The most important exponent of neoclassicism was Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 - Venice, 1822), who can also be considered the greatest sculptor of his time. He was a rather unique neoclassical artist: unlike many French neoclassicists, such as Jacques-Louis David, Canova was not politically engaged but, on the contrary, believed that art should remain independent of external pressures. Nonetheless, Antonio Canova did not shy away from producing numerous portraits and commissions for his powerful patrons, towards whom he was nonetheless unprejudiced even if his political views were diametrically opposed to those of his client. Canova is one of the most original interpreters of the neoclassicism theorized by Johann Joachim Winckelmann: in the Venetian sculptor, the German theorist’s ideal of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” is conveyed in works that are far removed from the icy coldness of the Nordic neoclassicists, such as Bertel Thorvaldsen, and are instead animated by an inner feeling and energy that are controlled with intellect and rationality.

Canova is also known for merits that go beyond “produced” art: after the fall of Napoleon in 1815 he was in fact commissioned by the Papal States to bring back to Rome and the territories under papal rule the works that had been looted during the French occupation. It was a very delicate diplomatic mission that succeeded, with Canova managing to bring back to Rome most of the works that had made their way to France.

A moderate artist, of a shy nature, and very religious, Canova was seen by many already in his time as the artist who had resurrected the ancient in sculpture and was considered worthy of being compared to the great sculptors of ancient Greece: the ideal beauty of ancient sculpture had thus returned to manifest itself in the works of the great Venetian artist. His works are still among the most appreciated by the general public because of their balance, smoothness (one of the main characteristics of Canova’s style), and timeless beauty. Canova during his career tried his hand at various themes: mythological subjects (these are probably his most famous sculptures, fromLove and Psyche lying to the Three Graces), religious subjects, and portraits. The artist was also a painter, and there are numerous of his paintings that are preserved today. He can also be considered in some ways the first “contemporary” artist in terms of his working method: in fact, he developed a technique that, through plaster casts, now collected in several museums (the Gipsoteca Canoviana in Possagno, the Musei Civici in Bassano del Grappa and the Gipsoteca of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Carrara stand out in particular), allowed him to replicate his subjects numerous times, to meet the needs and tastes of an increasingly large and important clientele. Canova was ultimately one of the most skilled, original, modern, and innovative artists of his time.

Antonio Canova was born in Possagno, in the territory of the Republic of Venice, on November 1, 1757, to Pietro, defined by sources as a “stone worker and architect” (in fact, he came from a family of stonemasons) and Angela Zardo. Little Antonio lost his father when he was only four years old, in 1761, and was entrusted to the care of his grandfather Pasino Canova, a sculptor, with whom Antonio would also complete his very first apprenticeship. In 1766 he became a pupil of Giuseppe Bernardi Torretti and two years later moved to Venice with his master. In 1773, following Bernardi Ferretti’s death, Antonio became a student of Giovanni Ferrari. In the following months he executed the Canestri di frutta (baskets of fruit ) preserved at the Museo Correr in Venice, which are supposed to be his first independent works. In 1776 he finished work on the two statues of Orpheus and Eurydice that had been commissioned by the Venetian senator Giovanni Falier, while in 1777, when he was only 20 years old, he opened his own workshop, thus becoming an independent artist.

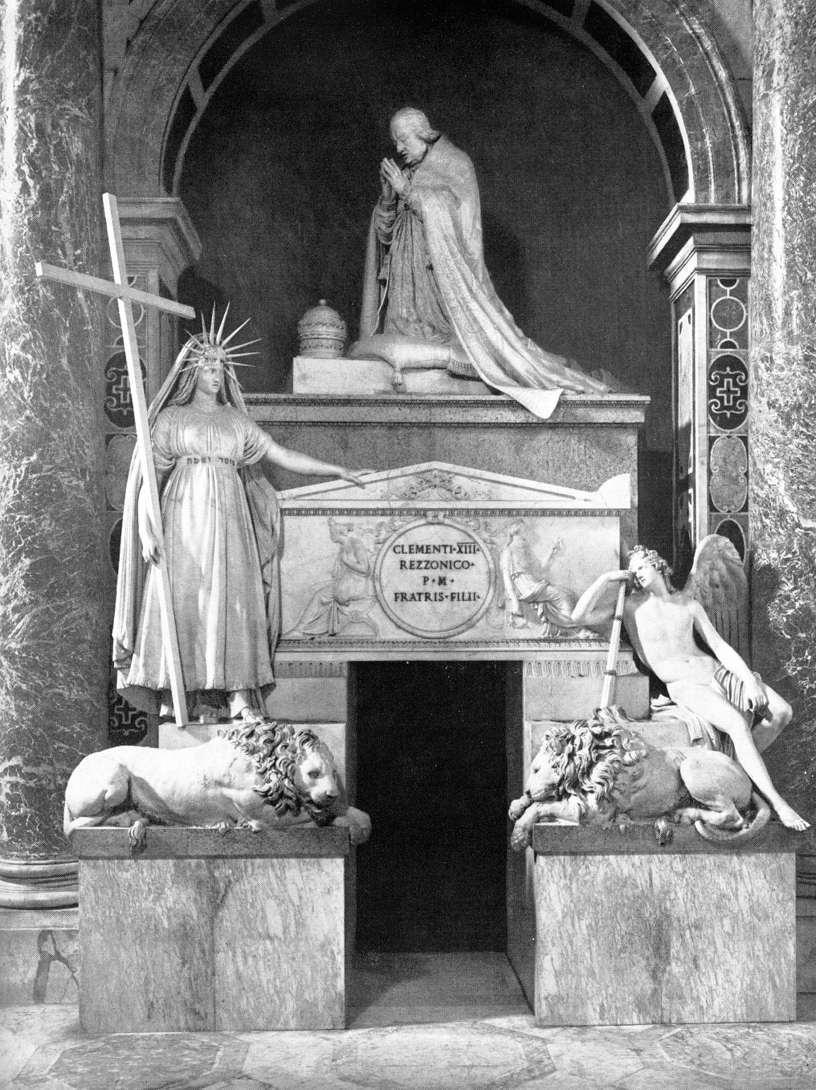

In 1779 he was elected a member of the Venetian Academy and in the same year executed Daedalus and Icarus. In November he began a stay in Rome that would last until June of the following year. The following year, during his stay in Rome, he made a brief visit to Naples, and at the end of the year he returned to Rome again and came into contact with the Venetian ambassador Girolamo Zulian. In 1781 he met Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy and followed the Theseus for Zulian. In 1783, by now an established artist despite his young age, he obtained a commission for the funeral monument of Clement XIV, which was finished in 1787. After finishing it, he returned for some time to Naples, where he met the Englishman John Campbell, who commissioned his most famous masterpiece, Amore e Psiche giacenti: the work now in the Louvre would be finished in 1793. In the same year he began work on the funeral monument of Clement XIII, which would be unveiled in 1792, the year in which the artist traveled between the Veneto and Emilia. In 1794 he executed his famous work Venus and Adonis, and the following year Prince Onorato Gaetani commissioned him to paintHercules and Lyca. In 1798, following Louis Alexandre Berthier ’s occupation of Rome and the establishment of the Jacobin Republic, the French asked him to swear hatred for the previous rulers. Antonio is said to have refused, uttering the phrase in Venetian dialect “mi no odio nissun”: the artist thus left the city and returned to the land of his birth. In Possagno he worked for the parish church and was commissioned by Duke Albert of Saxony to create the mausoleum for Maria Christina of Austria to be destined for the church of the Augustinians in Vienna. The work would be completed in 1805.

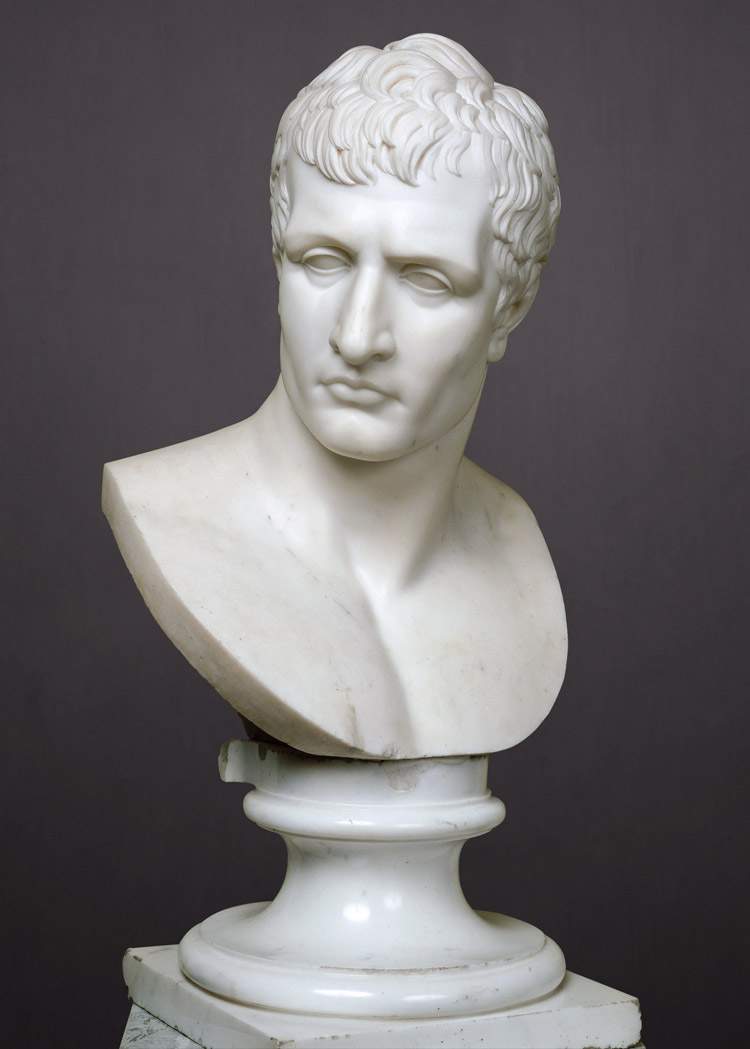

Canova returned to Rome in 1799 and in 1800 became a member of the Accademia di San Luca. In 1801 he made a trip to Paris where he obtained a number of commissions directly from Napoleon Bonaparte: in particular, he was commissioned to make several portraits, including the bust-portrait of Napoleon(read more about the work here). He returned to Rome at the end of the year. In 1802 the new pope Pius VII appointed him Inspector General of Fine Arts for the Papal States, and in 1804 he obtained another appointment from the pontiff, becoming perpetual director of the Accademia del Nudo. In 1805 he made a trip to Vienna for the inauguration of the monument to Maria Christina of Austria, and probably also this year he finished the statue of Pauline Borghese Bonaparte as Venus Vincente. In 1807 he met Leopoldo Cicognara of whom he became a good friend, and in 1809 he moved for some time to Florence where he made the monument to Vittorio Alfieri in the basilica of Santa Croce. In 1810 he is again invited to Paris to become court sculptor, but Antonio declines. However, he travels to France to execute the statue of Empress Marie Louise. In the same year he becomes president of the Academy of St. Luke.

The great sculptor finished work on one of his most famous works, the Italic Venus, in 1811, and the following year he began sculpting the group of the Three Graces , which would be finished in 1816. In 1815, following the fall of Napoleon, the Papal States commissioned him to travel to Paris to reclaim works of art stolen during the years of French occupation. Although with several difficulties, the artist managed to recover many works. In the same year he makes a brief visit to London. In 1816 he returned to Rome and began work on the equestrian monument to Charles III of Spain, which would be finished in 1820 (it can be seen in Piazza del Plebiscito in Naples). In 1818 he was in Possagno where he began work on the Possagno Temple, also known as the Canovian Temple, which would not be inaugurated, however, until 1830, after his death. He returned to Rome the following year and in 1820 stayed one last time in Naples where he was commissioned to paint the equestrian monument to Ferdinand I. However, he failed to finish the work. In 1822, after a stay in Possagno, he began the journey back to Rome but disappeared en route in Venice on October 13. His remains rest in the Temple of Possano, while his heart is in the Funeral Monument to Antonio Canova kept in the Basilica dei Frari in Venice.

After his youthful debut in Venice, a period during which Canova, a great admirer of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, had produced works still tinged with late Baroque taste (such as Daedalus and Icarus, a work from 1778-1779 preserved at the Museo Correr in Venice), his move to Rome marked a decisive change of direction for the artist, and the early work Theseus and the Minotaur can be considered the artist’s first neoclassical work, with Theseus, the Greek hero defeating the monstrous half-man, half-bull being, who is depicted not at the moment of the confrontation, but at the end, as he meditates on his defeated opponent to symbolize the victory of intelligence over brute force. It is an accomplished neoclassical work because Theseus is represented not only as a handsome hero of harmonious and ideal proportions, but also as a man who does not let his impulses get the best of him. The Minotaur himself, moreover, is represented by Canova with a well-balanced body that does not disturb the observer. This is thus the first work from which filters the lesson of classical statuary that had become the artist’s main point of reference. Theseus and the Minotaur guaranteed great success for the young Canova, so much so that it was shortly afterwards that he was commissioned for the funeral monument of Clement XIV, the first of the works in the funerary genre that guaranteed great fortune for the Venetian artist: preserved in the basilica of the Holy Apostles in Rome, the work, though still indebted to Bernini’s statuary (the compositional scheme is in fact that of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s funerary monuments), departs from it in its greater composure and the now total absence of the dynamism of Baroque sculpture. The genre would be further revamped later, for example with the Funeral Monument of Maria Christina of Austria, where Canova reflects on humanity’s journey toward death, symbolized by the figures’ gait toward the tomb, with the original use of a pyramid where the tomb is placed toward which the figures go, arranged according to a strict scansion.

Dating from 1787 (although the work would be finished in 1793) is the conception of Canova’s most famous masterpiece, Cupid and Psyche lying, a reinterpretation of the myth narrated by Apuleius and particularly in vogue in eighteenth-century art: the artist depicts the moment when Cupid, Psyche’s lover, awakens with a kiss the young nymph, who has fallen into a deep sleep as a result of a punishment inflicted on her by Venus (the two figures are depicted at the moment when their lips brush against each other). It is one of the most admired sculptures in art history because of the originality of the composition, the intensity of the moment that is nevertheless soberly controlled, the lighting effects, and the softness with which Canova sculpts the marble(read a detailed discussion of Cupid and Psyche lying down here). However, Canova is not an artist who depicts only languid loves and soft bodies. Indeed, in the Creugante and the Damosseno, statues of two ancient boxers, the artist offers the viewer a glimpse of the strength, power and virility of these two characters, who are depicted by Canova at the climax of their combat, though always controlled.

One of the few works in which the artist transcends his intent to fully control the passions is theHercules and Lica: here, the demigod is about to hurl with brute force the young Lica, who is responsible for having brought him, by order of Deianira (Hercules’ jealous wife), a robe bathed in the blood of the centaur Nessus, which gave the wearer severe pain. Hercules, in revenge, therefore turns on Lica: this is one of the very rare works where feeling prevails over reason, but despite this the composition is carefully balanced, with the bodies of the two characters describing two perfect, opposing arcs. Works such as these drew criticism of Antonio Canova especially from northern European neoclassicists, who disallowed works so far from the ideals of “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur.” Canova then excelled in the portrait genre, rendering idealized images of the subjects who posed for him.

The best known of Canova’s portraits is that of Napoleon Bonaparte, which was produced in numerous replicas, while a case in point is that of Pauline Borghese as Venus Victrix, now in the Borghese Gallery. The commission originated in 1802, when the artist was commissioned to paint a portrait of Napoleon and several idealized portraits of family members, including Pauline Bonaparte, Napoleon’s sister and wife of Camillo Borghese. Pauline is depicted by Canova nude and lying on a chaise-longue: it is a work that refers to the Venetian tradition of reclining Venuses, updated on the repertoire of classical statuary (Canova probably even looked at Etruscan urns), where the beauty of the subject is celebrated through an idealized representation as a goddess of love. The artist achieves here an extraordinary balance between naturalness and ideal beauty, as well as between action and control, producing one of the most moving masterpieces in art history. The same emotion animates the masterpiece of Canova’s maturity, the Three Graces, commissioned by a wealthy English client, John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, who had visited Canova’s Roman studio in 1814 and was impressed. The work, executed from a single block of Carrara marble and anticipated in some ways by Venus italica (the marvelous sculpture made as compensation after the Medici Venus was transferred to France during the Napoleonic spoliations: it is a sculpture in which Canova revisits the classical iconography of the Venus pudica), depicts the dance of the Graces, who are represented by Antonio Canova as three naked women languidly embracing and brushing against each other in an action that was seen by many as charged with overt eroticism (a characteristic that the most intransigent critics would not allow). The elegance of the sculpture, the fineness of the marble workmanship, and the delicate beauty of the three women made this sculpture one of the most appreciated of Canova’s production.

“Canova,” Francesco Hayez had to write in his memoirs, “made his model in clay; then having cast it in plaster, he entrusted the block to his young students so that they could rough him out, and then the work of the grand master began. [...] They would bring the master’s works to such a degree of fineness that they would be said to be finished: but they still had to leave a small coarseness of marble, which was then worked by Canova more or less according to what this illustrious artist believed should be done. The studio consisted of many rooms, all filled with models and statues, and everyone was allowed to enter here. Canova had a secluded room, closed to visitors, into which only those who had obtained special permission would enter. He wore a kind of chamber robe, and wore a paper cap on his head: he always kept his hammer and chisel in his hand, even when he received visitors; he talked while working, and from time to time he would interrupt his work, turning to the people with whom he was conversing.”

Antonio Canova is known for the technique through which he was able to produce numerous replicas of his masterpieces. The first stage was the making of the plaster model, the tool that enabled him to reproduce the works in multiple copies, but even before the plaster there was the drawing (Canova is also known to have been a prolific draughtsman), from which a terracotta sketch was then made, which was then translated into plaster. Small nails, known as "repere," were attached to the plaster casts, which were used by Canova’s collaborators to take measurements and proportions, through the use of a pantograph (these measurements were then reported on the marble). It is for this reason that many Canova plaster casts appear filled with holes: these were the ones in which Canova inserted the repere in order to transfer the measurements onto the marble and reproduce the works in multiple copies. This was work that was carried out by theatelier’s collaborators: Canova, like today’s artists, provided drawings and models and, once the execution phase was finished, finished the work by polishing or finishing it with details.

Canova’s works are preserved in museums around the world. Although it is possible to get an idea of the artist’s entire career by visiting a gipsoteca that contains a significant collection of his plaster casts (such as the one in Possagno, the most important and complete, or those in Bassano del Grappa and Carrara), there are no museums that collect marbles belonging to multiple stages of Antonio Canova’s career. To see his marble works, therefore, it is necessary to travel extensively. The journey can begin in Rome and Vatican City, to see the monuments of the popes and the sculptures in the Vatican Museums (the Creugante, the Damosseno, and the Perseus Triumphant). Rome is also home to Pauline Borghese as Venus Victrix, at the Galleria Borghese, while the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art holds theHercules and Lycaeus. In Florence you can admire the Venus italica (Galleria Palatina in Palazzo Pitti), while in Genoa, at Palazzo Tursi, the marvelous Magdalene is preserved(read an in-depth study of the work here). Also famous is the Hebe, preserved at the San Domenico Museums in Forlì, and reproduced in other examples found in Berlin, the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and Chatsworth House in England. The National Gallery in Parma, on the other hand, welcomes Maria Luigia of Habsburg as Concordia. Three important works are at the Museo Correr in Venice. These are early works: the Basket of Fruit, Orpheus and Eurydice and Daedalus and Icarus.

Abroad, in addition to the Louvre where Cupid and Psyche lie, sculptures by Canova are kept in Berlin (the Dancer with Cymbals in the Bode Museum), Vienna (the Funeral Monument to Maria Christina of Austria in the Church of St. Augustine and Theseus and the Centaur in the Kunsthistorisches Museum), in Geneva (theAdonis and Venus at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire) and in London (the Theseus and the Minotaur at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Napoleon as Peacekeeping Mars at the Wellington Museum). Numerous works can also be found at the Hermitage in St. Petersburg: this is where the first version of the Three Graces is kept, but the Russian museum also holds other important masterpieces (above all theWinged Cupid and the Dancer Hands on Hips).

|

| Antonio Canova, life and works of the great sculptor of Neoclassicism |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.