Néstor Reencontrado shocks any visitor to the Reina Sofía who has a clear understanding of the limits of art. It is not difficult, once you understand that you are not entering an exhibition, but an enveloping and complete atmosphere. Néstor’s fish do not swim, they levitate. Their bodies defy weight and matter. The world that Néstor Martín-Fernández de la Torre (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1887 - 1938) reveals to us does not belong to the categories that art and life strive to trace. Néstor is glamour and mystery, Eros and Thanatos, and the Reina Sofía Museum has the privilege of currently housing a beautifully transfigured reality. His language absorbs modernism, symbolism, Canarian localism, Pre-Raphaelism and many other “isms,” but none of these names encapsulates him: they are simple coordinates that he dissolves in his personal map.

The painter, a proud Palma native and defender of Canarian identity, grew up surrounded by influences that perhaps shaped the direction of his work: perhaps his baritone uncle, who sang in international theaters, showed him the wonders of set design and masks; perhaps his cousin, an island writer, taught him that a work is not complete if all its parts are not coherent; and perhaps it was the love he felt for his architect brother, who designed frames for his pictorial dreams, that pushed him to strive until he achieved exactly what he wanted. From his teenage years, Néstor was inspired by such masters as the portrait and landscape painter Nicolás Massieu, the impressionist Eliseo Meifrén, and the realist and luminist Rafael Hidalgo de Caviedes. At thirteen he was already exhibiting his first works; at fourteen he was studying in Madrid; at seventeen he moved to London and discovered the Pre-Raphaelites and Symbolists. I imagine it was during all these phases-as his early works suggest-that he learned that a body can also be a landscape and that, of course, sometimes a picture is worth a thousand words.

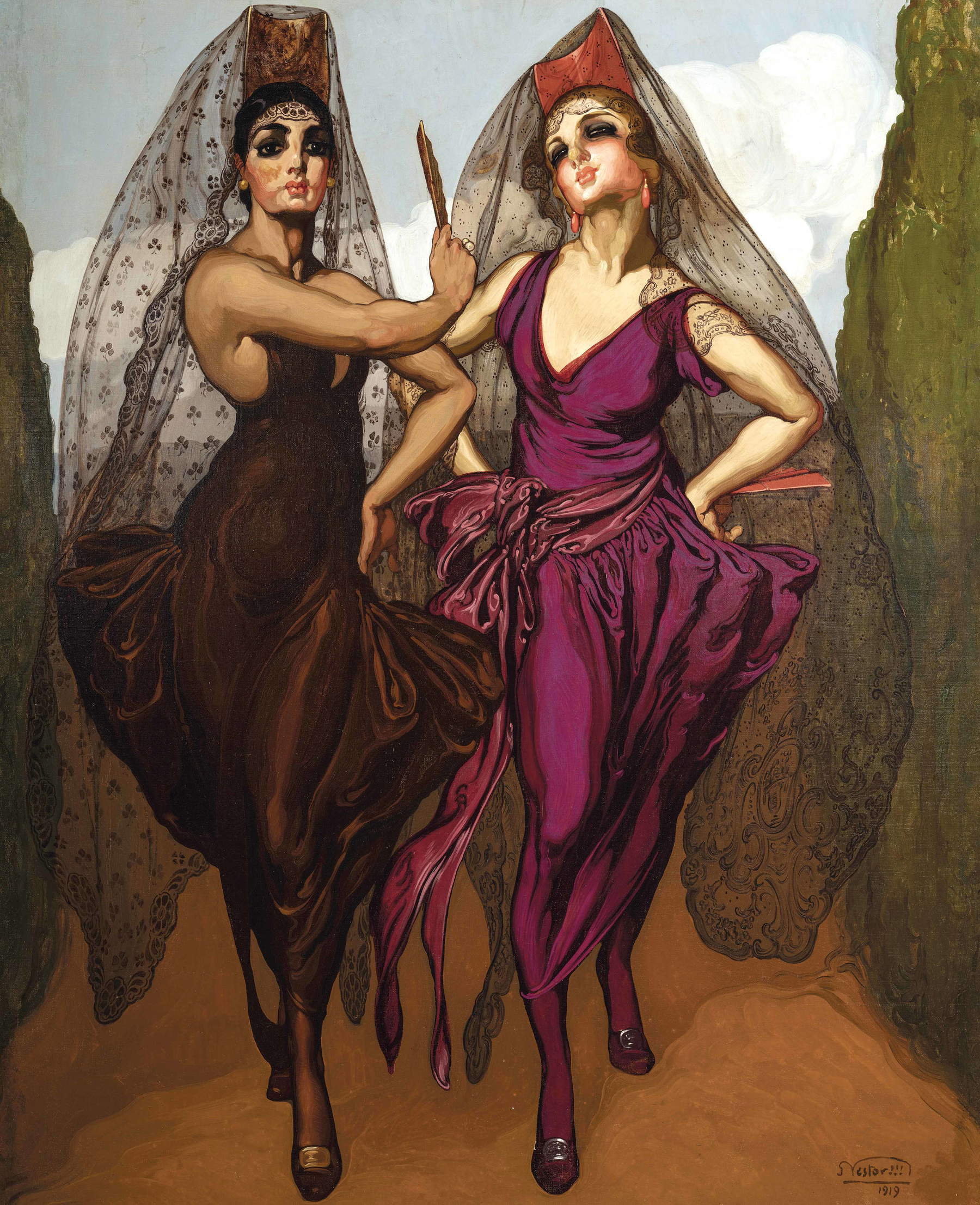

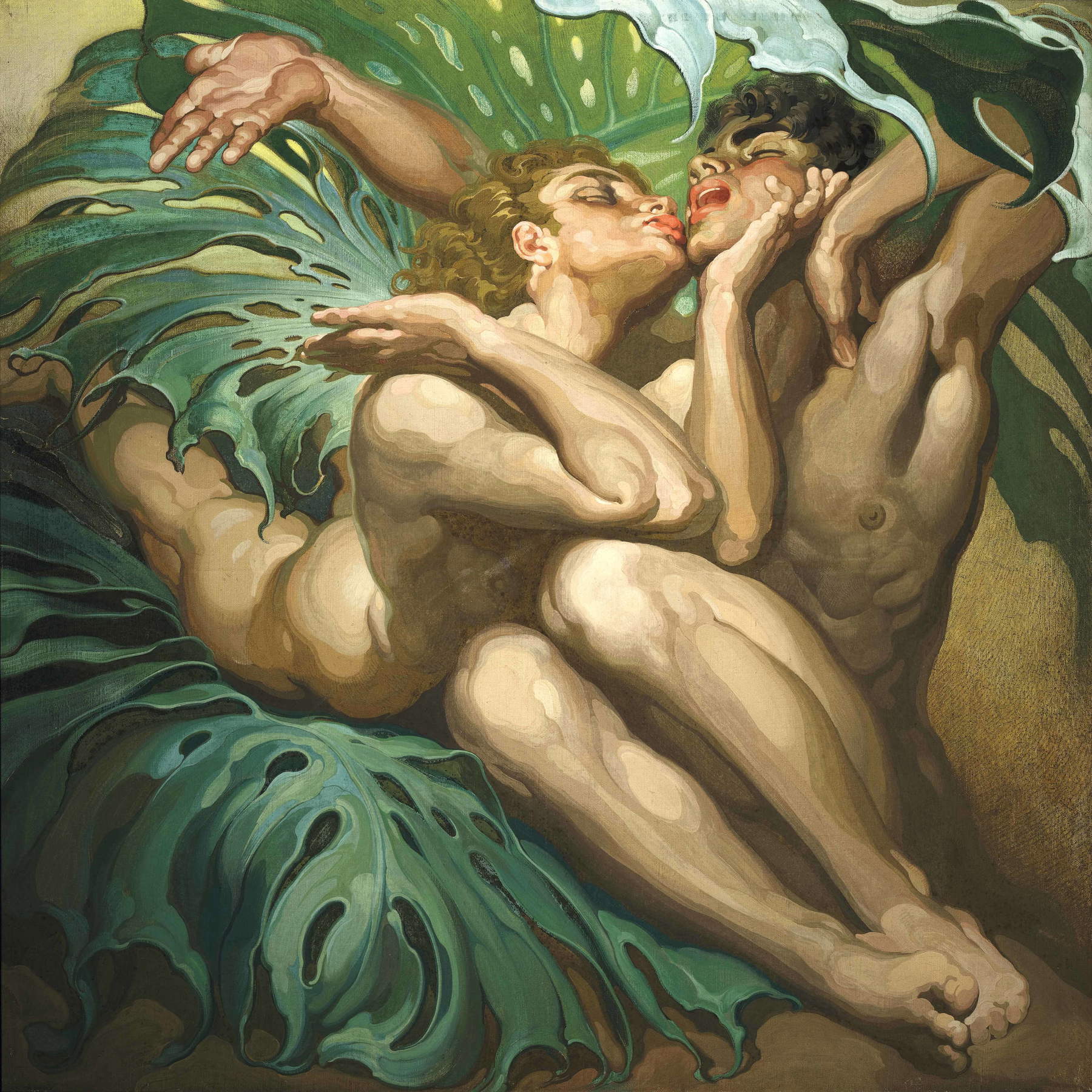

Although it may seem a somewhat strange analogy, walking through Néstor’s exhibition is like listening to a Prince melody painted on canvas: bodies stretched out in impossible poses, open and dilated in an almost unreal way, but delightfully never losing their naturalness. And it would not be surprising if Prince himself, or mangaka Hirohiko Araki, knew Néstor Martín-Fernández de la Torre, for their aesthetics are very similar: the display of exaggerated and theatrical bodies, unafraid to appear sublime or excessive, yet elegant and glamorous. The androgynous figures gaze insolently at the viewer, inciting them to conspire against gender norms that, in reality, should matter no more than the desire for freedom.

In the galleries of the Reina Sofía, Néstor has recovered a nuance of the museums of antiquity: a nuance that, through his works, represents knowledge and prestige, and not a mere invitation to leisure or popular education. For that is what he is in his features: a manifesto on how to live life; an essay on how to look at the world.

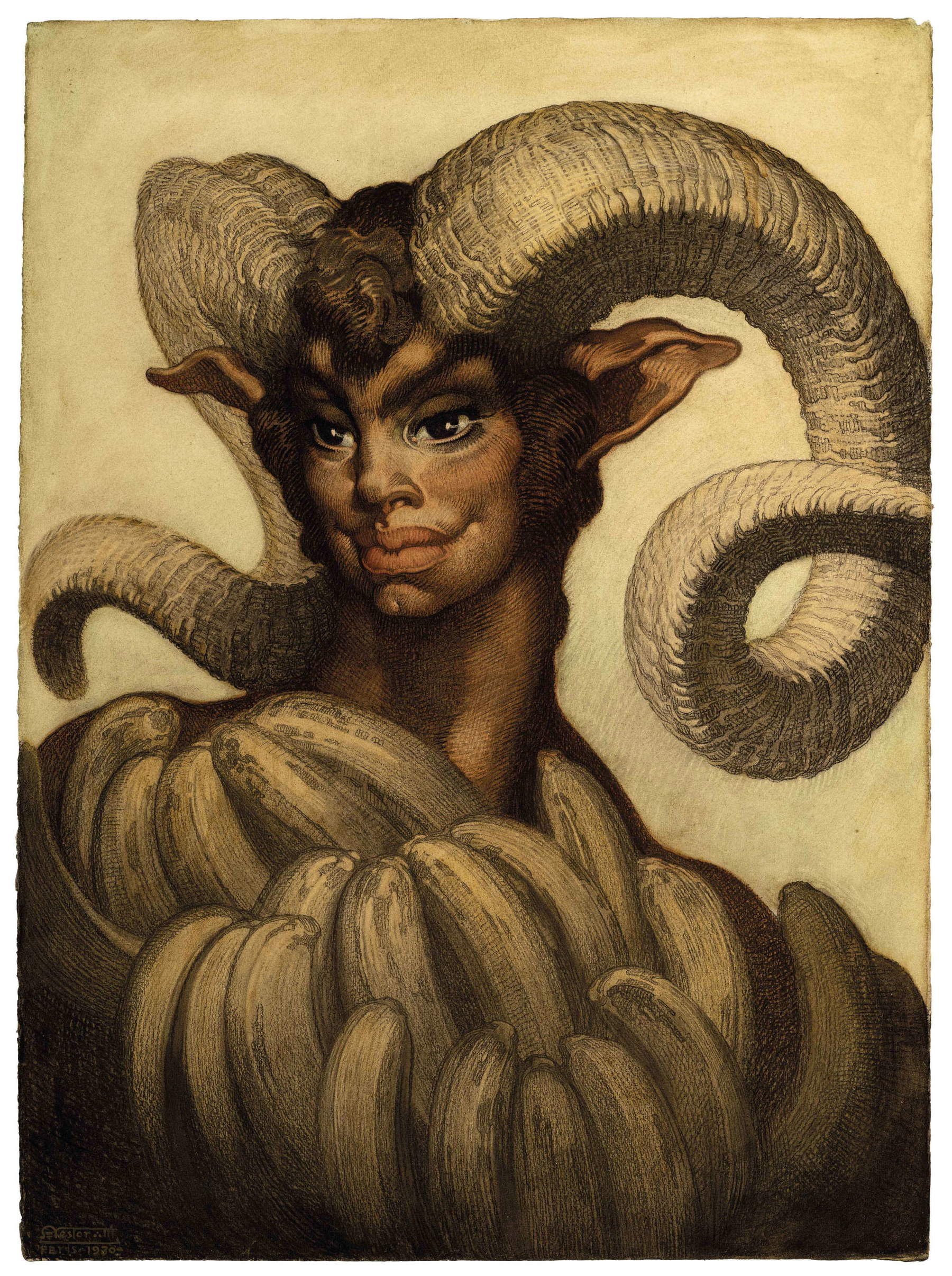

If his drawings were sculptures, they would be carved in marble in the purest Novecento style. But something else emerges in his painting: a Greek epic in the drama of his compositions, a baroque in the twisting of his postures, a Japanese patience for the precision of his strokes, and an expressiveness that seems to vibrate as if oil painting. There are luxuriously charming female faces that could converse with those of Mondigliani’s women, languid and provocative. He knows how to contain himself in a minimal palette when he seeks stillness, and how to unleash an orgy of light when he wants the eye to hesitate at a certain representation. His relationship with Art Nouveau and Art Deco is complex: from the former he takes the sinuous line, stylized vegetation, and floral eroticism; from the latter, the geometry, brilliance, and love of the polished surface. For all these reasons, Néstor’s work cannot be interpreted solely through the lens of modernism or symbolism. It contains a desire for “total opera” that brings it closer to the Wagnerian notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, an art that integrates painting, sculpture, set design, costumes, architecture and even music. If Wagner sought a theater with a miscellany of arts, Néstor embodies it in its visual equivalence. His theatrical sets, costumes, and frescoes reveal a creator who does not need “scenic followers,” to use the words of critic Ángel Vegue y Goldoni, to make an impact: everything in his work has a substantial character.

Critics such as Fabien Sollar and José Francés (whose excerpts can be read at the Reina Sofía), in addition to those already mentioned, confirmed this well-rounded eclecticism in their reviews, pointing out that his art did not rely on external artifices, but emerged fully from the very essence of his vision. The poet Tomás Morales, in his Epístola a Néstor from Book II de Las Rosas de Hércules, called him “the lord of this illusory land,” a nickname that is no embellishment. Néstor was not trying to imitate life, but to redesign it, as great artists do who are not content to reflect the world, but rather reinvent it.

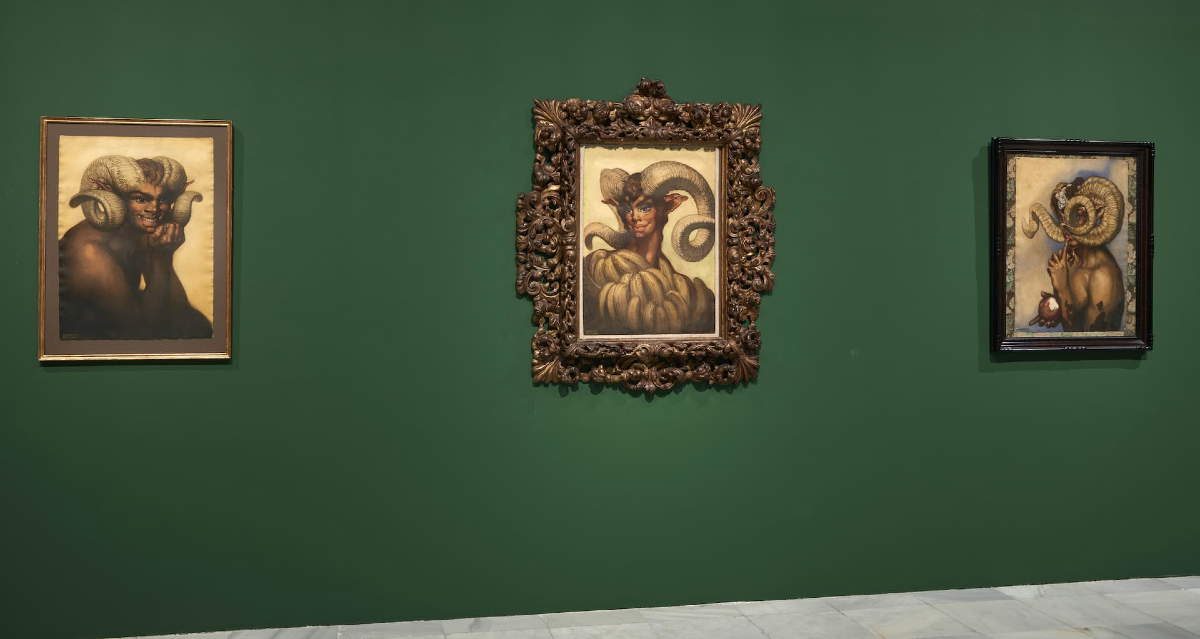

Néstor does not force anything: neither the sets he designed for Manuel de Falla, Gustavo Durán-with whom he had a romantic relationship-or for the dancer Antonia Mercé or La Argentina, nor the sets for the operas, nor the fleshy-lipped satyrs who stare inciting play. The artist also imbues the environment with a mythological nostalgia that envelops a figure in a geometric Art Deco world.

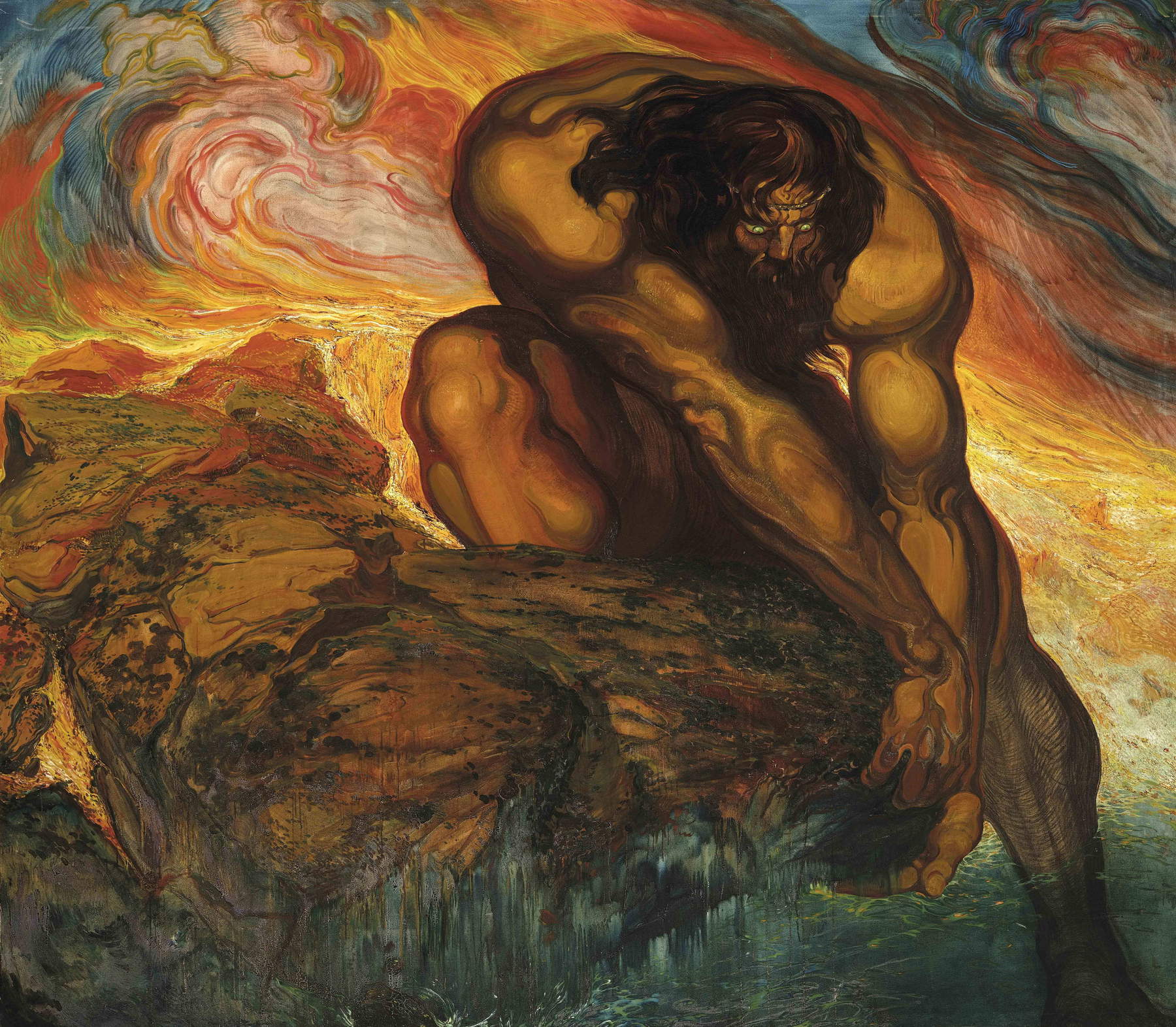

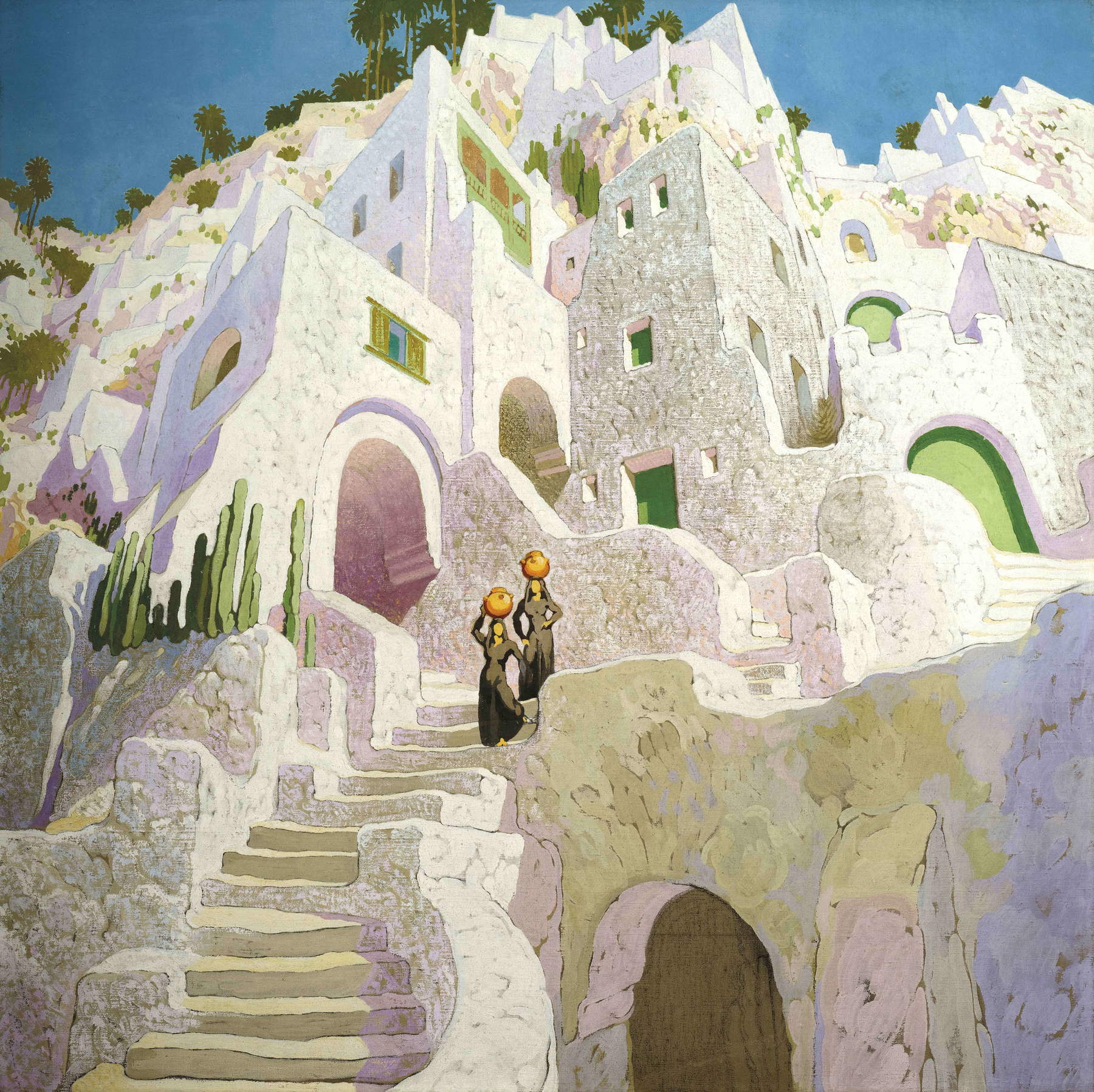

In this personal map, it is worth pausing to consider the coordinates of his Poema del Atlántico and Poema de la Tierra series. Canvases in which fish, bodies and the environment merge into a single breath, harmonizing anatomy and landscape in almost musical rhythms. In these works, water, wind, and flesh are almost interchangeable. His stroke is thoughtful, but never cold: it is the gesture of someone whose gaze slowly breaks down reality in order to analyze it and ends up composing the melody of an entire chromatic carnival.

Néstor introduces a very personal iconographic vocabulary: humanized fish, androgynous figures with almond-shaped eyes, the fusion of anatomy with marine and volcanic elements, as if the bodies were extensions of the earth and the ocean. Here resides something we might call “Atlantic symbolism,” a poetic art in which the sea is not the background but a character, and insularity becomes an aesthetic in its own right.

And the same can be said of his men in feminine poses and the women with male bodies in Poema de la Tierra: in Néstor, from the center of the canvas to the top of the frame, each painting works in complete harmony. At its best, the exhibition succeeds in something that seems increasingly difficult in a museum: making us forget the real map and enter the suggested one. One only has to spend a few minutes in front of a painting in this series to feel how space folds in on itself. Bodies seem to emerge from the sea horizon, hair merges with seaweed, muscles resemble nature’s fresh food. One leaves there convinced that the only way to inhabit the world is to float, to bend, to melt. Androgyny, desire and dreaming are intertwined in an iconography that was once transgressive and marginalized, but is now central to the contemporary artistic agenda. In this sense, his work dialogues with that of other artists obsessed with hybridization: the marine deities of Arnold Böcklin, the fluid bodies of Gustav Klimt or the metamorphoses of Odilon Redon. As a counterpoint, Néstor stands out for the clarity with which he incorporates local imagery into a cosmopolitan language. He is not a “Canarian” painter in the folkloric sense, but rather a universal artist who uses the Canary Islands as a laboratory of forms and symbols.

In fact, Néstor, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, materialized on canvas the bridge between the Canarian folk tradition and the more sophisticated languages of late 20th century Europe. He himself affirmed the character of Canary Island typicality as the most defined among Spanish provinces. Today, elevating this character of island folklore to the status of a universal and enduring symbol throughout history is something only this artist has managed to do. Perhaps the exceptions are César Manrique or Martín Chirino, but time will determine the strength of their influence on the future.

Juan Vicente Aliaga, curator of this exhibition, deserves credit for rescuing Néstor from the dank and foggy history of the Canary Islands to show him not only as the artistic talent that he is, but also as a dissident, perhaps unintentionally, from the moral and aesthetic rigidity of his time. His queer sensibility, his taste for the artificial and his refusal to submit to the dominant realism distanced him from the official manuals, but also gave him a freedom that we can recognize today as revolutionary. The exhibition demonstrates perfectly that Néstor painted as he lived: with the determination of one who does not ask permission to exist.

What I would like to take from the exhibition for this review is Néstor’s awareness that art is not just a mirror, but an ocean that envelops you, overwhelms you, and transforms you. The experience of this retrospective is like a long and deep swim in waters we did not know, but which, once we emerge, we feel as our own. It is therefore a privilege to be able to take the waves of his Atlantic from those somewhat distant shores and place them within the walls of the Reina Sofía, where their murmur mingles with ancient voices-that of Tomás Morales, of critics and friends, his own-and tells us that there is still much to imagine.

And perhaps this is the greatest gift Néstor reencontrado offers us: reminding us that there is a place, as real as it is illusory, where we can be free. A place where Japanese patience coexists with Baroque luxury, where glamour is not an accessory but an attitude toward life, and where painting is not obliged to imitate life because it is, in itself, a life of its own. A place that Néstor built with the precision of a goldsmith and the boldness of a revolutionary, and that now opens its doors to us, allowing us to enter without fear.

The author of this article: Pedro Leóciro Cubría

Pedro Leóciro Cubría si è laureato in Giornalismo e Scienze Umanistiche presso l'Università Carlos III di Madrid. Il suo lavoro come guida presso le Collezioni Reali e la sua passione per l'arte e la storia lo hanno portato a intraprendere una carriera nella gestione culturale e nella critica d'arte e museale.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.