When in 1985 the Region of Tuscany dedicated an entire year to the promotion of Etruscan civilization, the project that developed took on a pioneering role in defining new ways of disseminating historical and archaeological heritage. TheYear of the Etruscans was not just an institutional operation: the initiatives promoted during the year, including the Florentine exhibition Civilization of the Etruscans, in fact contributed to renewing the gaze on an ancient culture whose complexity, fragmentary nature and fascination continue to exert a strong appeal even today. Over the years, the language of comics has also intercepted the same legacy, transforming the mythology and evidence of the Etruscan world into narrative tools capable of reaching different audiences. In particular, when illustrators and authors draw on archaeological heritage and historical sources, the result can become a space of discovery for a wide and transversal audience, even outside academic circles. We can give a small example. From a critical (or theoretical) perspective, the 2022 volume Comics and Archaeology, edited by Zena Kamash, Katy Soar, and Leen Van Broeck, explores the role of comics in transmitting knowledge of the past and influencing perceptions of society and politics. The book then analyzes the issues from an archaeological perspective, focusing on the representation and narrative use of material cultures.

At any rate, from artistic reinterpretation to thriller and from adventure to children’s popularization, all the works inspired by the Etruscan world show particularly heterogeneous approaches. The result is a vast corpus intended to highlight how Etruscan imagery, even today, represents a fertile resource for exposure. One of the earliest comic and civilization-related demonstrations dates back to 1955, when the Catholic weekly Il Vittorioso published the Rasena issue, illustrated by Gianni De Luca with texts by Renata Gelardini De Barba. The work is part of the periodical’s line of historical adventures and places the Etruscans in a narrative that merges diverse peoples, from the Phoenicians to the Romans. In a particular way, the link with the Etruscan world emerges from theillustration of a statue of a warrior (depicted by De Barba), inspired by an artifact then preserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In this regard, in 1961 Time magazine published an article in which it recounted that that sculpture, along with two other Etruscan figures, belonged to a series of fakes produced by the Riccardi brothers, artisans who specialized in the restoration of ancient ceramics. The deception, which lasted more than 30 years, became one of the most discussed cases in twentieth-century archaeology.

For decades the American public regarded a room in the Metropolitan Museum as one of the landmarks of Etruscan art, convinced that they were standing in front of three statues of warriors dating back some 2,300 years: a large head with helmet (nearly five feet high), and two full-height figures described as combatants ready for battle. However, the artifacts (previously lauded by various scholars as excellent examples of Etruscan sculpture) were suddenly disproved. The Met, for the first time in its history, was forced to admit that those works were fakes, the product of the skill of the Riccardi brothers, who were known for their work in the restoration industry with Italian antiquarians. The two brothers, initially dedicated to repairing fragments and small objects, soon found a market willing to accept ambitious copies. So in 1914 they decided to try their hand at three monumental figures. For the standing warrior they took as a reference the photograph of a small statue preserved in theAltes Museum in Berlin; for the monumental head they were inspired instead by a tiny terracotta head that, ironically, in 1961 already belonged to the Met; finally, for the second warrior they used the image of a figure depicted on an Etruscan sarcophagus purchased from the British Museum. They probably would have avoided using the sarcophagus if they had been aware that the British Museum, some two decades later, would have declared it a forgery and removed it from display. The indirect presence of the Etruscan warrior and the civilization itself inside Rasena therefore demonstrates how the comic strip, even without meaning to, intercepted crucial issues related to the circulation and authenticity of ancient works. This gives us back evidence of the complex relationship between popular popularization and art history.

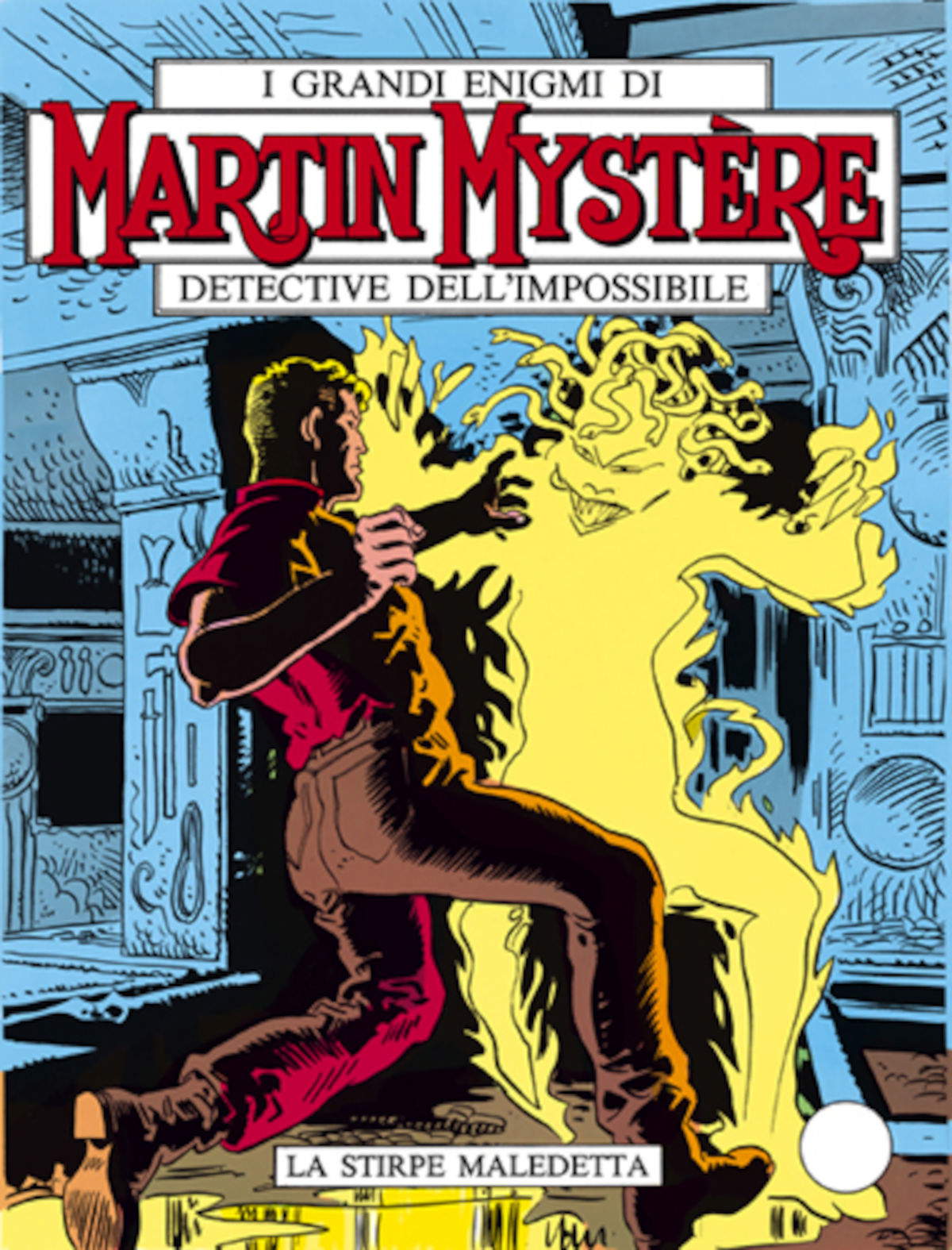

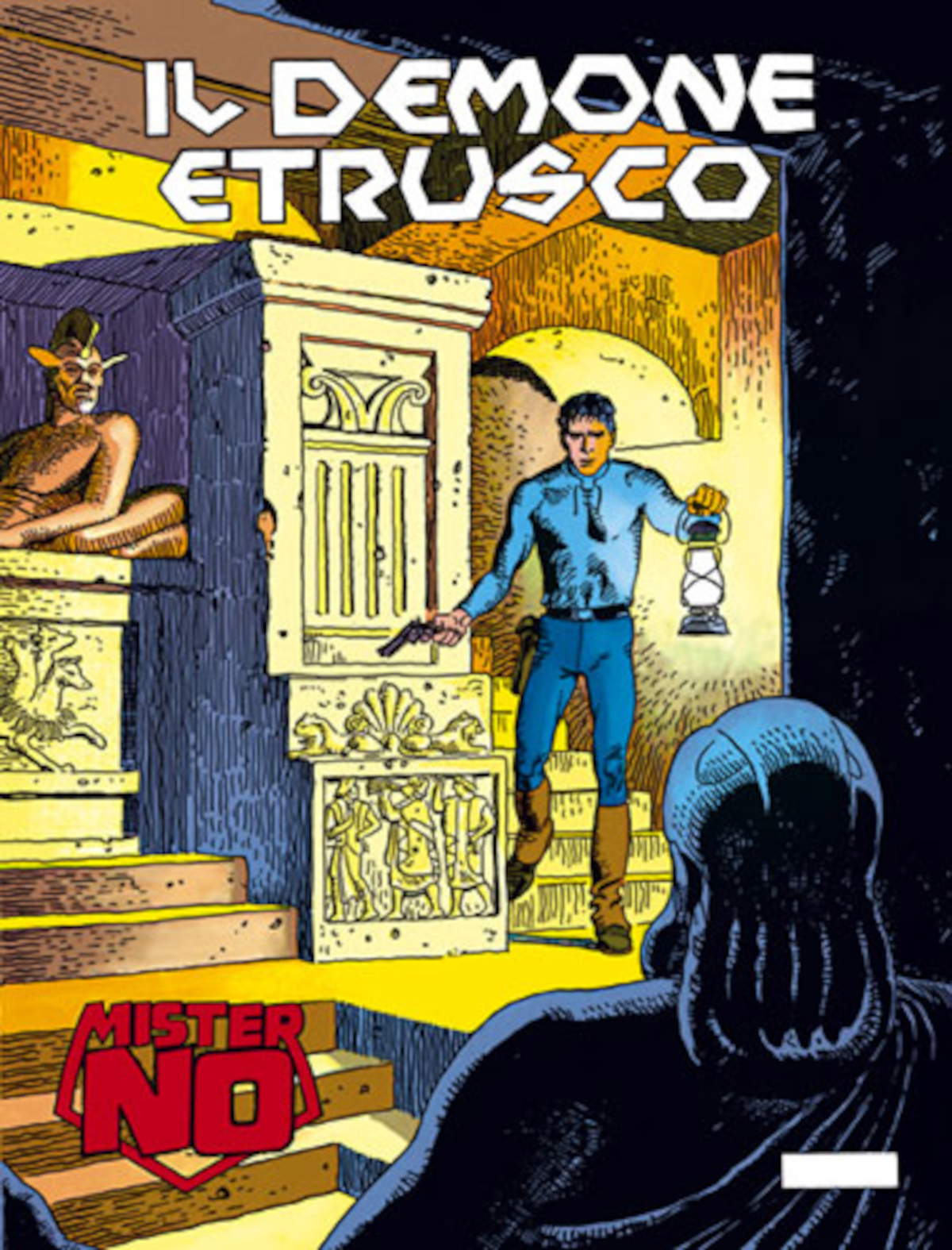

In 1970, the same civilization entered Bonelli Editore ’s adventure tradition with Mister No and the story Il demone etrusco (The Etruscan Demon), conceived and scripted by Guido Nolitta, with drawings and cover art by Roberto Diso. The reference to the Etruscans functions here as a catalyst for a bond based on murders, investigative tensions and archaeological excavations conducted illegally by American soldiers. The encounter with the contessina Claudia Sinisbaldi introduces an additional layer of drama, as archaeological heritage becomes the setting and trigger for conflicts related to the violation of artifacts and their illicit dissemination. Therefore, we can consider The Etruscan Demon as an example of how popular comics often use antiquity as a narrative device capable of amplifying mystery but especially the protection of artistic and cultural heritage. Another important juncture takes place between September 26, 1993 and May 15, 1994, when on the occasion of the exhibition Spina . Storia di una città tra i Greci e gli Etruschi at the Castello Estense in Ferrara, it was decided to reprint La stirpe maledetta, a story from the Martin Mystère collection originally published by Hazard and illustrated by Franco Bignotti. The updated edition, offered in the volume The Return of the Etruscan, is enriched by a dossier and an introduction in which Alfredo Castelli reflects on the narrative potential of the Etruscans. Enigmatic origins, religious cults difficult to reconstruct, the relationship with death and the apparent indecipherability of writing become elements capable of sustaining the continuous oscillation between scientific investigation and speculation. In this sense, the reprint was born as an attempt to reactivate an imaginary in conjunction with the 1993-1994 exhibition event.

Within the same serial, Bonelli placed the first version of La stirpe maledetta created with subject and script by Castelli and drawings by Bignotti and Angelo Maria Ricci. The setting between Tuscany, Lazio and in the wooded areas of Viterbo’s Macchia Grande, opens a story in which an assassin convinced he embodies the Etruscan deity Tarchies triggers a sequence of events involving Martin Mystère and Beverly Howard. References to Etruscan scripture and rituals maintain a constant tension between superstition, historical reconstruction, and pseudoscientific hypothesis, a balance typical of the character. It is 1994 and the Etruscan theme extends to other popular productions, such as Dick Drago 3. The Etruscan Mystery, published by Fenix. While adopting a different language than the Bonelli series, the choice to place the Etruscan element at the center of the link maintains a continuity in the widespread perception of a question-laden past.

The beginning of the 21st century marks a turning point, however, with Etruscan Journey. Six Frescoes in Comics, published by Black Velvet in 2009. The volume was the result of a creative residency involving authors Francesco Cattani, Marino Neri, Paolo Parisi, Michele Petrucci, Alessandro Rak and Claudio Stassi, who were invited to spend a week between Tarquinia and Cerveteri, with visits to the Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia and the main archaeological sites in the area. The goal of the comics seems to be a direct contact with atmospheres and impressions of the places, transformed into short stories that return fragments and narrative possibilities, while the graphic interpretations highlight how the absence of exhaustive documentation can become imagination and creative stimulus. Consequently, all of this leaves comics to complement the languages of popularization without binding themselves to its models. Alongside the Italian and European productions, an important role is played by the Disneyuniverse. Uncle Scrooge and the Enigma of the Etruscan Bride applies the codes of the Disney adventure to an archaeological context in which historical finds and hypotheses generate comic and investigative dynamics, while maintaining a recognizable and accessible narrative structure. Mickey the Etruscan - Ancient Civilizations: from the Sumerians to the Etruscans, published in the series dedicated to ancient civilizations, instead entrusts Mickey and Goofy with a journey through time thanks to the time machine. The story presents simplified but correct explanations of the Etruscans and the ancient cultures covered, integrating popularization and adventurous pace.

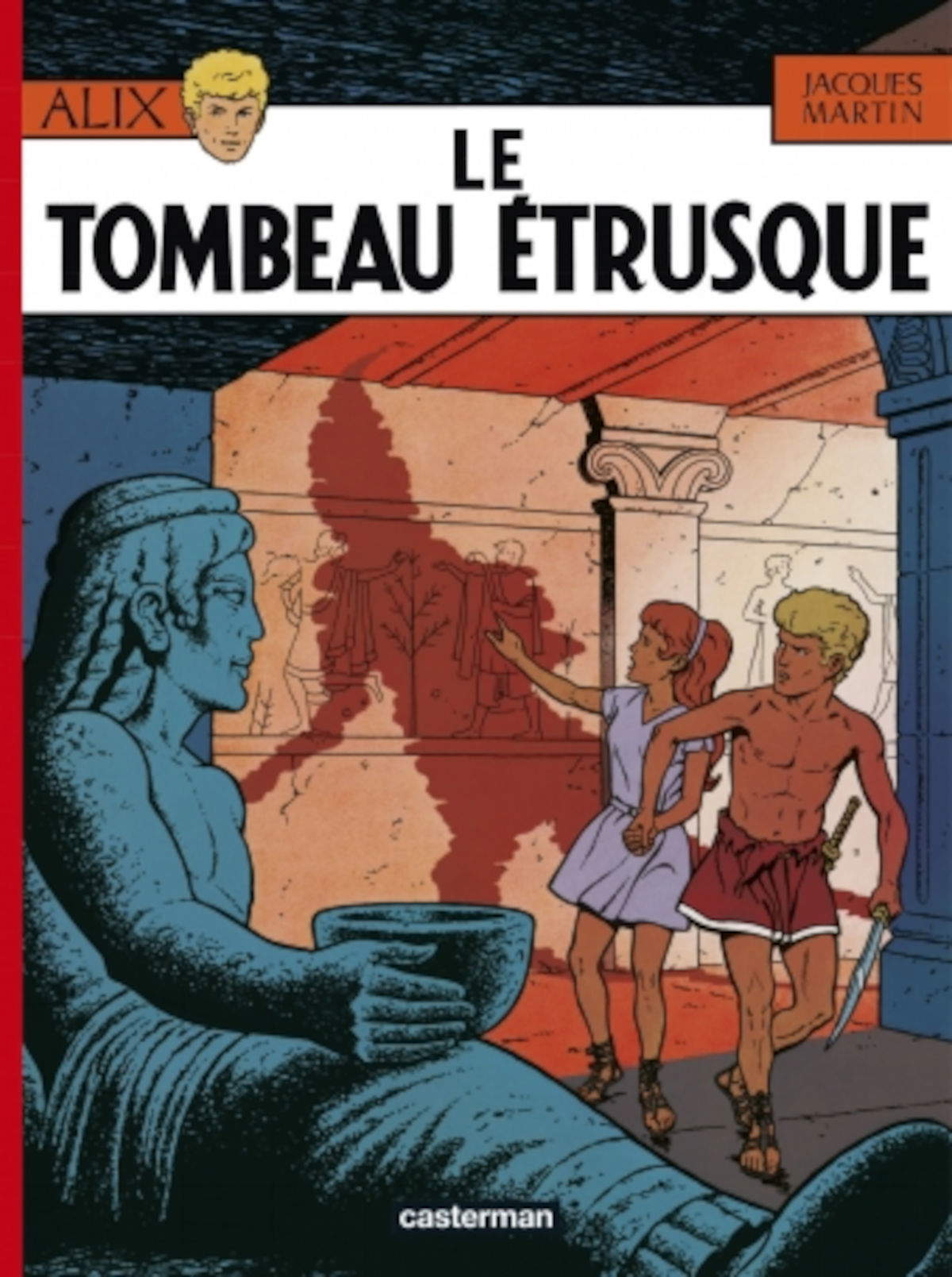

A parallel contribution then comes from the Francophone tradition with Alix - Le Tombeau étrusque by Jacques Martin published by Castelman. In this case the Etruscan reference intervenes in a Roman context through a fusion that opens with a nighttime attack on a large agricultural estate. Alix, Enak and Octavius, Julius Caesar’s nephew, rescue a child destined for sacrifice to the god Baal-Moloch. The episode introduces a secret society attempting to restore an Eastern cult, with Brutus and Tarquini’s prefect involved in political and religious dynamics. The Etruscan element surfaces mainly in the settings, such as the archaeological area of Tarquinia (present in almost every comic book), and in the cultural framework that supports the narrative development, integrating historical references with the adventurous codes typical of the series.

In all the works, Etruscan imagery therefore manifests itself as a field of experimentation, between what is known and what cannot be defined with certainty. Comics thus become a tool capable of approaching a fragmentary heritage, now emphasizing mystery, now reinterpreting history, and now proposing new perspectives of art. The archaeological sites of Latium and Tuscany themselves, such as Cerveteri, Tarquinia, and the settlements of Vulci and Chiusi, are transformed and become indispensable tools for understanding the civilization and communicative language of comics, providing comics with an indispensable heritage for knowing and reinterpreting the same culture. Their presence undoubtedly lends authority and depth to narratives, and this allows for the combination of fantasy and knowledge. Places and temporal distance thus constitute a different narrative possibility. In this sense, Etruscan civilization continues to emerge as a territory in which authors and illustrators project questions rather than answers and confirm the vitality of a confrontation between archaeology and imagination that, even today, has not exhausted its potential.

The author of this article: Noemi Capoccia

Originaria di Lecce, classe 1995, ha conseguito la laurea presso l'Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara nel 2021. Le sue passioni sono l'arte antica e l'archeologia. Dal 2024 lavora in Finestre sull'Arte.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.