In the Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, André Breton, the founder of Surrealism, summarized the formal practice of the movement under a chapter with a very indicative title: Secrets de l’art magique surréaliste, or “Secrets of Surrealist Magical Art.” Breton, a poet and art critic, established pointers for Surrealist writers, but the discourse can be extended to the visual arts as well: “Have something brought to you to write, having settled down in a place that is as conducive as possible to the concentration of your mind on itself. Put yourself in the most passive or receptive state you can. Ignore your own genius and talents and those of everyone else. Tell yourself that literature is one of the saddest paths to anything. Write quickly without a preconceived argument, fast enough that you won’t hold back and won’t be tempted to read again. The first sentence will come by itself, because it is true that every second there is a foreign sentence just begging to be externalized [...] Continue as long as you like. Rely on the inexhaustible character of the murmur.” Breton defined Surrealism as a “pure psychic automatism” through which “it proposes to express, whether verbally, in writing, or by other means, the real functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, outside of any aesthetic or moral concern.” It can be understood, then, why for Breton surrealism (and in particular surrealist practice) had a magical character, and the presence of magic andalchemy, in addition to being frequently present in the art of the surrealists, are of decisive importance for the very concept of “surrealism”: on the one hand, magic helped to form the ideas underlying the movement, and on the other it constituted a fundamental repertoire and also directed some of the developments of surrealism.

The theme of the relationship between surrealism and magic was addressed extensively for the first time in Europe in the exhibition entitled Surrealism and Magic. Enchanted Modernity (Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, from April 9 to September 26, 2022), curated by Gražina Subelytė, and organized in collaboration with the Barberini Museum in Potsdam (site of the second stage of the exhibition, from October 22, 2022 to January 29, 2023). The birth of Surrealism, as anticipated, is formalized with the first manifesto of 1924: at the time, the city of Paris, the place where Surrealism was born, was experiencing (and this was at least since the end of the 19th century) a strong interest inesotericism and theoccult (the historical moment was effectively documented in 2018 by the exhibition Art and Magic held in Rovigo) in response to the development of industrialization, positivism, and the dominance of technology. It was, in some ways, a legacy rooted in Romanticism and what Francesco Parisi has called the “myth of protest against the social order and rationalistic-industrial power.” Esotericism as counterculture, then: and the Surrealists are identified by Subelytė as the last heirs of this trend “which proposes,” the scholar writes, “a critique of the sterile materialism of rationalizing modernity without recourse to institutionalized religion.”

To gain an impactful understanding of how a part of the Surrealist movement saw itself, it may be interesting to look at a famous work by Romanian painter Victor Brauner (Piatra Neam�?, 1903 - Paris, 1966), despite the fact that it was produced more than two decades after Breton’s manifesto and when by then the movement had begun to lose its bite: it is The Surrealist from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, in which the artist is presented as a magician, an alchemist capable of mastering the four elements, according to imagery that Brauner derives from tarot cards and in particular from the figure of the juggler, who becomes a symbol of the Surrealist’s creativity. Magic is of interest to the Surrealists because the Surrealists move away from rational thought, and magic therefore offers a kind of method, a way to understand and transform reality apart from the use of reason.

Then there are additional reasons that support the Surrealist movement’s interest in magic. Surrealism, writes Daniel Zamani, believed in the “possibilities of a total change in individual and collective consciousness and, by extension, in society” in the aftermath of the tragedy of World War I. In order to effect this change, Breton emphasized, a revolution in mentality, passing through the imaginative and the irrational, would be necessary. In this sense, Zamani continued, “the Surrealists’ exploration of magic and the occult is a corollary of their ambition to reconfigure Western society, as well as a key ingredient of their hoped-for new utopia.” For the Surrealists, then, interest in magic, the occult and the esoteric has nothing to do with issues of the supernatural, but is strongly anchored in reality and the desire to change it. Freeing reality from the imposed constraints of reason: this, one might say, is the first point of the Surrealist program.

There are many references to practices of the occult and magic in the Surrealists’ texts and programmatic statements. Among Breton’s pages one finds many, starting with those to the fourteenth-century French alchemist Nicolas Flamel, linked to the search for the philosopher’s stone (“the alchemists’ researches aimed at the production of gold,” notes Zamani, are “primarily a metaphor for physical purification” and offer “a symbolic parallel to the Surrealists’ desire to plumb the innermost depths of the human imagination”), to later cite Paracelsus, the Kabbalah, Albertus Magnus, �?liphas Lévi, Cornelius Agrippa and many others. It should be noted that, in the 1930s, Breton often frequented the Swiss artist Kurt Seligmann (Basel, 1900 - Middletown, 1962), to whom, moreover, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection exhibition devoted an entire section: A collector of hermetic texts who joined the Surrealist movement in 1934, Seligmann played an important role “in fostering the link between the Surrealist group’s activities and loccult, especially during the period of exile in the 1940s, when magic and myth became two of the movement’s most pressing interests,” writes Subelytė.

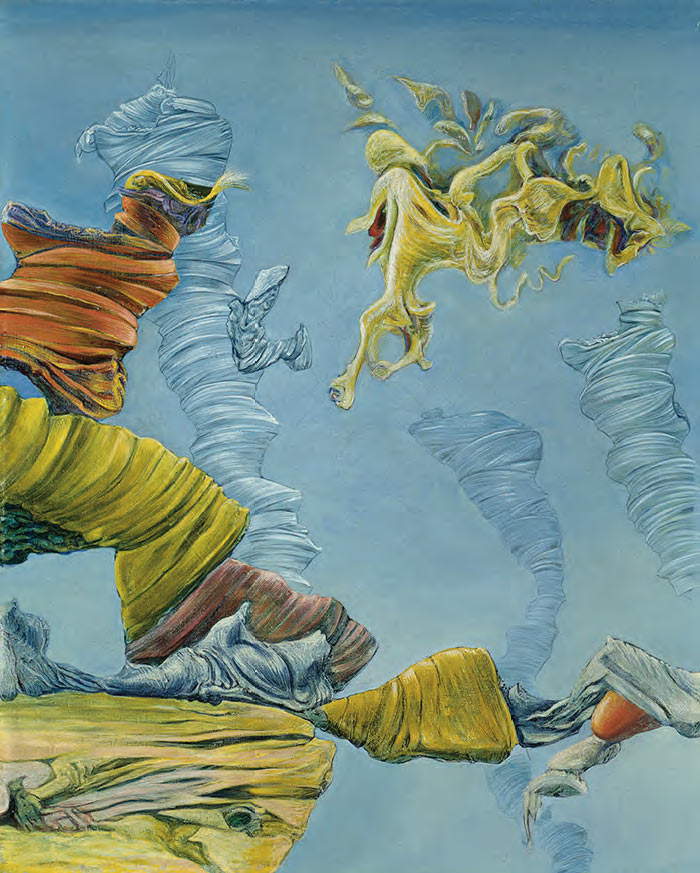

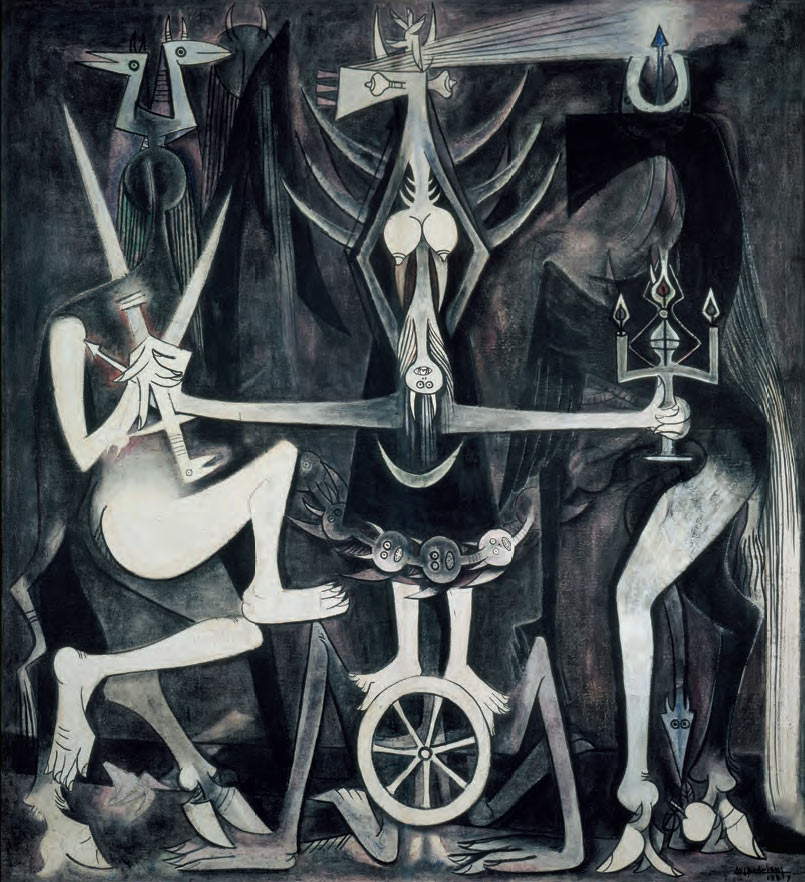

Seligmann’s ideas are fundamental to understanding how Surrealism looked at magic, especially in the years before and after World War II: for the Swiss artist, magic was a force capable of emancipating human beings as an alternative to reason, which had failed to prevent the tragic upheavals of world conflicts. Thus, several of his paintings drew on occult literature and esoteric themes: examples include works such as The Sorceress of 1950, or again Melusina and the Great Transparencies of 1943 or The Devil and the Madman of 1940-1943. While the reference to tarot is particularly evident in the latter work (it can be seen as an allegory of the clash between the grim reality of those years, symbolized by the devil, and the unconsciousness, irrationality and spirit of adventure embodied instead by the madman: “in order to gain wisdom and experience, the madman, and by extension man, must take his own spiritual journey through life,” explains Subelytė who adds that in Seligmann’s works “the seemingly fantastic iconography implies a profound moral and political message.”), Melusina and the Great Transparencies instead draws on the myth of the fairy Melusina, particularly dear to the Surrealists (the protagonist of Breton’s Nadja felt a strong closeness to Melusina), and here alludes to the importance of the feminine power of regeneration. The “great transparencies,” on the other hand, are supernatural beings imagined by the Surrealists themselves (the first to speak of them was Breton in 1942), invisible, capable of influencing the thoughts and lives of humans.

Also central to the art of many of the Surrealists isalchemy, the complex of practices of medieval origins that aimed to transform matter (Brauner, in 1940, even dedicated one of his paintings to the philosopher’s stone, the object that the Archimists claimed was capable of turning vile metals into gold). References appear as far back as the Second Manifesto of Surrealism, where Breton wrote that “Surrealist researches present, as to their objective, a remarkable analogy with alchemical researches”: alchemy, for the Surrealists, is also a symbol of regeneration indicating, writes Will Atkin, “psychic, not material, change and transcendence.” Surrealists “are fascinated not only by the correlation of alchemy with metamorphosis and renewal, but also by the erotic and gendered implications, particularly the metaphorical description of the elemental fusion that originates the philosopher’s stone as the sexual/androgynous union of man and woman, king and queen, sun and moon. The multifaceted alchemical union found in many Hermetic literary texts and their accompanying illustrations makes these metaphors all the more attractive to the surrealists’ collective imagination.” Among the Surrealists most fascinated by alchemical imagery is Max Ernst (Brühl, 1891 - Paris, 1976), who makes this proclivity manifest with The Dressing of the Bride, a metaphor for the “preparation of reagents for chemical nuptials,” Atkin explains: “the marriage of the groom and the bride is suggested through the union of the king’s red robe and the naked female body of the white queen.” Alchemical nuptials, or chemical nuptials, are symbolic of union and transformation, as the union of the alchemical King and Queen, who represent opposites and become the protagonists of several surrealist works( Max Ernst’sThe King Plays with the Queen, Victor Brauner’s The Lovers, Wilfredo Lam’s The Wedding ) is an allegory of metamorphosis, transformation.

It speaks of fusion, in this case between human beings and plants, in a painting by André Masson (Balagny-sur-Thérain, 1896 - Paris, 1987) entitled Goethe and the Metamorphosis of Plants, an allusion to the theme theorized by Goethe in his 1790 essay entitled, precisely, Metamorphosis of Plants, which hypothesized different evolutionary stages of plants, all born from a single original plant, the Urpflanze. In Masson’s painting it is Goethe himself who is transformed into a plant: the theorist thus comes to a complete overlap with the object of his study. Not even Salvador Dalí (Figueres, 1904 - 1989) remained insensitive to the fascination with alchemical themes: evidence of this can be seen in an early work such as Morning Ossification of the Cypress, circa 1934, a work that postulates the transformation of the cypress tree into stone, while the horse coming out of the cypress tree could take on a further allusive character (the horse as a symbol of strength breaking free from the fetters of matter). More difficult to understand, however, is the meaning of the pipes that appear near the horse.

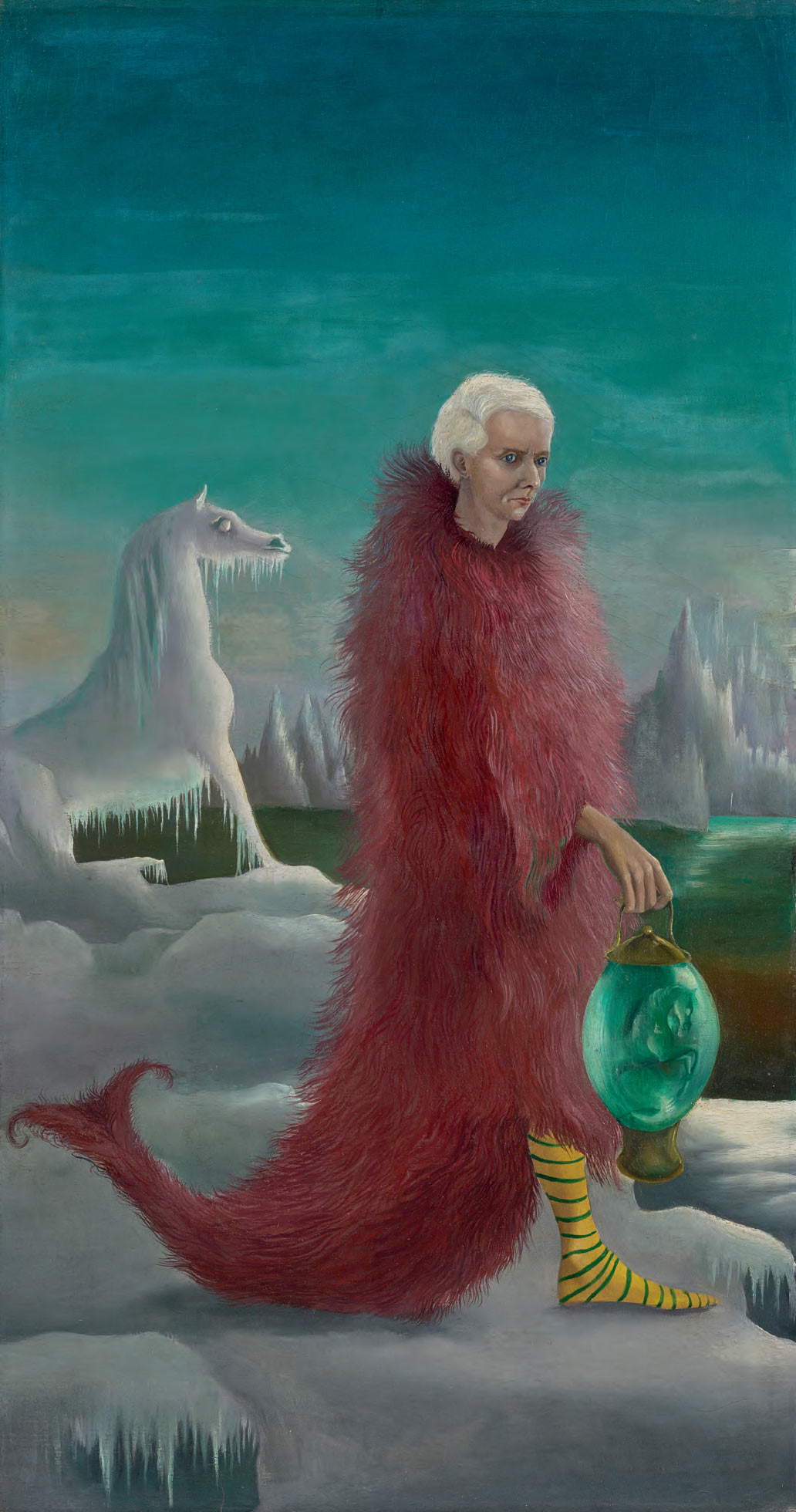

Another figure strongly fascinated by alchemy was Leonora Carrington (Clayton Green, 1917 - Mexico City, 2011), author of a Portrait of Max Ernst in which the companion is depicted, writes Victoria Ferentinou, “in the guise of a hermit/alchemist covered in feathers and holding an egg-shaped lantern, in which is kept a miniature white horse, a symbol of the Celtic goddess Epona, whom Carrington often uses as a kind of artistic alter ego. In many other works the egg is at the center of magical rituals of transformation overseen by supreme female entities or in the alchemical/pagan processes of the sacred nuptials between the male and female principle, set in interiors imbued with a sacred atmosphere.” Even more explicit become the references in The Necromancer, a work in which everything is aimed at symbolizing the union of opposites (the figure of the artist-magician himself is dressed in black and white), in a setting that closely resembles an alchemist’s workshop.

Breton’s passion for magic would continue for a long time: indeed, the culmination would come in 1957 with the publication of the book L’art magique, which remains perhaps the one in which the relationship between art and magic is developed in the most thorough manner. The idea, more than thirty years after the formulation of the first Surrealist manifesto, had not changed: magic, esotericism, and occultism make imagination a fertile ground for artists’ creativity, removing it from the domain of reason. For Breton, magic is fundamental: it is an expression of a strong will, it rejects resignation and submission, it implies “protest, if not revolt, as well as pride.” And precisely because of this important value, the relationship between magic and surrealism has been the subject of in-depth research by several scholars, beginning with Michel Carrouges, who addressed the topic, even while the surrealists were still in full swing, with his 1950 study André Breton et les données fondamentales du surréalisme, and then culminating in 2014-2015 with the exhibition Surrealism and Magic, the first on the subject, held at Cornell University’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum and later at the Boca Raton Museum of Art.

In conclusion, it is interesting to point out the special prominence in Breton’s L’art magique of the image of Leonora Carrington’sSelf-Portrait now housed at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The English artist had contributed to Breton’s book by responding to a questionnaire on the value of magic in the world, sent to about seventy other people, including artists, poets, art historians, ethnologists, and anthropologists (the story, in the Surrealism and Magic exhibition catalog, is reconstructed by Susan Aberth): Leonora Carrington responded by stating that her intent was to spur contemporary man to “rush to the primordial confusion where the golden lion gazes with his round eyes, in the depths of the lotus, milk-rumped lunicorn, bathed in the restorative tears of the new moon,” with the goal of arriving at a “Return to the source of things,” because “only in the bizarre ocean of magic can lexere find salvation for himself and his sick planet.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.