The curators of the Felice Casorati exhibition at Palazzo Reale, through June 29, are the same ones who followed the edition of the Piedmontese artist’s general catalog 30 years ago: Giorgina Bertolino and Francesco Poli. They are joined by Fernando Mazzocca, who in retracing Casorati’s critical fortunes forgets Edoardo Persico, who instead knew the artist well, even assigning him a role in the development of the Six of Turin group (essay in “Le Arti Plastiche” summer 1929) held as a baptism by the Neapolitan critic when he found himself in the Piedmontese capital, where he had landed in 1927 after trying to collaborate more closely with Piero Gobetti (who had died in the meantime) and suffering the hardships of a life scarce in remuneration and satisfaction (he worked as a cleaning man at Fiat), despite having the esteem of figures such as Lionello Venturi, whom he had met thanks to Mario Soldati’s mother who also helped him by arranging for him to be hired as an editor by the magazine “Motor Italia.” Moving to Milan in 1929 and beginning to work for “Casabella” alongside Giuseppe Pagano, who was its editor, Persico was the first, I believe, to emphasize Casorati’s contribution to Italian decorative arts and architecture, the same - he wrote - that Picasso and Léger did abroad. In “L’Italia letteraria” in 1934 Persico emphasized precisely “the contribution that Casorati and Chessa made to the formation of Italian rationalism: one with the theater of Casa Gualino, the other with the pavilion of the Artisans’ Community of Photographers at the Turin exhibition in 1928.”

The critic had met again with Casorati in Milan to talk about an exhibition that was to be held in November 1934 in Turin, which did not take place for various reasons, including the hostility of some (“a city where everyone lives as enemies”). The exhibition was replaced by the lecture that is now considered one of Persico’s seminal texts, Profezia dell’architettura, held in Turin on January 21, 1935, which was initially supposed to be titled Dalla parte dell’Europa. Alfonso Gatto, in 1945, recalled the emotion of that evening: “His words opened spaces, elevated countries and architecture, released the happy and vital air of the tinting of the great Impressionists... ” A relationship, the one with Casorati, that had already lasted for a few years, since 1928 when the critic founded Edoardo Persico’s La Biblioteca Italiana, publisher of only one book, the re-edition of Prezzolini’s Sarto spirituale; the second, already ready for the printer, was to be Lionello Venturi’s Pretesti di critica, which did not see the light of day, later coming out from Hoepli; while a monograph on Casorati was also announced, but never published. Everything burned almost in a flash, including Persico’s dreams of publishing.

Pointing out that Persico was not a casual acquaintance for Casorati, but one of the critics who first sensed his greatness, going into the merits of the Milan exhibition, visiting it I felt a strange sense of catatonia, I think due to a set-up devoid of internal tension and by “gray” lighting, which has the singular effect of making Casorati’s paintings look better in photographs than from life. Yet, if there is a painter who knows how to get from color that internal drive that projects the painting into an unreal and metaphysical space this is Casorati himself. It is not by chance that he is considered a protagonist and inspirer of that painting that passes under the name of “Magic Realism.”

The first to use this definition was in 1925 the critic Franz Roh, but it would be Massimo Bontempelli in 1927 who would make it a kind of “movement” within the arts and literature of the time, a different feeling from the early metaphysics of De Chirico, Carrà, Savinio, Morandi, de Pisis, of Sironi and Martini; but, above all, far from the De Chirico that was born from a kind of congestion of reality, a crystallization or an immanentism of forms; where the closed forms, even when prisoners of a dream, are a manifestation of the nihilism that seals everything under a resin hardening and fossilizing the appearance of the world giving it a semblance of eternity hic et nunc, but with an explicit attraction to everything that leads to nothingness and the deadly thought of reality, almost a museum of ruins.

Magic Realism emerges from the swamps of the post-avant-garde by adhering to a “call to order” that is primarily a return to the transfiguring force of reality. On Casorati will always act the perennial enchantment for Klimt’s painting. But if we want to give it theoretical depth, then it must be said that, on the level of ideas, that realism stops time and the world within an epochè, phenomenologists would say, that tests its durability without reducing everything to stasis; it is magical because it revives what would be, in itself, “the object of stillness...”

After half a century of no longer being talked about, it was at the Galleria dello Scudo in Verona that in 1988 Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco exhumed the evidence of Magic Realism, showing its expressive power. The return to painting in the 1980s and 1990s also restored lifeblood to Magic Realism by increasing its possibilities on the market. The sudden breakthrough that would drive Magic Realism back into the silence from which Jean Clair had redeemed it with the exhibition Les Realismes at the Pompidou was still far off. That exhibition, which opened just before Christmas 1980, was the baptismal act of the “return to painting.” But, behold, twenty years later, the traumatic reversal of the scene produced by the 2001 Twin Towers bombing inhibited so much positive energy in pictorial and sculptural research, opening thehorizon to a type of art that found in the desperate performances of the financial world its only aura,constrained to a response that corresponds to the devious logics of the real estate that has transformed the world into a unique and demented aesthetic lunapark, the parameters of which are those identified by Rem Koolhaas for the architecture of the end of the millennium: Bigness and Junk space. Magic Realism had fallen back into a kind of hibernation from which at the end of 2021 Gabriella Belli and Vario Terraroli tried to awaken at least its suggestive power. The problem, in my opinion, was precisely that that exhibition repurposed the discourse by reducing that experience of the 1920s and 1930s to its enchanting effect. The fact is that there is nothing in the history of twentieth-century Italian art that resonates more than Magic Realism as an evocative slogan but, essentially, lacking in theoretical hold.

In any case, even in 2021 the curators included Casorati among the standard heads of that poetics, alongside Cagnaccio di San Pietro and Antonio Donghi. Skipping all critical passages, one could say that a bit of Magic Realism between the 1920s and the 1930s can be found if not in all, certainly in a good part of the most prominent figurative authors in Italy in an’epoch full of inner conflicts but substantially moved by sentiments that in the thought of the classic found their peace and made the “call to order” not a totalitarian will, but the only way out of the irredeeming shattering that the avant-gardes left with their attempt at tabula rasa.

What Magical Realism is, then, even now is not clear to me except as a broad and articulate transcendent feeling seasoned with tradition and classicism, merging plastic values and the geometries of space, themes that the avant-gardes and a certain positivism had denied to artistic discourse. Picasso’s Mediterranean metaphysics is an eventual term of comparison, as is the already post-metaphysical De Chirico, but everything stands only on the critical value intended to be given to that expression. At the time, I had the impression that in order to theorize this oxymoron, an attempt was made to explain the adjective (magical) with such perseverance that it became the real noun, as a synonym summarizing classicism, metaphysics, archaism, Mediterraneanism, dream vision, mysticism of the body, inner light, etc. A few years before Belli and Terraroli’s exhibition, Renata Colorni had retranslated Thomas Mann’s unfinished masterpiece, changing the title to The Magic Mountain after decades in which it had held up to a translation perhaps less faithful to German vocabulary but more pregnant, The Enchanted Mountain, where under this title still acted the Freudian Das Unheimliche consciousness, the uncanny that brings out the frightening shadows entrenched behind deep family legacies. We can think, turning the tables, that that Magic Realism, which sounds in this case much better than the new name christening in Enchanted Realism could, under the skin of classicism, reread through the things that show themselves in all their perfidious and bewitching fullness of form, beyond the turgid clarity of the compositional frameworks, in which Casorati is a master, here, can we unveil or present a degree of terror governed only through the stillness of the transfigured real?

Soffici also spoke of “synthetic realism” (1928). And this broadens the field to a variety of styles and experiences that counter positivism as much as materialism, scientism, that is, rationalism, generating a kind of “enchantment” that brings back into play the same psychoanalytic work that in the 1930s might already have been a harbinger of Europe’s coming apocalypse. But the game was perhaps not worth the candle if De Chirico saw in it the “things shining with an inner light” and Bontempelli, evoking Dante, a “prophecy of things to come.” The prophecy of tomorrow had little to do with the “substance of things hoped for” with which Persico concluded his lecture. Or rather, if it was to be so, it was better not to provoke the gods and their nemesis.

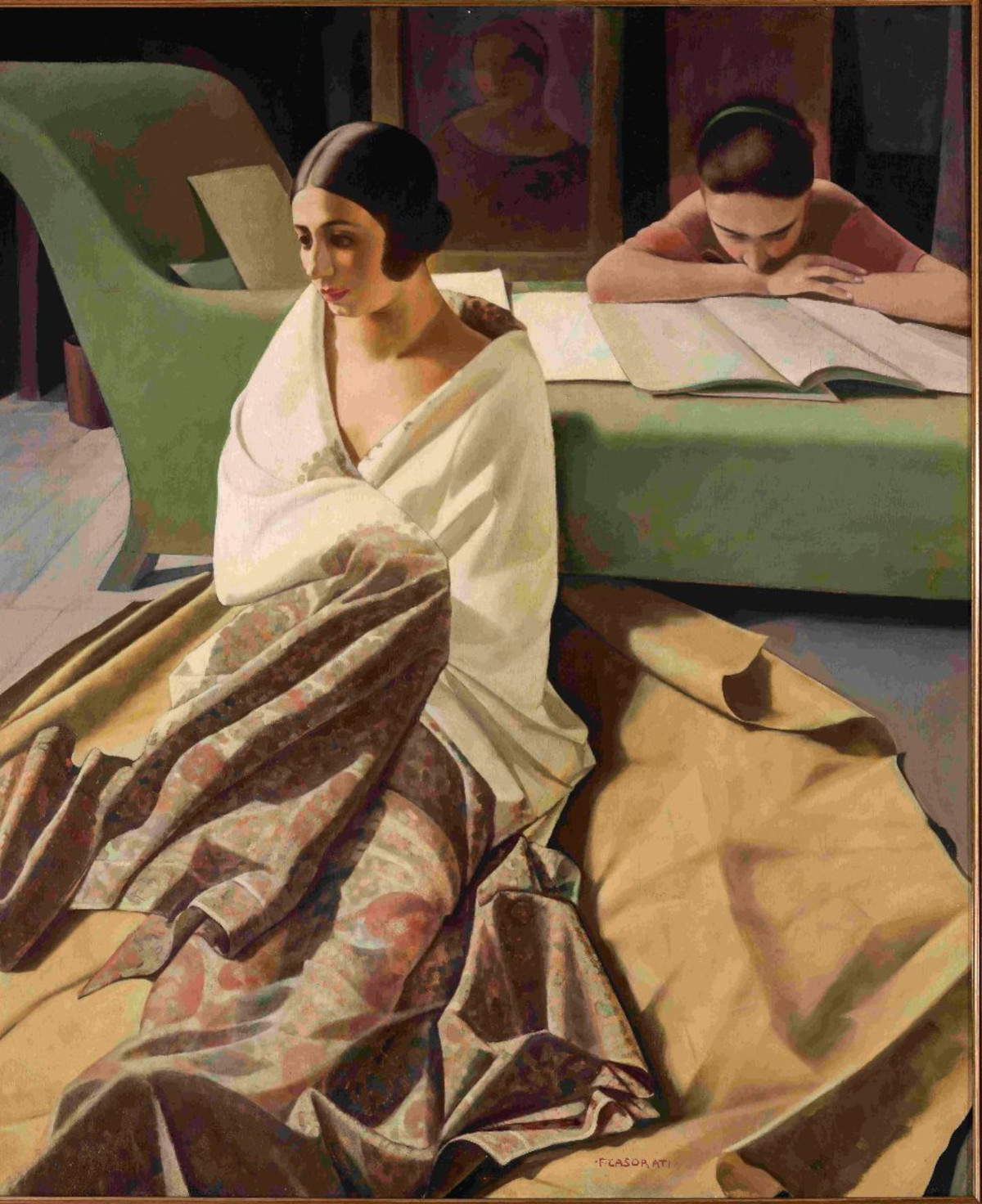

False start, because Magic Realism remains a “critical chimera” - it is not a movement, so to speak, at most, it is an air, an atmosphere of sensibility, of taste so to speak -, where appearance covers deep truth: the poetic distance between Felice Casorati and Cagnaccio di San Pietro, makes them irreconcilable beyond a simple phenomenological approach: the metaphysical and neo-Renaissance dream of the former has nothing to do with the “theater of cruelty” of the latter. With all good will, it will be difficult to see any relation between the anti-bourgeois disgust to which Cagnaccio in 1928 gives form in After the Orgy with the venomous hyperrealism that reduces women’s bodies to objects of use for males shaped by theuse for males shaped by Fascist virilism (which he vituperated); and the metaphysical seduction of the bourgeois gynoecium in such Casorati paintings as Le signorine (1912), L’Attesa (1919), La donna e l’armatura (1921), Raja (1924), Meriggio (1923), Concerto (1924). Not to mention the Platonic Conversation where Casorati’s intention is very far from the impulse, anger if you will, of the moralizing and anarchic Cagnaccio. The seduction of form is for Casorati something that descends from the feminine matrix of his thought on painting, so much so that one could find its shadow in something very distant from the mulieval forms, but substantially close in the essence of perfection, the grace concealed in the feminine, such as the still lifes that have eggs as their subject, chosen as a tribute to the Pierfrancesco inspiration, but in reality also in the painting of the great Tuscan linked to an idea of perfection that is reflected in the discourse on the feminine.

Casorati’s style remains intact over the decades, albeit with many internal variations: he cloaks himself in Symbolist elegances, engraves forms with a scalpel that enhances the sense of the archaic, the “non-eloquent” thought of the Turin years, and arrives at the diamantine form of the portrait of Silvana Cenni (1922); after the meeting with Riccardo Gualino, who commissions him to paint family portraits, including that of his son Renato, which expresses a particular feeling of the androgynous in the theme of ’infancy, here Casorati arrives at that feeling of form where magic and enchantment are two forces that make his painting a manifestation of the contrast between Apollonian and Dionysian, not surprisingly followed in the 1930s by a sense of melancholy, but with a return to the woodiness of forms that abandon the fullness of light exploded in the paintings of the 1920s, to rediscover the archaism of the early Turin period. Then the voracious metamorphosis of Picasso also acts on him, which Casorati reinterprets in works such as Woman with Mantle (1935), Green Nude (1941), Two Women (1944).

Our artist did not like to theorize about painting, notes Mazzocca in the introductory essay of the catalog published by Marsilio arte. The artist declared himself indifferent to “noisy fashionable theories” as he would say in a lecture in 1943, when his name already belongs to the history of the masters of the first half of the twentieth century. Again Mazzocca, who is now also among the curators of the Forlì exhibition dedicated to Self-Portrait, cites Casorati’s declaration of “extraneousness” with respect to the figures he portrays: “I have never painted a self-portrait and it does not seem to me that the figures in my paintings resemble me.” The critic’s comment is also a contradiction in terms: “The author is therefore not present in the work, from which he declares his extraneousness.” We know that this cannot be true: the author, as in novels, is always the mask of the writer who hides there so that he can be free to say without being taken literally (or so he would like, but the parlor game generates precisely this investigation of the reader in search of the truth quotient and on the possible lie, declared, of the writer who offers us instead the verisimilitude). An artist’s ego has many faces. The moment the painter says he never portrayed himself, what is he confessing?

He was also considered a “lonely” artist. In his youth, during his years in Naples, between 1907 and 1910, he lived like a bear. His story seems to be reflected in Bruegel’s painting of the Parable of the Blind. At Capodimonte he is assiduous in his study of the old masters. These are years where, however, although he is still quite young, he participates in the Venice Biennale. He is not an academy graduate and has a mindset that while he does not follow academic paths, nevertheless he never separates himself from the lessons of the classics. Mazzocca speaks, about the 1909 painting The Old Women, of “naturalism and inner tension.” The truth then what could it be? If we were to turn the painter’s statement upside down, it would follow that his entire oeuvre is a single, ineffable self-portrait that lies behind the painting’s forms, lights, colors and, above all, composition.

The author of this article: Maurizio Cecchetti

Maurizio Cecchetti è nato a Cesena il 13 ottobre 1960. Critico d'arte, scrittore ed editore. Per molti anni è stato critico d'arte del quotidiano "Avvenire". Ora collabora con "Tuttolibri" della "Stampa". Tra i suoi libri si ricordano: Edgar Degas. La vita e l'opera (1998), Le valigie di Ingres (2003), I cerchi delle betulle (2007). Tra i suoi libri recenti: Pedinamenti. Esercizi di critica d'arte (2018), Fuori servizio. Note per la manutenzione di Marcel Duchamp (2019) e Gli anni di Fancello. Una meteora nell'arte italiana tra le due guerre (2023).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.