A free and provocative spirit, Piero Manzoni (Soncino, 1933 - Milan, 1963) was an artist of inexhaustible energy and creativity who always sought to push the potential of art to its limits. Through his work, the Cremonese artist was always able to make people talk about him, impressed visitors, gallery owners, and collectors, and won his place as an icon in Western culture.

Milan was the setting of his life: here the artist trained, studied, worked and had contacts with the most innovative trends of the time, although he often went to Albissola, in Liguria, a destination frequented by many artists. Initially he frequented artists belonging to the Nuclear Group, including Enrico Baj and Lucio Fontana, and then the German group Zero. With the painter Enrico Castellani he established a great association, which led the two artists to found the famous magazine Azimuth and the gallery of the same name. His art is the visual expression of an idea, it is the gesture that testifies to a presence; his radical insights and profound mental elaborations enabled the artist to become world famous.

|

| Piero Manzoni |

Piero Manzoni was born on July 13, 1933, in Soncino, a small town in the province of Cremona. The son of Egisto Manzoni, Count of Chiosca and Poggiolo, and Valeria Meroni, from the family of the historic Filanda Meroni silk mill, Manzoni received an aristocratic and Catholic upbringing, spending his childhood and youth between Soncino and Milan. After graduating from high school, Piero enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart in Milan in 1951. These were the years in which he developed his interest in reading, concerts, cinema and theater. In 1953 he began to devote himself more steadily to painting, attracted and inspired by the Ligurian landscape of Albissola, near Savona, where he often went on vacation with his family. Manzoni in 1955 left the Faculty of Law to switch to the Faculty of Philosophy, so he moved to Rome, but at the end of the year he returned to Milan. He began to frequent the Milanese artistic milieu by visiting the studios of artists Roberto Crippa and Giani Dova, exponents of the Spatial Movement, promoted by gallery owner Carlo Cardazzo and spurred on by artist Lucio Fontana, whom, by the way, Manzoni probably knew because his parents were family friends.

In 1956 Manzoni produced works with imprints of objects, with oil and heterogeneous materials on canvas . In the same year he participated in the “IV Market Fair. Exhibition of Contemporary Art” at the Castello Sforzesco in Soncino in which the painter exhibited Papillon Fox and Domani chi sa, which with their strong tones fascinated and attracted the attention of all visitors. In Milan, on the other hand, he exhibited at Galleria San Fedele participating in the “San Fedele Painting Prize 1956.” With Ettore Sordini, Camillo Corvi-Mora and Giuseppe Zecca he published his first poster, Per la scoperta di una zona di immagini, the first of a long series of posters. The first group exhibitions began in 1957: Manzoni exhibited on January 15 at Galerie 17 in Munich, organized by Luca Scacchi Gracco with artists Lucio Fontana, Enrico Baj, Bruno Munari, Arnaldo Pomodoro and others. A few months later another group show in Milan allowed him to meet the artist Dadamaino, who collaborated on the activities of Azimuth, a magazine founded by Manzoni and Enrico Castellani. On May 29, the exhibition Manzoni, Sordini, Verga opened at Galleria Pater in Milan, accompanied by an introductory text by Fontana. Manzoni also began to exhibit in contexts with “historicized” artists, such as the Fifth Art Market Exhibition at Galleria Schettini in Milan.

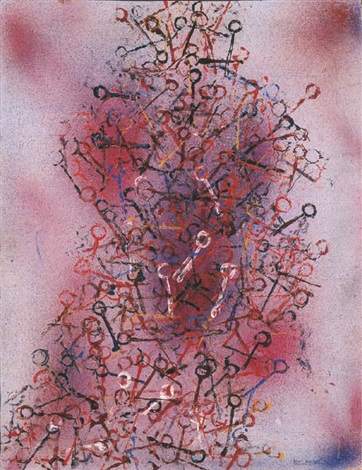

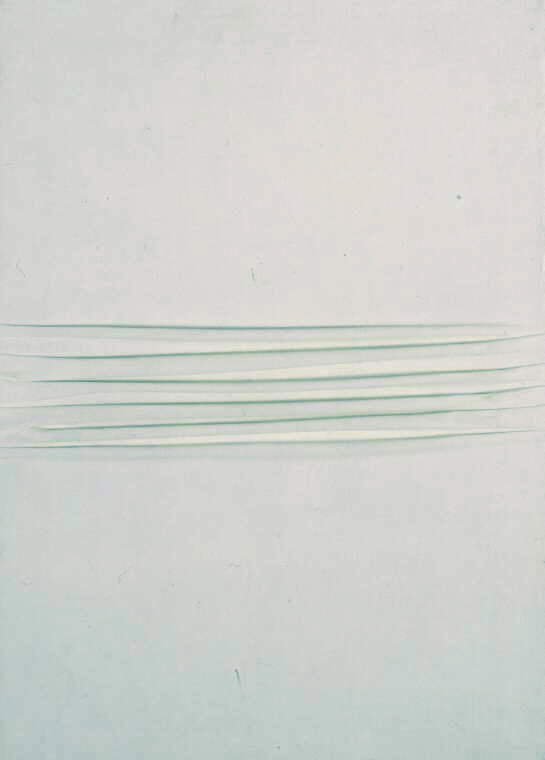

Toward the end of 1957 he painted his first "white paintings," initially with chalk and then with kaolin and canvas. In the following months the artist titled all the white paintings Achrome . In 1958 he continued the production of his very famous Achorme but also executed the first Alphabet with ink and kaolin on canvas. At the Fontana, Baj, Manzoni exhibition at the Bergamo Gallery in Bergamo and then at the Circolo di Cultura Gallery in Bologna, the painter exhibited his “white paintings” for the first time.

It was in the summer of 1958 that Manzoni made his first trip to Holland, where he befriended artists such as Gust Romijn and gallerists such as Hans Sonnenberg. It was in Holland that he held his first outdoor solo exhibition, Piero Manzoni Schilderijen, in Rotterdam (September 10-29, 1958). Manzoni’s artistic activity became increasingly frenetic: however, between intense hours of work and study, there was no lack of travel and long evenings made up of alcohol and the exchange of ideas among friends.

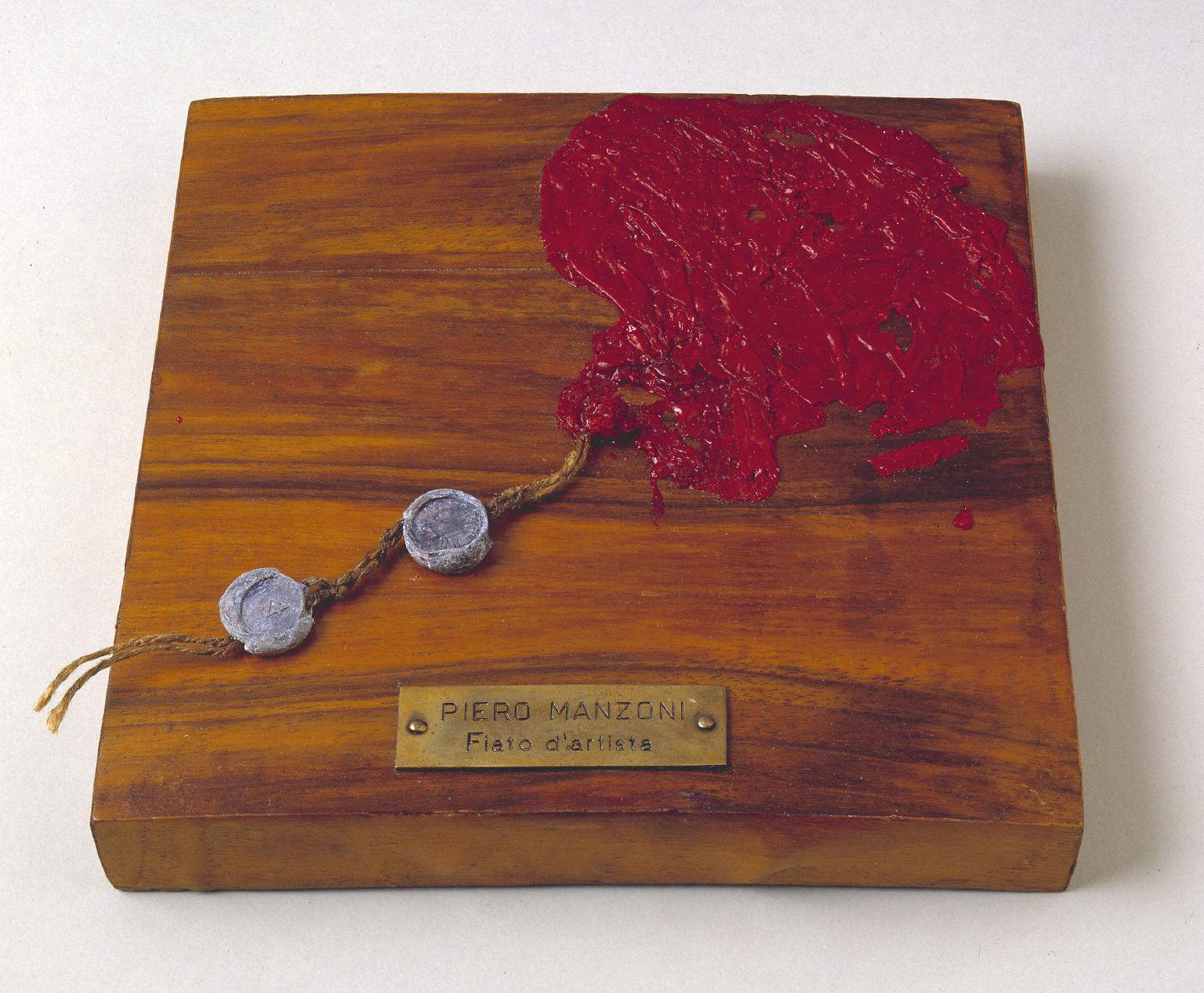

In 1959 the Achromes with sewn canvas began. In Rome he met artists and gallerists of the new avant-garde such as Tano Festa, Mario Schifano and Franco Angeli and the intellectual, poet and critic Emilio Villa, who would write a text on Manzoni’s work. The first production of Lines took place in 1959, and in September of that year the first issue of the magazine Azimuth, founded and edited by Manzoni and Castellani, was published. Writings by intellectuals and critics, such as Gillo Dorfles, appeared in the magazine , works by artists such as Fontana, Yves Klein, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were reproduced, as well as poems by Edoardo Sanguineti, Nanni Balestrini and others. After the magazine, Castellani and Manoni rented a basement on Via Clerici in Milan, where they founded the Azimuth Gallery, a self-managed space like the magazine of the same name. Manzoni’s style became more provocative: in fact, the artist made Sculpture in Space, or a pneumatic sphere suspended si a jet of water, but also Fiato d’artista, balloons inflated by Manzoni, sealed and fixed on a wooden base. At the Azimuth gallery he presented one of his most famous performances, The Consummation of Dynamic Art in Public - Devouring Art, in which the artist signed with his thumbprint some hard-boiled eggs, which were then distributed to the public and eaten. From 1961 he began to sign Living Sculptures then “certified” by Cards of Authenticity and May made the famous ninety boxes of Artist’s Craps, first exhibited at the Pescetto Gallery in Albissola. Recent exhibitions include the Monocroma Exhibition at the Il Fiore Gallery in Florence in January 1963 and a few days later inaugurated a solo show at the Galerie Smith in Brussels. On February 6, 1963, Piero Manzoni died prematurely in his studio in Milan, aged only twenty-nine, of a heart attack.

|

| Piero Manzoni, Domani chi sa (1956; oil and wax on masonite, 89.5 x 69.5 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Achrome (1958; kaolin on canvas, 50 x 30 cm; Genoa, Museo d’Arte Contemporanea di Villa Croce) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Alphabet (1958; photolithograph, 50 x 35 cm) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Line of Infinite Length (1960; wooden cylinder and paper label, 15 x 4.8 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

Piero Manzoni’s works impressed and elicited a wide variety of comments from the very beginning of his career. In fact, the artist’s provocative and irreverent nature accompanied him throughout his life. The two early works Papillon Fox (1956) and Tomorrow Who Knows (1956), which he presented at the “IV Market Fair. Contemporary Art Exhibition,” present ambiguous tones that nevertheless attracted much interest from visitors. In these early works the artist’s attitude was Surrealist, thus, psychoanalytic principals, expressive and gestural automatisms that were also in tune with the Nuclear Art Movement, which the artist joined in 1957. A particularly important year for the artist was 1957 as it presented itself as a year of great artistic experimentation but also questioning of certain principles and method. In fact, if in the very first works the figurative aspect was slightly present, in 1957 the Cremonese painter moved closer and closer to material, more “abstract” conceptions, and then landed at the end of the year to his famous white monochromes. The painter’s “white paintings” would not be called Achrome until 1959. The premises of Achrome were the “area of freedom” or the “authentic and virgin zone,” heralded in the text of his first debut manifesto For the Discovery of an Image Zone. Achromes were made systematically by the painter, who used heterogeneous materials and techniques. The different materials used allowed him to delve even deeper into the concept of “genesis” of the work of art and of art making more generally. The work does not illustrate a specific subject, nor does it refer to anything beyond the frame but is self-referential . The artist’s aim was to deprive the work of all narrative content and by eliminating color the only subject of the painting became matter .

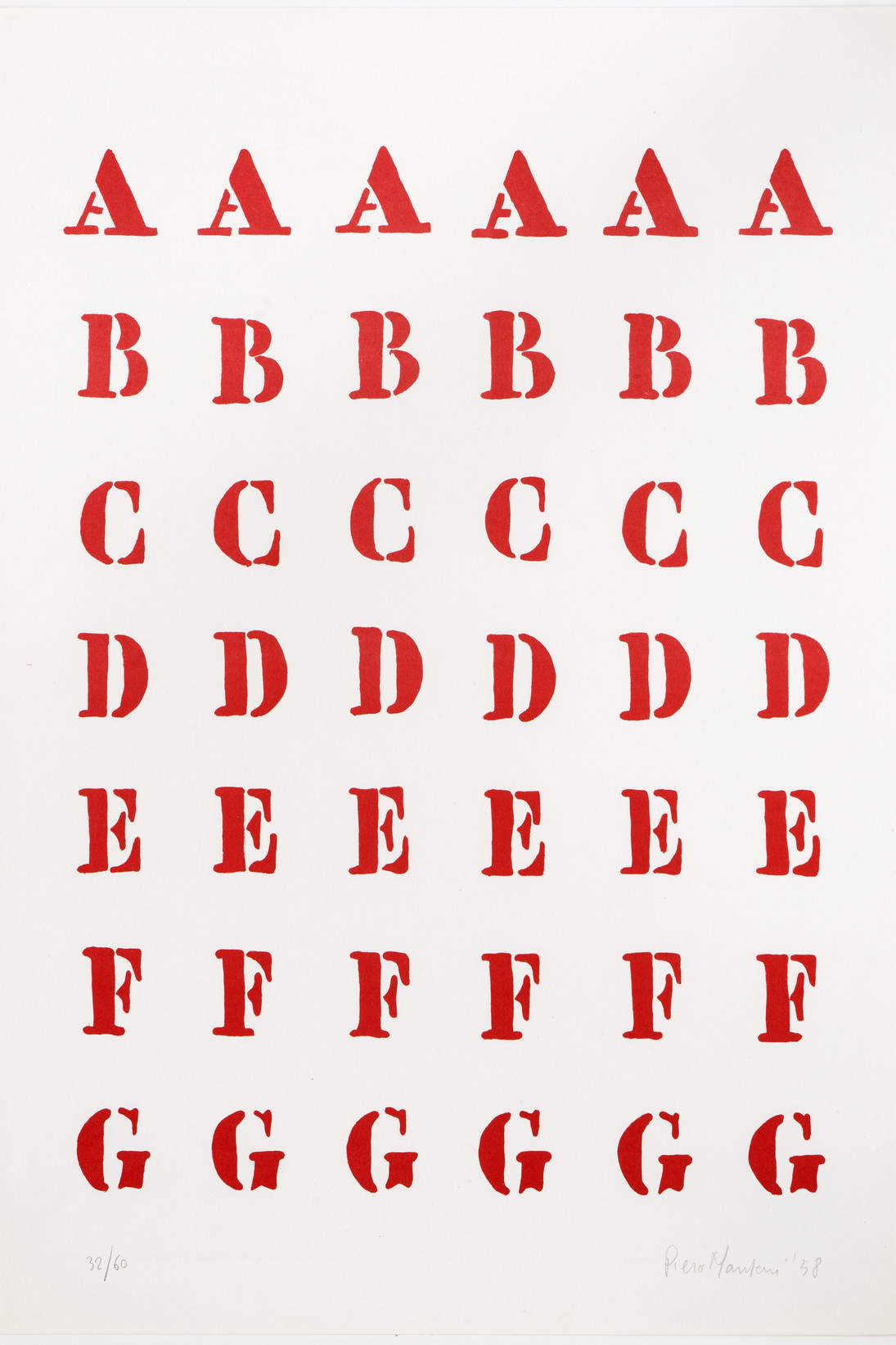

The artist also sought universal signs, which led him in 1958 to create his first Alphabet . The work was made with ink on canvas and repeats the letters “abcd” in three parallel columns, with impersonal, objective and cold value. The project of searching for universal signs took a more organic form when in 1962 he elaborated 8 tables of ascertainment, in a “folder” format in which sixty numbered copies appeared with eight photolithographs published by Vanni Scheiwiller and with a preface by Vincenzo Agnetti . The lines were considered by Manzoni to be one of his most important discoveries. The first Linea was made in the spring of 1959 and consists of a dark rectangular sheet on which a dark line is drawn. From the summer of 1959 he made lines on rolls of paper then rolled up and closed into cylinders on which is a label bearing the length, date and signature of the artist. These were the first works to break out of the two-dimensionality of the painting. In the work Line of Infinite Length (1960), exhibited at the Azimut Gallery, as well as in the earlier ones, the label on the cylinder shows the length in centimeters of the line made by the artist, however, the line does not exist as it is pure concept. Visitors to the exhibition bought not the line, but the idea . As the artist himself had this to say in the text Free Dimension: “composition of form, forms in space [...], all these problems are foreign to us: a line can only be drawn, very long, to infinity [...]. The only dimension is time.” The 7200 m Long Line was made in 1960, then sealed in a cylindrical container of zinc and lead. According to the artist’s intentions, this was the first in a long series of lines that were to be buried in the world’s largest cities and whose sum total was to be that of the earth’s circumference. This was the artist’s extreme attempt to give art the possibility of release from the canvas, the possibility of a ’total extension .

After the Lines, Manzoni elaborated other “three-dimensional” works such as Corpi d’aria (1959), which he called "pneumatic sculptures." In a wooden box, along with a sheet of instructions, were placed a white balloon to be inflated and a tripod on which the air sculptures were then placed. Similar was Fiato d’artista (1960), which was a balloon inflated by the artist himself. The works were sold for 30,000 liras each. The balloons were inflated directly by the artist in the presence of the buyer, including the execution of the work in the price, and the value varied according to the amount of breath put into the balloon. The figure of the artist becomes central: the essence, in this case the breath, itself becomes creation, the moment it is decided that it should be Art. What counts, then, is the signature of the author and not the work itself. This was the idea that Manzoni ironically and provocatively criticized in each of his works.

At the Azimut Gallery in 1960 Manzoni presented one of his two most famous “performances,” namely Consuming the audience’s dynamic art, devouring art, where he offered visitors boiled eggs to eat, “signed” by the artist with his thumbprint. The work seems to be a ritual act of communion and consummation between artist, work and audience. There are several interpretations of the performance. The first is based on the mystical-religious reading and focuses on the symbolic nature of the food, as well as the ritualistic and sacramental aspect of the event. The second interpretation is based on the consumption of the egg understood as a potential negation of the commodification of the work of art. The latter reading allows the artist’s performance to be situated as a particular form of contestation of the official art system . A variant is Egg Sculpture (1960), eggs with the artist’s shell and fingerprint, kept in a small wooden box, numbered and filled with absorbent cotton, as if it were a relic. Manzoni, however, was not yet satisfied, for him art had to be total, it was not enough for him to “get out” of the canvas, now art had to live, so from January 1961 the artist signed people as works of art. Of the performance Living Sculptures there are many photos documenting the event, in these precious documents Manzoni signs people, then fitted with stickers certifying their artisticness. The red stamp means that the person will be a living sculpture until death, the purple stamp is similar to the red one but for a fee, the yellow indicates that only a part of the body is a living sculpture, and the green means that the person will be sculpture only in certain positions and attitudes. The last person signed was Umberto Eco.

In 1961 he made Basi magiche: a wooden pedestal that allows a person to become a work of art as long as the object or person stands on top of the structure. In 1961 Manzoni arrived at a radical insight, pushing the concept of art to its limits. It is a parallelepiped measuring one meter by eighty centimeters where the upside-down inscription reads Socle du monde, - socle magique no.3 de Piero Manzoni - 1961 - Hommage à Galileo. This is the base that, with the pedestal facing the ground and the upside-down inscription, holds the globe, people, culture and nature that become a work of art. Finally, one of Manzoni’s most provocative and disconcerting works is the famous Merda d’artista (1961), which follows almost a natural biological process, after Fiato d’artista and Consumazione delle uova: the painter “digests” the whole thing. The work was boxed in May 1961, in ninety numbered copies. This is the work that most of all conditioned Manzoni’s notoriety as a provocative and desecrating artist. Above the box a label reads “artist’s shit. Net content 30 gr. Preserved in its natural state. Made in Italy.” The top of the tin bears the artist’s number and signature. The important conceptual passage is the sale-certification, whereby the value of the work must correspond to the daily value of gold per gram. The series is thus critical reflection on the consumption and commercialization of art and more generally of consumer capitalist society. Piero Manzoni questioned the very meaning of artistic research, the role of the artist but also that of the public so with his always extremely provocative art he contributed to the renewal of the Italian art scene.

|

| Piero Manzoni, Air Bodies (1959; mixed media, various dimensions; Barcelona, MABCA) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Artist’s Breath (1960; balloon, rope, bronze and wooden base, 35 x 180 x 185 mm; London, Tate Modern) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Egg Sculpture No. 29 (1960; ink on egg, wooden box, 5.7 x 8.2 x 6.7 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Piero Manzoni, Artist’s Shit No. 3 (1961; metal box, 4.8 x 6.5 cm; Private Collection) |

The Piero Manzoni Foundation was established in Milan in 2008: here it is possible to see many of the painter’s works, and the institute also promotes historical-critical research on the artist as it preserves catalogs, photographs, invitations and valuable documents. In addition, the foundation collaborates with the Gagosian Gallery.

At the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome it is possible to see the Achromes of the 1960s. In Milan at the Fondazione Prada and the Museo del Novecento, Achrome (1958-1959), and Uovo scultura n.34 (1960) are preserved, respectively. A specimen of Merda d’artista (1961) is also preserved at the Museo del Novecento in Milan. HEART: Herning Museum of Contemporary Art, Denmark boasts of a substantial collection of Piero Manzoni’s works, including several Achromes, Linea lunga 7200 m (1960) and Socle du monde (1961), and Merda d’artista (1961). At the MoMa (Museum of Modern Art, New York) one can see the famous little box Artist’ s Shit (1961), which can also be seen at the Tate Modern in London, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and several other museums that hold examples.

|

| Piero Manzoni, life and works of the author of Merda d'Artista |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.