Mark Rothko (Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz, in Latvian Markus Rotkovičs; Daugavpils, 1903 - New York, 1970) was one of the leading exponents ofabstract expressionism, known for his color field paintings made between 1949 and 1970: They were, as will be seen, paintings in which the artist used a single color (or a very narrow range), rectangular in format, representing probably the most intimate declination of the expressive current that developed in the United States of America after World War II and had among its leading exponents artists such as Jackson Pollock, Wllem de Kooning, Philip Guston, Arshile Gorky, Helen Frankenthaler, Cy Twombly, Joan Mitchell, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hofmann and others.

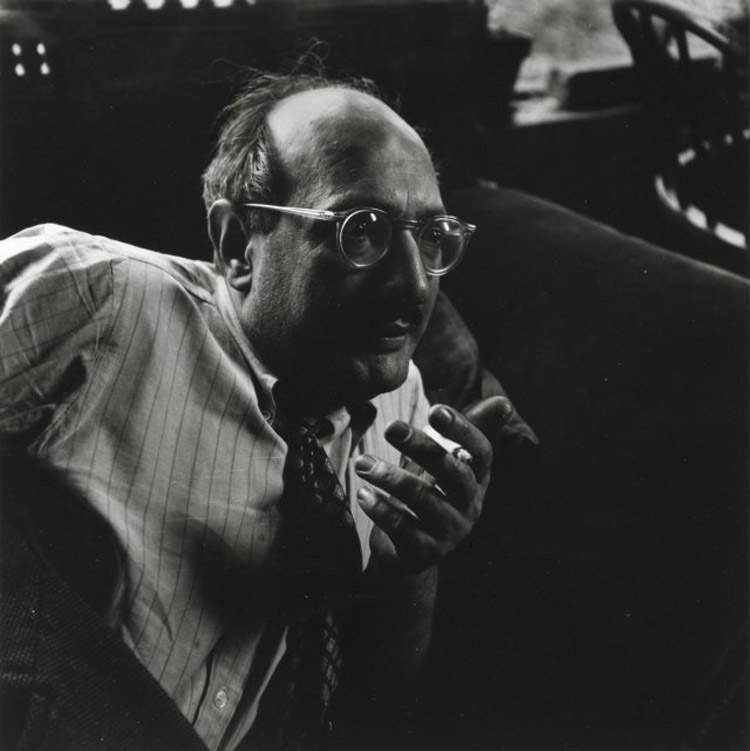

A Latvian-born artist, he left Russia (at the time he was born, the Latvia where he was born was part of the Russian Empire) at the age of ten along with his family to emigrate to the United States, settling in Portland, Oregon. Rothko’s works, and in particular his Color field paintings, convey the restlessness and tragic sense of existence that always accompanied his life, right up to the last moment (the artist in fact died by suicide), and this despite his achievements. He still led a rather modest and withdrawn life, although he was well inserted in the cultural and artistic circles of his time and was not an outcast. His paintings experienced staggering increases in prices after his death, so much so that today Rothko is one of the artists whose auction prices reach the highest values: it is not unusual for a Rothko painting to reach figures in the tens of millions of dollars.

Believed to be the most lyrical of the Abstract Expressionists, with paintings bordering almost on mysticism, Mark Rothko was convinced that art was “an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take the risk” (so he wrote in his Manifesto published on June 13, 1943 in the New York Times). The function of artists, Rothko continued, is to “make the public see the world in our way, not in their own.” And about the. content of paintings, the artist emphasized that “it is a widely accepted opinion among painters that it does not matter what you paint as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is nothing better than a good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial, and only that subject which is tragic and timeless is valid. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.”

Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz, in Latvian Markus Rotkovičs, was born in Daugavpils, Latvia, on Sept. 25, 1903, to Yakov, a pharmacist, and Anna Goldin, in a well-educated family of Jewish descent and secular beliefs. Rothko, the last of four siblings, nevertheless studied Talmud after his father returned to embrace the family religion, and at the age of ten, together with his family, he emigrated to the United States, and to be exact to Portland, Oregon. Yakov, however, died a few months after arriving in America: the event was traumatic for the family and left the Rothkos without income. Mark, too, was therefore forced to work as a young boy, selling newspapers (his father’s death, moreover, turned him away from religion). After finishing school in Portland and learning English (his fourth language: he was fluent in Latvian, Russian, and Yiddish) he began studying at Yale University in 1921, after which in 1924 he moved to New York to enroll in the Art Students League, where he studied with George Bridgman and Max Weber. In 1929 he began his job as a children’s painting teacher at the Center Academy of the Brooklyn Jewish Center, a position he held for twenty years.

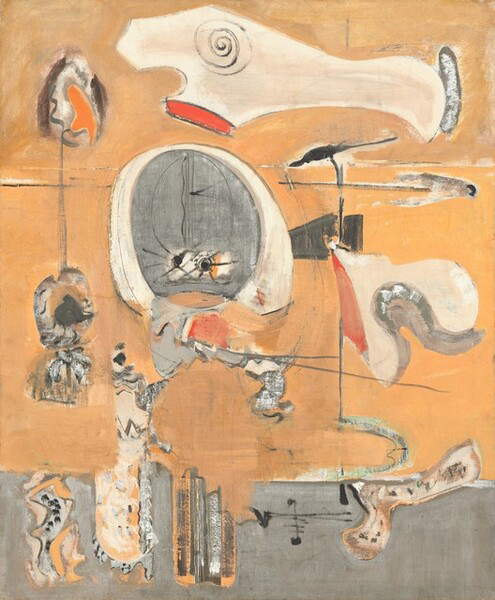

At the same time Rothko had begun his career as a painter: in 1928 he exhibited at the Opportunity Gallery, showing works on which depicted gloomy interiors and urban scenes, which received favorable feedback from critics and colleagues. In 1932 he met and married Edith Sachar, a jewelry designer. In the 1930s he met Milton Avery, a painter who convinced him that the idea of making a career as an artist was entirely possible for Mark Rothko. Successes were not long in coming: in 1933, in fact, Rothko held his first solo show at the Museum of Art in Portland and shortly afterward replicated in New York, at the Contemporary Arts Gallery. In 1935 he joined Ilya Bolotowsky, Ben-Zion, Adolph Gottlieb, Louis Harris, Ralph Rosenborg, Louis Schanker and Joseph Solman to form The Ten (“The Ten”) group, whose goal was to react to traditional painting. In 1938 he finally succeeded in obtaining American citizenship, and two years later, concerned about the spread of anti-Semitism even in the United States, he changed his name from Markus Rothkowitz to Mark Rothko (he avoided shortening it to “Roth” because Roth is another surname of Jewish origin). During the same years, his style, initially heavily influenced by Impressionism (Rothko painted mainly scenes of city life), began to evolve towardabstraction, in a progressive manner. Between the late 1930s and 1946, his paintings reflected his interests in themes such as Greek mythology and primitive art, with cues drawn from the works of Joan Miró and André Masson (Rothko was in fact drawn to the Surrealist theory ofpsychic automatism, which he experimented with to begin creating his first abstract forms). His “surrealist” works were first shown at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in New York in 1945. He had divorced his wife the year before and remarried Mary Alice Beistle in 1945.

By 1947 Rothko had also ended his “Surrealist” experience to give himself to non-objective compositions. Dating from the early 1950s was the elaboration of the Color field paintings, works Rothko arrived at by painting two or three luminous rectangles with soft, blurred edges, suspended as if floating. On the elaboration of the new poetics the knowledge of the abstract art of Clyfford Still, one of the first abstract expressionists, had a decisive impact. In 1948 he founded the Subjects of the Artist School in New York together with Robert Motherwell, William Baziotes, Barnett Newman and David Hare: here, Rothko taught and participated in publications. His art in the meantime had begun to know international fame, so much so that in 1950 he decided to embark on a trip to Europe (the thing that impressed him most were the Beato Angelico frescoes in San Marco in Florence, because of their spiritual charge that Rothko felt was very close to his own sensibility), while his exhibitions began to be held in Europe and Asia. On December 30, 1950, his daughter Kathy Lynn was born. In 1954 he exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, and in 1958 he got his first major commission, for a series of paintings for the Four Seasons restaurant, which would become one of his most important works (the Seagram Murals, so known because the restaurant’s location was in the Seagram Building). In 1958 he traveled to Europe again, and in 1961 he waited for the mural for Harvard University’s Holyoke Center, after which he worked on the Houston Chapel from 1964 to 1967, producing fourteen canvases that constitute his most famous masterpiece(read an in-depth look at Rothko’s Houston Chapel here). By 1963, meanwhile, his second son, Christopher, had been born. In 1970, as his depression deepened, the artist took his own life: he was found dead on Feb. 25, 1970, by his assistant Oliver Steindecker, with a conspicuous cut on the artery of his right arm, and cut short by a barbiturate overdose. He left no suicide note.

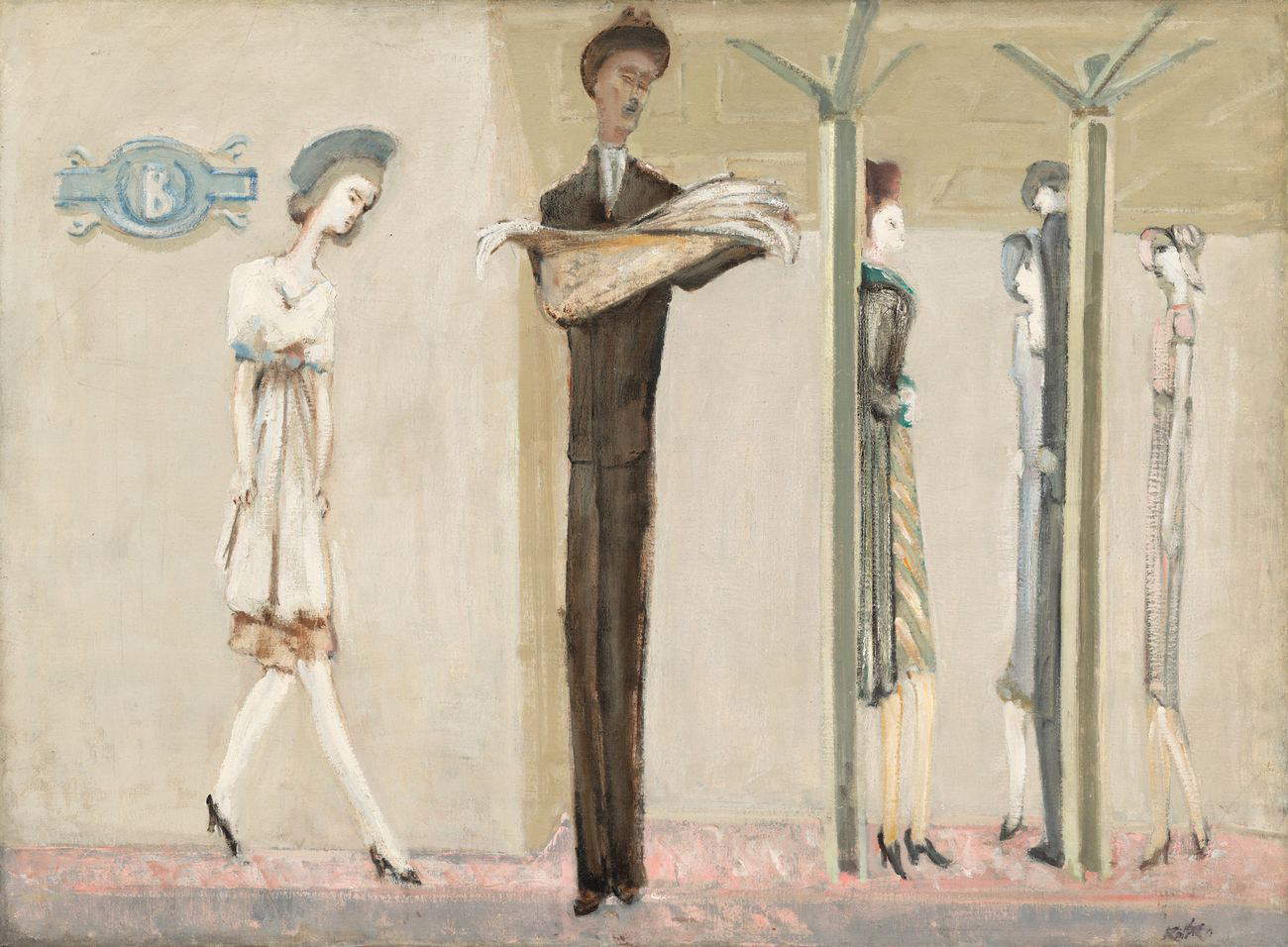

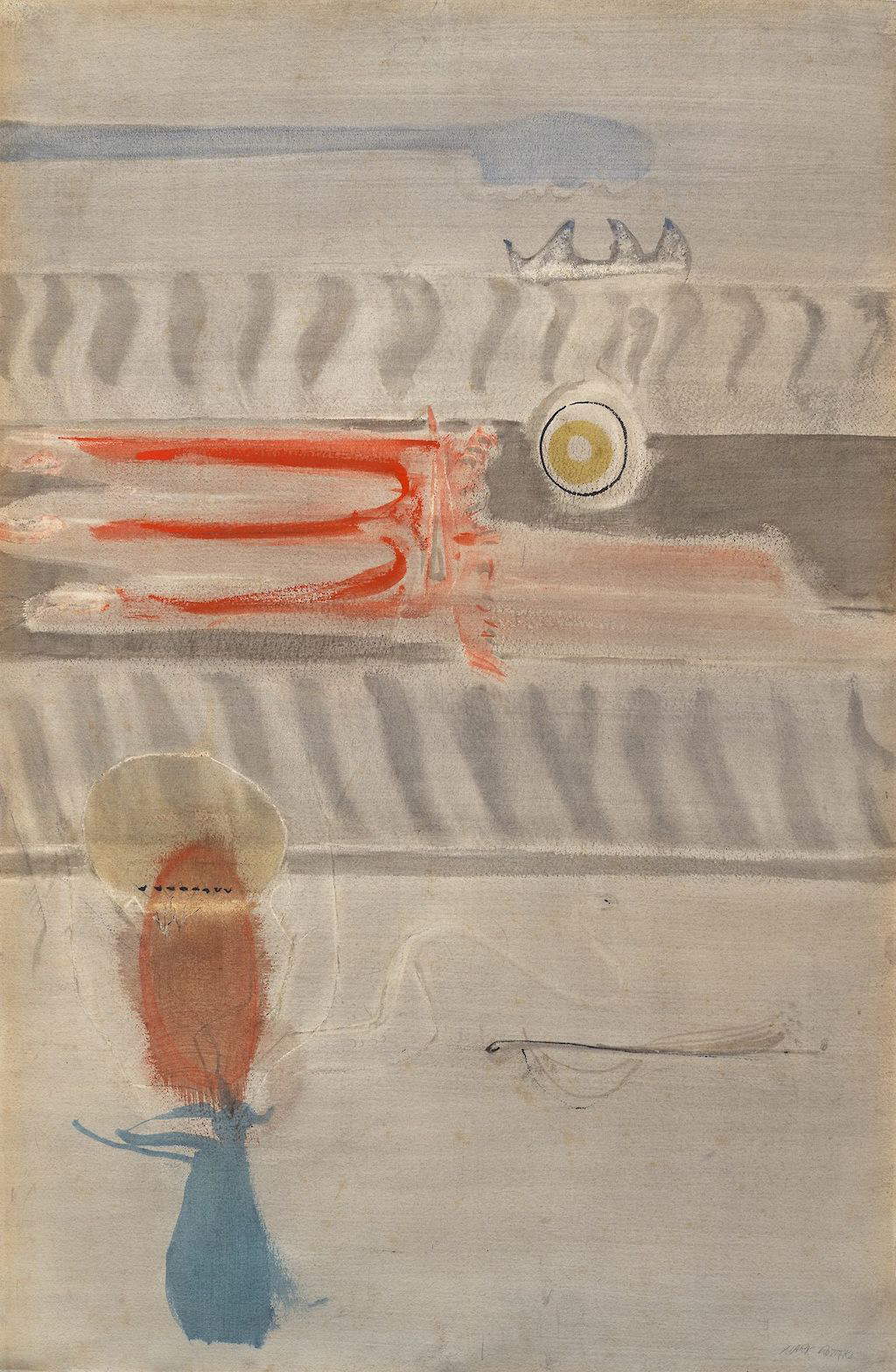

Three clearly delineated phases can be distinguished in Mark Rothko’s career: one that runs through 1940, a second that runs from 1940 to 1949, and a third that runs from 1949 onward. In the first phase, the artist practiced a figurative painting that took its cues from bothImpressionism andExpressionism: in the early years Rothko devoted himself primarily to scenes of urban life, exaggerating the tension and eeriness of the scenes, as seen in Underground Fantasy of 1940, a scene set in a subway where the characters are eerie, wiry-looking figures hovering near pillars resembling themselves. With these works, Rothko probably wanted to express on canvas the concerns of the Great Depression-era United States. In the 1940s his painting changed by taking in elements drawn from theSurrealist avant-garde and becoming interested in myth. The change of direction was put in black and white in the Manifesto published in 1943 in the New York Times: the paintings of this period refer to famous episodes from mythology and ancient literature (for example, the 1942 Sacrifice of Iphigenia or again the 1946 Sacrifice preserved at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice), but they are nevertheless compositions already strongly oriented towardabstractionism. Rothko’s intention, in fact, was not to provide a representation of the episode, but rather to suggest its atmosphere. The figures, executed with almost pure forms, colored with stretched and shaded backgrounds, as well as the division into horizontal bands and the single-color background, anticipate the color field paintings of the last phase of his career. At this stage it is above all Joan Miró who is Rothko’s main point of reference, as is easily seen in Sea Fantasy of 1946.

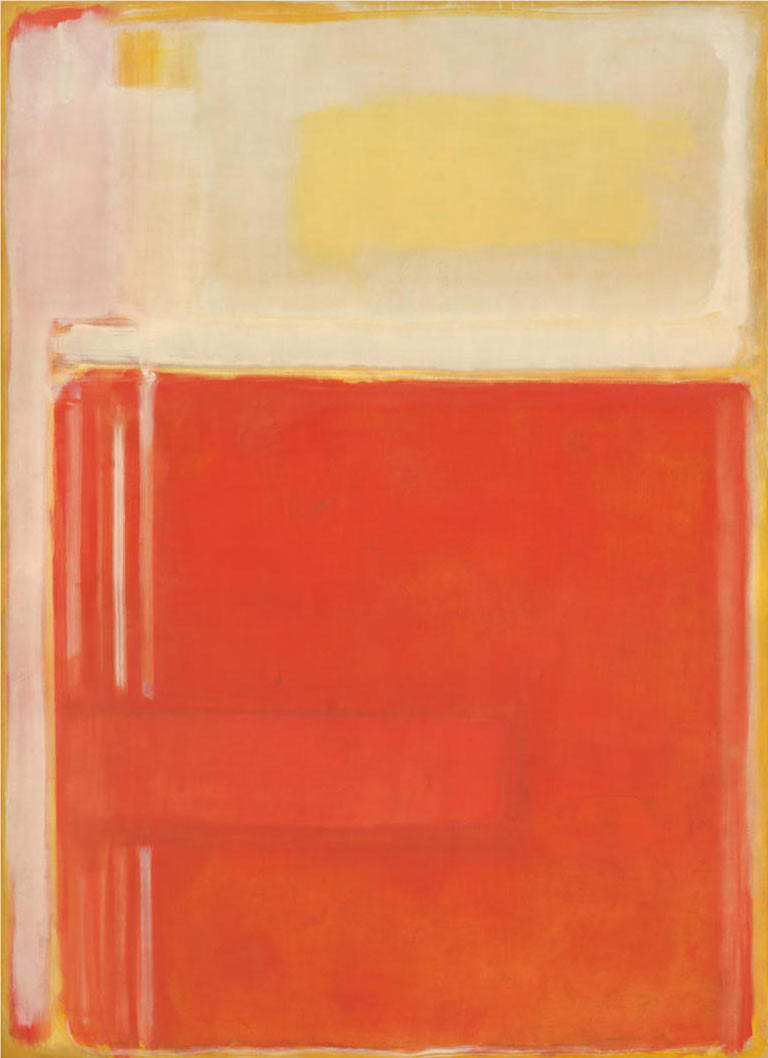

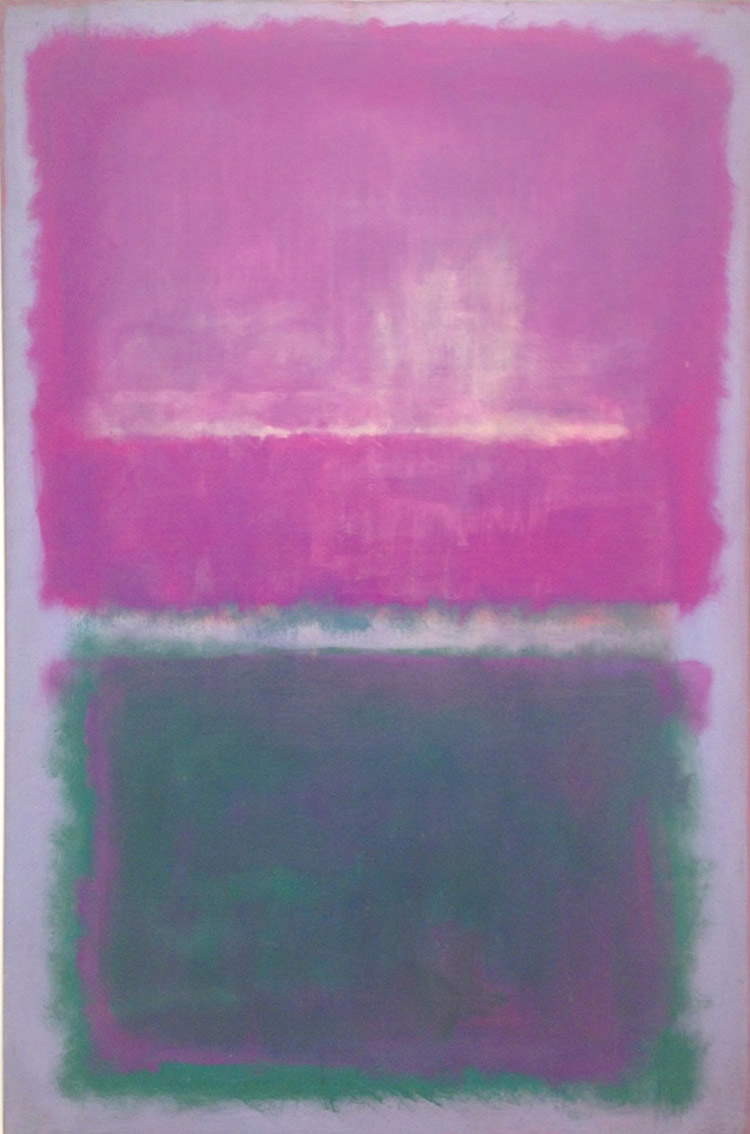

The elaboration of the Color field paintings, made with rectangular fields arranged over monochrome backgrounds and with blurred and evanescent edges, dates from the late 1940s. Thus began the so-called “classical phase,” since it is Rothko’s best-known manner and the one most appreciated by the public. The artist stopped giving conventional titles to his works and often even resisted those who asked for explanations, as he feared the words would damage the public’s imagination. Beginning in 1950, the color field paintings settled down: from a minimum of two to a maximum of four rectangles on a monochrome background. From this point on, Rothko would work exclusively in this way, varying only the choice and combinations of colors. Although the artist hardly explained his works, their reason must be sought in the symbolic, metaphysical and intimate potential of these compositions. Indeed, it was important for Rothko to bring the viewer to a state of intimate contemplation. And to do all this, the artist believed that the large format was indispensable. “I paint large paintings,” he had this to say, “because I want to create a state of intimacy. A large painting is an immediate act: it takes you into itself.” Thus, the painter’s idea was to emotionally engage the viewer, and if someone went so far as to cry in front of one of his paintings, then the artist had hit the mark, for the audience in that way felt the same experience that he had felt painting the works.

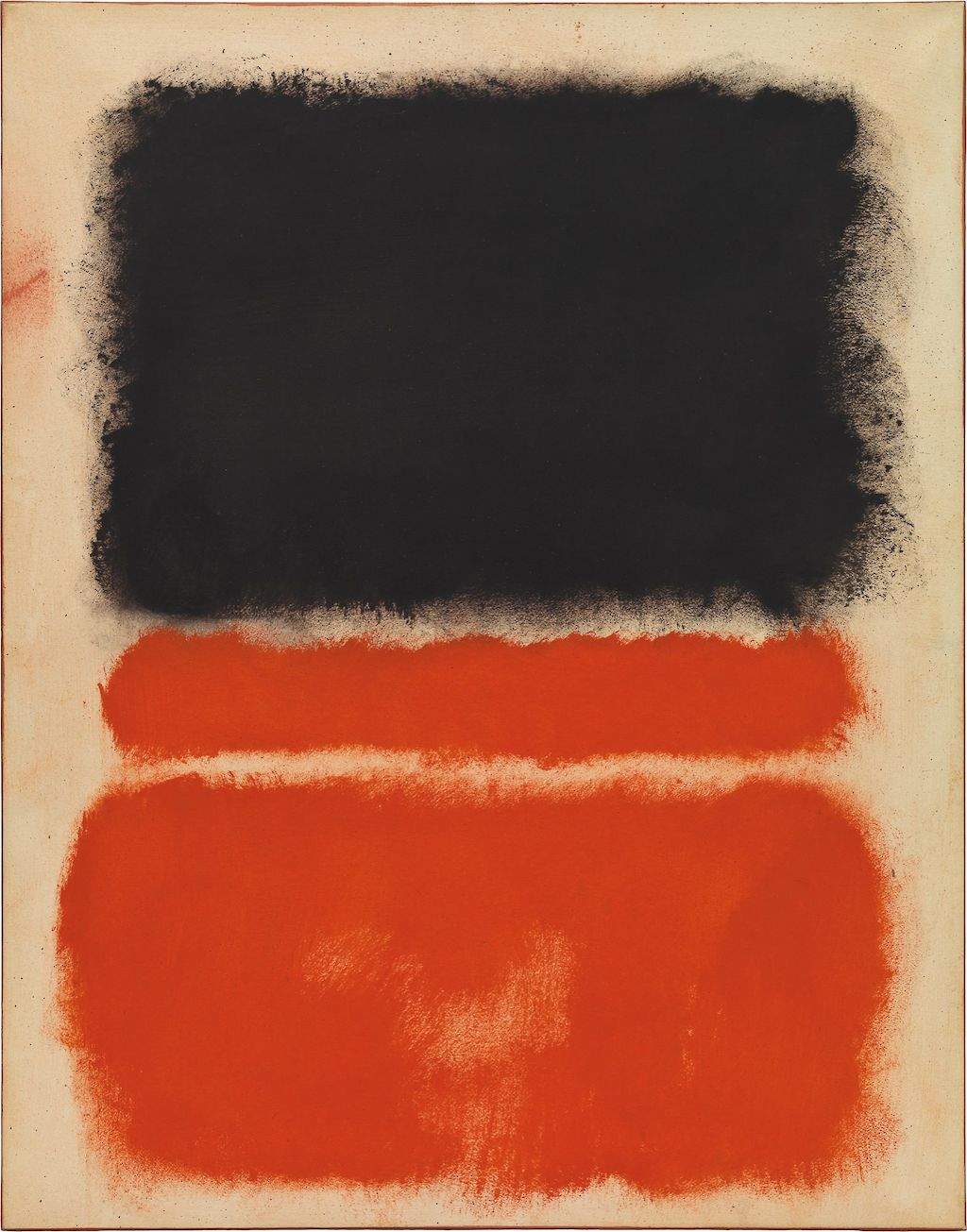

And for that very reason, Rothko decided not to deliver the paintings he had been commissioned to paint for the Four Seasons: in fact, he felt that such a place was not suitable for viewing his works. Today, paintings from the cycle can be found in several museums around the world. The artist liked the idea of finding a permanent setting for the works so that they could be shown in one setting, all together, to immerse the public in his art. As he worked on the murals, Rothko increasingly focused on a darkened palette (which would later become characteristic of the last decade of his career) of reds, browns, and blacks. The dream would not be realized at the Four Seasons, but rather at the Houston Chapel (now Rothko Chapel: once a Catholic house of worship, today it is nondenominational), where, commissioned by collectors John and Dominique de Menil, he painted works with the goal of filling the space, with the specific request that they be site-specific. There are fourteen paintings in the chapel: on three walls are three triptychs, while the remaining five display individual paintings. They are works with the dark tones typical of the last phase of Rothko’s career, very subtle, made with the purpose of creating a precise continuity between work and environment and to enhance the spirituality of the chapel. Works that, in essence, lend themselves well to meditation and contemplation, the summa of the American artist’s experience.

Mark Rothko’s works are held in museums around the world, although the major masterpieces are in the United States. Significant cores of works by the American artist can be found at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., MoMA in New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Guggenheim, MOCA in Los Angeles, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Portland Art Museum, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The Rothko Chapel in Houston can be visited and, as mentioned above, houses fourteen site-specific paintings by the artist thus representing a unique way to get to know him. Outside the United States, one can find Rothko’s works at the Tate in London, the Guggenheim in Bilbao, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Fondation Beyeler in Basel (the Swiss museum has one of the most significant Rothko nuclei outside America and in 2020 organized a significant exhibition on the artist), as well as at the Rothko Center in Daugavpils, Latvia, his hometown, which has established an institute named after him where, in addition to a permanent collection displaying some of his work, exhibitions and meetings are held regularly.

Although Mark Rothko loved Italy, there are no museums in our country that exhibit works by Rothko, except for the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice where two works can be found: the 1946 Sacrifice and Untitled (Red) from 1968.

|

| Mark Rothko, life and works of the most intimate abstract expressionist |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.