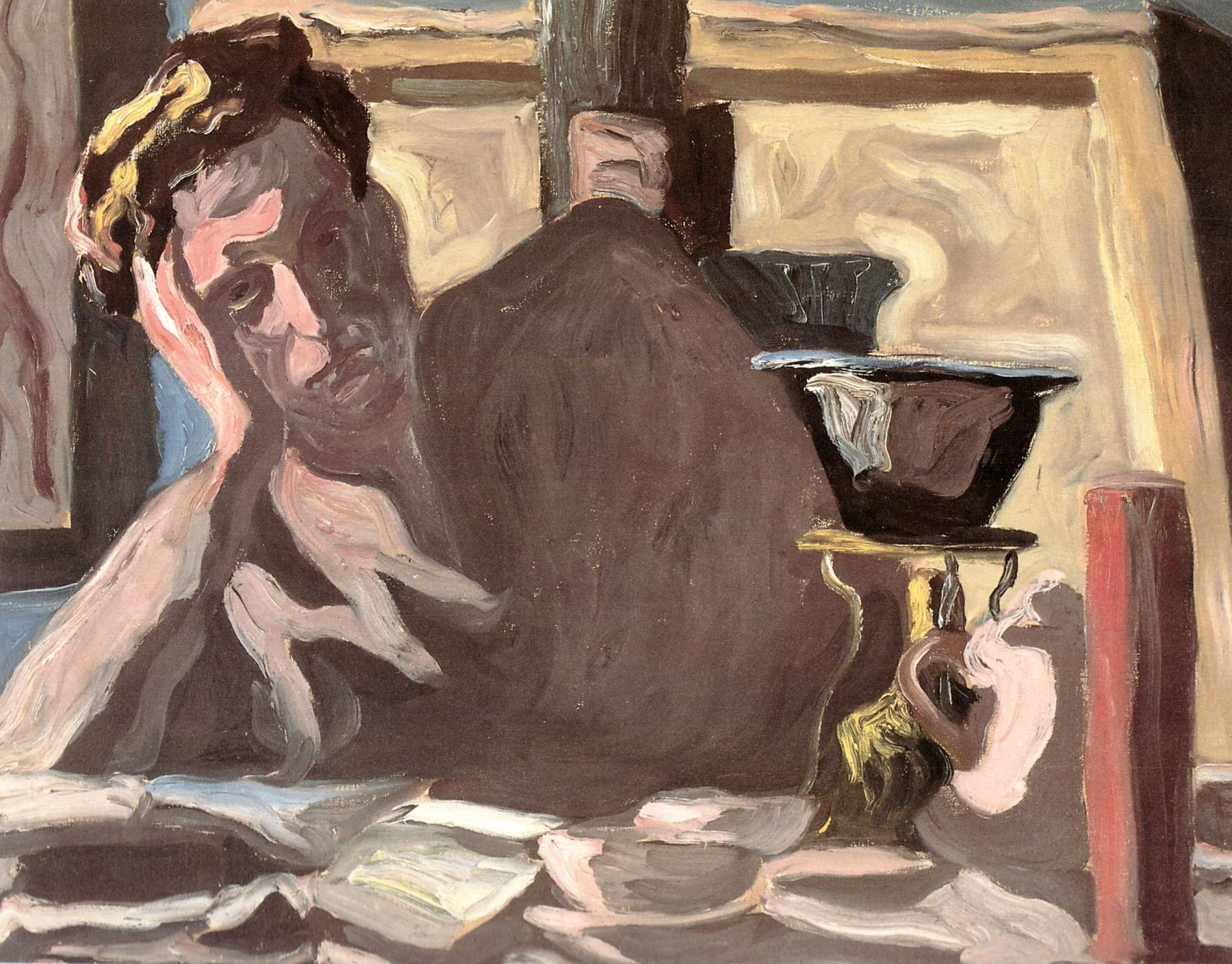

The cigarette elegantly in his right hand and his body slouching against the back of the armchair, on his face a mixed expression of disenchantment and melancholy. Thus, in 1942, Piero Martina portrayed Carlo Levi. Or was it the antifascist painter and writer, who ended up in 1935 in exile in Lucania, which would dictate to him from 1943 the masterpiece Christ Stopped at Eboli (published in 1945), who had his younger friend (one was born in 1912, the other ten years earlier) portray him in this pose? It is, after all, the same armchair-smoking pose with which, also in 1942, Carlo Mollino portrayed-photographed Piero Martina among the furnishings, paintings, plaster models, and still lifes of his (self-taught and with a beginning as a photographer) painter’s studio in Turin. Finally, the last example of this triangulation of portraits and affections, the painting that Carlo Levi executed, still in 1942, immortalizing a brooding Martina with his proverbial “wavy brushstroke” that lingers in his unruly hair, on his crumpled dress and lingers in the monochrome background, but moved like an agitated sea, that invades the foreground inhabited by the young compare.

With the two oil portraits from 1942, the exhibition (open until Sept. 14 at the Gallery of Modern Art in Rome) Homage to Carlo Levi begins. The Friendship with Piero Martina and the Paths of Collecting, curated by Daniela Fonti, Antonella Lavorgna and Antonella Marina (second-born of the painter who died in Turin in 1982), but with the collaboration of Giovanna Caterina De Feo, who was in charge of the section on Levi’s 19 unpublished works from the collection that belonged to Angelina De Lipsis Spallone.

An exhibition, this one in the municipal museum in the former convent of Via Crispi in Rome, that exalts and explains well the work of the two painters from Turin, but both also present and active in Florence and Rome, precisely from the close comparison between their works, although different in poetics and style, and the mirroring of stories, people and loves. Here, in fact, right next to the two portraits of one to the other executed in 1942, is the face of Enrico Paulucci in the melancholy pose (the hand holding up his chin) of Carlo Levi’s 1929 painting when the two, the portrait painter and his model, were militating in that group of the Six of Turin that, under the aegis of Felice Casorati, the drive of the patron Riccardo Gualino, thecritical contribution of Edoardo Persico, with the blessing of Lionello Venturi, looked more to Paris than to Rome, to the European avant-gardes of Impressionist and “fauve” matrix rather than to the autarkic classicism of Sarfatti’s twentieth century-just the underlining of this aspect of cultural politics, and politics tout court, made by Daniela Fonti in the text in the catalog (Silvana editore, 150 pages).

And if in Paulucci’s red ear and purple nose, Carlo Levi registers the linguistic novelties of the “Jewish expressionism” of the various Soutine, Modigliani or Chagall seen in Paris, where he often went and stayed in the mid the 1920s, to the post-impressionism of a Bonnard seems to look, a decade later, the young friend in the painting depicting, in a rarefied and shadowless atmosphere of a foggy Po Valley landscape, The Two Barons (Sartorio): the work is preserved, as are most of his works, in the Martina Archives, which, with the Levi Foundation and the De Lipsis Spallone collection, have lent most of the paintings now on display in Rome.

More faces and stories of painting compared in a diptych-exhibition that, however, does not stop at portraiture, but builds on the face-to-face of landscapes, nudes and still lifes. Here then is Carlo Levi with the Portrait of Carlo Mollino at the Gam in Turin, really a passport photo for incisiveness of the gaze and lack of environmental context, made in oil on canvas in 1938. And, specularly, but 30 years later, the one executed by Piero Martina (the painting is the private collection), making the great architect and photographer from Turin sit in a comfortable armchair and depicting him full-length, while almost erasing his face in a Francis Bacon-esque painterly gesture.

And it is noteworthy that the older painter and great sponsor of his friend (Levi writes for the exhibition d’Martina’s debut exhibition in Genoa in 1938 and then again for the 1951 solo show at the Il Pincio gallery in Rome) maintained from the 1930s to his death (1975) the straight line of an expressionist style that in the postwar period was tinged with southern neo-realism, while the young Piero experimented continuously, welcoming and revisiting the novelties of postwar European art.

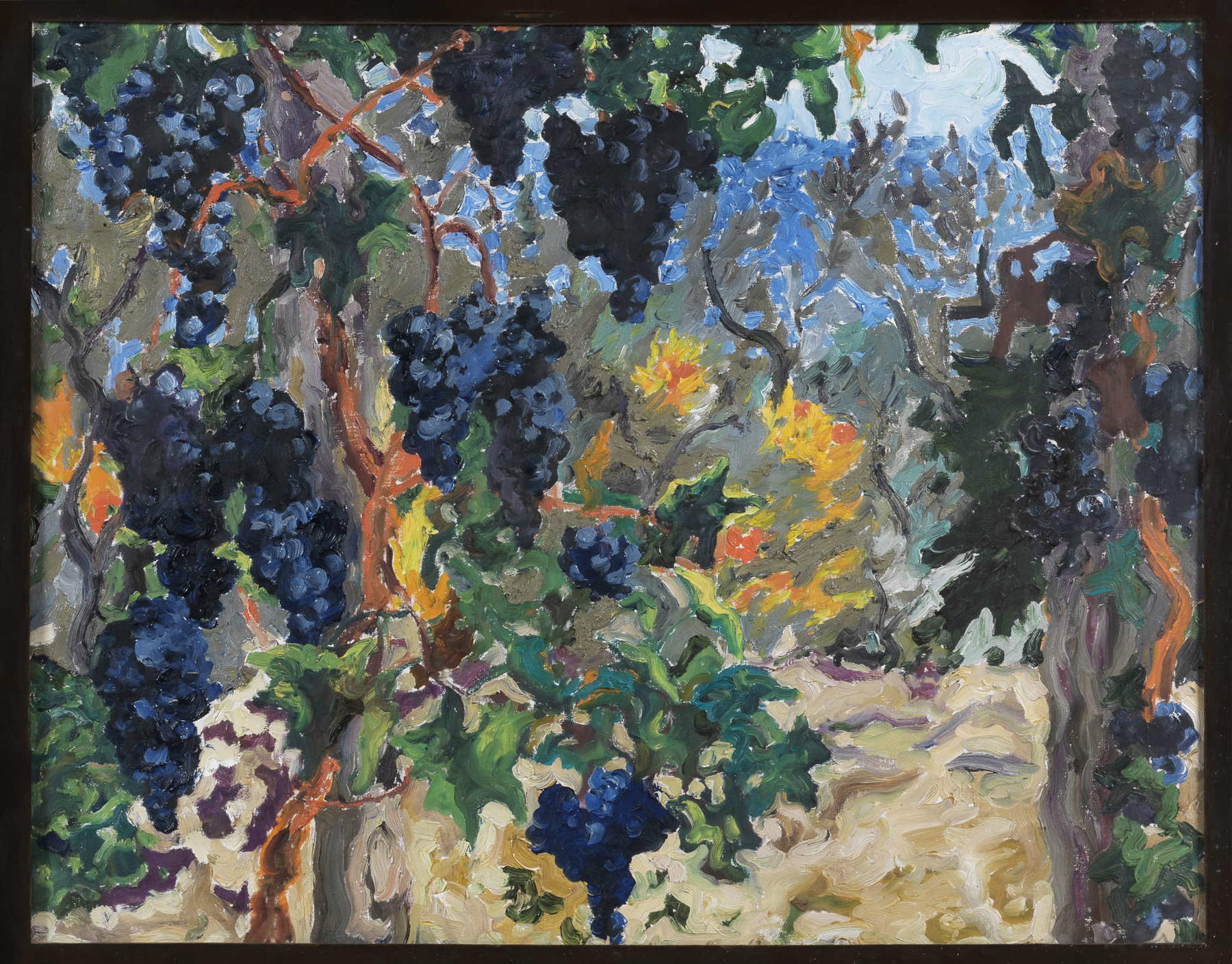

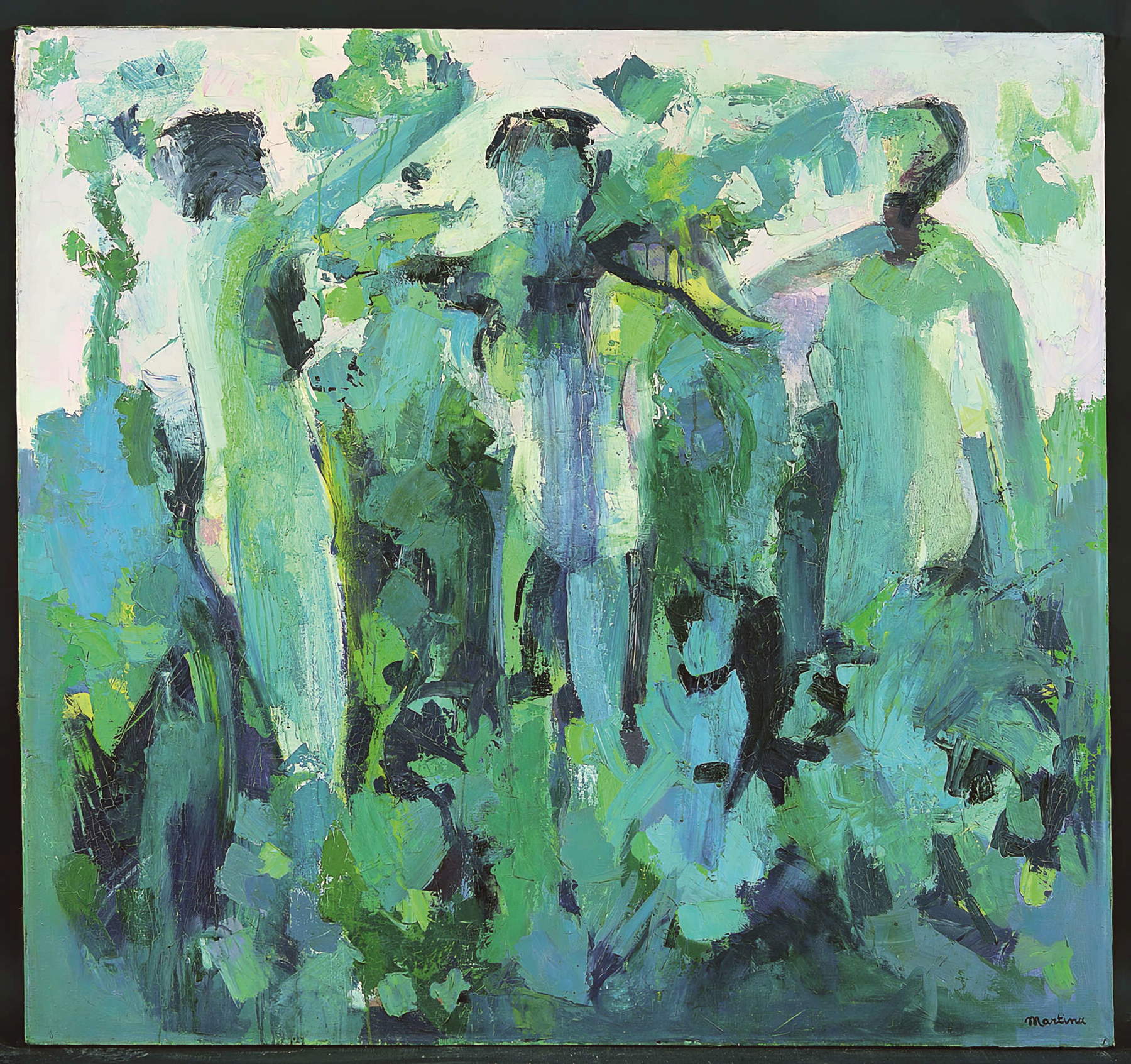

It is enough to look at the landscapes in which Carlo Levi consistently maintained throughout his life, right up to the final carob trees of the Alassio countryside (an exhibition on the “Lost Garden” is open at the Levi Foundation in Via Ancona in Rome), that “wavy brushstroke” recorded in the mid-1930s mostly on dull cream and gray tones after the orgy of “fauve” colors in contact with the Six. Where Martina, in the views of an industrial, wintry, whitewashed Turin, welcomes a broad, textural, decisive doing of the brushstroke that is the opposite of that watery, impressionistic indeterminacy of his 1933 “Corso San Maurizio” (private collection).

Modern and curious Martina was also so in the very active 1950s (from 1948 to 1956 he was present at all five Venice Biennales) when he introduced inserts from synthetic cubism (the real page of a sheet of music and a butterfly wing in the model-musician’s hair) into the collage of Girl at the Harpsichord, a subject treated in 1940 exclusively with a painting of a post-late Impressionist structure.

Another important section, though not always exciting on the pictorial level, of this confrontation between the two “pupils” of the great Felice Casorati (to whom, we remind you, the extensive Milanese anthological exhibition at the Palazzo Reale is dedicated until June 30) is the room of the exhibition reserved for works from the “Season ofcivil commitment,” with the Weaver (Cgil collection) of neo-Cubist implantation that Martina exhibited at the 1952 Venice Biennial, or his 1949 Southern Landscape (Gam, Turin) with a red sun “of the future” splitting the sky of the Apulian countryside, experienced in a - by now indispensable - trip to the South.

On the same plane of political commitment stands Carlo Levi, champion of neorealist southernism, with the intense Ragazzo lucano of 1935, the year of the confinement in Alviano for the Jewish intellectual friend in Turin of the anti-fascist martyr Giorgio Gobetti, compared with the paintings more explicitly inspired by Christ is stopped at Eboli (e.g., 1953’s I fratelli on loan from the Gam in Turin) but also with the 1952 Roman scugnizzo Ragazzo Aleandro to be looked at in parallel with the brats, beggarly and smiling, of starving postwar Rome, immortalized by Richard Avedon’s camera (until May 17, the American reporter’s shots are also on display in the exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery, also on Via Crispi in Rome).

More cross-comparisons in 1942, but on the level of still life: with the melons, pears and onions in Levi’s painting and the roses with shells in one of Martina’s; or, the same year, the former’s Dead Rooster contrasted with the latter’s more innovative Caged Rooster. And then of note, in the gallery of portraits that made Levi famous, theAnna Magnani, his neighbor at the Altieri palace in the 1950s and, from 1941, theEugenio Montale with cigarette in hand.

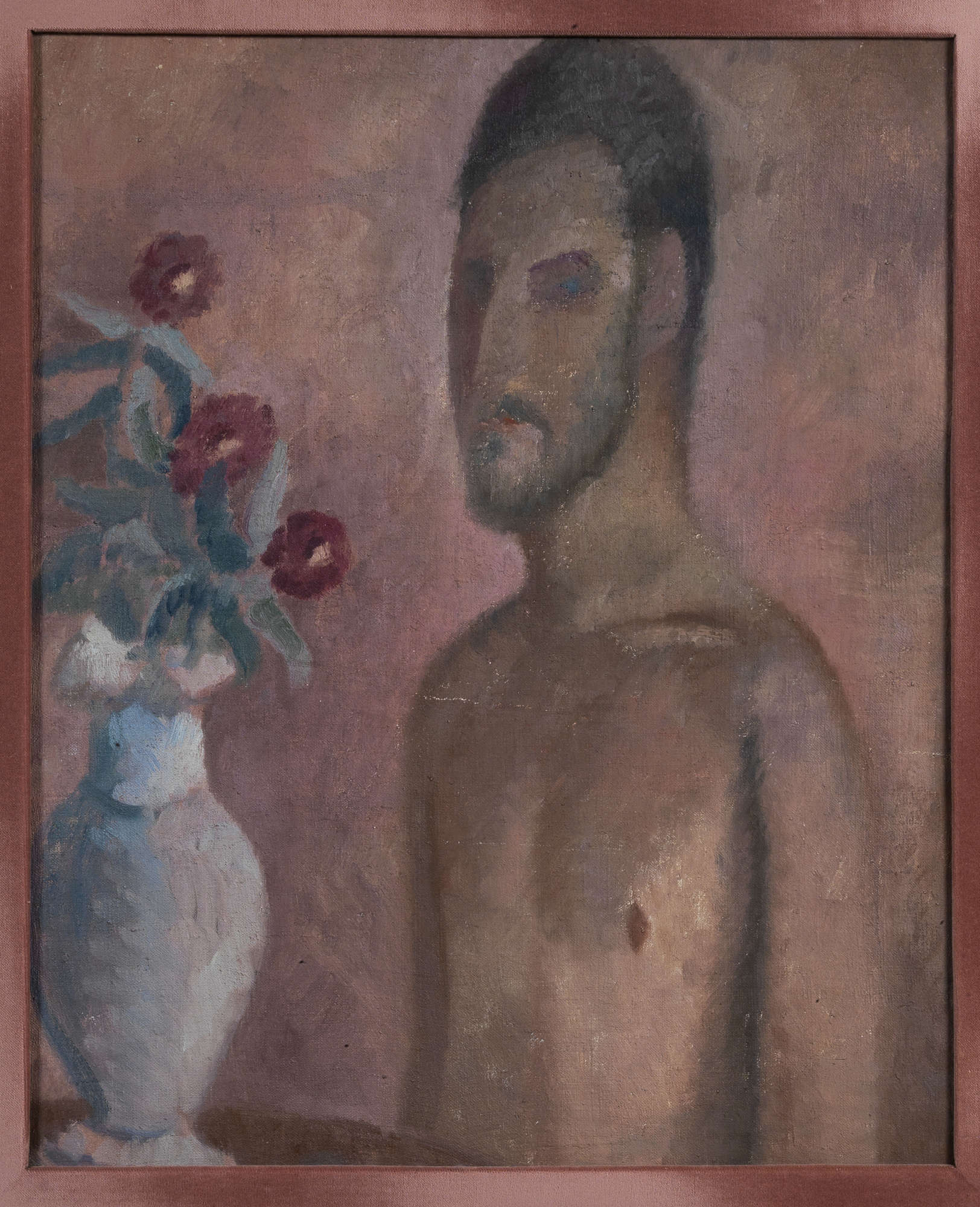

But the parallel race between the common genres and the different approaches of the two painters reaches a peak in the nudes. On one wall we find Levi’s splendid 1928 Nude with Chair (reproduced in the catalog of his farewell anthology, in Mantua, in 1974) compared with the model hiding her face in Martina’s 1940 Seated Nude . And then Levi’s dramatic, colossal and anti-Guttusian, Furious Women of 1934 compared with his younger friend’s now abstract-informal Nudes in the Green Vineyard (1961).

Nude, moreover, Carlo Levi himself appears in the picture of the collection that Angelina De Lipsis, pediatrician and wife of Abruzzi physician Dario Spallone, set up since 1977 by purchasing many of the master’s paintings directly from Linuccia Saba, daughter of the great Trieste poet and companion of the Turin-based painter (and an artist herself) who had died two years earlier. But in this beautifulSelf-Portrait of 1927 Levi depicts himself in pink and half-length, in a therefore demure key; while explicit is the gesture of autoeroticism (on the chaste model, to be clear, of Giorgione’s Venus or Titian’s Venus ) present in his Nudo di donna (Signora Olivetti) of 1939. The curators of the Roman exhibition chose to offer the “verso” of this oil painting, while on the “recto” appears the Portrait of Mrs. Olivetti.

It is still her, Paola Levi, the wife of industrialist Adriano Olivetti, who appears, however, dressed in a suit and wearing a black hat adorned with a floral bouquet on her head. In a single canvas, in short, two versions for the effigy of the beloved woman: the official one that depicts her erect, elegant, stately; and, the other, private and intimate, of the nude lying in a veiled gesture of autoeroticism, while with the other hand the model covers her face.

The author of this article: Carlo Alberto Bucci

Nato a Roma nel 1962, Carlo Alberto Bucci si è laureato nel 1989 alla Sapienza con Augusto Gentili. Dalla tesi, dedicata all’opera di “Bartolomeo Montagna per la chiesa di San Bartolomeo a Vicenza”, sono stati estratti i saggi sulla “Pala Porto” e sulla “Presentazione al Tempio”, pubblicati da “Venezia ‘500”, rispettivamente, nel 1991 e nel 1993. È stato redattore a contratto del Dizionario biografico degli italiani dell’Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana, per il quale ha redatto alcune voci occupandosi dell’assegnazione e della revisione di quelle degli artisti. Ha lavorato alla schedatura dell’opera di Francesco Di Cocco con Enrico Crispolti, accanto al quale ha lavorato, tra l’altro, alla grande antologica romana del 1992 su Enrico Prampolini. Nel 2000 è stato assunto come redattore del sito Kataweb Arte, diretto da Paolo Vagheggi, quindi nel 2002 è passato al quotidiano La Repubblica dove è rimasto fino al 2024 lavorando per l’Ufficio centrale, per la Cronaca di Roma e per quella nazionale con la qualifica di capo servizio. Ha scritto numerosi articoli e recensioni per gli inserti “Robinson” e “il Venerdì” del quotidiano fondato da Eugenio Scalfari. Si occupa di critica e di divulgazione dell’arte, in particolare moderna e contemporanea (nella foto del 2024 di Dino Ignani è stato ritratto davanti a un dipinto di Giuseppe Modica).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.