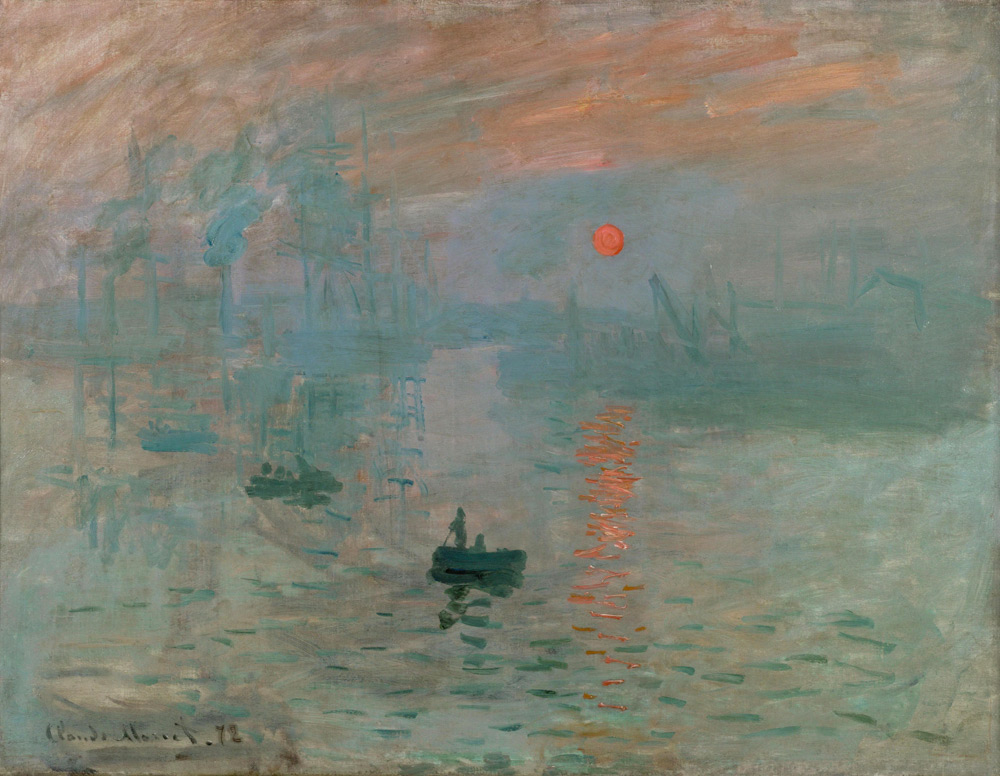

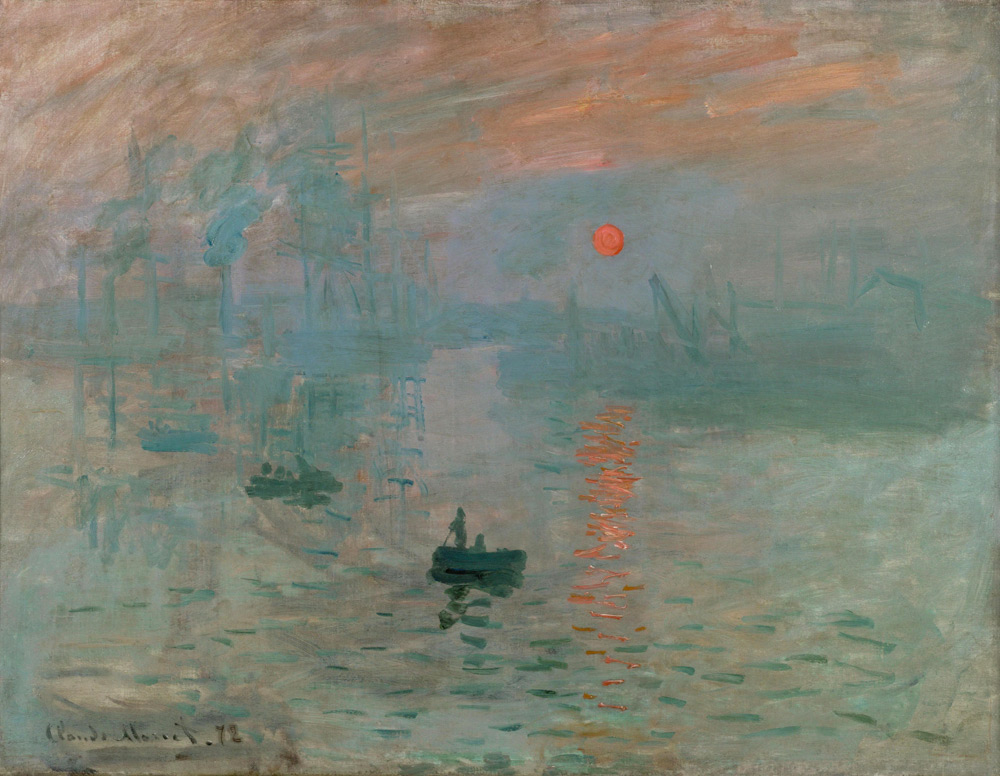

Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 - Giverny, 1926) was one of the major exponents of the Impressionist movement, whose research sees its prodromes dating back to the 1860s. The official date of the group’s activities, however, dates back to 1874, when the Impressionist artists introduced themselves to the art scene with their first exhibition, held at the studio of the Parisian photographer Nadar. Among those who joined, in addition to the aforementioned Monet, were Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The name of the movement, which derives from a work by Monet(Impression: soleil levant from 1872: read a detailed discussion of the painting here), is also linked to the technique used to paint: quick brushstrokes of color, landscapes imprinted on the canvases through direct observation (painting was called en plein air where works, especially landscapes, were painted directly on the place depicted, “in the open air,” in fact), in order to truthfully render the colors that the artist saw. The Impressionists limited themselves to the use of their own sight, but rather conducted studies on the perception of color, precisely because they noticed, for example, that shadows, instead of being dark, reflected the colors of objects. Thus, the group also researches optical perception through the juxtaposition of shadows and light effects. The result the French achieve is the ability to fix a moment, a precise instant in order to reproduce it immediately on canvas. The story goes that some times they would stare for hours at the landscape until they found the “right” moment to capture.

In accomplishing the task of staring at the moment, artists create modern works, almost taken live. The representations, however, are affected by the personality of the artist, who, with his or her wealth of experience, perceives the subjects or landscapes to be portrayed in a unique way. Some critics, such as the German Hans Belting, have considered the movement to be in rupture with the contemporary artistic situation. A different position, however, is taken by Irishman Brian O’Doherty, who identifies the movement as a change related to the desire to go beyond the size of the frame, but which ends when they remain tied to the commission. The frame makes it clear to the viewer that what they have before them is a work. At the same time, however, it delimits its space. In a 1960 Monet retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, conceived by William C. Seitz, paintings were hung without the frame. The result was bewilderment for visitors, who found it hard to believe that those were really Monet’s works, which became, in that circumstance, one with the museum wall.

|

| Claude Monet, Self-Portrait (1886; oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm; Private collection) |

On November 14, 1840, Claude Monet was born in Paris, to Claude-Adolphe Monet and Louise-Justine Aubrée. In 1845 he already moved with his family to Le Havre, Normandy. In 1851 he began to study drawing with Jacques-Francçois Orchard, but it was the fortunate meeting with the painter Eugène Boudin (which took place in 1856-1857) that allowed the artist to approach the art world from another point of view: Monet devoted himself to landscape painting. In 1857 he was orphaned by his mother, and the following year he participated in his first exhibition, a group show in Le Havre. In 1859 he left for Paris, where he formed important friendships with the English painter Sisley and the French artists Renoir and Jean-Frédéric Bazille.

In 1865 he met, on an important commission, the one who would become his first wife, the model Camille Doncieux, who in 1867 gave him his first child, Jean. The young woman’s portrait changed Monet’s career, whose paintings began to be purchased by wealthy and prominent figures. However, the lives of the newlyweds are not easy, as they oscillate between debt and financial straits. In 1870 France entered the war against Prussia, and the Impressionists nevertheless showed little interest in wartime events: this is an important change, because artists in the nineteenth century were, on the contrary, very interested in history and thus in contemporary events. In contrast, the Impressionist generation does not seem to be interested in depicting wars or socio-political events. Monet himself, in those years, painted the beaches of Trouville. It was in 1874 that Monet made his debut at the Impressionists’ exhibition: the first in a series of eight exhibition events. In 1878 his second-born son Michel was born.

In the same turn of years he travels to London, where he sees Turner and Constable, goes to Holland and then returns to France. In search of a home that could give him inspiration for his paintings, as the English did (particularly Turner), he moved away from Paris, the climate having changed and thus the conditions for painting having disappeared. The untimely death of his wife in 1879 caused the artist to fall into depression, and Monet later cut off relations with his friends and fellow painters, although he continued to achieve success (in 1880 he exhibited for the last time at the Salon and managed to have his first solo show organized, in Paris, and even in 1889 he exhibited for the first time in London). After several moves, he decided to take up permanent residence in Giverny, a small village in northern France. Monet moved there in 1892 with his new wife, Alice Hoschedé, also a widow, of a wealthy textile merchant who often bought works by the artist. The house he purchased soon became an artistic paradise, beginning with the artist’s creativity in tending the garden, but also the very tranquility of the home’s location. In his pond he plants the famous water lilies, the object of study at the conclusion of his artistic parabola. While his exhibition activities continue (in the meantime Monet also becomes very popular in the United States, managing to exhibit his works overseas), and while the artist continues to travel (he also travels to Venice), he begins to have problems with his eyesight. In 1911 his wife Alice died, while in 1914 he lost his eldest son Jean, and in 1918, in the last years of his life, his eye problems worsened, so that in 1923 he had to have surgery. In 1926 he contracted lung cancer, which led to the artist’s death on December 5, 1926.

|

| Claude Monet, The Beach at Trouville (1870; oil on canvas, 38 x 46.5 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Claude Monet, Impression: soleil levant (1872; oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm; Paris, Musée Marmottan Monet) |

|

| Claude Monet, The Poppies (1873; oil on canvas, 50 x 65 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

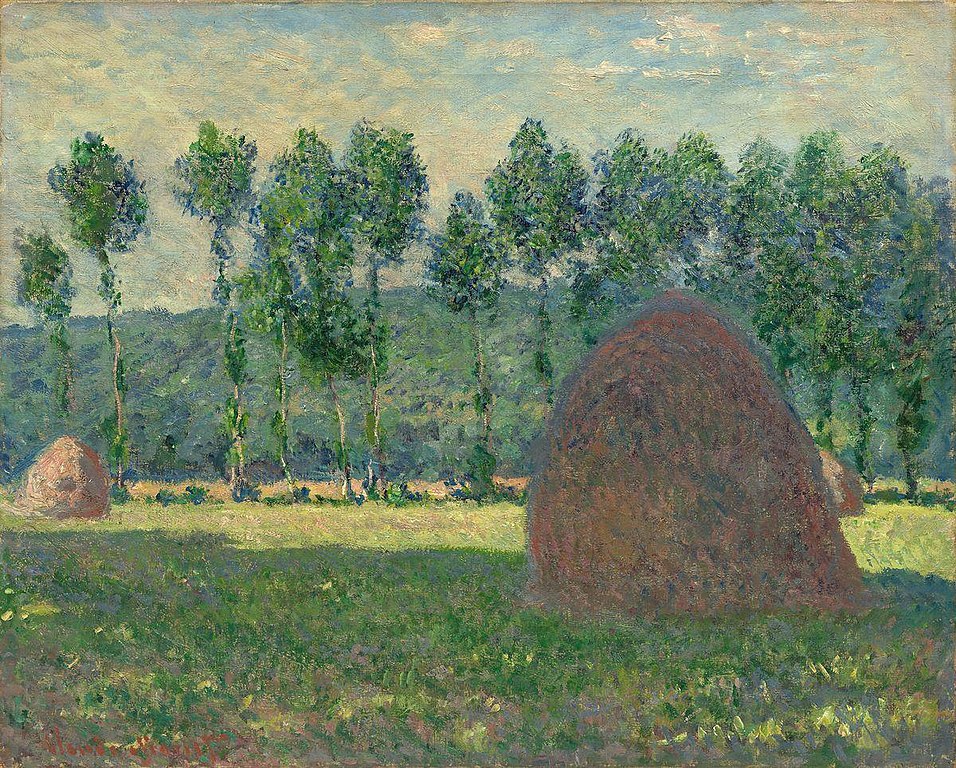

| Claude Monet, Haystacks at Giverny (1889; oil on canvas, 64 x 81 cm; Moscow, Pushkin Museum) |

Monet, throughout his career, always remained consistent with his painterly approach. Starting, for example, with the 1865 work, the portrait of Camille Doncieux, the layout is decidedly traditional. The main subjects chosen later are then different: he likes to depict landscapes, architectural structures, from different points of view and thus through different lights, following the changes of the day. The subjects of his paintings are not particular characters; what is of interest is the whole, the crowd. In the work Boulevard des Capucines, he depicts the crowded life of a Parisian street, without dignifying the faces of the passersby or the carriages with importance. The intent is to capture the whole, quickly, before the image just seen disappears from the artist’s mind. His is a soft, fluid brushstroke. The evolution of his works is also associated with exhibitions with the Impressionist movement, an experience that ended in 1886 with the last group exhibition. Some of the most important works of the period in question, 1874-1886, are the aforementioned Impression: soleil levant, the portrait to Carolus-Duran of 1878, and Monet’s The Garden and House at Vétheuil (1880). Another characteristic of his painting is his frequent choice of large paintings; not all of them are, of course, but it is interesting how the artist exceeds, as early as the late 1960s, two meters in size in some canvases.

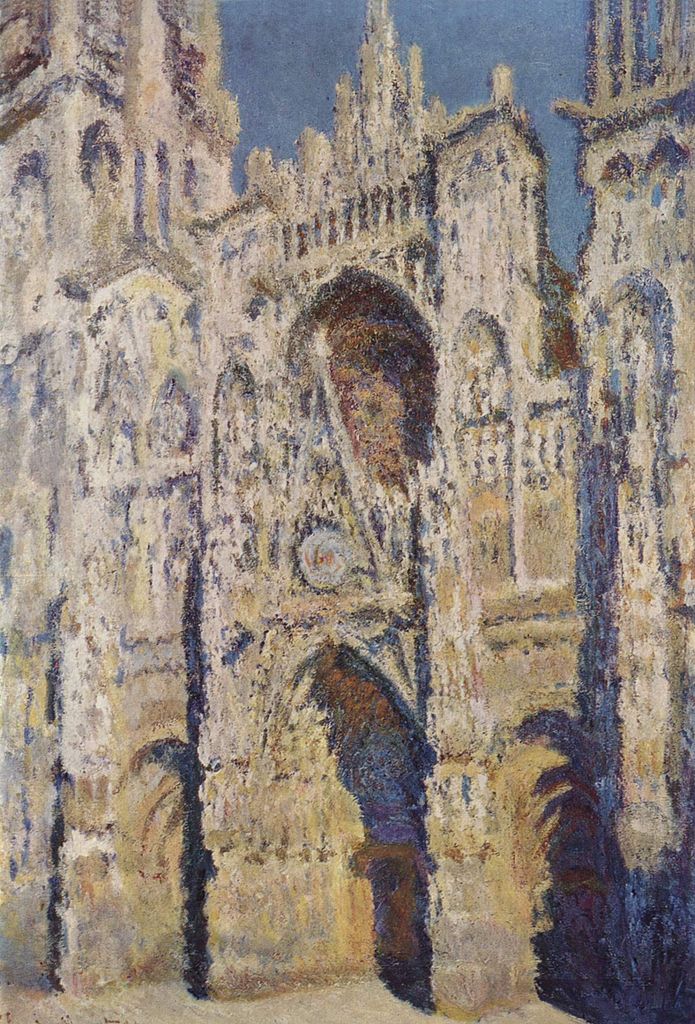

From the 1980s, Monet began to make painted works in series: in fact, the artist is interested in depicting same subject in different light conditions, thus painting at night or during the day, rain or shine, from one point of view or another. Central to this path is the series dedicated to Rouen Cathedral, dated 1892: its intention is to record all the changes in light and atmosphere, almost as if the artist wanted to reproduce the passage of time. In reality, the artist simply intended to document, through his canvas, the differences in brightness and variations in atmosphere, always keeping the same viewpoint or varying it slightly.

Monet juxtaposes pure colors, without blending them together. In 1884, during an Italian sojourn, he painted views of western Liguria, fascinated by the landscape, the splendid vistas and the colors: his Italian sojourn was also driven by a desire to study different light conditions, that of the warm Ligurian Riviera(read also an in-depth study of Monet’s “Ligurian paintings”).

In 1909 he wrote, “Every color we see arises from the influence of its neighbor.” About the Rouen Cathedral series he states that he “... portray the way his eye sees the cathedral.” Important to Monet is the role that perception plays: how the artist sees something, and then reproduces it on canvas. Each painting is thus different from another, because the eye perceives its surroundings in ever different ways, sensitive in turn to changing climatic conditions. This is a key concept, later taken up in the early 20th century by the abstractionists.

Monet’s works of the Giverny period were conditioned by the illnesses that affected the artist. The Water Lilies, the last famous series, were for a long time associated with the eventual madness of the ailing artist before he died. In reality, the water lilies themselves, long misunderstood, are strained toward a new style, modern, as foretold earlier, almost abstract, innovations essential to twentieth-century art. Water lilies are water flowers that reflect their own image in different ways, depending on the light; this is what intrigues the artist. Perspective is completely nullified here: the water lilies occupy space, with no distinction between foreground or background. The brushstrokes seem to be increasingly rapid, in order to capture the moment. The Water Lilies series, begun in 1897, then interrupted and resumed starting in 1914, is the most experimental of the late phase of Monet’s career, with some elements that almost seem to align with the emerging abstractionism ( Vasily Kandinsky’s first abstract works date from 1910): in some of the paintings the viewer sees only the water and the water lilies, without the viewer therefore having any points of reference. The artist thus leads the viewer into an almost fantastic world, where the only real fact is the presence of the water lilies, and the landscape appears reflected in the water, and therefore in a certain way unreal and dreamlike.

|

| Claude Monet, Garden at Bordighera (1884; oil on canvas, 65.5 x 81.5 cm; St. Petersburg, Hermitage) |

|

| Claude Monet, Rouen Cathedral in Full Sun (1894; oil on canvas, 107 x 73 cm; Paris, Musée d’Orsay) |

|

| Claude Monet, Pink Water Lilies (1898; oil on canvas, 81.5 x 100 cm; Rome, National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art) |

In Italy to see paintings by Monet you must go to the Galleria d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, where Pink Water Lilies from 1898 is preserved (it is one of the few Italian museums where Monet’s works are found). To see other works, a visit to some museums in France is recommended: in Paris, the painting Impression: soleil levant is kept at the Musée Marmottan Monet; at the Musée de l’Orangerie, the Water Lilies series, donated by the artist, is on display. The series The Cathedral of Rouen can be seen at the Musée d’Orsay (the main museum of reference for the Impressionists’ works, where many of Monet’s works are also kept), along with other works such as Women in the Garden of 1866-67 and The Poppies of 1873.

Also in France, at the Claude Monet Foundation in Giverny, it is possible to visit the house and gardens. Fortunately for fans of Impressionist art, exhibitions on Monet are often organized here in Italy, giving the opportunity to see both paintings held within private collections and through loans from the museums listed above.

|

| Claude Monet. Life and works of the father of Impressionism |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.