Silvia Vendramel (Treviso, 1972), an artist who works mainly with sculpture and installation, proposes research based on the transformation of the everyday and the elaboration of her own feeling, in constant dialogue with the reality that surrounds her. She lives and works in the Ligurian hills on the border between Italy and France. A graduate of the Villa Arson, Nice in 1996, in 2021 she was among the artists invited to the design of a monument “A sculpture for Margherita Hack,” she created with Beatrice Meoni the project Pratiche di scambi based on the dialogue between different and at times converging artistic practices, and in a similar vein for about three years she collaborated with Beatrice Meoni, Philippa Peckham, Maja Thommen and Elena Carozzi. She has exhibited her work in several galleries and museums. And she tells us about her art in this conversation with Gabriele Landi.

GL: Silvia, I wanted to ask you, to begin this conversation of ours, about the golden age of childhood by asking if for you, as is the case for many, it was during this period of your life that you unknowingly began your journey on the path of art. What were the episodes, people, facts objects and or encounters that led you down this path? Do you recount?

SV: “I think I was really little, I remember the slightest sound of pencil on paper with the exhilaration of an unwrapping package, I stood to his left and followed his hand as the sound caressed me, it was mine.” I repost this long ago writing about a thrill I felt as a child watching my father draw for me on his way home from work. Art has always been a source of strong emotions, a kind of repeated falling in love that then ignited my curiosity to go deeper and deeper to unearth the origin of it all: the recipe of how to do it, how to reach that silent essence that art moves. The episodes and encounters have been many, since I was a child I saw biennials and exhibitions, and artist friends often came home; what has stuck with me most are short caustic phrases, seemingly unimportant words that remained to ripen in me until they were understood well afterwards. The artist sows doubt in the child. Artists’ words are important, and you, Gabriel, know this. Among the exhibitions I remember most vividly is my encounter with Fausto Melotti’s work on the ground floor of the Palazzo Fortuny in Venice, I was about fifteen years old and a little later I later I remember being pinned in front of a Jean-Michel Basquiat in a gallery in Salzburg, the painting was hanging in the back offices and the gallerists invited me in, I think they laughed themselves silly seeing my eyes glazed over and glistening! Ditto a decade later at the Arco fair in Madrid, in front of a work by Doris Salcedo, there I was already grown up, determined to be an artist, my head shaved and tears in front of a piece of furniture embedded in concrete.

What studies did you do?

After attending the Liceo Artistico in Treviso, I enrolled at EPIAR in Nice (École Pilote Internationale d’Art de Recherche, Villa Arson): it’s an art school within an exhibition center that organizes art residencies in parallel. At the time, artists such as Franz West, Martin Kippenberger, Paul McCarthy and many others were invited, and for a young person, misogyny aside, it was interesting to be confronted with such an active artistic environment. It is a center with a conceptual matrix, at that time it was video that was all the rage, mine was a position that was not really in accordance with the trend there, what interested me was the fact that you were not required to choose a direction and that you could have experiences with various media depending on the project: that was the reason why I enrolled there and not in Venice, which in the early 1990s was completely abandoned. In ’94 I took part in a drawing course at the Ratti Foundation held by Markus Luperz and Gérard Titus-Carmel: the Foundation’s proposal was to invite two artists with opposite tendencies and have them intervene separately, we spent about three weeks drawing from morning to night, inside a church with guys who came from all over Europe, it was beautiful. There I met a friend who was studying sculpture in Carrara, so I began to frequent the city and observe all those traditional techniques that were banned here.

In Carrara did you enroll in the Academy or did you go attracted to sculpture?

No, the Academy did not interest me, I was interested in learning how to work with plaster and I was interested in molding, that is, making casts and using silicone. I used to go to Carrara for short periods and watch friends grappling with all those techniques that we didn’t learn at home; then, at Studio Nicoli, Louise Bourgeois was having her pieces made in marble so I would go and peek at the preview works!

Quite a privilege! Did you ever meet her in person?

Yes, I met her in her Chelsea home in New York in 2008, I was there for the New York Prize she won in 2007, I knew it was possible to attend her Sundays where she received artists who wanted to talk about their work: it was exciting, she was already very old and died a few years later. She lived in a typical American house with steps of only a few steps. The most battered was hers, inside it was like her grandmother’s house, full of old posters and playbills from a lifetime of exhibitions, then there was a small living room with her and her assistant ready to receive us, a low table full of all kinds of alcohol and drinks, she drank Coca-Cola with a straw from a can inside a tin cup (I later dedicated a portrait to her). We were four female artists from different countries, she listened attentively and occasionally said “c’est ça, c’est ça, right!” I remember when she exhibited at the Prada Foundation in Milan, when the Foundation still had a “small” downtown location, I showed up at the opening with a rose, but she was not there, the artist was not present. I also loved her very much for her shy and outspoken character.

In Carrara after these spot presences you decided to stop: what attracted you?

I returned to Carrara and made my home there about 20 years later, attracted by a certain genuineness of the people who live there that, in my opinion, comes from a love of a craft handed down from generation to generation: a deep knowledge of sculpture and its techniques. Carrara is a place that has always been accustomed to receiving outsiders in search of material and inspiration. Now, unfortunately, the town suffers from medieval management and barely survives amidst omertà and a failure to adapt to the demands of the unscrupulous times in which we live. When I discovered it I was about 20 years old, and I must say that for me, coming from the Veneto via France, Carrara served to discover an Italy I did not know.

Did you establish relationships with other artists in Carrara?

Of course, in the fifteen years I spent there I changed several studios, and the meetings, exhibitions and collaborations were many.

With whom did you forge the strongest bonds?

Friendship between artists is not an easy thing, you know: perhaps one of the saddest aspects of friendship, even more so than love as far as I am concerned, is that it can run out, you have to know how to take advantage of it as the most beautiful gift. The course of life, commitments, career, change of role can be fatal and dissipate what, for a time, was a great understanding. In this regard, I found Martin McDonagh’s film The Spirits of the Island upsetting, precisely because it brings to light what I perceived as taboo: the admission of no longer being able to stand the person to whom we have been connected, accepting change, cutting, tearing away. Among my closest ties is Fabrizio Prevedello, a friend, with him I feel at home, we share choices and lifestyle, exchanges in the studio, criticism out of the teeth and long discussions have lasted for years now. After all, friendship is also a matter of time, we mirror each other by reminding each other of who we are and have been. Another intense bond arose from our collaboration with artists Elena Carozzi, Beatrice Meoni, Phillippa Peckham and Maja Thommen. For about two years we collaborated assiduously by attending each other’s studios as a group, observing each other’s work, raising questions and requests, and shaping various projects. Conscious of desiring an exchange between women artists, the attempt was to experience the closeness of absolutely distant languages while keeping alive the sharing of research and suppressing authorship. Silvana Vassallo of Passaggi Arte Contemporanea gallery and curator Ilaria Mariotti were both attentive supporters of the project and then became over time, friends.

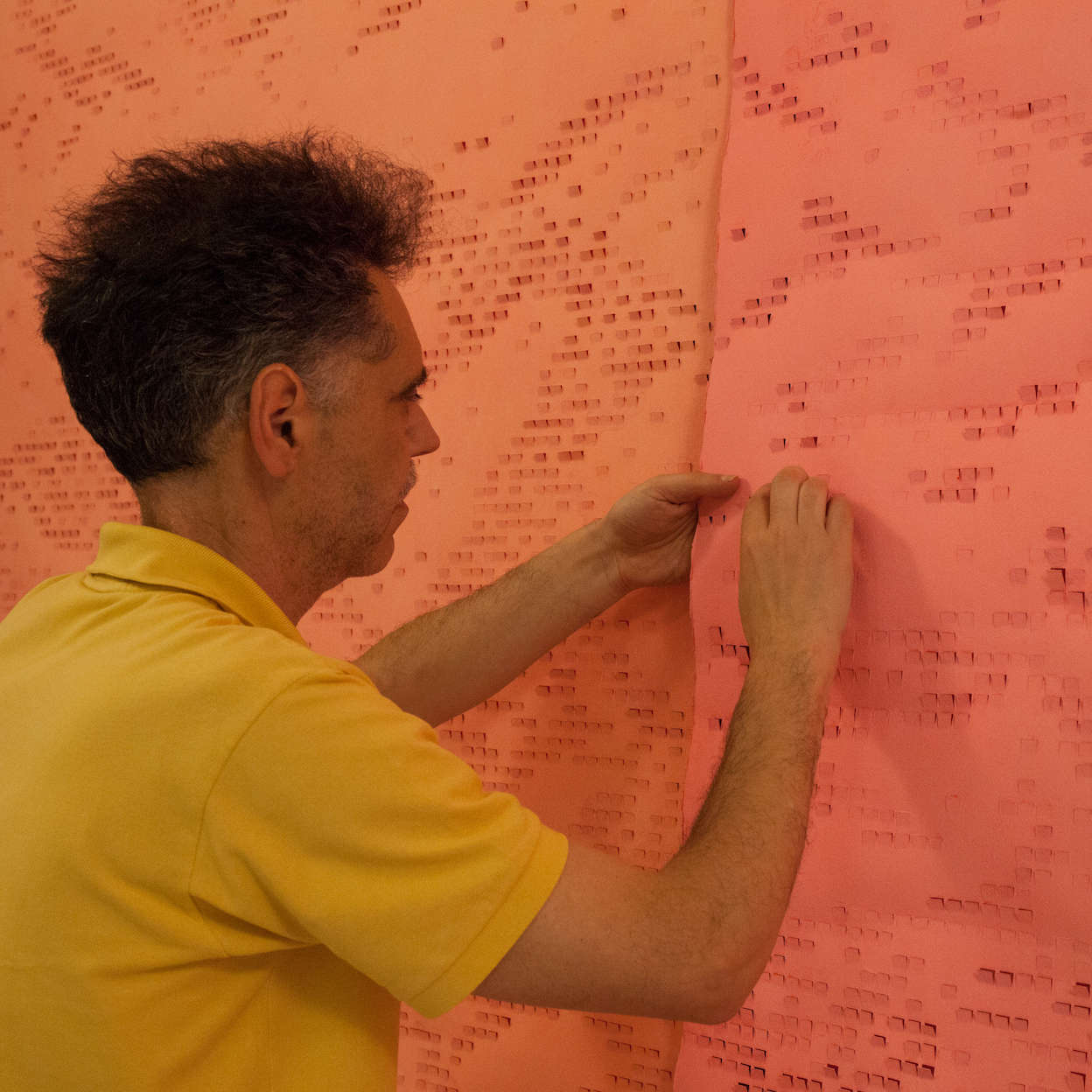

What trigger dynamic did you follow to activate this collaboration on the level of material work?

It all started from an interest in the studio, from that very special place where thought takes shape. What interested us most was to observe the stages of elaboration of the work, to share the doubts and possibilities that arise as the language takes shape. In a spontaneous way there arose a desire to make certain suggestions of the other’s own as if responding to a call. Rarely was it a matter of working with four or more hands, but rather of making the transition between the different voices smooth; the point was to shift one’s center of gravity toward the other in the search for a new balance, it was good to listen, to step outside one’s own interests to encounter new and unexpected ones, it was a real willingness to step outside one’s own center, a delicate operation that required acceptance and care for the other and a certain courage to respect one’s own autonomy. These experiments gave rise to several experiences, including an early exhibition entitled Between the Studio and Later Attention is Novissimo Fabric. In the first one, at the invitation of Enrico Formica at the Liceo Artistico in LaSpezia, we invited students to participate in the setting up of the exhibition; we wanted the students to participate in our discussions with respect to what happens during an exhibition. In the other one, a few years later at Villa Pacchiani and curated by Ilaria Mariotti, the rooms were inhabited by works elaborated over time and born from the same instances I told you about. The project then continued with the sole collaboration with Beatrice Meoni titled Practices of Exchange.

How did the high school students react to your solicitations?

I think the boys were initially intimidated since we were basically the age of their mothers but for us this was an interesting fact because it could show them a greater variety of female role models. We talked about proximity and relationship to the space and little actions were done, for example, while they were grouping, we were getting a little too close to them, initially creating some discomfort that could be useful to understand what happens in an exhibition when certain sensitive strings are being pulled, when in order to observe and enter the work we have to get closer and further away, basic concepts but in my opinion important to go beyond a superficial look.

I am interested in this idea of inhabiting a place I feel in it the vital throb of your breaths, the glass that through the energy of the breath, which dilates it, inhabits a place vitalizing it. What is the idea behind these works?

The idea behind the cycle of works entitled Soffi is the sense of belonging and its contradictions, it is a direct confrontation between a kind of cage and the glassy mass that within it makes space by adapting to the imposed constraints. Formally I start from family objects made of metal, decorative, often prissy objects, which I use to shape empty spaces inside which I make glass blow to the limit of collapse.

Are you interested in the mnemonic dimension that these objects carry?

These works arise from a reaction to a mood of impatience, the process that generates them gives me a way to formally process the starting feeling in order to transform it and go beyond it. Memory, to which the objects I choose are witnesses, is a component of the work along with other elements, but the sculpture in its making acts in an almost autonomous form transforming object and content.

Where did you start making these works?

When the desire to use glass first arose, I was lucky enough to meet a craftsman who had a workshop on top of a hill in the province of Pisa, a young American in love with glassblowing who made the work completely independently, Isack Listad, an unparalleled companion. Most of the pieces I made with him.

Did the idea of using glass come from an awareness of a tradition linked to your origins?

I would say no, I was born in Treviso, but I don’t think the choice of glass has anything to do with my origins; the first piece I made was a wrought-iron centerpiece with a scarlet red glass container inside. One day, rummaging in the attic, I found the metal frame, the glass part of which had been lost, it was an object that had been part of my childhood, the vine shoot simulated in metal appeared to me as an artery, and I felt the desire to fill its void.

How important is the objet trouvé in your work?

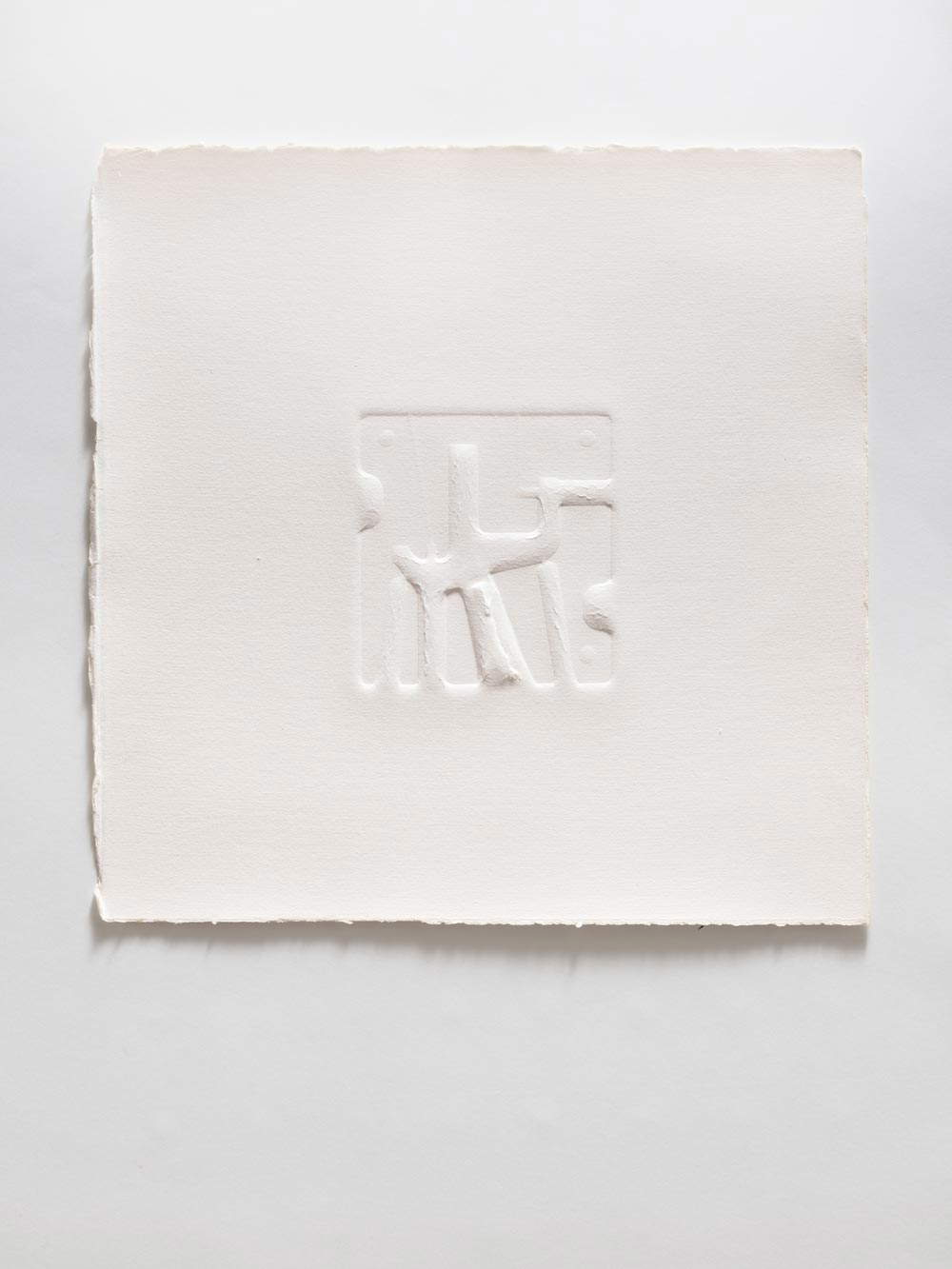

I think many will agree with me in saying that Duchamp has helped to masterfully undermine the landscape of creativity by continuing, after more than a century, to give us some nice headaches with respect to originality. Objects for artists, from Duchamp onward, are tools of analysis, they are means to tell about human beings, their foibles and contradictions. What fascinates me about objects is their history, what they express through the traces they bear, the narrative they suggest. When I choose a material or an artifact I try to exercise a transformation so that the object maintains its identity but is slightly shifted from it, there is a formal and visual ambiguity that I am interested in activating in order to awaken a kind of inner gaze. Last summer I took part in a residency at the former Faro toy factory (Sensitive Cartography 2022/ Cars Omegna) and visiting the archive I found metal casts dating back to the early postwar period that were used to make aluminum toy parts. They were graphically very interesting objects, hollows and the back of some of them were knurled, and I did not understand why: they were tank parts that had been recycled, since it was difficult to find available iron at that time. Here in one artifact already could be read at least two significant stories and I wanted to follow up the story so I decided to print them on paper giving shape to very light bas-reliefs, in this way the object undergoes manipulation so it continues to exist in a new form. To answer your question, objet trouvé in its historical definition does not interest me because it is tied to a purely conceptual language that does not belong to me.

In fact, I too believe that the question of the objet trouvé since Duchamp’s time has become considerably complicated and that the conceptual dimension alone represents only one of the many aspects of the question. So the question becomes this: in your eyes, does the dimension of the landfill understood as a storehouse of forms, stories, and ideas have any appeal?

In my opinion it all depends on the quality of the work, the intensity with which it is created, there is a certain vibration that resonates in certain works, a certain unmistakable truth, the rest is misunderstanding, conformity, banality. To return to my relationship with objects, I would like to tell you about an installation entitled Di qualcosa il fondo, per qualcosa il coperchio, composed a work in compressed sand, the form of which is obtained by filling a mini-bath tub (semi-cup). In size and volume, the upside-down tub harks back to certain medium-sized Etruscan sarcophagi. One day walking in Carrara, while a move was in progress, I saw this tub loaded onto an Ape car, upside down and at eye level. Beautiful, quiet, with its history of baths taken and taken again, with its surface torn from tiles and its massive sinuosity designed to accommodate the body, it seemed perfect! Etruscan sarcophagi and their secrets hidden inside were the founders of great modern sculpture starting with Henry Moore, and all these aspects put together ignited in me a desire to shape a vision. Again it was about transformation, finding ways to bring the mystery to life. The technique of compressed sand is used in foundry to fill the inner void in forms, these voids are called souls. The soul has the characteristic of being solid and compact but easily shattered, this vulnerability of the material along with the reference to games by the sea, seemed to me to accord with my project: life, play and death compacted into a single presence. The installation was part of the solo exhibition At the Same Time at Teké Gallery in Carrara and placed in the basement of the old store turned gallery. The gallery team bent over backwards to keep up with my needs, rethinking the interior spaces to accommodate the entire project that expanded throughout the interior spaces and 14 storefronts. Also at the Blu Corner in Carrara, another strongly connoted exhibition space and home of the gallery run by Nicola Ricci, I exhibited some compressed sand pieces entitled Without Too Much Noise. In the years spent in Carrara, the exhibitions at Blu Corner have been numerous and undoubtedly the most significant was the solo show Soffi e altre stanze where, also on that occasion, I intervened in the beautiful outdoor windows. All this is to tell you about your places, Gabriele, which have also been mine and to give you an idea of the relationship I establish with the objects I seek out and encounter.

The author of this article: Gabriele Landi

Gabriele Landi (Schaerbeek, Belgio, 1971), è un artista che lavora da tempo su una raffinata ricerca che indaga le forme dell'astrazione geometrica, sempre però con richiami alla realtà che lo circonda. Si occupa inoltre di didattica dell'arte moderna e contemporanea. Ha creato un format, Parola d'Artista, attraverso il quale approfondisce, con interviste e focus, il lavoro di suoi colleghi artisti e di critici. Diplomato all'Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, vive e lavora in provincia di La Spezia.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.