Few artists like Ai Weiwei (Beijing, 1957) have devoted so much attention, so much perseverance, and so much of their output to the theme of the migrant and refugee crisis. Not only with works (stand out, among many others, Reframe, the installation with which in 2016 the Chinese artist covered the windows of the piano nobile of Palazzo Strozzi with the inflatable boats of migrants, The Law of the Journey, another installation presented in 2017 in Prague and composed of the silhouettes of 300 migrants, and again Safe Passage, the life jackets with which, again in 2017, he covered the columns of the Konzerthaus in Berlin), but also with films and books. Among the latter, the most recent is Humanity, first published in 2018 by Princeton University Press (under the title Humanity) and brought to Italy this year by Damocle Edizioni, an independent publishing house in Venice specializing in paperbacks and artist’s books.

Humanity is a collection of quotes by Ai Weiwei edited by Larry Warsh, a longtime collaborator of the artist: all excerpts focus on the theme of the refugee crisis. Or rather: on the “human crisis,” since the artist, on the occasion of the 2017 Prague exhibition, declared that there is no refugee crisis, but simply a human crisis, since many, in dealing with migrants, have lost their own core values. The quotes are taken from interviews Ai Weiwei gave mainly between 2015 and 2017, when the crisis, driven and fueled mainly by the atrocities of the civil war in Syria, was at its height. At the time (it was late 2015), the artist had also decided to visit theisland of Lesvos, one of the main outposts of the crisis as well as an important stop on the so-called Balkan route, for some time: over the years, the Greek island has seen tens of thousands of refugees passing through, mainly from Syria and Afghanistan.

|

| Ai Weiwei, Reframe (2016) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, The Law of Travel (2017) |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Safe Passage (2017) |

It is a flow that does not stop: from an article published in Internazionale in early August this year we learn that in thehotspot (i.e., the migrant identification center) of Moria, a small village not far from Mytilene (the island’s main city) about seven thousand migrants are currently being accommodated (compared to a much lower capacity of the camp: it should be three thousand people the maximum reception capacity). Or rather: they “live there,” says journalist Stefania Mascetti. Because the procedures for obtaining refugee status are often lengthy, and while waiting for an answer it is necessary to stay in thehotspot. As a result, migrants must equip themselves to spend weeks or months inside the camp. A kind of shantytown with tents and containers where people live in conditions at the limits of decency (indeed, often even below those limits). The Open Migration organization, which processes migration data, pointed out in its report on the case of the Lesvos migrants that the overcrowding of the reception centers “results in poor sanitary conditions and risk of disease,” and in particular “during the winter months the camp suffered from inadequate heating, with environmental conditions often below zero degrees and with accommodation often consisting of tents.” All of this results in a “very high risk to the health and lincolumità of the people hosted: according to the International Rescue Committee, 64 percent of those assisted suffer from depression and 29 percent have tried to take their own lives.”

The arrival situation in Greece has improved in recent years: the number of landings has drastically decreased since 2016. But in 2015, the year the war in Syria raged in its most horrific brutality, there were 856,723 landings in the country overlooking the Aegean Sea, according to data compiled byUNHCR, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. To give an idea of what the gravity of the situation was, consider that in the same year there were 153,842 landings in Italy, about one-fifth. In Greece today, the situation remains serious: in 2018 there were 32,494 arrivals (again, a comparison with the other two main countries bordering the Mediterranean is useful: in the same year there were 23,370 in Italy and 58,569 in Spain), and in 2019, as of August 18, there are 29,028 (compared to Spain’s 14,883 and Italy’s 4,393). However, conditions in reception centers are not improving: the Lesvos scenario is repeated in different parts of the world. And migrants are also often denied their dignity as human beings.

|

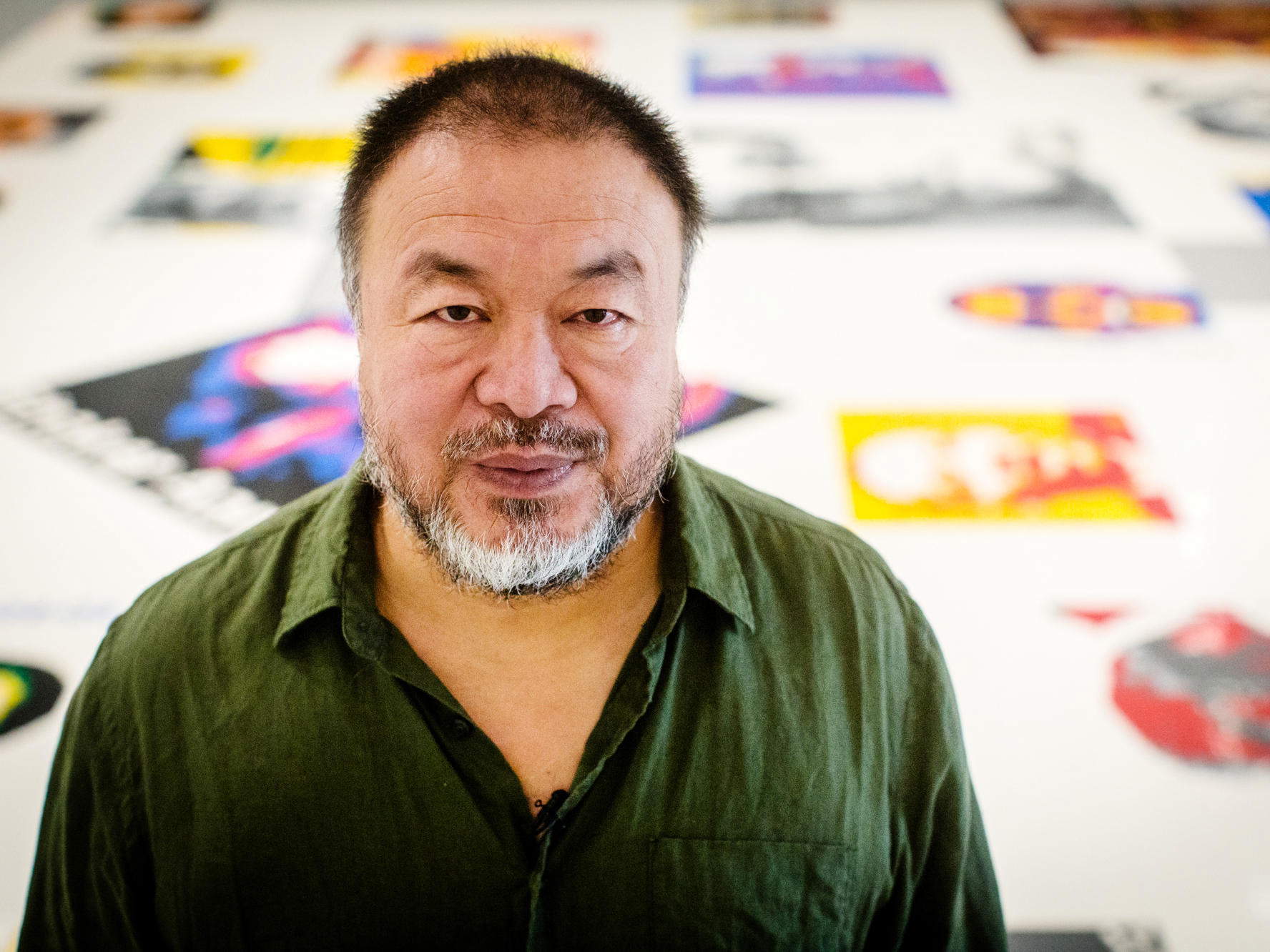

| Ai Weiwei. Ph. Credit Beck Harlan |

|

| Ai Weiwei, Humanity (2019; Damocles Editions). |

Aware of this situation, after his visit to the island of Lesbos, Ai Weiwei decided to bring to life the feature film Human Flow, a film, presented in 2017 at the 74th Venice Film Festival, dedicated to the global plight of refugees. Indeed, the artist wanted to remind us that there are not only the migrants closest to us, those crossing the Mediterranean Sea: all over the world there are people seeking refuge from wars and misery. And it is this conviction that led to the birth of Humanity. The quotations are divided into seven sections (“Humanity,” “Crisis,” “Boundaries,” “Power,” “Eradication,” “Freedom,” “Action”) and are excerpts from broader contexts (for each quotation, however, the reference is always present: moreover, these are almost all interviews also published online, so that the reader has the possibility of easily finding them in full, since the address is provided for each one). Nonetheless, they are animated by a force capable of ensuring that, on their own, they can strike and reach the reader. There is, of course, the risk that a book of quotations will lapse into liturgy: a danger apparently heightened by the format chosen for the book (a paperback, sleek and sparse, devoid of illustrations, except for a photo of Ai Weiwei in Lesbos in the opening and another image from his exhibition in Prague in the closing. However, this risk is mitigated (and perhaps even zeroed out) by the fact that Ai Weiwei does not try to convince the reader, but tries, if anything, to tell his point of view (as an artist who, moreover, has had to seek refuge abroad) and by trying to summarize an extremely complex topic in brief points, so that everyone can make up his own mind.

It is also deeply political, if for no other reason than the fact that Ai Weiwei chooses a direct language, which is not the journalistic language of data and numbers, it is not a snapshot of reality: it is, if anything, a narrative that aims at the reader’s capacity for empathy. As a connoisseur of mass communication techniques, Ai Weiwei proposes to the audience, with Humanity, a kind of barrier, a defense, a remedy against the storytelling of xenophobic and racist movements. But not to raise a useless wall against a wall: simply to bring us another voice and put us in a position to choose. Reminding us thatart is always deeply political.

Below are some quotes from Ai Weiwei’sHumanity :

“A refugee can be anyone. It could be you, or it could be me. The so-called refugee crisis is a human crisis.”

“I want to show the beauty of refugees. I want to show that even in the most difficult vicissitudes, beauty is still there. What is beautiful and what is dark exist in the same image.”

“As human beings, we are blessed with imagination. Our hearts can be big enough to allow us to imagine beyond the physical boundary. In this sense, human beings are so beautiful. That’s why we have poetry, we have music, we have art.”

“Human rights must always be defended, everywhere; and doing so benefits everyone.”

“Art concerns aesthetics, morality, our faith in humanity. Without this, art simply does not exist.”

“The hardest part is that you see that refugees desperately need to be understood. It’s not so much that they need money. They need people to look at them and see them as human beings.”

“In the saddest moments of our history, humanity has had to prove itself by proving itself to be humane to its own kind,” he says.

“I think we have lost our ability to feel compassion. Maybe it has something to do with our information age. Every day we see the misfortunes of refugees on the news, so we know what is happening. At the same time, the images dull us. We think the tribulation is so great that we cannot do anything about it.”

“As a human being, I believe that every crisis or tribulation that happens to another human being should be as if it happens to us.”

“Letting boundaries determine your thinking is incompatible with the modern era.”

“Today, the whole world is still in a struggle for freedom. In such a situation, only art can reveal the deep inner voice of each individual, regardless of political boundaries, rationality, race or religion.”

“I think we are lucky that information can flow and be transmitted through social media almost in real time. We can stand up against power.”

“In politics you certainly make a lot of sacrifices, but you still have to defend basic rights, otherwise it’s not worth being a politician.”

“For as long as human beings have existed, human beings have migrated. That is how we have become so intelligent, mixed, and more tolerant.”

“I don’t feel any anger at all. All my difficulties have made my life valuable. They have challenged me and made me see things differently. The people who put me in such difficult conditions were also acting as human beings.”

“It is never too late to do something.”

Ai Weiwei

Humanity

Damocles Editions, 2019

145 pages

10 euros

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.