Announced as one of this year’s event-exhibitions and even sold out even before the official opening on September 29, with more than sixty thousand tickets sold (and sold out in advance), the visit to the exhibition Dentro Caravaggio, which Palazzo Reale in Milan dedicates until January 28, 2018 to the art of the great Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio, presupposed no small expectations. The general public has always been attracted to the figure of Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 Port Hercules, 1610), not only because of his undoubted artistic abilities, but also because of his biography that was by no means monotonous, his unruly existence, and his rebellious character-and it is known that the rebellious and damned exudes a charm that can hardly be contrasted with opposing characters.

One expected an exhibition that could compete with what was the most important exhibition dedicated to Caravaggio in the 20th century, namely the one that Roberto Longhi curated in 1951 in the same rooms where this year’s exhibition has been set up. Also because very little information was possessed prior to the dinauguration press conference regarding the choices of paintings to be displayed in the exhibition, as well as regarding the intent of the exhibition.

Inside Caravaggio builds on an extensive study campaign launched on the occasion of the Fourth Centenary of Michelangelo Merisi’s death (1610-2010). The archival research, carried out at the State Archives of Rome, led, in addition to the revision of all documents, to new documentary discoveries that led to a profound revision of the chronology relating to the artist’s early Roman period. But that’s not all: the investigations have also concerned the execution technique that Caravaggio employed in the creation of his works; diagnostic investigations, directed by Rossella Vodret, curator of the current exhibition, in collaboration with the National Committee for the Fourth Centenary of Caravaggio’s death, the Special Superintendence for the Roman Museum Complex and the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro, which began in 2009 and then continued in 2017, thanks to the support of the Bracco Foundation, on the other works on display today at the Royal Palace. These were merged, through a project that saw the University of Milano-Bicocca and CNR working side by side, in a graphic elaboration with the intention of presenting them to the general public in an innovative and more comprehensible way for everyone.

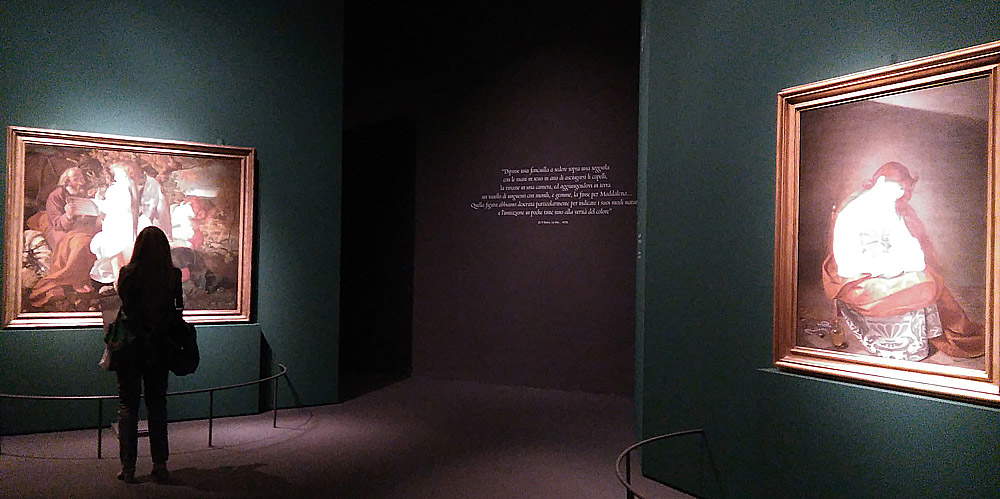

|

| Hall at the exhibition Dentro Caravaggio in Milan |

|

| Hall at the exhibition Inside Caravaggio in Milan |

Behind each panel on which each painting is placed in the exhibition, a short, very high-resolution video is visible that repeatedly projects the results of the radiographic investigations related to the work in question: it will therefore be possible to note any reworkings, modifications, rethinking that led to the final rendering of the painting. A very interesting analysis regarding the history of the creation of each work that allows us to experience step by step the mistakes, the doubts that accompanied the artist in the realization of his masterpieces: almost like immersing ourselves in the mind of Michelangelo Merisi. In fact, Inside Caravaggio title of the exhibition in Milan refers to the great possibility that the exhibition offers to see inside the works of the artist, that is, what is hidden under the surface painting, such as sketched figures, characters shifted to another position on the canvas, details that during the realization of the painting the artist thought of eliminating, as well as the nature and color of the preparation and specific painting techniques that characterized his art.

However, in spite of the attempt to make the diagnostic study of each work more usable and understandable to all, in the opinion of the writer the majority of the public who will visit the exhibition will linger and be enraptured especially in front of Caravaggio’s masterpieces, of extraordinary beauty and considerable emotional impact, but always fascinating for their remarkable narrativity. Predictably, it is to be expected that it will be mainly insiders who will be interested in the videos with diagnostic studies, to whom they are mainly addressed although conceived in pills. Also because it should be noted that a different solution from the point of view of their placement would perhaps have intrigued the general public more. It almost seems as if they wanted to hide the X-ray studies: it is necessary to literally circumnavigate the individual panels to realize the presence of the videos (and we even know of someone who left the exhibition unaware of their existence).

Also with regard to the layout of the rooms in which the visitor will delve into Caravaggio’s art, it has been chosen to use the color black, or at least dark tones, as a common thread for the panels on which the individual works are placed. These stand out against the background and to our eyes thanks to a play of light and shadow that gives importance to each of them: the undisputed protagonist of each panel is in fact each painting. Precisely that chiaroscuro play that placed the figures depicted on the dark preparation in Michelangelo Merisi’s paintings in the foreground.

Pierluigi Cerri, of Studio Cerri & Associati, which was entrusted with the task of setting up the Milan exhibition, said: We have the ambition of having tried here to set up a path of elements organized like a text that allows one to intercept the prodigious work, the exceptional phenomenon or the portentous fact. [ ] This installation designs a path in which a series of volumes are organized into articulated groups in the dimly lit rooms of the Royal Palace, or aligned to allow heterogeneous readings of the works on display. [ ] One topic we dare to address is the abandonment of the tradition of the classical picture gallery, of the neutral white room, in order to adopt color as the background of the works, color pondered by identity or harmonic coincidence with the colors of the images or taken up by stratigraphies that reveal underlying color backgrounds.

Barbara Balestreri, who was in charge of the lighting, adds, Caravaggio is a visionary of light and shadow. The light path developed reflects the artist’s creative process and the way he shaped light in his works. [...]Diffuse halos for the early works give way to sharp silhouettes for the later masterpieces. From canvas to canvas, visitors embark on an increasingly dark journey. An emotional and immersive journey that neither distracts nor alters the power emanating from the works.

|

| One of the videos in the exhibition |

|

| Hall at the Dentro Caravaggio exhibition in Milan |

|

| Sala at the exhibition Inside Caravaggio in Milan |

Ultimately, neither the setting nor the lighting was left to chance: colors, lights and shadows refer to the evolution of Caravaggio’s works. Starting lanalysis of the exhibition itinerary is therefore interesting in order to better understand this link that has been purposely created between works, staging and lighting. First of all, it is necessary to take into account the discovery made by the young scholar Riccardo Gandolfi, presented on March 1, 2017 at the study day Sine ira et studio. For a Chronology of the Young Caravaggio (Summer 1592-Summer 1600). Opinions Compared at La Sapienza in Rome, sponsored by Alessandro Zuccari, Maria Cristina Terzaghi and Sybille Ebert-Schifferer: this is an unpublished manuscript by Gaspare Celio, dated 1614 thus subsequent to Van Mander’s biography of 1604 and preceding Mancini’s Considerations on Painting (ca. 1617-1621) in which we read an articulate biography dedicated to Caravaggio. This writing is important because we can get news about the early years of the artist. It is the first time that explicit mention is made of the reason why the artist allegedly left Milan to move to Rome: it seems that he killed a companion. A confirmation of the datum already written by Mancini in a note to his Marcian manuscript: Fece delitto. Puttana scherzo (?) et gentilhuomo scherzo (?) wounded the gentiluomo et la puttana sfregia sbirri ammazzati volevan saper che i compagni; fu fu prigion un anno et lo volser veder vender il suo [ ] a Milano fu prigion, non confessa, vien a Roma né volse [ ] Fu provocato, andare a casa raccattare a tradimento si misse nel servitio per rispetto suo e in una postilla manoscritta da Bellori alla biografia di Baglione compresa ne Le vite de pittori, scultori et architetti (1642): Macinava li colori in Milano, et apprese a colorire et per haver occiso un suo compagno fuggì dal paese. Continuing to read Celio’s manuscript, which is in the process of being published, we learn about Caravaggio’s economic difficulties in Rome, where he worked for Lorenzo Siciliano painting two heads of saints a day for five baiocchi luna, and the key role Prospero Orsi played in introducing Michelangelo Merisi to Cardinal Del Monte.

The review of documents from theArchivio di Stato di Roma has enabled the acquisition of significant new data that have led to establishing Caravaggio’s first testimony in Rome in March-April 1596, thus changing the chronology of his early Roman years. Until 2010, in fact, it was thought that Caravaggio had arrived in Rome soon after July 1, 1592, the date on which he appears in a notarial deed in Milan, and that after a few years of apprenticeship with Lorenzo Carli, Antiveduto Gramatica and the Cavalier d’Arpino, he had met Cardinal Francesco del Monte around the middle of the decade and finally that all of his youthful works were created between 1592 and 1600, the year in which he had his first public debut in the Contarelli Chapel. It was therefore a matter of bringing back from about 1596 to July 1597, the date on which Caravaggio’s service with Cardinal Del Monte is attested, all the apprenticeships he had done at the workshops already mentioned and the creation of all the works executed before his meeting with the cardinal. And to place the early works from 1596 to 1600.

Let’s start visiting the exhibition: the exhibition itinerary is organized chronologically, according to the new chronology, particularly of the early works, for which the Celio manuscript discovered by Gandolfi was of great help. With one exception: the first room is in fact dedicated to Judith cutting off the head of Holofernes preserved at the Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica Palazzo Barberini in Rome. A work that inevitably arouses a certain sense of the macabre, but unquestionably considered one of Caravaggio’s greatest masterpieces. The painting appears in two wills of Ottavio Costa, a powerful banker from Albenga who fell madly in love with this work, so much so that he forbade his heirs to sell it (he even hid it behind a taffeta curtain). The canvas has been the subject of debate because of its dating: thought for years to date from 1599, as a key moment in the transition between the early works and the realization of the Contarelli Chapel canvases, now thanks to new investigations it is considered appropriate to date it to 1602, since it is similar in compositional structure and also in the techniques used, namely in the pattern of the engravings and in the use of clear sketches, to the Sacrifice of Isaac in the Uffizi Gallery documented in 1603. The Judith in fact, according to Michele Cuppone and Gianni Papi, a theory also accepted and supported by curator Rossella Vodret, would be the painting referred to in a receipt issued by Caravaggio to Ottavio Costa on May 21, 1602; the document discovered by scholar Maria Cristina Terzaghi was believed instead to refer to the Kansas City San Giovanni.

One fact made visible thanks to the x-rays is the presence of two significant pentimenti concerning the distance between the edges of the wound on the neck of the Assyrian general Holofernes inflicted by the young widow from the city of Bethulia, resulting in a shift to the right of the entire head. Lartist therefore chose to depict at the same time both the end of the second slash according to the Bible, Holofernes was struck twice before the beheading, and the action of detaching the head from the body. In addition, Judith’s face probably corresponds to that of the Virgin of the Nativity in Palermo.

The second and third rooms display the paintings that, according to all sources, were made during the period when Caravaggio set up on his own, thanks to the help of Prospero Orsi and the merchant Costantino Spada, and had a room to work in Fantin Petrignani’s palace in April-May 1597: these are the Rest during the Flight into Egypt and the Penitent Magdalene preserved at the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, and the Good Fortune from the Louvre (the version from the Capitoline Museums in Rome is on display). The three canvases were purchased by Girolamo Vittrice, Orsi’s brother-in-law, and after 1650 were sold by Girolamo’s daughter Caterina Vittrice to Olimpia Maidalchini Pamphilj; the Buona Ventura in the Louvre was later sent by Camillo Pamphilj, Olimpia’s son, as a gift to Louis XIV.

Of these, the most interesting from the point of view of both composition and X-ray results is undoubtedly the Rest during the Flight into Egypt: the painting made on a Flanders tablecloth places at the center of the scene the splendid angel with his full figure and long wings while playing the violin, dividing the canvas into two parts. On the left is St. Joseph holding the score, amid darker tones; on the left in full light is the Madonna, who tenderly and sweetly holds the Child to herself. For this composition, it seems that Caravaggio thought of Hercules at the Crossroads by Annibale Carracci, a painter he knew and highly esteemed. From X-rays, in addition to the initial shift to the right of the Angel and toward the center of the Madonna and Child, a nude figure from behind was found in the lower part of the painting; perhaps the position in which the artist had originally thought of depicting the Angel. Displayed next to the Rest is the penitent Magdalene, seated on a chair elegantly attired in a gray-green brocade fabric dress while gathered within herself weeping. The jar with lunguento, pearls and earrings she has given up are depicted in a beautiful still life at the girl’s feet. For the depiction of Magdalene, Caravaggio seems to have used the same model as in the Rest.

|

| Caravaggio, Judith and Holofernes (1602; oil on canvas, 145 x 195 cm; Rome, Gallerie Nazionali dArte Antica di Roma, Palazzo Barberini; Photo by Mauro Coen) |

|

| Caravaggio, Rest during the Flight into Egypt (1597; oil on canvas, 135.5 x 166.5 cm; Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj) |

|

| Caravaggio, Penitent Magdalene (1597; oil on canvas, 122.5 x 98.5 cm; Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj) |

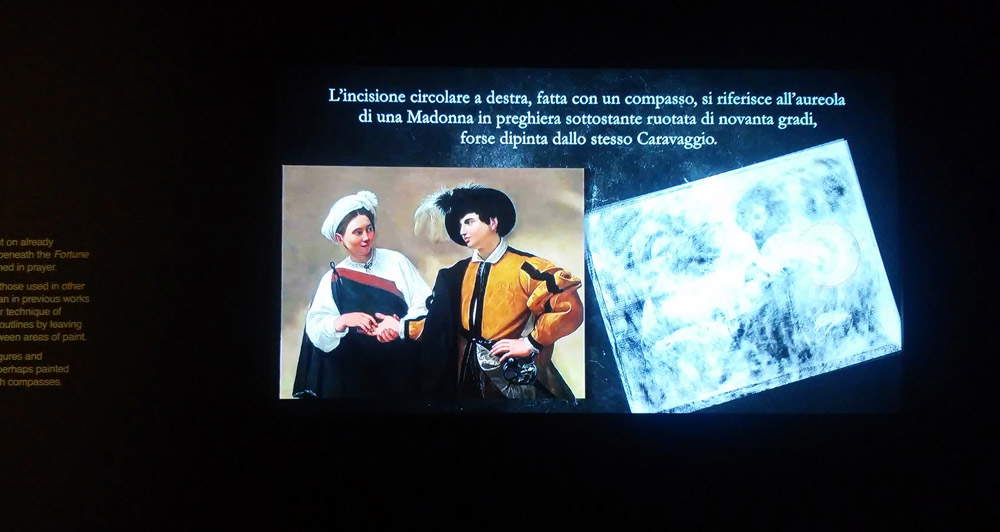

In the next room stands The Good Fortune from the Capitoline Museums, which unlike the one in the Louvre has more mature stylistic features. The work was probably created shortly before his meeting with Cardinal Del Monte, an encounter that changed the young artist’s life: he offered him to become his personal painter and to settle in his home at Palazzo Madama. The viewer’s eye is immediately captured by the movement of the hands, in which one can see, thanks to a recent restoration, the gold ring that the soothsayer is quickly removing from the finger of the young man, who, on the other hand, does not notice anything. X-ray investigations showed that the painting was made using a canvas on which, it was thought, the artist himself would have completed a Virgin and Child Sleeping and that to trace the Virgin’s laureola he used a compass, Caravaggio’s habitual tool but mistaken for a blunt object in a 1598 arrest for illegal possession of weapons.

These works denote some characteristics typical of his early period: the use of a clear preparation on which he draws the characters and objects he intends to depict the Milanese exhibition strongly disproves the assumptions that Caravaggio did not draw using charcoal or dark thin brush strokes, proceeding later with the addition of layers of various colors and the shadows. In La Buona vent ura, the presence of the saving outlines is also noticeable: the pictorial layers of the bordering backgrounds do not come into contact, leaving the preparation exposed.

|

| Caravaggio, The Good Fortune (1597; oil on canvas, 115 x 150 cm; Rome, Musei Capitolini Pinacoteca Capitolina) |

The exhibition continues with the other works attributable to his early period: the famous Ragazzo morso dal ramarro (Boy Bitten by a Green Lizard), before which one is struck by the sensation of movement that emanates from the canvas, caused by the sudden jerk of the green lizard that, coming out of the floral composition, bites the finger of the boy who, from the pain, lets out a scream. The movement is even felt by the shaking of the water inside the vase. This is one of the works for which the artist used a mirror: in the absence of models, he portrayed himself, and a handrest, a tool to stabilize the hand with which he painted. Hartford’s St. Francis in Ecstasy depicts the moment when the saint on the Mount of Verna receives the stigmata: he is supported by an angel with beautiful white drapery in a detailed landscape; in the background are a friar and some shepherds. The saint and the angel are illuminated by a single ray of light coming from the left. Martha and Mary Magdalene, a work preserved in Detroit, in which we see the contrast between Martha, dressed in modest clothing, and her sister Mary Magdalene, in luxurious clothes; the former is intent on converting the latter: a light seems to come from Martha’s hands to reach Magdalene’s face, next to whom a mirror, comb and dung jar, symbols of vanitas, appear, as does the rich dress she is wearing. In these three canvases the preparation begins to get slightly darker than in the Vittrice canvases, reddish-brown in color. Also present are incisions, sparing outlines and light sketchy brushstrokes, features that presuppose a date closer to the Contarelli canvases, made in the 1600s and marking a turning point in Michelangelo Merisi’s artistic activity. A change dictated by the need to hasten the time of execution the canvases of the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi had to be completed in a single year: on the canvas he spread a dark preparation on which he traced the incisions with a sharp instrument and outlined the figures to be represented with broad dark brushstrokes and short light sketch strokes. On the dark preparation that he left exposed, he would add the parts in light or half-light in order to make visible only the figures illuminated by the light, which became the focus of the painting. All around was darkness.

The works in the following rooms therefore continue along this line, highlighting to the viewer the figures depicted who, from the background, seem to push their way to the surface. Flowing before our eyes are the Sacrifice of Isaac from the Uffizi, the Holy Family with St. John from the Metropolitan Museum in New York (a work assigned to Caravaggio but without unanimity), the two examples depicting St. John the Baptist, the one from Kansas City and the one from the Corsini Gallery in Rome, placed side by side, along with the Penitent St. Jerome from the Museu de Monserrat, united by a soft red drapery that partially envelops them and by the same setting in the composition. And again: the Coronationwith Thorns preserved in Vicenza (another work with tormented attributive vicissitudes), the Saint Francis in Meditation from the Civic Museum of Cremona, and the Madonna of the Pilgrims from the Basilica of SantAgostino in Rome. Significant among the discoveries made thanks to X-rays and reflectographs are, in the Sacrifice of Isaac, the presence of a sacrificial coffin in place of the stone on which Isaac now rests his head, immobilized by his father’s hand that is almost about to obey the divine will, and the use for the same painting of ultramarine blue to paint the sky: the precious color denotes the importance of the commissioner, Maffeo Barberini. Also significant are the changes to the St. John the Baptist in the Corsini Gallery: a lamb, typical in the saint’s iconography, is sketched in, and the reed with the cross was previously held with the left hand. We then note changes in the Virgin’s attire in the Holy Family canvas, the red mantle of the Kansas City St. John the Baptist , which originally reached the right edge of the canvas, the addition of the chair and the back of the figure seen with his back to the lower left in the Crowning with Thorns.

|

| Caravaggio, Boy Bitten by a Lizard. |

|

| Caravaggio, Saint Francis in Ecstasy (c. 1598; oil on canvas, 93.9 x 129.5 cm; Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art; Photo by Allen Phillips) |

|

| Caravaggio, Martha and Magdalene (1598-1599; oil and tempera on canvas, 100.2 x 135.4 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

|

| Caravaggio, Sacrifice of Isaac (1603; oil on canvas, 105.5 x 136.3; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Caravaggio, Saint John the Baptist (c. 1604; oil on canvas, 172.72 x 132.08 cm; Kansas City, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; Photo by Jamison Miller) |

|

| Caravaggio, Saint John the Baptist (c. 1604; oil on canvas, 97 x 131 cm; Rome, National Galleries of Ancient Art, Galleria Corsini; Photo by Mauro Coen) |

|

| Caravaggio, St. Francis in Meditation (post 1604, 1606?; oil on canvas, 128 x 90 cm; Cremona; Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone”) |

|

| Caravaggio, Madonna of the Pilgrims (1604-1605; oil on canvas, 260 x 150 cm; Rome, Basilica of SantAgostino; Photo Giuseppe Schiavinotto, Rome) |

From the tenth room there is a further change: the works on display appear increasingly dark and evocative, inducing the viewer to a more meditative attitude. This is because in May 1606 Caravaggio was forced to leave Rome because of the killing in a duel of Ranuccio Tomassoni. From here he began a continuous exile and wandering between various cities that would lead him never to return to Rome. Until 1610, when a pardon for Ranuccio’s lomicide was about to arrive, so he decided to return to the city that had given him honors and glories, but as he embarked, death caught him at Porto Ercole, breaking his dream forever. In the Colonna fiefs, in Palestrina, Paliano or Zagarolo, he made the St. Francis in Meditation (1606), found in a church in Carpineto Romano and now preserved in Palazzo Barberini in Rome. In Naples he completed the Flagellation of Christ (1607), for which a wonderfully evocative setting is reserved in a play of light and shadow that refers to the painting’s greater drama and the suffering of humanity.

In Malta he portrayed the Knight of Malta (1607-1608), now on view at the Palatine Gallery of Palazzo Pitti in Florence, while also in Naples he depicted Salome with the Head of the Baptist, preserved at the National Gallery in London. The dating of the latter work is still doubtful: according to some critics it can be dated to 1607 because of its similarities to the Seven Works of Mercy altarpiece, while Roberto Longhi had it dated to 1610, thus attributable to his second stay in Naples.

The exhibition concludes with the Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610), considered Caravaggio’s last painting, preserved at the Gallerie d’Italia Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano in Naples. Here the figures are outlined only by a few sketchy brushstrokes, and the darkness of the preparation overpowers the light and forms. Investigations have uncovered a figure similar to the one visible today, but smaller in St. Francis in Meditation, the figure of a kneeling Dominican undergirding the executioner in The Flagellation of Christ, and an alteration to the dress of Salome, a work painted on twill canvas.

|

| Caravaggio, Portrait of a Knight of Malta (1607-1608; oil on canvas, 118.5 x 95 cm; Florence, Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Caravaggio, Flagellation (1607; oil on canvas, 266 x 213 cm; Naples, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte) |

|

| Caravaggio, Salome with the Head of the Baptist (1607 or 1610; oil on canvas, 91.5 x 106.7 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Caravaggio, Martyrdom of St. Ursula (1610; oil on canvas, 143 x 180 cm; Naples, Intesa Sanpaolo Collection, Gallerie d’Italia - Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano; Cultural Activities Archive, Intesa Sanpaolo / Photo Luciano Pedicini) |

Inside Caravaggio is accompanied by a catalog that addresses in its essays the theme of the revision of Caravaggio’s early period: Orietta Verdi, thanks to a synthesis of known documents, reconstructs the chronology of the artist’s movements between 1595 and 1597; Francesca Curti traces the geography of the first places he frequented in Rome, taking into account the relationships with the various workshops with which he came into contact, Alessandro Zuccari proposes a possible chronological succession of his early works, Sybille Ebert-Schifferer traces the most significant stages of Caravaggio’s life in the context of his relationships with the personalities he frequented, while Riccardo Gandolfi who illustrates his discovery concerning the Celio manuscript. Also featured are essays dealing with the artist’s execution technique written by Keith Christiansen, Larry Keith and Claudio Falcucci, while an essay by Marco Ciatti, Cecilia Frosini and Roberto Bellucci is devoted to the restoration and research conducted by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure. An e-book attached to the catalog shows the x-rays and reflectographs that are projected from the aforementioned videos in the exhibition itinerary. An exhibition in any case to be visited to see live the magnificent works of the great Michelangelo Merisi and to understand new developments in discoveries related to the artist.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.