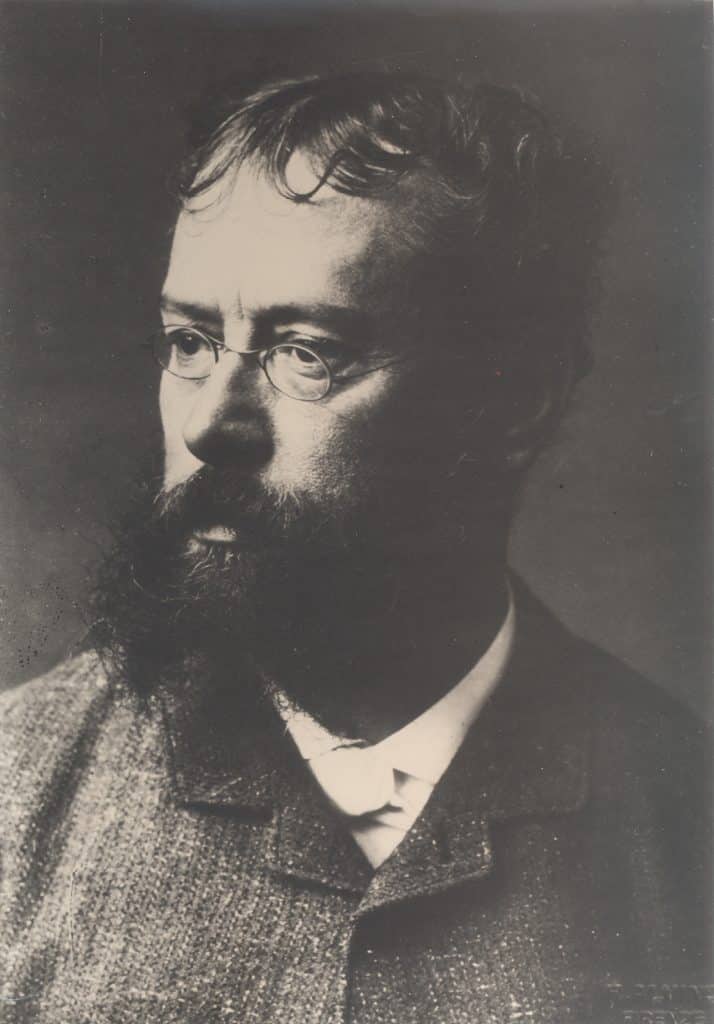

Telemaco Signorini (Florence, 1835 - 1901) was an Italian painter who was part of the Macchiaioli group, also proving to be one of the movement’s most fervent theorists. He was initially given the term “macchiajuolo” in a derogatory sense by newspapers. The painter’s sensitivity led him to present, in some of his canvases, situations of social hardship that caused a great stir at the time and contributed to his later fame.

Signorini, a leading exponent of the Macchiaioli, was also one of the group’s most open-minded and sensitive painters, and during his career he received criticism but also much praise. On the occasion of his participation in the 1898 Venice Biennial, the great art critic Vittorio Pica wrote of him, “I do not believe that there has been in Italy, in this half of the century, another artist who has fought academic traditionalism, conventional official teaching and the shopkeeping skills of prissy and pleasing art with greater constancy, with more complete disinterest, with more lively boldness than Telemaco Signorini. The entire existence of this valiant Tuscan painter and etcher, who still retains, despite his sixty-three years of age, all the battling boldness of his youthful years, was in fact nothing but an assiduous aspiration toward the new horizons opened up to the painting of the modern age, and a most fierce struggle against all sorts of reactionaries of art, in order to be right about whom the casual and witty pen and the Florentine biting tongue have often served him no less than the wise and sagacious brush.”

Telemaco Signorini was born in Florence on August 18, 1835, to Giovanni and Giustina Santoni. His father was an esteemed painter who worked at the court of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopold II, and he in turn wanted to direct his son Telemaco toward artistic studies. In 1852 Signorini enrolled at theAccademia delle belle arti in Florence, but soon manifested a clear rejection of the institution’s rigid training. He thus left the Academy in 1856 and began practicing outdoor landscape painting, along with other artists including Odoardo Borrani and Vincenzo Cabianca.Already in the previous year, 1855, a 20-year-old Signorini had begun to frequent the Caffè Michelangiolo, a lively artistic and literary meeting place where a group of artists united precisely by their intolerance of academic dictates, who would later unite under the name Macchiaioli, used to meet. Signorini, by nature, had a very pronounced dialectical and debating ability, so he often and willingly launched into articulate discussions with his colleagues. It is no coincidence that he is considered one of the theorists of the “macchia.” Meanwhile, he had traveled several times along northern Italy, in search of new stimuli to succeed in achieving the right balance in the contrast between light and shadow in his paintings. In particular, it was a stay in the Cinque Terre in Liguria that proved to be of great inspiration to him in his artistic endeavors.

Like other painters of his contemporaries, Signorini also enlisted and participated in the Second War of Independence in 1859. This was because the years of the Risorgimento, between the first and second half of the 19th century, were characterized by major revolutionary turmoil and, as a result, war conflicts erupted along the Italian territory, until the proclamation in 1861 of the Unification of Italy. Upon his return from military engagement, the artist produced several paintings on the very theme of life under arms, which were accepted at the Florence Academy Exhibition and were very successful among the public.

During the same period, however, his landscape works that were the result of the research he had done during his stay in Liguria(read more about Signorini in Riomaggiore here) were harshly criticized. In one of his writings we read verbatim, “Upon my return to Florence, I had my first works rejected by our Promotrice (Academy of Fine Arts in Florence) for excessive violence of chiaroscuro and was attacked by the newspapers as a macchiajuolo.” The newspapers intended to use the term “macchiaiolo” in a derogatory sense, but Signorini was intrigued by the term and proposed to the group of artists to use it as the name of their movement. In 1861 Signorini took a trip to Paris with other artist friends, and here he came into contact with Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and Constant Troyon, eventually becoming enraptured by the realism of Gustave Courbet. On his return to Italy he gave birth, together with Silvestro Lega and Odoardo Borrani, to the “Pergentina School,” named after the Tuscan town where the group of artists went to devote themselves to en plen air painting. Late in life he returned again to Paris and came into contact with the Impressionists, becoming fascinated by their painting. He also continued to travel extensively, between England, Scotland and Naples, constantly searching for landscapes that could breathe new life into his art.

In 1883 he was approached by the Florence Academy of Fine Arts to teach, but Signorini flatly refused, continuing to the very end to want to break away from traditional dictates. Parallel to his artistic activity, Signorini also demonstrated a strong literary vein that accompanied him over the years; in fact, he also became an esteemed writer of essays. His most famous work is Caricaturisti e caricaturati del Caffè Michelangiolo, published in 1893. In addition, for about a year he had founded and edited “Il Gazzettino delle Arti e del disegno.” Despite a life dense with travels in Europe, Signorini never left Florence where he finally died on February 16, 1901.

The Macchiaioli, a group of artists formed in Florence in the second half of the 1850s, proposed a clear rejection of traditional art, based on the importance of drawing, in order to focus more on color. The group’s name derives precisely from the use of “spots,” or wide swathes of color with which the artists composed the image, juxtaposed with each other in smaller or larger sizes recreating the desired effects of light and shadow without the need to shade or resort to chiaroscuro. Underlying this theory was the idea that reality had to be reported on the canvas exactly as our eye perceives it, and indeed colors turn out to be the first thing our eye notices.

One of Signorini’s earliest known works dates back to 1859 and is entitled Il merciaio di La Spezia. It depicts a glimpse of the Ligurian city, thus imprinting on the canvas the travel experience the artist had had there. This is the first case in which the stain is applied to a painting not of a historical theme, but in an everyday scene: here, in fact, the arrival of the haberdasher in the main square is described, surrounded by women in typical costumes and festive children. A little later is the work Il quartiere degli israeliti a Venezia (1860), lost but of which a sketch remains; it turns out to be important along with the previous one in that both were much criticized, first because of the theme judged unworthy of being painted (in particular, Il quartiere degli israeliti depicts a degraded area of Venice) and second precisely because of the technique of the stain, which was considered incomprehensible by the public. At this stage, Signorini uses extensively the contrast between light and dark patches of color, which he combines rather sharply.

As early as 1861, softer and brighter juxtapositions of spots begin to make their way into his works, integrating light more into the composition. A key example of this resolution is Pascoli at Castiglioncello (1861). Signorini was very sensitive to social issues, which he presented in some of his later works to denounce injustice and injustice and provoke reflection in the public. The first work in this vein is the famous L’Alzaia (1864), a scene of vivid realism in which a group of laborers drags a barge along the Arno River in Florence(read more about the work here). Signorini succeeds in rendering all the fatigue performed by the laborers through various devices, for example, one notices the ropes pressing down on the shoulders of the subjects who are depicted hunched over, while some of them wipe off their sweat, letting one perceive the hard work they are doing. The feeling of fatigue is reinforced by additional details, such as the pants and sleeves of the rolled-up clothes, or the legs sinking into the ground. The message of denunciation is entrusted to the presence of two people portrayed in bourgeois clothes, a gentleman and a little girl (probably father and daughter) who go on their way completely ignoring the laborers, demonstrating how the bourgeoisie exploits workers who have to operate in conditions bordering on the inhuman in order to achieve their interests. Finally, the realism of the scene is entrusted to a color palette that ranges between blue, green and brown, or the colors of the earth.

Another important painting in terms of its subject matter is undoubtedly The Agitated Room in the Hospice of St. Boniface (1865). It was not very usual for painters of the time to deal with such a divisive theme as mental illness and asylums, and certainly this had never been depicted with such rawness devoid of sentimentality. In the painting we notice, on the left, the guests of the institution (the “agitated ones” of the title) who are all together in a bare room. One of them is railing against an unseen enemy, another is curled up under the table, yet another is wandering confusedly around the room. The color tones are all about white and brown, shifting from brightness at the top to gradual darkness as one approaches the group of figures, who seem more like shadows than people. By objectifying the situation and “photographing” it, Signorini intended to show that realities like this exist and are much closer than we think.

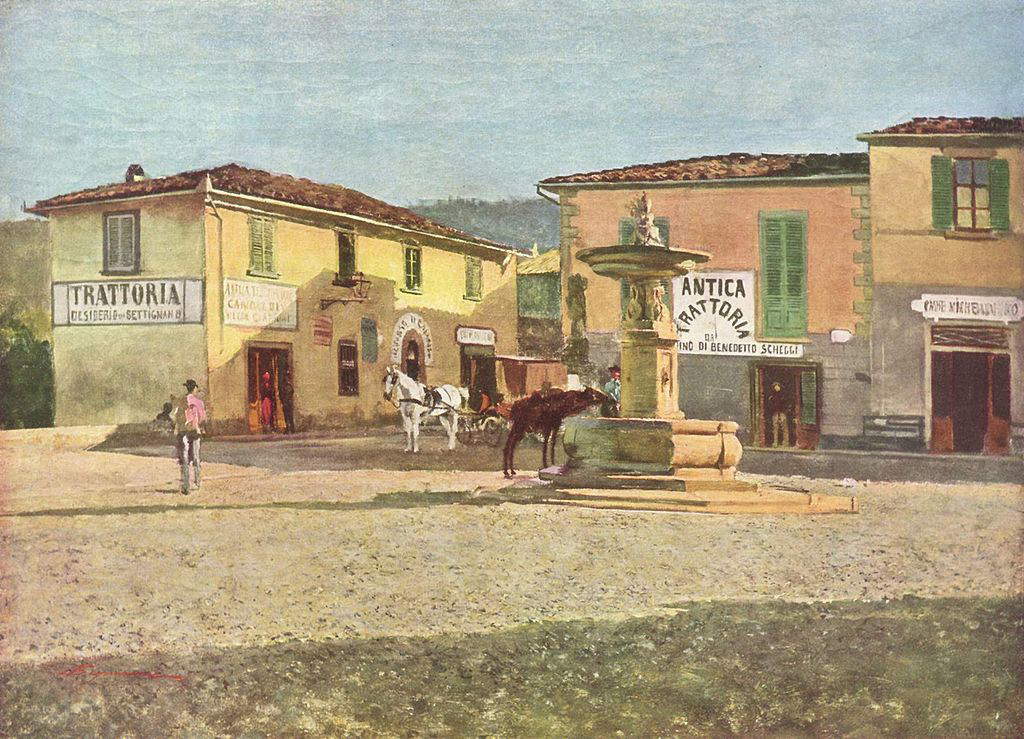

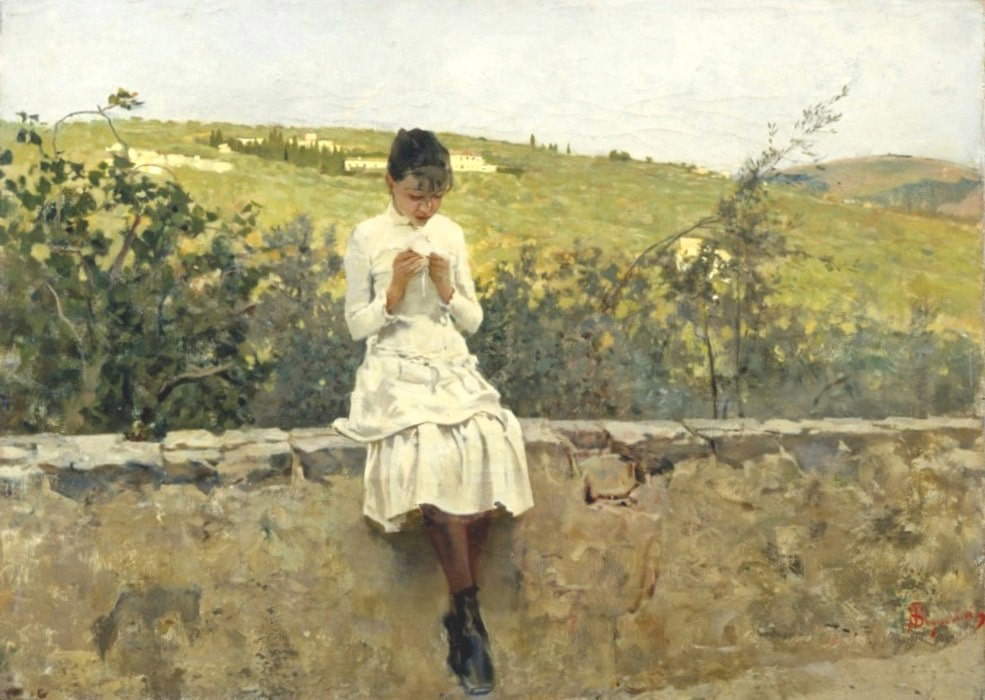

In the span of Signorini’s production, however, there is no shortage of landscape views that fit into his studies and experiments on open-air painting, including Via Torta, Florence (1870) Piazzetta di Settignano (1880) and Sulle colline a Settignano (1885), in which the scenes are decidedly serene and convey tranquility. Finally, the artist returns to the theme of the living conditions of the humblest in two other later works, Bagno penale a Portoferraio (1893-94) and La toeletta del mattino (1898). In the former, the conditions of a group of prisoners, visited by two officials, are shown. An uneasy feeling hovers in the painting, due to the stark difference between the ill-defined contours of the background and the more pronounced ones of the inmates. The second work is one of Signorini’s most complex, and features a very controversial subject for the time. Precisely because of the subject matter, Signorini never wanted to exhibit this work, but kept it in his studio, so it was discovered after his death. These two works, together with La sala delle agitate nell’ospizio di San Bonifacio, constitute to all intents and purposes a naturalist “triptych” that highlights the humblest and considered “lowest” roles in society.

Telemaco Signorini’s paintings are mostly found in Italy. He was a very prolific painter, and his works can be found in several collections. Among the museums that house significant nuclei of Signorini’s works is the Galleria d’Arte Moderna of Palazzo Pitti in Florence, where numerous works by the artist are encountered. Other paintings are kept at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, the Frugone Collections in Genoa, the Ca’ Pesaro Gallery of Modern Art in Venice, the Giovanni Fattori Civic Museum in Livorno, the Matteucci Institute in Viareggio, the Bano Foundation in Padua, and in the collection of the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze.

Several of Signorini’s works can also be found in antique stores and some masterpieces are kept in private collections. These include Il merciaio de La Spezia (1859), Il quartiere degli israeliti a Venezia (1860), Pascoli a Castiglioncello (1861)-which is in Montecatini Terme, L’Alzaia (1864), Sulle colline a Settignano (1885) and finally La toeletta del mattino (1898).

|

| Telemaco Signorini, life, works and style of the great Macchiaioli painter |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.