution. The main argument, however, seemed to consist in Pirri’s attestation in Naples in 1511, when the painter had estimated the value of a painting by his compatriot Antonio Rimpatta: from the capital to Puglia the step was relatively short. This chronological reference, however, forced Salmi to justify the evident gap with respect to the execution of the panel, which the scholar placed “closer to the middle of the sixteenth century, ”4 with the hypothesis of a prolonged stay of the Bolognese in the Neapolitan city where he could have come into contact with Raphaelesque and Flemish examples.

Almost half a century later, Michele D’Elia5 catalogued the work, redefining its subject in a more generic Sacra Conversazione and resumed the attribution to Pirri; the awkwardness caused by the temporal distance with respect to the known works of the Bolognese led the scholar to recognize in the painting an attempt to “updating on the modern portals of Mannerist culture, from Giulio Romano and Lelio Orsi” by a “late painter, eager for novelty and at the same time unable to grasp its significant values. ”6

Subsequent research on Antonio Pirri has further dismissed the plausibility of the Macario panel belonging to the painter’s catalog. In fact, his production, firmly anchored in the late fifteenth-century Ferrara tradition of de’ Roberti and the early Lorenzo Costa, appears enlivened by openings that do not go beyond the proto-classicist interpretations of Perugino’s models elaborated at the beginning of the new century by the Zaganelli and Marco Palmezzano in the land of Romagna and by Francesco Francia in Bologna7, with a sensitivity to the anticlassical deviations traced by Amico Aspertini8: in short, Pirri’s work is configured as a “pictorial unity” that “is not such as to presage further decisive developments ”9 such as those presupposed by Salmi and D’Elia. In such a homogeneous catalog, all concentrated around the date of 1511, the Milanese Visitation associated not without interpretative forcing with the Apulian Holy Family represents, moreover, in all probability the first issue, placed at the conclusion of an Este-branded formation. That toward the post-Renaissance experiences of Pippi and Orsi thus represents an impossible “quantum” leap for Pirri. As is sometimes the case, however, a prima facie incongruous association may reveal a new avenue of investigation, to explore which, in the absence of information on the painting’s earlier events, it is appropriate to subject the Holy Family to a close stylistic reading.

The first element to strike the eye in the panel is the complexity of the architectural factory that houses it. The central nave of the ecclesiastical environment is punctuated by full-arch bays interspersed with triumphal arches decorated with lacunars and supported by pairs of free-standing columns that are doubled in the aisles, multiplying the viewpoints in a tight perspective progression. This finds a brief respite in a square on which three monumental entrances to a new building open up; the two projecting side ones, the central one of distant Bramante ascendancy elevated and placed in axis with the first basilica body, extending its depth. Here we are faced with a conception whose refined intellectualism surpasses not only Pirri’s antiquarian amusements but also the results of early 16th-century architectural experimentation: the plan and elevations subject to intentional complication those of ecclesiastical factories in the Este area such as Santa Maria in Vado in Ferrara (completed by 1518) and San Prospero in Reggio Emilia (completed in 1527), finding partial comparison only in another’other imaginary construction, that of the fresco that serves as a backdrop to theLast Supper in the refectory of the abbey of San Benedetto in Polirone, whose authorship is still debated between Correggio and Girolamo Bonsignori. The effect of acceleration in depth from the foreground to the background and back again is further accentuated by the geometry of the floor, which is interrupted in the foreground by a stroke of genius illusionistic: Mary sits on a step whose base seems to slide toward the viewer, causing two roses described with Nordic naturalism to fall from it; from the edge protrudes, in tralice, the cruciform staff of St. John.

The figures are enveloped and overpowered by the architecture, appearing so small - down to the miniature scale of the woman holding the child by the hand in the center of the square - that they are in danger of getting lost in the tangle of columns. Accentuating this impression is the subtle agitation that animates the bodies, even those attuned to a placid outpouring of the Virgin with correggesque features who accompanies with her gaze the tender embrace between Jesus and St. John. The direct contact between the two cousins brings to fruition the timid approaches attempted by Correggio in the second decade with the Sacred Families of Pavia, Los Angeles and Orléans, and by Raphael first in the Madonna of Divine Love in Capodimonte and then in the Madonna of the Oak and the Pearl preserved in the Prado, whose models are still the basis of a drawing by Giulio Romano preserved in the Louvre and dated around 152510. The sweetness of affections that unites the group is stiffened, however, by the cold, mental jet of light that isolates it at the center of the nave to reverberate in the flight of columns.

These elements lead one to believe that the painting was made in an Emilian milieu exposed to the influence of Mantua and edified by both Raphael’s models and Correggio’s youthful experiences, in a period circumscribable between the second half of the third decade and the fourth. It is well known how in Parma Allegri himself had helped to spread the new language elaborated in the Vatican decorative sites, but also in Reggio Emilia a privileged channel with Rome was open: Bernardino Zacchetti boasted an alumnuship with Raphael and a collaboration at the Sistine Chapel with his companion Giovanni Trignoli, who maintained close contacts with Michelangelo11.

While betraying some executive naiveté, a possible sign of a juvenile intervention, the Bari panel in any case presents an extraordinary ideational originality, innervated by a vein of restlessness that, excluding a priori Parmigianino, suggests precisely the name of Lelio Orsi, the only artist of the period to present such architectural capabilities as to justify the ambition that inspires the perspectiveexploit. The module of the nave cadenced by round bays covered by lacunar vaults also appears in the central section of a frieze of which a drawing is preserved at the Pierpont Morgan Library, attributed to the Reggio Emilia painter around 156012. On these traces one is tempted to discern in the architectural machination a correlate of the heinous device of the Martyrdom of St. Catherine; in the step in the foreground an anticipation of the inclined plane on which the dead Christ lies between Charity and Justice; in the foreshortened cross of the Baptist a prototype destined to reproduce itself endlessly until it envelops Christ in a mental thicket. The smallness of the human figures in relation to the environment is also a distinguishing feature that differentiates Lelio’s devotional works from the fresco friezes often tuned to a monumental scale.

The main obstacle to be faced in the exploration of such clues is related to the scarcity of references for the period of Orsi’s youth, which have so far prevented a full reconstruction. The earliest known decorative worksite involving the artist around 153513, that of Querciola Castle, cannot offer a conclusive comparison in light of the difference in context and subject matter; it is necessary to limit ourselves to finding asimilar agitation of the “little spirits” to which the anatomical rendering of Michelangelo’s imprint is not sufficient to give concreteness, and an air of kinship that links the putti animating the frieze to the Jesus and St. John of the Bari panel. Posterior to 1540 is the probable dating of what is now considered the earliest movable work in the Reggio Emilia artist’s catalog, the Saint Michael Subduing Satan and Weighing the Souls of the Dead in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, which consummates the achievement of a dynamic balance between Correggio’s grace, which animates the sinuous poses of the figures, and Pippi’s expressive violence emanating from the gaping mouth of the Inferno. Elements of affinity with the Bari painting can be detected here in the ease of representation, the reduced scale of the characters compared to the surface of the canvas, and the chromatic direction that favors dark tones and shadows, brightening them with sudden jets of cold light.

The decidedly fainter resonance that echoes of the post-Raphaelesque language elaborated by Giulio Romano at the Gonzaga court find in the Holy Family than in the English panel induces us to go backwards into a period adjacent to that of the Querciola decorative site, in which the Novellara painter is attested by documents in the nearby city of Reggio. The only reference, little considered by critics, that runs to our aid is The Elemosina di Sant’Omobono depicted on the predella of the altarpiece dedicated to the Cremonese saint executed for the church of San Prospero by Bernardino Zacchetti’s most important pupil, Nicolò Patarazzi (1495-post 1552), between 1530 and 1535.

The contrast between the monumental and compassed main image, of strict Michelangelo and Raphaelesque observance, and the “unusual liveliness” of the predella14 had led Massimo Pirondini to speculate on an intervention by Lelio, in advance of the “unbridled fantasies” of Querciola,15 corroborated by the young artist’s collaboration with the mature master in the decoration of a triumphal arch erected in 1536 on the occasion of Ercole II Este’s entry into the city16. Against the backdrop of a colonnade, amid men and especially women with simplified physiognomic features akin to those of Mary and Elizabeth in the Holy Family who crowd together madly in what looks more like a popular upheaval than an orderly distribution of alms, rubicund and curly-haired putti like the Baby Jesus and the St. John appear. In contrast, the St. Omobono on the right appears to be a cursive transcription, bordering on parody, of the austere one that towers in the center of the main compartment and lends itself to close comparison with the Joseph of the Bari panel. The almost damp draperies furrowed by thick folds are also close to those of the painting from Noicattaro. A certain executive clumsiness in the anatomies only emphasizes the freedom and eagerness of the composition, closer to the “terrible” scenes left by Pordenone in Cremona Cathedral than to the classical choreographies set up by Giulio Romano at Palazzo Te, opposing a rejection tinged with irreverence to the static firmness of the altarpiece.

Extending the comparison to Patarazzi’s only dated altarpiece, the Noli me tangere commissioned in 1538 for the church of Santa Maria del Popolo and now housed in the Civic Museums, the narrative episodes of almost miniature taste of the two nuns on their way and the two Marys received into the Sepulchre by the Angel, which appear to be by the same painter’s hand, seem to be intended to reintegrate in an urbane way the impetuous provocation of the predella of St. Omobono. It is difficult, moreover, not to detect similarities between these inserts and those of the mother with child in the background of the Holy Family and the foreshortened cross in the foreground of the panel as in the Sepulcher of the altarpiece. Such cross-references suggest the possibility that Lelio, having been exposed at a young age to the Reggio Emilia master’s palatial classicism and having reacted to it in theElemosina, had ended up temporarily infecting him with his narrative verve . This was at least before Patarazzi went in the 1940s “more and more tightening in defense within formulas of by now old invention ”17 so much so that he still took up Raphael’s Madonna of Divine Love, then owned by Leonello da Carpi of Meldola, in the Madonna and Child, St. Anne and St. Cola now at the Pinacoteca Fontanesi18 around mid-century. The sculptural material of the master’s works, on the other hand, may be imputed to the hardness that characterizes the figurines of Joseph and Elizabeth in the Bari panel and that Salmi had associated with the models of Ercole de’ Roberti19.

On this basis, the attribution to Lelio Orsi gains substance to the point of supporting an attempt to scan the painter’s early figures in time. In the still open doubt about the artist’s year of birth (between 1511 handed down by tradition and 1508 deduced from documents20), it is permissible to assume that the predella of Sant’Omobono, executed in aid of Nicolò Patarazzi, constitutes the earliest known work and can be placed around 1533, between the placement of Correggio’s Night in the Pratonieri chapel in San Prospero in 1530 and that of Michelangelo Anselmi’s updated Baptism of Christ in the Panciroli chapel in 1534 or 1535. As suggested by Pirondini, theElemosina would make a trailer for Querciola’s expressionistic friezes, inspired by Pordenone’s “popular theater” in Cremona and the last reverberations of the grotesque culture propagated by Leonbruno in Mantua even before Giulio Romano’s inventions. The Holy Family already Macarius, which testifies to greater compositional maturity, may follow the castle decorations by a little, placing it close to the collaboration on the triumphal arch for Hercules II, the first public commission recorded in the documents.

The observation incidentally proposed by D’Elia in an attempt to hold together data that are too distant from each other, those concerning Antonio Pirri and Lelio Orsi, is thus shown to be revealing by drawing an impossible but suggestive analogy between two original and only apparently marginal interpreters of their own time.

1 Mario Salmi, Appunti per la storia della pittura in Puglia, L’Arte, XXII (1919), p. 175.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid, p. 176.

4 Ibid.

5 Michele D’Elia, Mostra dell’Arte in Puglia dal tardo Antico al Rococò: catalogo, Bari, Pinacoteca Provinciale, July 19-December 31, 1964, Rome, Istituto Grafico Tiberino, 1964, p. 110.

6 Ibid.

7 Giuliano Briganti, ed, La pittura in Italia. Il Cinquecento, Milan, Electa, 1988, vol. 2, p. 806.

8 Mauro Natale, Antonio Pirri, The Visitation, in Museo Poldi Pezzoli. Dipinti, edited by Joyce Brusa, Alessandra Mottola Molfino and Mauro Natale, Milan, Electa, 1989, p. 129; Pietro Di Natale, Antonio Pirri, Presentazione di Gesù al Tempio, card 19, in Rinascimento a Ferrara: Ercole de’ Roberti e Lorenzo Costa, edited by Vittorio Sgarbi and Michele Danieli, exhibition catalog, Ferrara, Palazzo dei Diamanti, February 18-June 19, 2023, Cinisello Balsamo, Silvana Editoriale, 2023, p. 140.

9 Briganti, 1988.

10 Roberta Serra, Madonna, the Child and Saint John between Saints Paul and Mary Magdalene in adoration, in Giulio Romano in Mantova. “Con nuova e stravagante maniera,” exhibition catalog, October 6, 2019-January 6, 2020, Mantua, Palazzo Ducale, edited by Laura Angelucci, Roberta Serra, Peter Assmann, Paolo Bertelli, 2019, Milan, Skira, p. 134.

11 Massimo Pirondini, Painting in the Sixteenth Century in Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Credito Emiliano, 1985, pp. 99-100.

13NoraClerici Bagozzi, Frieze with putti, satyrs, horses, warriors, monstrous animals and coats of arms, card 1, in Lelio Orsi, edited by Elio Monducci and Massimo Pirondini, Reggio Emilia, Credito Emiliano, 1987, pp. 40-43.

14 Pirondini, 1985, p. 127.

15 Ibid, p. 30.

16 Ibid, p. 127.

17 Ibid, p. 35.

18 Pirondini, 1985, p. 129.

19 M. Salmi, 1919, p. 176.

20 Massimo Pirondini, La vita e l’ambiente, in AAVV, Lelio Orsi, Credito Emiliano, Reggio Emilia, p. 21.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.