There has been talk on more than one occasion on these pages about the increasing presence in exhibitions, biennials and art fairs of spectacular installations, of works that are immediately striking for their visual power but are often fragile or superficial from a conceptual point of view. Or of the spread in recent years of Instagrammable exhibitions, perfect for sharing on social media but lacking depth.

However, the fact that a work or installation is particularly photogenic does not automatically imply that it is devoid of meaning, nor does it imply that its value is exhausted in the aesthetic rendering of the image. A visually powerful work can at the same time be the bearer of complex themes, of reflections that go beyond the immediate impact, so to reduce it to a kind of mathematical equation, beautiful to photograph equals empty work, would be too simplistic and sometimes unfair. This is the case with the major monographic exhibition Chiharu Shiota: The Soul Trembles, now on view through June 28, 2026 at the MAO Museum of Oriental Art in Turin, curated by Mami Kataoka, director of the Mori Art Museum, a Tokyo-based museum institution that collaborated with the Turin museum to organize the show, and MAO director Davide Quadrio, together with Anna Musini and Francesca Filisetti. One cannot help but admit that The Soul Trembles is a very scenic exhibition (and here nothing wrong since the Japanese artist is also a set designer; a section is also dedicated to this aspect) and that it is precisely the monumental and spectacular installations that are the most photographed works of the entire exhibition: in fact, Chiharu Shiota ’s most celebrated installations come to occupy entire rooms of the Museum of Oriental Art, envelop the spaces in which they are placed and in turn envelop the visitors themselves who can literally walk through them; they are therefore extremely photogenic, Instagrammable and suitable for sharing on social media, but they carry deep, intimate and at the same time universal meanings. They speak essentially of connections: with others, with one’s own body, with the environment, with objects, with the cosmos. Woven and tangled threads of wool in deep red or raven black completely redesign the environments, creating immersive places of extraordinary power. But their visual power is never an end in itself. Through these weaves, the visitor is invited to reflect on the connections that run through our existence: on the relationships that unite us, on the subtle threads that link life to memory, on presence in absence, on the visible and the invisible. It is an invitation to recognize that every space and every body is crisscrossed by a silent web of relationships, a web that holds us together and that, just like the threads of wool, can tighten, loosen, tangle or open up to new forms of meaning. “Threads weave, tangle, break, knot, stretch. Sometimes, the threads that manipulate the heart can even become an expression of the relationships between people,” Chiharu Shiota explains, further emphasizing how the work can be considered complete when one is no longer able to follow the individual threads that compose it: “It is at that moment that I feel I can glimpse what lies beyond and touch the truth,” he says.

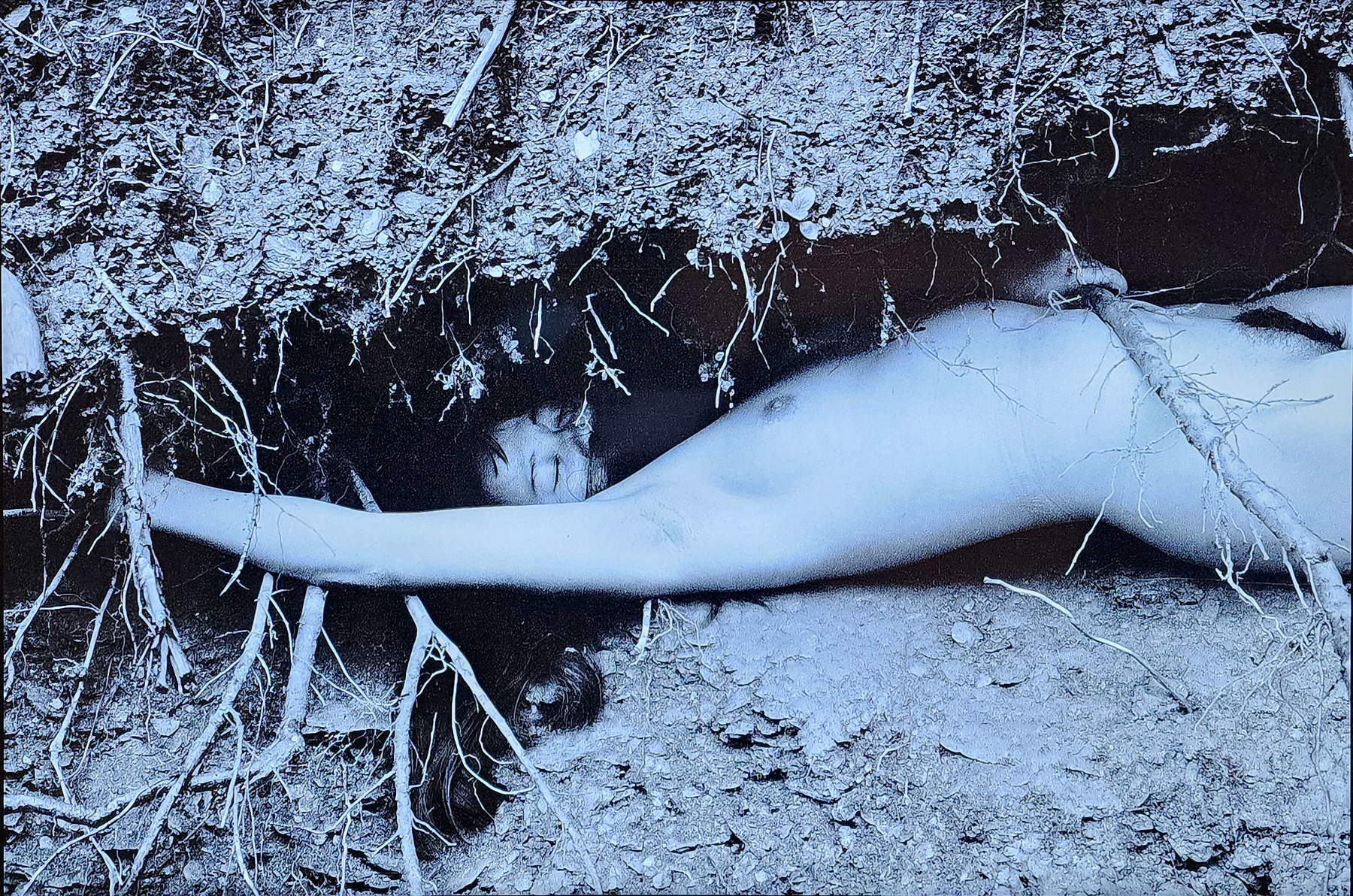

The large installation Uncertain Journey into which one is immersed as soon as one enters the Turin museum’s temporary exhibition spaces is an evocative example of these environmental installations where red woolen threads transform the exhibition space in extraordinary ways: bare frames of boats are arranged in the environment, spaced apart from each other, while deep red threads run through the parts of the boats intended for passengers and then rise to the ceiling, where they become large clusters of color, so dense as to be impenetrable to the eye. The entire room, pervaded by this dense web of red threads, then seems to suggest the idea of the many encounters, real or possible, that await at the end of this uncertain voyage, amplifying the feeling of suspension and uncertainty. Immediately afterwards one encounters Out of My Body, nets of suspended red threads accompanied by body parts scattered on the ground: a work that stems from a profound perception of the artist, namely that her soul was somehow being left behind, abandoned, while her body underwent treatment for the fight against the cancer that had struck her a second time. For Shiota, the act of using her body as a work of art is a way to give form to that absence, to imagine what is unseen and yet continues to exist in the void it leaves behind. “I lay out my body in scattered pieces and start talking to it in my mind,” the artist says. “Somehow I understand that this is the meaning of the act of connecting my body to the red threads.” And the drawings and sculptures in the same room express this very concept.

It is followed by In Silence, another visually powerful installation in which this time it is black woolen threads that intertwine and transform spaces. It is an installation that stems from a personal memory of the artist’s: “When I was nine years old,” reads an exhibition panel, “a fire broke out in the house next door to ours. The next day, there was a piano in front of the house. Burned until it was black as coal, it seemed to me an even more beautiful symbol than before. An indescribable silence descended upon me, and over the next few days, whenever the wind brought that burning smell into the house, I could hear my voice blur. There are things that sink into the recesses of the mind and others that, try as they might, find no form, physical or verbal. Yet they exist, like souls without a tangible form. the more you think about them, the more their sound fades from the mind, and the more concrete their existence becomes.” And In Silence evokes just such a memory, through a burned piano and equally burned chairs embedded in this weave of black Alcantara thread, which despite symbolizing silence is as if the whole plays visual music.

Instead, to be embedded within a tangle of black threads are white dresses in the work Reflection of Space and Time placed in the exhibition galleries of the permanent collection. In fact, a special feature of this exhibition is the placement of the works along the entire museum site, both in the temporary exhibition spaces and in those of the permanent collection; it is therefore an exhibition project that involves the entire MAO of Turin, creating one big immersion in Chiharu Shiota’s art. Returning to the work just mentioned, the clothes, like the skin covering the body, symbolize the boundary between an individual’s interiority and the external world. The idea evoked by the empty, unworn clothes is that of the feeling of presence in absence, thus of absence as a trace of being. And just before that, also on the permanent collection floor, one encounters Accumulation: Searching for the Destination, a monumental installation with hundreds of suitcases suspended by means of red wires descending from the ceiling. The suitcases evoke the concept of remembrance (the work was inspired by the discovery of old newspapers inside a suitcase found in Berlin, where the artist lives), but also the condition of migration of those people who leave their homeland in search of another destination. “When I look at a pile of suitcases, I only see a corresponding number of human lives,” the artist declares. “Why did these people take this journey? I think back to the feelings they had on the morning of their departure.” An installation, then, that suggests the journey of the refugee in search of a fixed abode and who takes with him all his baggage of memories, from the land he leaves behind to the one he hopes will welcome him. This is why in the same room three other suitcases, Where to go, what to exist - Cement and Where to go, what to exist - Photographs and Where to go, what to exist - Tube and Newspaper, are resting on the ground and open. The first filled with cement, the second with photographs, the third filled with cement, newspaper clippings, and a vinyl tube; all objects that suggest a lost past that is transported in the suitcases to a future where nothing is certain.

In addition to the large-scale installations discussed above, the exhibition traces chronologically through paintings, photographs and videos Chiharu Shiota’s production since the beginning to highlight and acquaint visitors with the themes and concepts the artist has expressed through the different mediums of painting, performance and installation. It starts from the beginnings, from a painting depicting a butterfly on a sunflower that she made when she was just five years old; then there is an abstract oil painting (after this she made no others) that she made in her first year at Kyoto Seika University, where she studied painting from 1992 to 1996, and for which she became frustrated that she prioritized color and technique without expressing any content. It was during the period of study in Australia undertaken during university, at the School of Art of the Australian National University in Canberra, that one night Shiota became a painting herself: she hung a canvas on the wall, then completely doused herself with red oil paint, including her face, and finally wrapped another canvas around her body. Photos of this 1994 “act of liberation,” as she called it, chronicle that performance. “It was the first work that was not a curated and finished work of art but rather an act of bodily expression in which I had put my whole being,” she explains, thus becoming part of the artwork.

There are also photographs documenting the first work in which the artist first used woollen threads, later to become a hallmark of her installations: the performance-installation From DNA to DNA, also from 1994, in which Shiota lay naked on the floor and wrapped herself in red threads that connected her to a large weave of the same that started from the ceiling of an interior room. To what extent does DNA transmission affect what happens in the mind of the person creating the artwork? This was the reflection that generated the work. There was, however, a period when he tried to use materials other than woolen threads, as shown in the installations Flow of Energy or Similarity with bamboo canes, Accumulation with acorns, One Line with bean pods, also beginning to reflect on theaffinity that exists between the order present in nature and that within the human body. This was a theme she returned to again in the 2000s, that of the connection with the earth and nature (symbols both post-mortem and of the origin of life), with several other performances, such as the one presented in Iceland during which she wrapped red threads around her own body, creating a situation of fusion between herself and the landscape. A few years earlier, in 1997, a workshop by performance art pioneer Marina Abramović that was held in a chateau in northern France also led her to lie down, completely naked, in a hollow dug in a sloping terrain, from which she had to attempt to climb out with no small amount of difficulty: the point of the performance was to evoke a sense of belonging to a country far removed from the one in which she lived and theinability to return to her country of origin. A 2010 video, Wall, which can be seen in the exhibition, again presents her naked crossed by “blood vessels” intertwined with her body to reflect on “the existence of human beings who cannot overcome the barriers” of ethnicity, nation, religion, but also family, where these barriers/boundaries are comparable to walls.

Thus, there are, as this exhibition continues to highlight, connections with one’s memories, between one’s soul and body, with nature, with one’s country of origin, but also with the objects we find in everyday life, as emphasized by the installation Connecting Small Memories where red threads truly connect everything, but especially with other individuals (the red thread of destiny that in East Asian belief unites people) and with the entire universe: on the occasion of the exhibition, the artist created a series of new drawings in which Shiota expresses the connection between human beings and the cosmos, as well as reflection on how small the former are in the face of the vastness of the universe and thus on the meaning of human existence. It is a deep reflection that has also sprung up in her in the face of the recurrence of cancer while preparing for The Soul Trembles exhibition project in 2019.

Finally, the last section is dedicated to theatrical set design projects: from 2003 to the present, Shiota has designed the sets for nine plays and theatrical productions; thus, it is considered an important chapter in the artist’s production. Among his set designs, one can also notice in the photographs on display plots of window frames, which refer to the installation Inside - Outside, a reflection between the intimate sphere and the outside world, visible in the exhibition in the corridor that leads to the beginning of the exhibition route.

After this long journey through the production of the contemporary Japanese artist who represented Japan at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, one can then understand how The Soul Trembles is not simply a spectacular exhibition, nor a triumph of images designed to circulate on social media. Rather, it is an experience that invites visitors to deeply question what holds us together: a reflection on the invisible thread that binds each individual to his or her own history, to others, and to the world he or she inhabits. Also coming to Italy after a long international tour from Tokyo to Paris, the exhibition project at the MAO in Turin, for the first time installed in an Asian art museum, demonstrates that what fascinates in these works and installations is not just the material that composes them, but what they manage to evoke and remind us that, like the threads that traverse and transform the museum’s environments, we too are intertwined with relationships and ties. Now we just have to wait for the monographic exhibition The Sense of Snow scheduled at MUDEC in Milan to immerse ourselves again in Chiharu Shiota’s artistic creation.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.