The history of Italian pointillism passes through Genoa. Pass through Genoa the social unrest that would later spill over into the arts. Passing through Genoa were the first Symbolist hotbeds that animated Italian painting in the latter part of the 19th century. And at the center was always Plinio Nomellini, who arrived in Liguria in the spring in 1890 and left twelve years later for Versilia. He had arrived in Genoa perhaps with the idea of staying there for a short time (we know this from a letter from him), for reasons of circumstance: the XXVIII exhibition of the Promotrice, the chance to study a different landscape than that of his Tuscany, and in all probability also the suggestions of one of his masters, Telemaco Signorini, a regular visitor to the Ligurian coast, Riviera di Levante, Cinque Terre area, Riomaggiore. And then, driven by an eagerness to “try new things,” not only intending to stay for a long time, but determined to call many of his Tuscan friends here, so much so that the following year we have to imagine him strolling along the cliffs together with Giorgio Kienerk and Angelo Torchi to attempt the first pointillist experiments where the water of the Ligurian Sea meets the steep contours of the sheer cliffs, amidst the swells, among the caruggi of the coastal villages. “Having happened by chance to be in Genoa,” Vittorio Pica would write in Emporium when Nomellini was at the height of his career, “he had settled there, taken by the magnificent beauty of that city, [...] forced, in order to make ends meet at the worst and to be able to bear the expenses for the canvases, colors and frames of his new paintings, to make during several hours of the day and for even derisory prices the portraits of the English, French or Norwegian sailors who were passing through the port, with their merchant ships, of whom sometimes, when they were satisfied with the ’skill of his in capturing the likeness of their rude physiognomies, they would give him the commission to reproduce the appearance in watercolor or pastel on a card, adding a few more liras to the established fee for his own portrait.”

This alleged activity as an indefatigable port portraitist is lost in legend: what is certain, is that from the very beginning Nomellini was caught up in certain of his “flamboyant art projects” that would cost him toil, hardships, tribulations and even, as will be seen, jail time. The exhibition that Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellini is dedicating to the Nomellini of the Genoa years(Plinio Nomellini a Genova, tra modernità e simbolismo), the first monographic exhibition on him after the one in Seravezza in 2017 and the first ever entirely dedicated to this period of his career, has set itself the goal of investigating them all, one by one, the flamboyant projects of the Leghorn painter. And the two curators, Agnese Marengo and Maurizio Romanengo, together with the large scientific committee, looked at this phase of Nomellini’s production as one would look at a cell under a microscope, and it emerged that Genoa was a crucial moment. Decisive. Not only for Nomellini, but for so much Italian culture at the turn of the century. That city that had initially attracted the artist because of the light and the sea had become a kind of processing center for the new, for all the new. And apparently there is still so much to be said about Nomellini, about the Genoese Nomellini: about his early trips to the coast together with Torchi, with Kienerk, with Ermenegildo Bois, that is, about that “school of Albaro” to which the paternity of pointillism is to be attributed. On his friendship with Pellizza da Volpedo. On Nomellini’s early successes. On the fertile association with Edoardo de Albertis. On the Sturla cenacle that gathered in the city’s trattorias so many of the finest minds of the time and that would become a flame to fuel the embers of Italian symbolism. On his idea of art as a terrain for social claims.

And indeed the exhibition (no more than about fifty works, most of them from private collections and commercial galleries) rings in discovery after discovery of unpublished documents, all presented in Maria Flora Giubilei’s essay published in the catalog. The merits of this exhibition, however, go beyond Nomellini’s biography, which was already pretty well established: the visitor who decides to follow Marengo and Romanengo’s itinerary carefully will derive the impression that it is an exhibition about Genoa more than about Nomellini. And on Genoa as a glittering, nervous agglomeration of a new modernity that saw in the painter who arrived from Livorno something more than his aedo. Nomellini, one might say after seeing this exhibition, was an inventor. Of course: we already knew that; we did not need another exhibition to reiterate the importance of his production. And his drive did not end with Genoa, because with the move to Versilia would come the more mysterious, more lyrical, more D’Annunzio-like season of his art: after Liguria, Nomellini still had so much to say. Yet so many addresses of Italian culture at that time transited through the fervid Genoese experience.

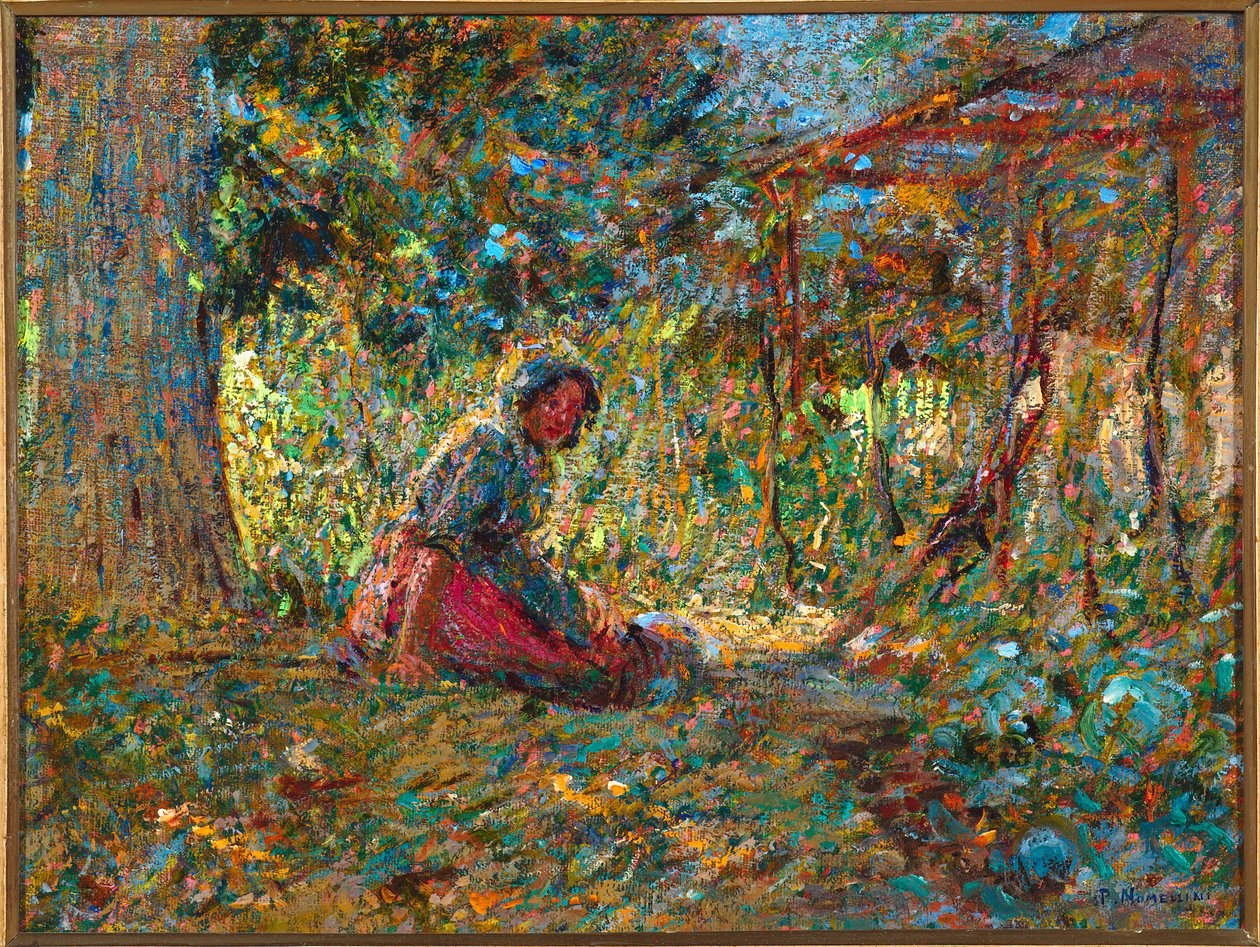

Nomellini, for his part, in order to open up to the new, had had to commit a “betrayal,” as Nadia Marchioni had written at the time of the exhibition eight years ago, with respect to the teaching of his master, Giovanni Fattori: he abandoned the Macchiaioli-style naturalism of his first phase (an example of this can be seen in the painting Al parco (In the Park), 1888, which is directly compared with a Strada di paese (Street in the Village) by Giovanni Fattori: it is these two paintings, together with a Memoir of Genoa , however, placed out of context on the entrance wall, that opens the exhibition), and having abandoned the Florence where he had learned to paint and where, on the tables of the trattoria Volturno, he had made all the friends he would later bring to Genoa, Nomellini would decide to move to Liguria to devote himself to the study of the sea, to the study of that “continuous movement of the [...] shores and the port” which, he would confess in a letter to Telemaco Signorini as soon as he arrived in the city, had made a good impression on him and offered him the spur to try those “new things” he was seeking. Before that “betrayal,” of course, a phase of experimentation, of transition, had become necessary: that Ricordo di Genova, for example, while already presenting that touch painting that was at the center of his research, still retains the memory of theFactorian setting in the two figures that appear seated on the shoreline, and before that the Fienaiolo of 1888, the youthful masterpiece, explicitly traces a Boscaiola by the master (so much so that the two works are now exhibited side by side in the major exhibition on Fattori at Villa Mimbelli in Livorno curated by Vincenzo Farinella). Nomellini’s researches were nourished by his proximity to the sea, and the first room of the exhibition grants the visitor the chance to walk among the rocks and carrugi along with the painter and his companions who, like him, spent their days painting on the Genoese coast.

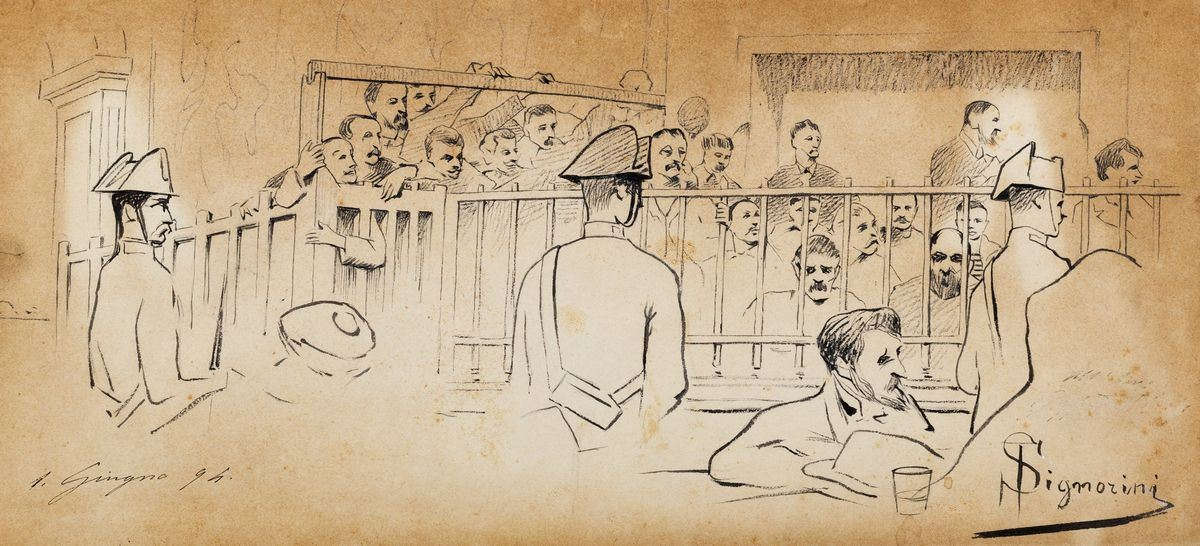

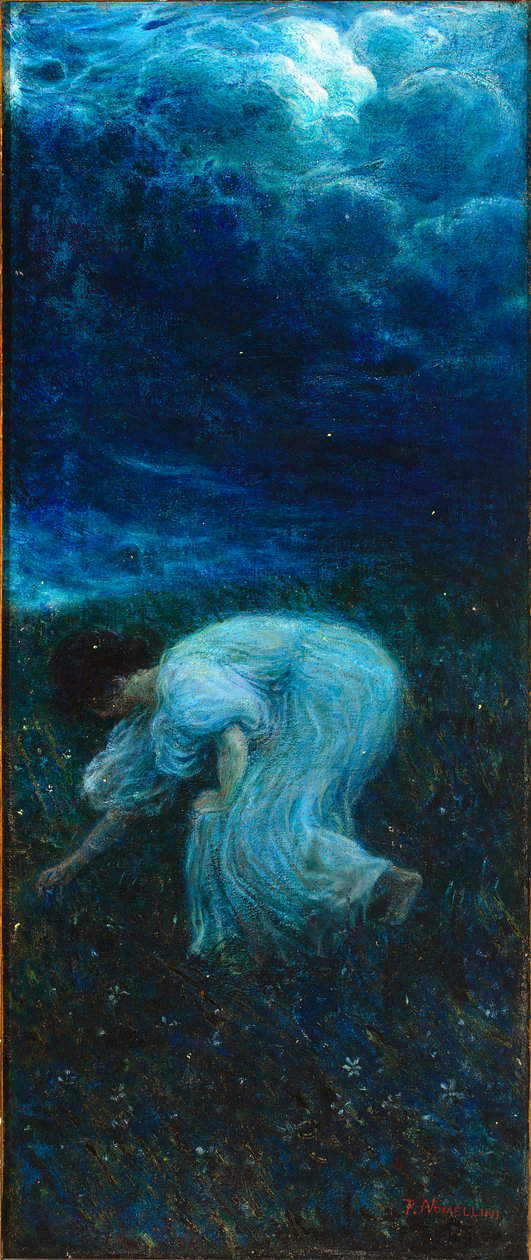

What moved Nomellini, Kienerk, Torchi and even Pellizza (who was also in Genoa in 1890: of strong impact, in the second room, is the comparison of their respective seascapes, painted together, at the same point on the coast) is their interest in French painting: first towards the Impressionists, and immediately afterwards towards the pointillists, towards those “very humble servants of Pisarò, Manet, etc. and ultimately of Mr. Müller,” as Fattori had contemptuously called them, who had nonetheless succeeded in achieving a new light through the division of color, juxtaposing touches of pure pigment, working on complementary tones, and offering the Italian Divisionists the cue for new, feverish, warm interpretations: Nomellini then “experimented,” the two curators write, “with the division of color while constantly seeking spatial depth, rendered with the impetuosity of foreshortened walls, atmospheric thickness and movement of figures.” This can be clearly seen in certain works from 1891 that mark the definitive break from the master’s teaching: thus we are talking about the Ricordo di Milano, where the brushstroke in touches serves to evoke the fleeting tones of memory, or experiments such as Nell’orto where the whole garden loses its consistency and becomes light and color. Even Telemaco Signorini, at this stage of his career, sensitive as he was to the suggestions arriving from France, had tried to offer to the relative the flickers of light that rest on the leaves, on the ripples of the sea, on the dry stone walls: one of his late masterpieces, Ligurian Vegetation at Riomaggiore, is exhibited near the works of Nomellini and close to a painting by Angelo Torchi, Dalla finestra, which adopts an entirely similar composition. One of the most mature and fascinating outcomes of this phase of Nomellini’s painting is the Naufragio, a painting where burrs of white serve to render the effect of sea foam, where the blowing of the wind is rendered only by the rhythm and thecourse of the brushstrokes, and where we can already sense some flashes of that “social reflection,” as the next section of the exhibition is titled, that would explode a few months later in a number of paintings all aimed at evoking the condition of factory workers in Genoa. The next chapter of the exhibition is all built around one of Nomellini’s best-known works, La diana del lavoro, illuminated with extraordinary effectiveness, with the lights able to bring out, and it is not easy, the three-dimensionality of a painting that makes the two figures in the foreground leap off the surface: merit of the exhibition, however, is not so much that of having arranged the painting in the most suitable lighting conditions to capture every brushstroke, every passage of light, every glow that rests on the skin and hat of the worker who looks ahead waiting for the signal, the diana, to begin the day of toil. Nor is it to insist on the continuity of Nomellini’s interest in workers’ ambitions: the work devoted to shipyard workers is compared with a painting from his Tuscan years, a group of peasants returning from work. No: the main merit is to have exhibited La diana del lavoro along with a group of testimonies about the trial that Nomellini, accused of participating in the subversive activities of an unspecified group of Tuscan anarchists, was forced to face in 1894, rare material to see in an exhibition: there are engravings that give an account of the miserable conditions of the Sant’Andrea prison where Nomellini was imprisoned for a few months, there is the portrait of the poet Ceccardo Roccatagliata Ceccardi who, like Nomellini, was moved by the same ideas of social justice, there is the drawing of the trial performed by Telemaco Signorini that would later be decisive in getting his young colleague cleared of all charges, since his moving testimony, coupled with the untiring work of lawyer Giovanni Rosadi who set up a defense line based on the painter’s total extraneousness to any sedition vague, probably succeeded in orienting the jury that eventually granted Nomellini a full acquittal (Signorini’s memoir concluded thus: “One task I have had, and that is to address a prayer, on behalf of the Academy of Florence, to the Tribunal, that it may wish to restore to art one of the finest intelligences, one of the most fruitful workers, a young man who is destined for a shining future, and who, besides doing honor to himself, will do so to his country. For my part, and that of my colleagues, I add only this: we are old and we retire; let the Tribunal see to it that the young men who are to succeed us in the way of art are not throttled by prison bars.”)

The harshness of the imprisonment, however, suggested greater circumspection to Nomellini, so much so that his production, from that summer of 1894 onward, would almost entirely abandon the strand of social denunciation, which would nevertheless resurface karstically even several years later (the lithograph for the magazine Il lavoro, from 1903, is the brightest example), and would open up to the symbolism that had matured in the circles of the Sturla cenacle, the sodality of artists, writers, and poets who had gathered around the journalist Ernesto Arbocò and around his dinner table (when he could host everyone at his home: later, the reference would become the Trattoria dei Mille in Sturla) discussed art, politics, poetry, and letters. They even went so far as to imagine their own imaginary “Trattoria del Falcone” and to design a decorative cycle, intended for the walls of Palazzo Spinola Gambaro in Via Garibaldi where this group of artists had managed to obtain a fund, and of which traces were sought in vain during the preparations for the exhibition at Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellini. The exhibition itinerary then seeks to highlight the contribution of Arbocò and the cenacle of Sturla to Italian Symbolism, finding it in the elaboration of a landscape, and particularly of a nocturnal landscape, full of allusions, ideas, mystery, and other meanings. Night is Ceccardo Roccatagliata Ceccardi’s “city of the unknown,” the “port disclosed on the abyss of the ether,” a familiar and distressing presence that permeates the city when the sun goes down. This was the time when the whole of Europe knew the poetics of the landscape-state of mind, and evidently not even Genoa was immune to what was being worked out across the continent behind the formulations of Amiel’s Journal Intime : parading through the exhibition are paintings by artists such as Federico Maragliano, Giuseppe Mazzei and Edoardo De Albertis where the night of Genoa is cold and enveloping, recognizable and elusive, enigmatic and gloomy, empty and full, gray as the smoke of its smokestacks, occasionally brightened by a light that becomes almost a hope. These are nights swollen with life and dark nights of silence: Maragliano is present with a swarming Evening in a Genoa street and with a Nocturne where a moonlight soothes a creuza that penetrates the vegetation, and Nomellini lingers on two “ciccaioli,” the street sweepers who cleaned the streets of downtown Genoa by the minute at night, and transcends reality with Le lucciole (Fireflies), a work exhibited alongside Edoardo De Albertis’sAutunno(Autumn) to evoke a diptych,Autunno latino (Latin Autumn), which enclosed the Genoese sculptor’s marble and a mystical landscape by Nomellini, of the same mysticism that pervades the painting exhibited at Palazzo Nicolosio Lomellini. “One had to push oneself to stop in matter the incorporeal semblance of the dream.” this was the intent that moved Nomellini to deepen his friendship with De Albertis after seeing, as Giacomo Goslino well reconstructs in the catalog, one of his works, Elevation, at the 1895 Turin International Exhibition, and it was this vision that suggested to him that it was the case not only to praise in print that slightly younger colleague of his, but to try to work with him. In the paintings that spring up alongside De Albertis’s sculptures, wrote a scholar like Gianfranco Bruno in the 1980s, "Von Stuck’s somber imagination appears dissolved in a spiritual lyricism, and the refined linear ductus , of Klimtian descent, is converted into a phantasmagoria of landscape." It is Genoa that sees in nuce, and then already perfectly accomplished, the more lyrical Nomellini, the one from the season of Versilia and Torre del Lago, the one close to theAlcyone of D’Annunzio, the one of the fiery pine forests, of the nymphs erupting from the barks of the trees (his wonderful Ninfa rossa, a masterpiece of this new Tuscan phase, is displayed in the exhibition next to the Lucciole to suggest this continuity). It was in Genoa that that Symbolist turning point took place, wrote Giuliano Matteucci on the occasion of Nomellini’s exhibition held at the Palazzo della Permanente in Milan in 1985, “which would increasingly distance him from the strictly Divisionist research, assuming that he ever intended Divisionism to be more than an innovative technique, useful for enhancing the communicative effectiveness of an image to which he already in these years entrusted an eminently social value or a profound ideal and poetic meaning.”

After a lunge on Nomellini’s graphic art (there is the lithograph for Lavoro, there is the famous advertisement for Sasso oil, there is the even more famous Inno all’olivo that the artist drew on paper in 1901 to illustrate Giovanni Pascoli’s poem of the same name: this is a Nomellini no less experimental than the Nomellini of the paintings, a Nomellini who in his own way, as Veronica Bassini notes in the catalog, marks the history of the poster by virtue of the originality of his formal solutions, the strength of his personality and the communicative effectiveness of his images), the leave-taking is entrusted to some landscape paintings from the early Versilia season: a little over thirty-five years old and at the end of his Ligurian experience, Nomellini was a completely different artist than the one who had arrived in Genoa, a Nomellini who had definitively abandoned the still nineteenth-century research linked to the development of the Impressionist legacy and entered the new century with a painting overflowing with poetry. The Versilia of sunsets, of woods and pine forests, the shores of Lake Massaciuccoli, and skies laden with brackish become the subjects of paintings in which the landscape of the northern Tuscan coast is transfigured into poetry, into vision.

It should be noted that part of Nomellini’s “Symbolist turn,” as Matteucci had called it, would perhaps not have been possible without the experience of La Riviera Ligure, that magazine that had started as a newsletter of the Sasso and that, properly financed, supported and promoted by thecompany, would have become a sum of the best artistic and literary intelligences of the time, since Pascoli, Campana, Gozzano, Govoni, Moretti, Pirandello, Ungaretti, Capuana, Rebora, Saba, the same Arbocò and Roccatagliata Ceccardi, and it would be illustrated by Nomellini, De Pisis, Kienerk, De Albertis, Carena and so many others brought together by the luminous editorship of Mario Novaro, who had turned it into a kind of periodical catalog of the Ligurian olive oil mill (which at most offered, in its first issues, alongside product sheets and price lists, a few recipes to make with oil and a few articles on the Ligurian landscape: despite the simplicity of the publication, the company must be credited with having matured from the outset the intuition of wanting to produce a groundbreaking publication of the territory for those times) in a magazine that, while never losing its promotional character, had risen to the top of national literary production. In front of these pages, and on top of these pages, Nomellini had the opportunity to learn, to confront himself, to elaborate ideas, novelties, suggestions, to tune his art to the rhythms of the poetry of Pascoli, of Roccatagliata Cccardi, of others who animated La Riviera Ligure , transforming it into a voice of the most up-to-date tips of the artistic-literary vision of those years. In the exhibition, the role of the magazine is hinted at in the brief passage on graphics.

One comes to think, seeing the outcomes of that sojourn that began and ended among the cliffs of the Ligurian coast, first examined with the eye of the scientist attentive to the mingling of colors and the breaking of light on the cliffs and then with the soul of the pagan priest transfiguring those same beaches, those same coves, that same expanse of water into mystical vision, that for Nomellini there was probably no difference at all between art and poetry. “After the long experiments in the practices of art,” he would write in one of his biographical notes, “when I venture to a blank canvas, I mean as by means of magic, the hand moves free for depictions that flash in my mind [...]. By this wave of song that blandly envelops me, behold the myth rises ancient and new ... in him the magician rises.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.