Gombrich said that when we look at a painting (or a work of art in general), we often don’t think about the enormous efforts, sacrifices, and sleepless nights that an artist has spent studying a detail, choosing the right shade of color for a detail, working out a satisfying pose, and rendering a character’s expression to the best of their ability. What we see is the finished painting, that is, a result, which is, however, the result of a long and laborious process: and this is as true of the larger, magniloquent and richly detailed paintings as it is of the contemporary works of art that seem so simple and straightforward instead. And when we are confronted with the finished result, Gombrich used to say, we sometimes fail to realize that the details of a painting that we most admire, those that best arouse our emotional response to the work or stimulate discussions around the masterpiece we are looking at, are not the ones that represented the most difficult problems for the artist.

Let us take a painting familiar to anyone who has been to the Uffizi at least once in their life: the Madonna of the Goldfinch by Raphael (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520). It is such a beautiful, harmonious, refined, and delicate painting that not only does it seem to us to be the result of natural talent, but as a result of this, it seems almost immediate, in the sense that it seems that the artist was able to produce a masterpiece like this with ease, without thinking too much about it. The observer usually dwells on the expression of the Madonna who communicates a deep maternal love, or on the gazes of St. John and the Child Jesus, caught in their sweet tenderness, or even on the thoughtful gesture of the Virgin who, with her right hand, seems at the same time to caress and protect St. John offering the goldfinch to the Child Jesus who, in turn, affectionately attempts to caress the bird.

|

| Raphael, Madonna of the Goldfinch (1506; oil on panel, 107 x 77 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

Yet the attitudes and expressions of the characters were not the main concern for the great Urbino. We understand this from the preparatory drawings for the Madonna of the Goldfinch that have survived the centuries and are preserved in theAshmolean Museum in Oxford. These drawings make us aware that for Raphael the expressions of the characters were not what distressed him: they were details that the artist practically took for granted. His main problem was composition. In fact, Raphael aimed to find the correct balance, the arrangement that would give the best possible harmony to the finished painting, the right proportions, the right distances between one character and another, the poses that would best suit a well-balanced end result. By looking at the drawings we are thus able to see the evolution of the composition toward its finished forms.

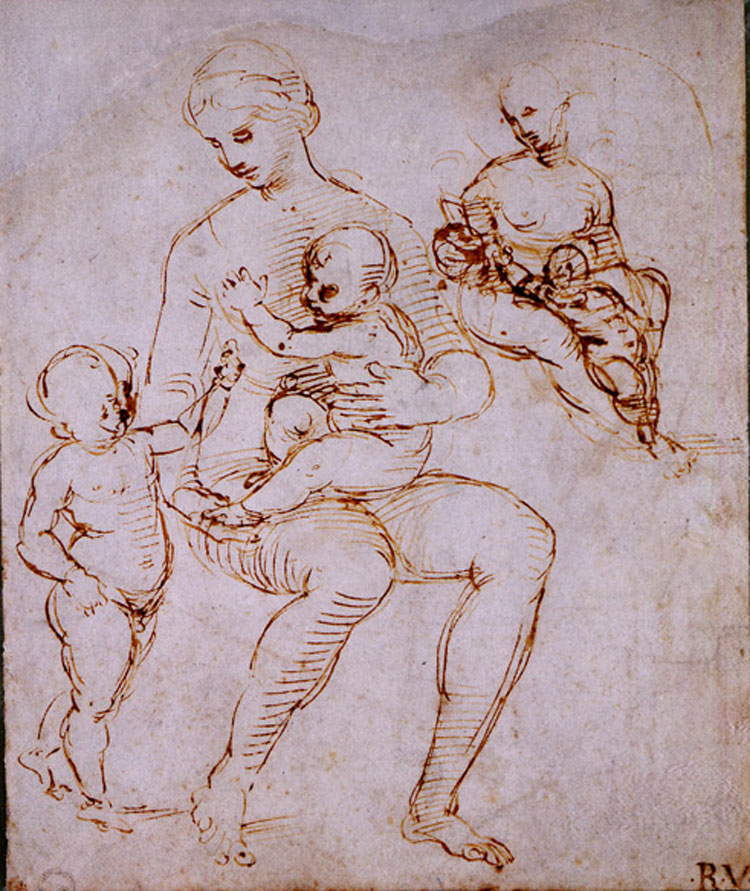

In the first drawing, inventory number WA1846.159 (1846 is the year it became part of the Ashmolean Museum’s collection), the Madonna holds the Child in her arms, who seems almost to cling to her breast, while St. John is standing on the left, drawing his hand closer to the baby Jesus, under the Virgin’s gaze, which is already turned toward him, as in the finished painting (only the head is more inclined downward). There is an interesting detail: Raphael drew the Madonna with bare legs. This is simply an expedient to study the position of the legs under the clothing in order to paint the robe as naturally as possible. A mark at shoulder height, on the other hand, tells us that the artist already had in mind that the robe should have a wide neckline: the same one we observe in the Uffizi painting. We realize, however, that this composition was probably not satisfactory to the artist from a sketch drawn on the same sheet. The dimensions are smaller and the stroke is more sketchy, but even this sketch, drawn with some rapidity, is very useful to help us understand how Raphael had, after a very short time, changed his mind about the arrangement of the characters. The Child Jesus thus begins to assume the pose that he will have in the painting: standing, between the Virgin’s legs, in a pose that with all evidence traces that of Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges, a highly celebrated sculpture finished before August 1506, thus finished at about the same time that Raphael was waiting on his own Madonna of the Goldfinch.

|

| Raphael, Two Studies for the Madonna of the Goldfinch (1506; ink drawing on paper, 24.8 x 20.4 cm; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Inv. WA1846.159) |

It is worthwhile at this point to digress briefly into the dating of the painting and the occasion for which it was made. The commission came from a wealthy Florentine merchant, Lorenzo Nasi, who, according to research carried out on the occasion of an exhibition on Raphael held in Florence in 1984, married Sandra Canigiani, a member of another wealthy Florentine family, between 1505 and February 23, 1506. According to Vasari’s account, the Madonna of the Goldfinch was painted on the very occasion of the marriage: ’ Ebbe anco Raffaello grandissima amicizia con Lorenzo Nasi, al quale avendo preso donna in quei’ giorni, dipinse un quadro, nel quale fece fra le gambe alla Nostra Donna un Putto, al quale un San Giovannino tutto lieto porge un uccello con molta festa e piacere dell’ uno e dell’altro. The work was therefore executed at the time when Michelangelo was awaiting the final stages of the Bruges Madonna: surely Raphael must have been well aware of it, since both he and Michelangelo were working, in 1506, in Florence. And that there is a certain Michelangelo-ism in the painting (this is one of the first cases in Raphael’s production in which one can observe closeness to the great sculptor’s manner) is also evident from the “gigantism” of the two small protagonists at the feet of the Madonna, as Adolfo Venturi had noted as early as 1916 (note the physical mightiness of the baby Jesus). Venturi had also identified Leonardo da Vinci ’s earlier Virgin of the Rocks as the original “model” of the pyramidal structure that Raphael decided to give to the characters: a model filtered, however, again through the Madonna of Bruges, through which Michelangelo organized the Leonardesque “pyramid” into a solid tower-like construction, probably to recall the famous epithet “turris eburnea” that one reads in the Song of Songs but was later attributed to the Virgin.

|

| Left: Michelangelo, Madonna of Bruges (1505-1506; marble, 128 cm high; Bruges, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk - Church of Our Lady). Right: Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the Rocks (1483-1486; oil on panel, 199 x 122 cm; Paris, Louvre). |

In the second Oxford drawing (inventory WA1846.160) we see how Raphael comes even closer to the finished painting. The Madonna’s head begins to turn away from the three-quarter position she had in the previous two sketches, and the posture of the Infant Jesus is already the final one: standing between his mother’s legs, looking toward St. John, his left arm stretched across his body and his right arm stretched up to caress the goldfinch, his legs in slight contraposition. Beyond the pose of St. John, which here Raphael imagines already in profile, but in a more static position than the St. John of the finished work, what strikes us most is theobject that attracts the Child’s attention: in this drawing, in fact, it is not the goldfinch that is at the center of the play of gazes between the characters, but rather a small book that, in the Uffizi panel, will move to the Virgin’s left hand, away from the care of the two children.

|

| Raphael, Study for the Madonna of the Goldfinch (1506; ink drawing on paper, 23 x 16.3 cm; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Inv. WA1846.160) |

The inclusion of the goldfinch was thought, in all likelihood, to present a direct reminder of the Passion: in fact, the goldfinch was believed to live among thistle plants (thus the allusion to the crown of thorns is immediate), hence the name of the little bird, and in addition the red spot on its snout was also considered a symbol of the blood shed by Jesus on the Cross. The painting, moreover, cracked in 1548, when a landslide caused the Nasi family home in which it was housed to collapse, and the work was affected: it fortunately managed to save itself, however, but had to undergo a quick restoration carried out by Giovan Battista Nasi, son of Lorenzo, the commissioner (Vasari himself gives us this information). The problem is that the continuous maintenance work the work underwent over the centuries ended up causing the Madonna of the Goldfinch to become covered with an amber patina, which was removed only with a recent restoration (completed in 2008 and carried out by Patrizia Riitano and Ciro Castelli of theOpificio delle Pietre Dure, under the direction of Marco Ciatti and Cecilia Frosinini), conducted with the aim of bringing back to light, through a cleaning operation and integration of the gaps, the painting’s original colors.

|

| The Madonna of the Goldfinch before and during restoration |

The result is what is now before the eyes of all visitors to the room dedicated to Raphael’s paintings in the Uffizi Gallery: in fact, the restorers have allowed us to appreciate the work with the eyes of a sixteenth-century observer, giving us the opportunity to see even details that the stratifications that have accumulated over the years (these are additions inserted during the maintenance operations that the work has undergone over the centuries) had hidden. We can thus rediscover, in all their brilliance, the chromaticisms of those two children so appreciated by Vasari for being “so well colored and with such diligence conducted that they more readily appear to be of living flesh than worked with colors,” of the Madonna who “has an air truly full of grace and divinity,” and of all those details that in the description of the great art historian from Arezzo are summed up in a single adjective, of disarming banality, but very communicative: “beautiful.”

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.