May is the month of roses par excellence. When the air becomes sweeter, roses bloom and gardens are dressed in enchanting fragrance. A noble, ancient and regal flower that for centuries has symbolized love, passion, devotion, grace and mystery, of all flowers, the rose is perhaps the most ambiguous and fascinating. Its petals are delicate to the touch, but the stem has thorns: it is the perfect image of human life, which alternates between sweetness and sorrow, passion and sacrifice. That is why the rose is not only botanical, not only ornamental, but also symbolic language. And right in the heart of May we celebrate St. Rita of Cascia, the “saint of the impossible,” the one who, according to tradition, received as a gift a rose that miraculously bloomed in the middle of winter, as a heavenly response to her unwavering faith. That rose of St. Rita is a powerful metaphor: the grace that blooms even in the deserts of the soul, the hope that can flourish where everything seems barren. And so, in this month that unites heaven and earth, body and spirit, art too bows before the rose, welcoming it on its canvases.

Painters of all times have looked to the rose not only for its beauty, but for what it evokes: love, death, spirituality, eros, femininity, eternity. The rose is revealed in all its forms: for art, like the rose, contemplates itself. Every painted rose is a poem that does not wither.

This is a journey through seven works in which the rose blooms...on canvas.

In the arms of the Virgin Mary, the Child Jesus receives a simple but omen-laden gift: a rose. Little Saint John tenderly hands it to her, but the symbolism is clear: it is a prelude to the passion, the sacrifice to come. Titian paints with warm brushstrokes, in a harmony that blends spirituality and humanity. The roses, like a bittersweet thought, link the mother’s purity to her son’s suffering.

The painting owes its name precisely to the affectionate gesture with which the little St. John offers roses to the Child Jesus, under the gentle, contemplative gaze of the Virgin. But this work, in addition to its artistic and symbolic value, is distinguished by a long history of traveling through Europe. In the 17th century it was part of the collection of Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Habsburg, who gathered in Brussels one of the most important art collections of the time. Later, the painting was transferred to Vienna with the rest of the collection, where it was reproduced in Theatrum Pictorium (1660), an illustrated catalog of the archduke’s Italian works. It was not until 1793 that the painting found its current home, arriving at the Uffizi thanks to an exchange of works between Emperor Francis II of Habsburg and his brother Ferdinand III of Tuscany.

Bosschaert, a master of Dutch floral painting, gives us a magnificent bouquet, immortalized with meticulous detail. Indeed, his still lifes are famous for their meticulous naturalistic precision: just look at the dewdrops on the petals or the insects resting on them. Yet the roses he paints, lush and opulent, seem too heavy for the delicate glass römer that supports them, as if beauty is about to overflow from its container. Among her most poetic innovations is her choice to place the bouquet in front of an open window-a simple detail that became her hallmark.

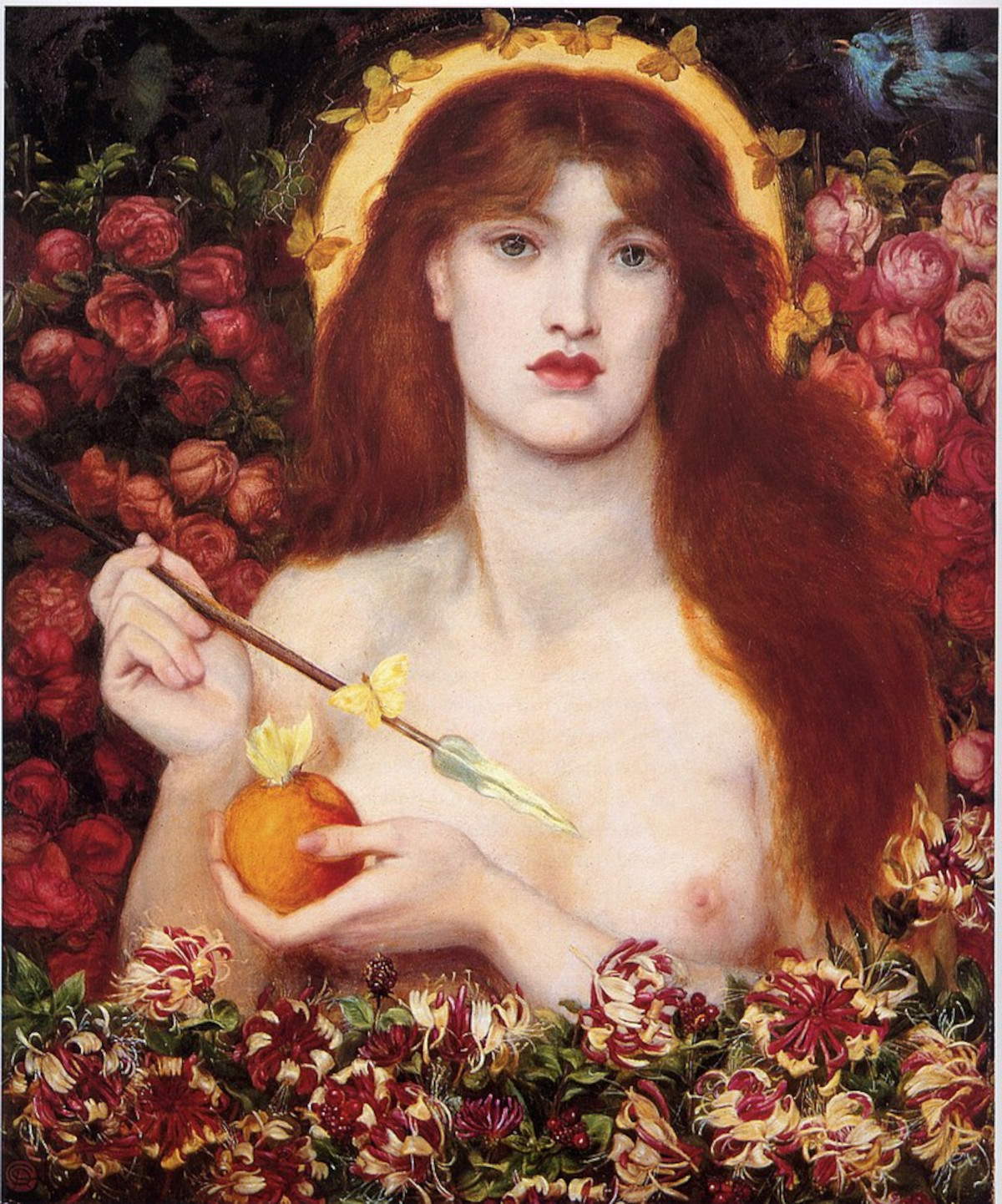

In this painting Dante Gabriel Rossetti molds a sensual Venus, with tawny hair and hypnotic gaze, clutching a golden apple and an arrow. He portrays the goddess of love in all her power: Venus appears as a half-naked young woman with a golden halo surrounding her head and long hair. She is immersed in a lush garden, where flowers envelop her body alluding, with the delicacy typical of the Victorian era, to feminine sensuality, mysterious and disturbing.

The golden apple she clutches in one hand is the famous apple of discord, the prize of the most beautiful of goddesses, with which she won the favor of Paris in the myth. In her other hand she holds a golden arrow - Cupid’s arrow, symbol of burning desire - pointing directly at her heart. On both objects, small yellow butterflies perch as light but symbolically dense presences: embodiments of the soul, of change, of the ephemeral. Around the halo, other butterflies dance in the air, reinforcing the impression that Venus is not just a mythological figure, but a vision suspended between the sacred and the carnal. The title of the work, Venus Verticordia, means “Venus who turns hearts” in Latin, evoking the goddess’s ability to change human feelings, to bend wills by the power of attraction alone.

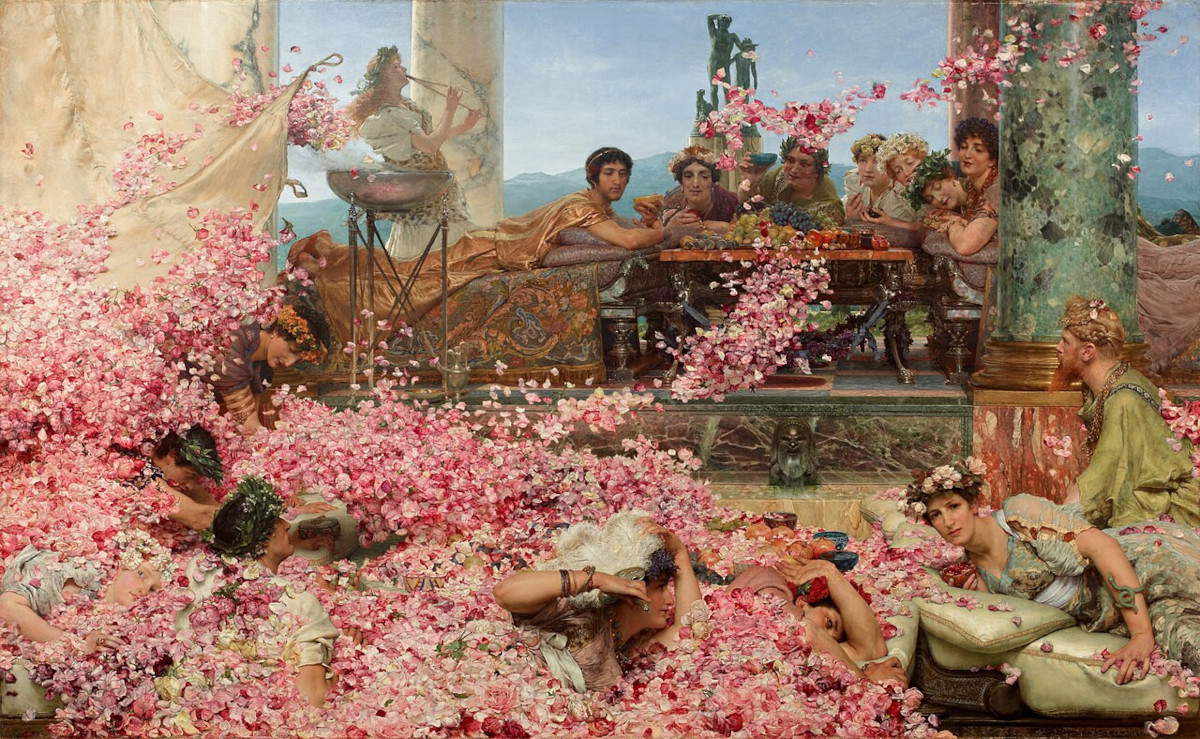

This opulent and disturbing painting takes us back to imperial Rome. As recounted in the Historia Augusta, Emperor Heliogabalus arranged a sumptuous banquet for his guests, concealing above them a false ceiling laden with rose petals. During the dinner, he had that deceptive vault opened, and an opulent rain of flowers swept over the diners: a gesture as spectacular as it was cruel, for some of them, suffocated by the petals, did not survive that breath of lethal beauty. Alma-Tadema paints each rose with obsessive richness, transforming it into a symbol of lethal luxury. The marble columns, purple drapes, and ecstatic, oblivious faces amplify the contrast between beauty and death.

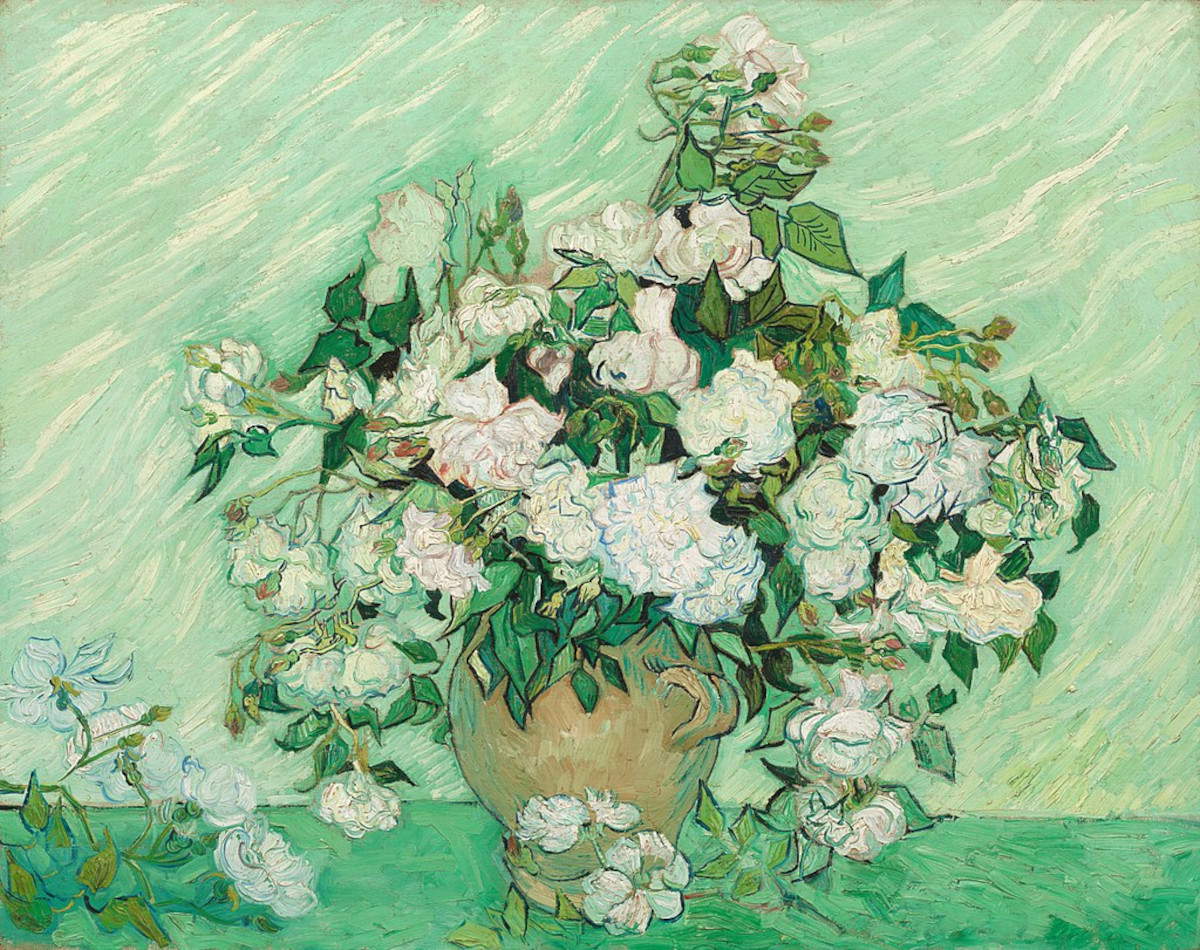

In the asylum of Saint-Rémy, at a time when Van Gogh’s soul was weary but not surrendered, this painting of fragile splendor was born. The vase filled with pink roses, set against a green background, is a hymn to hope and healing. Van Gogh painted this picture shortly before his discharge from the Saint-Rémy asylum. He felt he was coming to terms with his illness and with himself. In this healing process, painting was crucial. The painting is among his largest and most beautiful still lifes. The diagonal brushstrokes, moved by the wind of inner restlessness, seem to sway the flowers in the silence of the room.

In a hidden corner of a timeless garden, a woman places her face close to a rose in full bloom. The gesture is slight, suspended, almost sacred. Waterhouse, with her typical Pre-Raphaelite delicacy, captures the essence of the moment. The rose is soul and memory, and the woman who touches it seems to converse with a lost love, or perhaps with a life that could have been. All is silent except the silent language of the flowers.

John William Waterhouse knew how to infuse his female figures with a quiet, never shouted sensuality, made up of gestures. In The Soul of the Rose, the woman portrayed shows nothing explicitly sensual, yet the whole scene vibrates with contained desire. The way she approaches the rose, closing her eyes to catch its scent, one hand leaning against the wall, the other grazing the flower. It is an inner sensuality that manifests itself in the silent gesture of one who seeks in the essence of a flower the memory or echo of a feeling.

This Klimt canvas is a carpet of color. Preserved today in a private collection, The Rose Garden (Der Rosengarten) is fascinating for its intimate, almost secretive nature. Created by Gustav Klimt in 1912, the painting is not just a floral homage, but a glimpse into the artist’s private universe. The painter had a strong passion for roses: he found inspiration for this work in the garden of his house on Feldmühlgasse in the quiet suburban district of Unter Sankt Veit in Vienna’s Hietzing district. In that natural refuge, Klimt found a counterpoint to the mundanity of the city: there, amid the seasonal blossoms and the silence in the greenery, painting became meditation.

|

| The rose, symbolic flower of May. Here is how painters have depicted it in their works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.