To see Enzo Tinarelli’s mosaics it is necessary to see his painting; to see his painting it is necessary to get lost in the midst of his mosaics; to grasp the soul of his art, it may be useful to review a contribution that, it was the early 2000s, Valerio Rivosecchi, now holder of the chair of the History of Contemporary Art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, had written on the painting that Tinarelli had produced in those years: “a painting that presents itself to the eyes of the viewer ’with an attractive and decorative guise, made up of elegant spatial balances, sumptuous chromatic accords, volutes and musical dissonances.’” At first glance, even certain of Tinarelli’s mosaics, especially the mosaics produced in that period (but the same reasoning can be extended to his early works), might appear as a kind of chromatic whirlwind, a Schonbergian score, an explosion of lines, planes, fragments, colors, shades, translations of an idea of free randomness that Tinarelli has always affirmed from the very beginnings of his research: art, he tells me, for him is essentially sabotage, the affirmation of a principle of freedom. An assumption that has remained stable throughout his career, which began at the end of the 1970s (the recent exhibition curated by Giovanna Riu in Carrara, in the rooms of Palazzo Binelli, entitled Assolo per mosaico. Works 1979-2024, has entirely retraced it), able to range continuously between painting, mosaic and drawing considered three autonomous moments of a single research. A research that is essentially gestural (and has remained so over the years), a research that finds its roots in a precise cultural temperament, in those decades in which Italian art, after having sought the extreme peaks of experimentation on sign and matter, was trying to continue to make a synthesis with tradition. Tinarelli’s art sprouted from the informal art that, in the years preceding his training, had spread in the Po Valley area: his references and ideal masters were, to name but a couple, Mattia Moreni and Germano Sartelli, artists who shared an interest in matter, considered itself a means of expression charged with physical, visceral and gestural tension, and then matched by a radical attitude and a strong creative autonomy. His material master had instead been that Sergio Cicognani who had worked with Severini, with Mathieu, with Kokoschka, an artist by trade, a “mosaic painter” as he was often called, who could not fail to initiate his pupil into the secrets of mosaic (and for Cicognani, it is useful to remember, a good mosaicist must also be a good painter). One senses, however, in Tinarelli’s art, from the very beginning, the precise desire to unite the most modern experimentation with an older background that he himself, a native of Ravenna, found in Byzantine mosaic. And it is not merely a matter of technique: never, at any point in his career, has mosaic posed itself as a translation of painting (as it did for so many other artists). Tinarelli vigorously claims the autonomy of mosaic, Tinarelli reaffirms in a stentorian voice the recognizability of mosaic, Tinarelli affirms the strength of mosaic, which for him is not only a matter of color, but is also heaviness of work, heaviness of matter (although he has often proven to be able to ’lighten it almost to the point of paradox), heaviness of a direct technique that reflects the idea that mosaic had in the Ravenna of the ancient centuries, where mosaics had, yes, a function that was often practical, everyday (they were bases for altars, for tables, for floors), but they also had a contemplative function that was exalted in the third dimension. Light dominates mosaic and transforms it because mosaic is made of signs, of matter, of invention, of discontinuities, of timbres. Mosaic is light that becomes solid.

That at the basis of Tinarelli’s work there was this idea, however, has been clear for some time: Enrico Crispolti, who has written several texts for Tinarelli, could declare without mincing words as early as 1989 that the Romagna artist “practices mosaic as a total medium, not as a place for the transfer of images elsewhere elaborated, but as a particular material occasion. Which therefore allows a constitution of icono-formal evidences closely related to a diversity of material adjectification, by thicknesses of the tesserae, or how much by their chromatic variety.” And then he added, already at those heights, that Tinarelli “is one of the rare operators in mosaic, even in mosaic indeed, in current ways, that is to say, retrying linguistic possibilities connected with a certainly particular material phenomenology and a technique at once ancient and called into question by new communicative instances.” And such he has remained to this day: a rare artist, although it is not uncommon to hear today about “mosaic,” in the widest meanings of the term (what we see on computers is mosaic, the pixel is the tile, “mosaic” has become an easy synonym to indicate sometimes a more or less shapeless mixture, sometimes a strategy, but we are always talking about pretexts, about accidents). An artist who has well in mind what, for him, the mosaic is: a fragment provided with an idea of unity. And therefore Enzo Tinarelli is among the rare artists today who are able, and perhaps not only in Italy, to express poetry, to express autonomous art with the medium of mosaic.

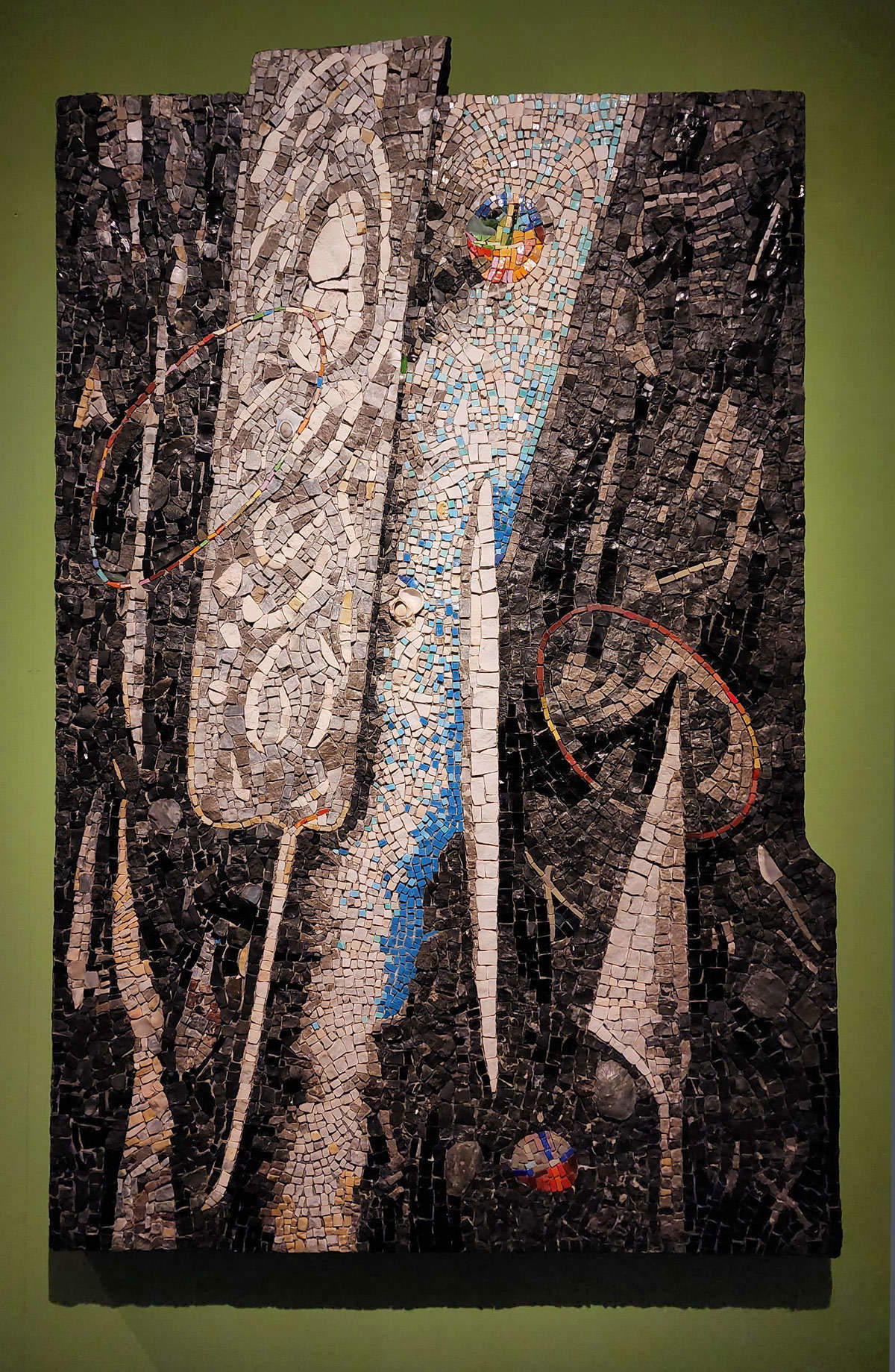

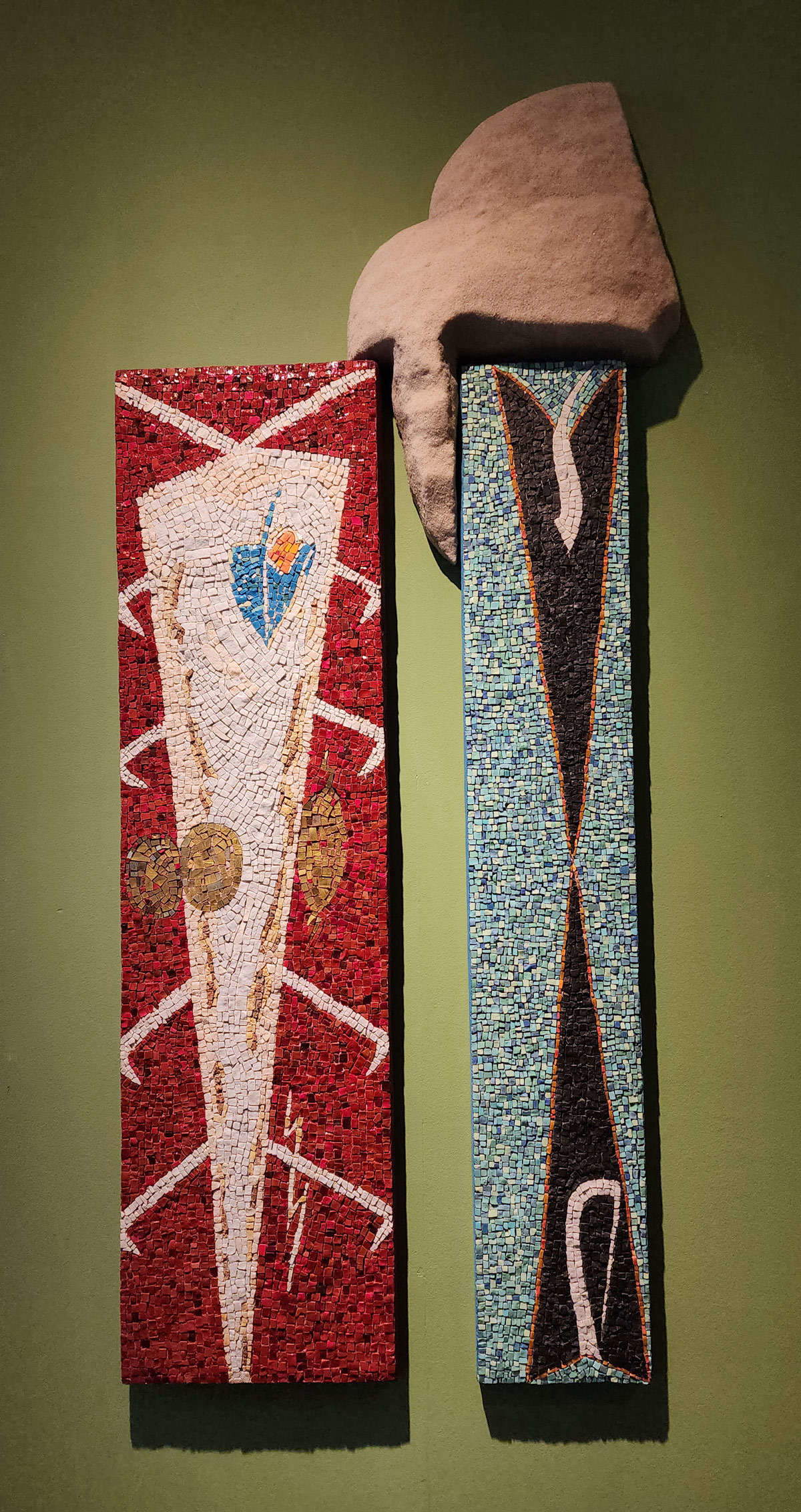

From the earliest works untied from a more experimental phase (a phase evident in the works of the late 1970s and 1980s, Compositions in which the 18-year-old artist, while attempting to engage in an early confrontation with the medium, already reveals a full mastery of the material) an energetic gesturality, full of vitalism, that seems almost instinctive, is evident: works such as Scorre a fiotti il terrore menaccioso (1984) and Matrice anamorfica (1985) demonstrate more than others Tinarelli’s desire to investigate all the potentialities of a mosaic that not only seems almost to explode in chromatic vortices, but even ends up digging the surface, creating lumps, depressions, rises, descents, protrusions. Mosaic, it is known, is surface work. In mosaic there is no perspective (indeed: mosaic denies perspective). It is “skin,” Tinarelli would say: but it is a skin that he tries to make flesh. And so the artist seeks depth in every way. By working on the irregularity of the surface, or, as Tinarelli has done from the beginning, by experimenting with more or less anamorphic techniques in his works, by working on lateral gazes. In the works of the 1980s, there is an irrepressible, fiery, intense sign, which clicks, which darts, which is endowed with an incandescent expressive force; it is life that becomes a gesture and flows on the surface of the mosaic.

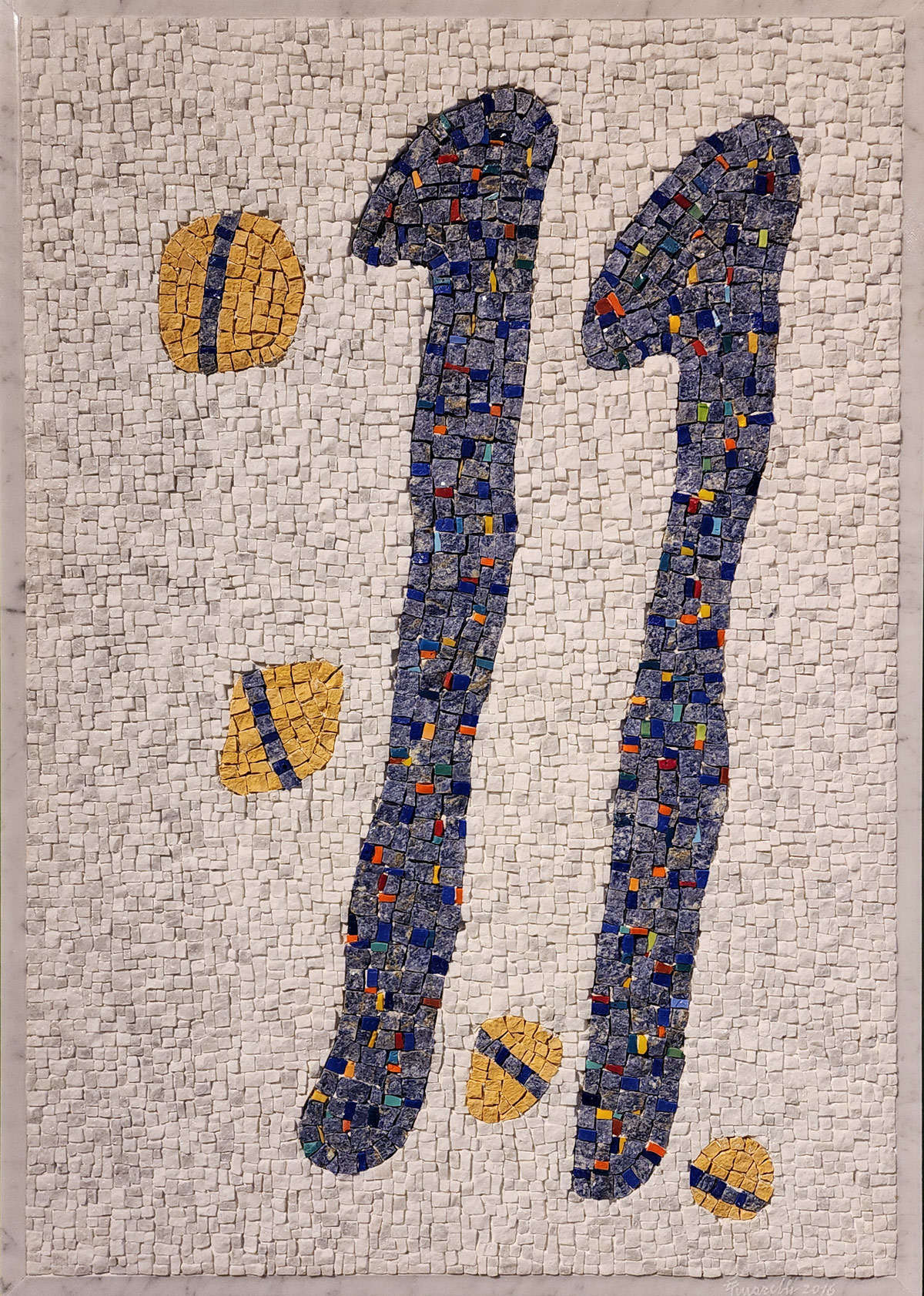

Life, one would say, in the true sense of the word, since one of his strands of research, especially between the late 1980s and the 1990s, has long investigated the very principle of existence: cells, DNA strands, chromosomes that inevitably find their double in the tessera, itself cell, primordium, source, unitary element. An inquiry that seeks to probe the structures, the connections, the networks that govern our very existence as living organisms. The origins of this idea, Rivosecchi noted again, are to be found again in Byzantine art: as the mystical cross of St. Apollinare in Classe is not a depiction, it is not an indication, but is if anything a direct vision of the idea of Christ, it is a vision of divine light manifested in a blue sky, similarly Tinarelli’s chromosomes and DNA strands are not a representation of our biological life but are a vision of science “through its magical tools,” writes Rivosecchi, “and now surely more influential in our imagination than all the symbols of ancient religions.”

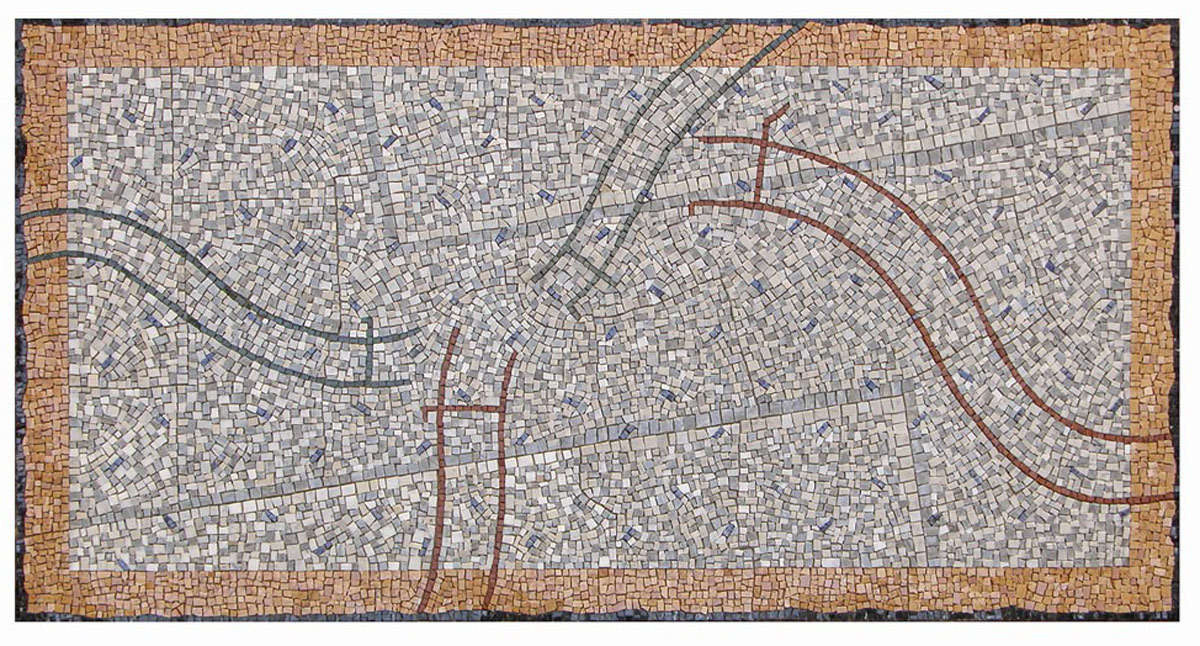

Natural then that this exploration of the biological origins of our existence expanded beyond the scientific references that had characterized the production of the 1990s: so if at that time the works anchored themselves to cellular sequences and, in general, to all the symbols of the invisible organization of human life itself, since the 2000s Enzo Tinarelli’s poetry has transformed that language into a broader visual texture, where the structural element becomes evocation, path, memory in motion. The mosaic, it has been said, for Tinarelli is always a fragment, albeit endowed with its own unity: in recent years this consistency has become more evident, each of his mosaics seems a piece of infinity crossed by the paths of our existence. It is not uncommon to come across, in the most recent mosaics, what he calls “genetic tracks,” the prodromes of which are to be found in his previous production: they are lines, filaments, parallel fragments that cross the surface of the work, like inner traces of our lives. Therefore, they are neither rigid nor geometric, but neither are they instinctive and disordered: they flow freely as if drawing emotional scores, they are emphases that make manifest a kind of tension between order and disorder, between planning and instinct, as if the mosaic became an attempt to translate a life experience into an essential language. To be concrete, one of the highest and most poignant proofs of this strand is Se trouver dans la foule (2003), a carpet of polychrome marbles in which the tracks allude to the lives of the artist and his three children, converging, coming together and then moving apart, because, Tinarelli tells me, that is how life itself works.

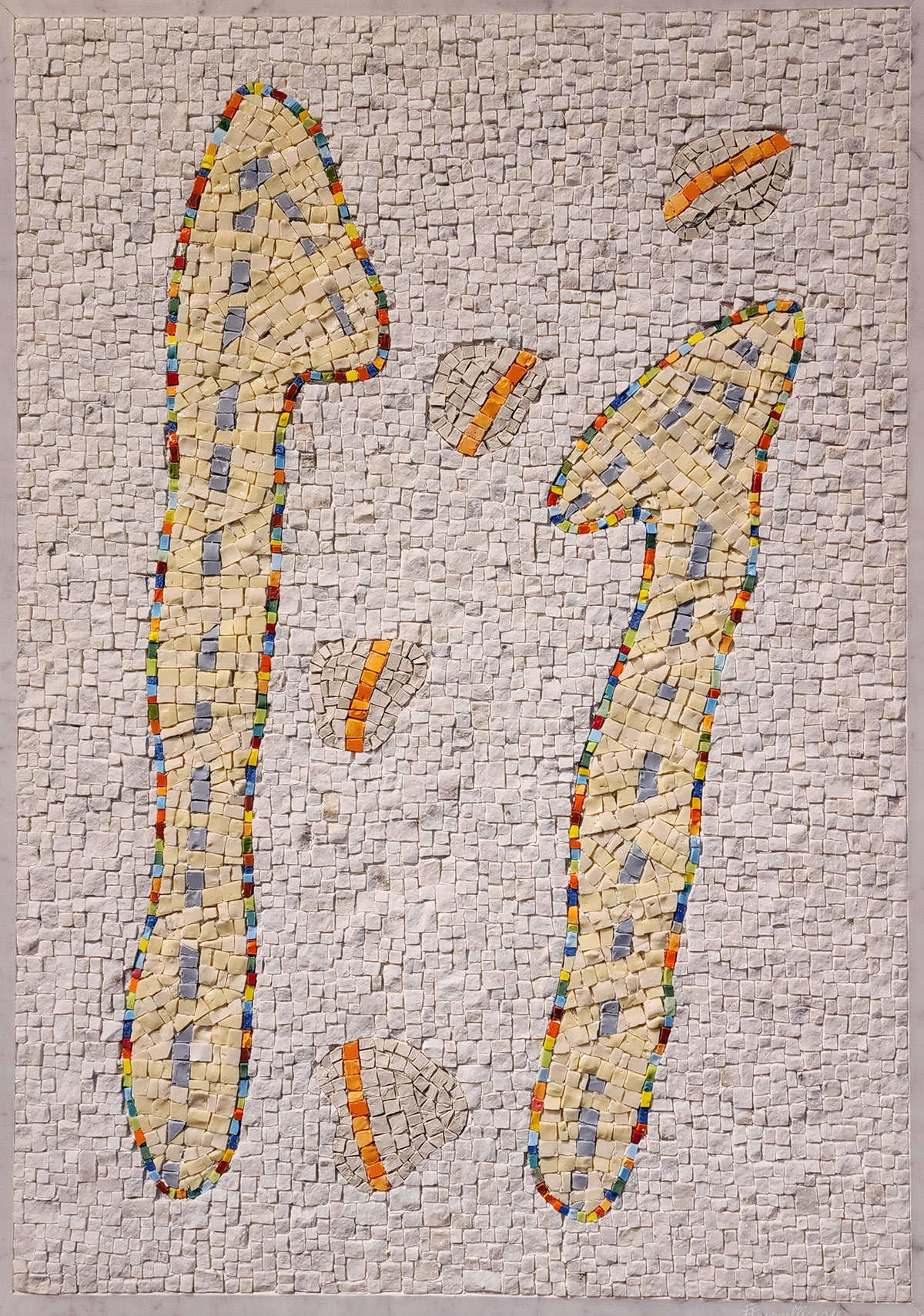

The motif of the runway (and, consequently, the never dormant interest in biology and genetics) also returns in the latest works(Isole, Slittamenti, Sospensioni, which belong to the production of the most recent years), often even in the title(Piste funambule). The force of color that pervaded his earlier works has here abated a little, often the lines of his compositions cross pages of white marble, but Tinarelli remains a pure colorist, in the classical sense of the term, an artist who works, Baudelaire would have said, defining forms through the “harmonious contrast of colored masses,” expressing his epic poetry with the vigor and at the same time with the delicacy of his elegant chromatic textures. These recent works, produced in the last ten years, start from abstract ideas on which elements referable to something concrete are grafted (arrows, flames, doors, passages, crossings, rivers, bridges, hooks... ) with the idea of starting from a datum, suggested with the title, to transport the relative elsewhere. Existence, after all, does not proceed by straight trajectories, but unfolds as a path made of detours, returns and unexpected revelations: these trajectories are the subject of the Ravenna artist’s most recent works. A subtle temporal oscillation can then be felt in his work, a desire to go beyond the linearity of chronology to access a deeper vision of time, as if to say that time is a fabric rather than a sequence. Moreover, it is the very medium of the mosaic that activates this possibility. An art of composing and recomposing, a free, joyful, serious, solid and at the same time often ironic poetic act.

Moreover, there is also no lack of a more playful component in Tinarelli’s production, which the artist considers a form of divertissement. The example of the series Sui modi di dire cuore (On the Ways of Saying Heart), begun in 2010, a survey of the shape of the heart as an emotional archetype that becomes a light-hearted reflection, and at the same time innervated with trepidation, on our daily affectivity everyday (the mosaics, which ironically reproduce idioms and proverbs having to do with the heart, are all accompanied by poetic texts written by friends, artists, and critics whose paths have crossed with Tinarelli’s). Or the series of flooded books from 2003, a small nucleus of works that arose out of a tragic event, namely the flood that hit Carrara that year and inundated the artist’s studio, causing him to lose many, precious books (and precious in every sense of the word: for their content and for their cost), including his beloved catalogs on Ravenna mosaics or volumes on the history of mosaics: Tinarelli gave new life to those books through mosaic, transforming them into elements of works of art capable of recounting that loss without a sense of regret, with the idea that even an object that has ceased the function for which it was intended can take on new, meaningful meanings.

Tinarelli’s works are, in essence, hymns to life. They were so in the 1980s, they have been so throughout the itinerary of his artistic journey, they still are, even when they take on a more playful and playful facies . And the most recent works have translated the artist’s imagination into poetic forms that refer to a human condition as a path made up of fragments of experiences that are layered, separated and recomposed continuously over time. They are not representations of life: they are, rather, visions. Visions of an artist deeply in love with mosaic, deeply committed to mosaic. Visions in which, moreover, matter and idea live in total symbiosis: references to the practice of mosaic abound even in the titles, there is even a case of an onomatopoeic title that refers to the mosaicist’s craft(Rito rode pick tack of 1988). Visions in which it is also not uncommon to see the ancient and the contemporary in dialogue, sometimes even in a direct way, as when, in 2017, his Tovaglia romagnola was placed in the crypt of the basilica of San Francesco in Ravenna for that year’s edition of the Biennale del Mosaico. Poetic visions, in essence. It almost seems as if, by means of fragmentation and harmony, of a gestural and controlled abstraction, of a sign that brings the surface to life, Enzo Tinarelli wants to suggest that all existence is built in the encounter between chaos and order, between logic and irrationality, between past and present.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.